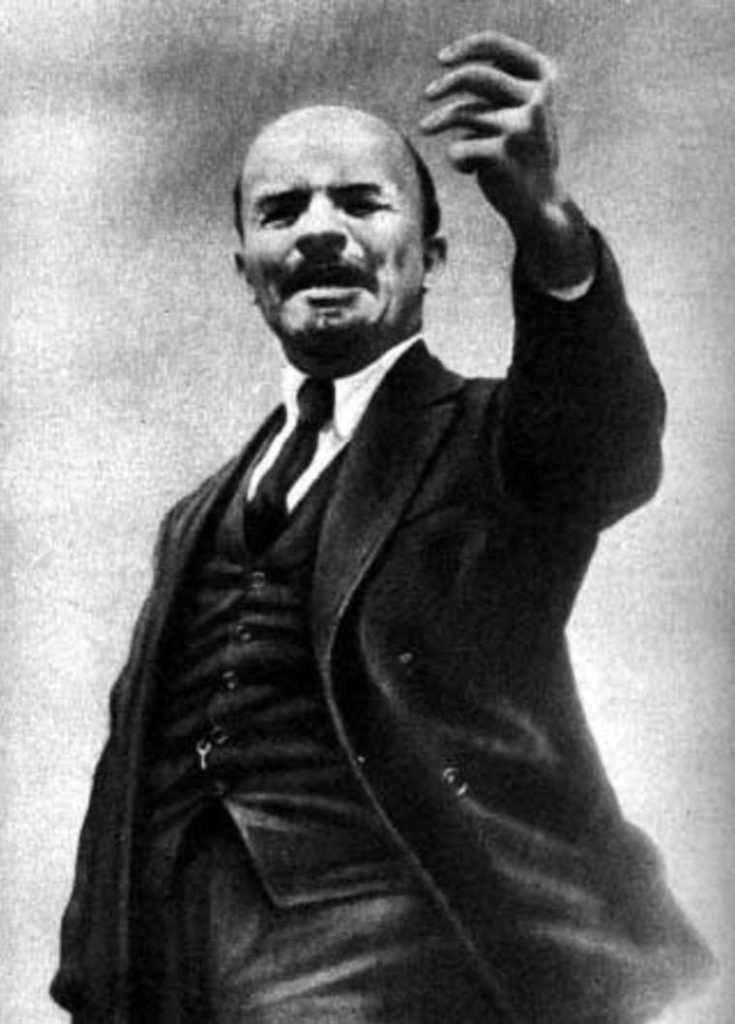

Lenin today

Chris Cutrone

Platypus Review 126 | May 2020

Presented at a Platypus teach-in on the 150th anniversary of Lenin’s birth, April 22, 2020. Video recording available online at: <https://youtu.be/01z8Mzz2IY4>.

ON THE OCCASION OF THE 150TH ANNIVERSARY OF LENIN’S BIRTH, I would like to approach Lenin’s meaning today by critically examining an essay written by the liberal political philosopher Ralph Miliband on the occasion of Lenin’s 100th birthday in 1970[1] — which was the year of my own birth.

The reason for using Miliband’s essay to frame my discussion of Lenin’s legacy is that the DSA Democratic Socialists of America magazine Jacobin republished Miliband, who is perhaps their most important theoretical inspiration, in 2018 as a belated treatment of the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution of 1917 — or perhaps as a way of marking the centenary of the ill-fated German Revolution of 1918, which failed as a socialist revolution but is usually regarded as a successful democratic revolution, issuing in the Weimar Republic under the leadership of the Social-Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). There is a wound in the apparent conflict between the desiderata of socialism and democracy, in which the Russian tradition associated with Lenin is opposed to and by the German tradition associated with social democracy, or, alternatively, “democratic socialism,” by contrast with the supposedly undemocratic socialism of Lenin, however justified or not by “Russian conditions.” The German model seems to stand for conditions more appropriate to advanced capitalist and liberal democratic countries.

