Labour once more

Efraim Carlebach

Platypus Review 123 | February 2020

Author’s note: This article was originally presented as a teach-in on the history of the Labour Left[1] given to the Platypus chapter at the London School of Economics on December 5, 2019, a week before the UK election, in which Boris Johnson’s Conservatives won a landslide majority and inflicted a resounding defeat on Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour. The argument follows that of my article “‘Last illusions’: The Labour Party and the Left,” published in issue 97 of this review in 2017.[2] Not much has changed since 2017 nor since the election results were announced in December.

Foreword: after the election

IN THE BUBBLE OF ELITE UNIVERSITIES and among circles of urban young professionals, where Leftists dedicated many hours to door-knocking for Labour, a false optimism about Labour’s chances was betrayed by the insistence that anyone who did not join in it was morally suspect. Gone were questions about socialism and how Labour was to be “transformed.” Meanwhile, Corbynism had only continued Blair’s yuppification of the Labour party. The Corbynistas were in for a shock.[3] “Look at all those white people!” said a woman next to me, with palpable disdain, at a watching