Ralph Miliband is most famously noted for his perspective of “parliamentary socialism.” But this was not simply positive for Miliband but critical, namely, critical of the Labour Party in the UK. — It must be noted that Miliband’s sons are important leaders in the Labour Party today, among its most prominent neoliberal figures. Preceding his book on parliamentary socialism, Miliband wrote a critical essay in 1960, “The sickness of Labourism,” written for the very first issue of the newly minted New Left Review in 1960, in the aftermath of Labour’s dismal election failure in 1959, Miliband’s criticism of which, of course, the DSA/Jacobin cannot digest let alone assimilate. The DSA/Jacobin fall well below even a liberal such as Miliband — and not only because the U.S. Democratic Party is something less than the UK Labour Party, either in composition or organization. Miliband’s perspective thus figures for the DSA/Jacobin in a specifically symptomatic way, as an indication of limits and, we must admit, ultimate failure, for instance demonstrated by the recent fate of the Bernie Sanders Campaign as an attempted “electoral road” to “socialism,” this year as well as back in 2016 — the latter’s failure leading to the explosion in growth of the DSA itself. Neither Labour’s aspiration to socialism, whether back in the 1960s or more recently under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership, nor the DSA’s has come to any kind of even minimal fruition. Thus the specter — the haunting memory — of Lenin presents itself for our consideration today: How does Lenin hold out the promise of socialism?

Previously, I have written on several occasions on Lenin.[2] So I am tasked to say something today that I haven’t already said before. First of all, I want to address the elephant in the room (or is it the 800lb gorilla?), which is Stalinism, the apparent fate of supposed “Leninism” — which is also a demonstrated failure, however it is recalled today in its own peculiar way by the penchant for neo-Stalinism that seems to be an act of defiance, épater la bourgeoisie [shock the bourgeoisie], on the part of young (or not so young) Bohemian “Leftists,” in their deeply disappointed bitterness and antipathy towards the political status quo. “Leninism” means a certain antinomian nihilism — against which Lenin himself was deeply opposed.

An irony of history is that Lenin’s legacy has succumbed to the very thing against which he defined himself and from which his Marxism sharply departed, namely Narodnism, the Romantic rage of the supposedly “revolutionary” intelligentsia, who claimed — understood themselves — to identify with the oppressed and exploited masses, but really for whom the latter were just a sentimental image rather than a reality. Lenin would be extremely unhappy at what he — and indeed what revolution itself, let alone “socialism” — has come to symbolize today. Lenin was the very opposite of a Mao or a Che or Fidel. And he was also the opposite of Stalin. How so?

The three figures, Lenin, Stalin, and Trotsky, form the heart of the issue of the Russian Revolution and its momentous effect on the 20th century, still reverberating today. Trotsky disputed Stalin and the Soviet Union’s claim to the memory of Lenin, writing, in “Stalinism and Bolshevism” on the 20th anniversary of the Russian Revolution in 1937, that Stalinism was the “antithesis” of Bolshevism[3] — a loaded word, demanding specifically a dialectical approach to the problem. What did Lenin and Trotsky have in common as Marxists from which Stalin differed? Stalin’s policy of “socialism in one country” was the fatal compromise of not only the Russian Revolution, but of Marxism, and indeed of the very movement of proletarian socialism itself. Trotsky considered Stalinism to be the opportunist adaptation of Marxism to the failure of the world socialist revolution — the limiting of the revolution to Russia.

This verdict by Trotsky was not affected by the spread of “Communism” after WWII to Eastern Europe, China, Korea, Vietnam, and, later, Cuba. Each was an independent ostensibly “socialist” state — and by this very fact alone represented the betrayal of socialism. Their conflicts, antagonism and competition, including wars both “hot” and “cold,” for instance the alliance of Mao’s China with the United States against Soviet Russia and the Warsaw Pact, demonstrated the lie of their supposed “socialism.” Of course each side justified this by reference to the supposed capitulation to global imperialism by the other side. But the point is that all these states were part of the world capitalist status quo. It was that unshaken status quo that fatally compromised the ostensibly “socialist” aspirations of these national revolutions. Suffice it to say that Lenin would not have considered the outcome of the Russian Revolution or any subsequently that have sought to follow in its footsteps to be socialism — at all. Lenin would not have considered any of them to represent the true Marxist “dictatorship of the proletariat,” either. For Lenin, as for Marxism more generally, the dictatorship of the proletariat (never mind socialism) required the preponderant power over global capitalism world-wide, that is, victory in the core capitalist countries. This of course has never yet happened. So its correctness is an open question.

In his 1970 Lenin centenary essay, Miliband chose to address Lenin’s pamphlet on State and Revolution, an obvious choice to get at the heart of the issue of Lenin’s Stalinist legacy. But Miliband shares a great deal of assumptions with Stalinism. For one, the national-state framing of the question of socialism. But more importantly, Miliband like Stalinism elides the non-identity of the state and society, of political and social power, and hence of political and social revolution. Miliband calls this the problem of “authority.” In this is evoked not only the liberal-democratic but also the anarchist critique of not merely Leninism but Marxism itself. Miliband acknowledges that indeed the problem touched on by Lenin on revolution and the state goes to the heart of Marxism, namely, to the issue of the Marxist perspective on the necessity of the dictatorship of the proletariat, which Marx considered his only real and essential original contribution to socialism.

In 1917, Lenin was accused of “assuming the vacant throne of Bakunin” in calling for “all power to the soviets [workers and soldiers councils].” — Indeed, Miliband’s choice of Lenin’s writings, The State and Revolution, written in the year of the 1917 Russian Revolution, is considered Lenin’s most anarchist or at least libertarian text. Lenin’s critics accused him of regressing to pre-Marxian socialism and neglecting the developed Marxist political perspective on socialist revolution as the majority action by the working class, reverting instead to putschism or falling back on minority political action. This is not merely due to the minority numbers of the industrial working class in majority peasant Russia but also and especially the minority status of Lenin’s Bolshevik Communist Party, as opposed to the majority socialists of Socialist Revolutionaries and Menshevik Social Democrats, as well as of non-party socialists such as anarchist currents of various tendencies, some of whom were indeed critical of the anarchist legacy of Bakunin himself. Bakunin is infamous for his idea of the “invisible dictatorship” of conscious revolutionaries coordinating the otherwise spontaneous action of the masses to success — apparently repeating the early history of the “revolutionary conspiracy” of Blanqui in the era of the Revolution of 1848. But what was and why did Bakunin hold his perspective on the supposed “invisible dictatorship”? Marxism considered it the corollary — the complementary “opposite” — of the Bonapartist capitalist state, with its paranoiac Orwellian character of subordinating society through society’s own complicity in the inevitable authoritarianism — the blind social compulsion — of capitalism, to which everyone was subject, and in which both and neither everyone’s and no one’s interests are truly represented. Bakunin’s “invisible dictatorship” was not meant to dominate but facilitate the self-emancipation of the people themselves. — So was Lenin’s — Marxism’s — political party for socialist revolution.

Lenin has of course been accused of the opposite tendency from anarchism, namely of being a Lassallean or “state” socialist. Lenin’s The State and Revolution drew most heavily on Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Programme, attacking the Lassalleanism of the programme of the new Social-Democratic Party of Germany at its founding in 1875. So this raises the question of the specific role of the political party for Marxism: Does it lead inevitably to statism? The history of ostensible “Leninism” in Stalinism seems to demonstrate so. The antinomical contrary interpretations of Lenin — libertarian vs. authoritarian, statist vs. anarchist, liberal vs. democratic — are not due to some inconsistency or aporia in Lenin or in Marxism itself — as Miliband for one thought — but are rather due to the contradictory nature of capitalism itself, which affects the way its political tasks appear, calling for opposed solutions. The question is Marxism’s self-consciousness of this phenomenon — Lenin’s awareness and consciously deliberate political pursuit of socialism under such contradictory conditions.

The history of Marxism regarding rival currents in socialism represented by Lassalle and Bakunin must be addressed in terms of how Marxism thought it overcame the dispute between social and political action — between anarchism and statism — as a phenomenon of antinomies of capitalism, namely, the need for both political and social action to overcome the contradiction of capitalist production in society. This was the necessary role of the mass political party for socialism, to link the required social and political action. Such mediation was not meant to temper or alleviate the contradiction between political and social action — between statism and anarchism — but rather to embody and in certain respects exacerbate the contradiction.

Marxism was not some reconciled synthesis of anarchism and statism, a happy medium between the two, but rather actively took up — “sublated,” so to speak — the contradiction between them as a practical task, regarding the conflict in the socialist movement as an expression of the contradiction of capitalism, from which socialism was of course not free. There is not a question of abstract principles — supposed libertarian vs. authoritarian socialism — but rather the real movement of history in capitalism in which socialism is inextricably bound up. Positively: Lenin called for overcoming capitalism on the basis of capitalism itself, which also means from within the self-contradiction of socialism.

Lenin stands accused of Blanquism. The 19th century socialist Louis Auguste Blanqui gets a bad rap for his perspective of “revolutionary conspiracy” to overthrow the state. For Blanqui, such revolutionary political action was not itself meant to achieve socialism, but rather to clear the way for the people themselves to achieve socialism through their social action freed from domination by the capitalist state.

Miliband is at best what Marx/ism would have considered a “petit bourgeois socialist.” But really he was a liberal, albeit under 20th century conditions of advanced late capitalism. What does this mean? It is about the attitude towards the capitalist state. The predecessor to Bakunin, Proudhon, the inventor of “anarchism” per se, was coldly neutral towards the Revolution of 1848, but afterwards oriented positively towards the post-1848 President of the 2nd Republic, Louis Bonaparte, especially after his coup d’état establishing the 2nd Empire. This is because Proudhon, while hostile to the state as such, still considered the Bonapartist state a potential temporary ally against the capitalist bourgeoisie. Proudhon’s apparent opposite, the “statist socialist” Ferdinand Lassalle had a similar positive orientation towards the eventual first Chancellor of the Prussian Empire Kaiserreich, Bismarck, as an ally against the capitalist bourgeoisie — Bismarck who infamously said that the results of the 1848 Revolution demonstrated that not popular assemblies but rather “blood and iron” would solve the pressing political issues of the day. In this was recapitulated the old post-Renaissance alliance of the emergent bourgeoisie — the new free city-states — with the Absolutist Monarchy against the feudal aristocracy.

The 20th century social-democratic welfare state is the inheritor of such Bonapartism in the capitalist state — Bismarckism, etc. For instance, Efraim Carlebach has written of the late 19th century Fabian socialist enthusiasm for Bismarck from which the UK Labour Party historically originated[4] — the Labour Party replaced and inherited the role of the Liberal Party in the UK, which had represented the working class, especially its organization in labor unions. The Labour Party arose in the period of Progressivism — progressive liberalism — and progressive liberals around the world, such as for instance Theodore Roosevelt in the U.S., were inspired by Wilhelmine Germany that was founded by Bismarck, specifically Bismarck as the founder of the welfare state. Bismarck’s welfare state provisions were made long before the socialists were any kind of real political threat. The welfare state has always been a police measure and not a compromise with the working class. Indeed socialists historically rejected the welfare state — this hostility only changed in the 1930s, with the Stalinist adoption of the People’s Front against fascism and its positive orientation towards progressive liberal democracy.

Pre-WWI Wilhelmine Germany was considered at the time progressive and indeed liberal, part of the greater era’s progressive liberal development of capitalism — which was opposed by contemporary socialists under Marxist leadership. But by conflating state and society in the category of “authority,” further obscured by the question of “democracy,” Miliband expresses the liquidation of Marxism into statism — Miliband assumes the Bonapartism of the capitalist state, regarding the difference of socialism as one of mere policy, for instance the policies pursued by the state that supposedly serve one group — say, capitalists or workers — over others. This expresses a tension — indeed contradiction — between liberalism and democracy. This contradiction is often mistaken for that of liberalism versus socialism, as for instance by the post-20th century “Left” going back to the 1930s Stalinist era of the Communist Party’s alliance with progressive liberals in support of FDR’s New Deal, whose history is expressed today by DSA/Jacobin.

For Lenin, by contrast, the issue of politics — and hence of proletarian socialism — is not of what is being done, but rather of who is doing it. The criterion of socialism for Marxism such as Lenin’s is the activity of the working class — or lack thereof. The socialist revolution and the political regime of the dictatorship of the proletariat was not for Lenin the achievement of socialism but rather its mere precondition, opening the door to the self-transformation of society beyond capitalism led by the — “dictatorship,” or social preponderance, preponderance of social power — of the working class. Without this, it is inevitable that the state serves rather not the interests of the capitalists as a social group but rather the imperatives of capital, which is different. For Lenin, the necessary dictatorship of the proletariat was the highest form of capitalism — meaning capitalism brought to highest level of politics and hence of potentially working through its social self-contradictions — and not yet socialism — meaning not yet even the overcoming of capitalism.

By equating the capitalist welfare state with socialism, with the only remaining criterion the democratic self-governance of the working class, Miliband by contrast elided the crucial Marxist distinction between the dictatorship of the proletariat and socialism. For Miliband, what made the state socialist or not was the degree of supposed “workers’ democracy.” — In this way, Miliband serves very well to articulate the current DSA/Jacobin identification of its political goals with “democratic socialism.” But, like Miliband, DSA/Jacobin falls prey to the issue of the policies pursued by the state as the criterion of socialism, however without Miliband’s recognition of the difference between (social-democratic welfare state) policies pursued by capitalist politicians vs. by the working class itself.

Lenin pursued the political and social power — the social and political revolution — of the working class as not the ultimate goal but rather the “next necessary step” in the history of capitalism leading — hopefully — to its self-overcoming in socialism. As a Marxist, Lenin was very sober and clear-eyed — unsentimental — about the actual political and social tasks of the struggle for socialism — what they were and what they were not.

In harking back to the manifest impasse of the mid-20th century capitalist welfare state registered by Miliband, however through identifying this with the alleged limits of Lenin’s and greater Marxism’s consciousness of the problem, but without proper recognition of its true nature in capitalism, those such as DSA/Jacobin actively obfuscate, bury and forget, not Marxism such as Lenin’s, or the goal of socialism, but rather the actual problem of capitalism they are trying to confront, obscuring it still further.

The “Left” today such as DSA/Jacobin wants the restoration of pre-neoliberal progressive capitalism, for instance the pre-neoliberal politics of the UK Labour Party — or indeed simply the pre-neoliberal Democrats. Their misuse of the label “socialism” and abuse of “Marxism,” including even the memory of Lenin and their bandying about of the word “revolution,” is overwrought and in the service of progressive capitalism. This is an utter travesty of socialism, Marxism, and the memory of Lenin.

On the 150th anniversary of Lenin’s birth, we owe him at least the thought that what he consciously recognized and actually pursued as a Marxist be remembered properly and not falsified — and certainly not in the interest of seeking, by sharp contrast to Lenin, the “democratic” legitimation of capitalism, which even liberals such as Ralph Miliband acknowledged to be a deep problem afflicting contemporary society and its supposed “welfare” state. By reckoning with what Marxists such as Lenin understood as the real problem and actual political tasks of capitalism, there is yet hope that we will resume the true socialist pursuit of actually overcoming it.

Postscript: On Jacobin’s defense of Miliband contra Lenin

Longtime DSA member and Publisher and Editor of Jacobin magazine Bhaskar Sunkara responded to my critique of Ralph Miliband by interviewing Leo Panitch of the Socialist Register on Jacobin’s YouTube broadcast Stay at Home #29 of April 27, 2020.[5] Sunkara has previously stated that rather than a follower of Lenin or Kautsky, he is a follower of Miliband. Sunkara and Panitch were eager to defend Miliband’s socialist bona fides against my calling him a liberal, but what they argued confirmed my understanding of Miliband as a liberal and not a socialist let alone a Marxist. The issue is indeed one of the state and revolution. It is not, as Panitch asserted in the interview, a matter of political “pluralism” in socialism.

Panitch, who claims Miliband as an important mentor figure, spoke at a Platypus public forum panel discussion in Halifax in January 2015 on the meaning of political party for the Left, and observed in his prepared opening remarks that in the 50 years between 1870 and 1920 — Lenin’s time — there took place the first and as yet only time in history when the subaltern have organized themselves as a political force.[6] In his interview with Sunkara on Miliband, Panitch now claims that Lenin’s strategy — which was that of 2nd International Marxism as a whole, for instance by Karl Kautsky, Rosa Luxemburg, Eugene Debs, et al. — of replacing the capitalist state with the organizations of the working class that had been built up by the socialist political party before the revolution, was invalidated by the historical experience of the 20th century. Instead, according to Panitch, the existing liberal democratic capitalist state was to provide the means to achieve socialism. This is because it is supposedly no longer a state of capitalists but rather one committed to capitalism: committed to capital accumulation. But Marxism always considered it to be so: Bonapartist management of capitalism in political liberal democracy.

Panitch claims that Miliband’s critique of the UK Labour Party was in its Fabian dogma of “educating the ruling class in socialism through the state,” whereas socialists would instead “educate the working class in socialism through the state.” But Lenin and other Marxists considered the essential education of the working class in the necessity of socialism to take place through its “class struggle” under capitalism — its struggle as a class to constitute itself as a revolutionary force — in which it built its civil social organizations and political parties aiming to take political and social — state — power. Panitch condemns Lenin for his allegedly violent vision of the overthrow of the capitalist state and replacing it with a revolutionary workers state — the infamous “dictatorship of the proletariat” always envisioned by Marxism.

Thus Panitch condemns the Marxist perspective on proletarian socialist revolution per se. But the question for Lenin and other Marxists was not revolution as a strategy — they were not dogmatic “revolutionists” as opposed to reformists — but rather the inevitability of capitalist crisis and hence the inevitability of political and social revolution. The only question was whether and how the working class would have the political means to turn the revolution of inevitable capitalist crisis into potential political and social revolution leading to socialism. By abandoning this Marxist perspective on revolution — which Miliband himself importantly did not rule out — Panitch and Sunkara along with DSA/Jacobin do indeed articulate a liberal democratic and not proletarian socialist let alone Marxist politics. | P

[1] “Lenin’s The State and Revolution,” Jacobin (August 2018), available online at: <https://www.jacobinmag.com/2018/08/lenin-state-and-revolution-miliband>.

[2] See my: “The Decline of the Left in the 20th Century: Toward a Theory of Historical Regression: 1917,” Platypus Review #17 (November 2009), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2009/11/18/the-decline-of-the-left-in-the-20th-century-1917/>; “Lenin’s liberalism,” PR #36 (June 2011), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2011/06/01/lenins-liberalism/>; “Lenin’s politics,” PR #40 (October 2011), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2011/09/25/lenins-politics/>; “The relevance of Lenin today,” PR #48 (July–August 2012), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2012/07/01/the-relevance-of-lenin-today/>; and “1917–2017,” PR #99 (September 2017), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2017/08/29/1917-2017/>.

[3] Available online at: <https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1937/08/stalinism.htm>.

[4] “Labour once more,” Platypus Review #123 (February 2020), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2020/02/01/labour-once-more/>.

[5] Watch at: <https://youtu.be/oBJR3xfmgA4>.

[6] Transcript published in Platypus Review #74 (March 2015), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2015/03/01/political-party-left-2/>.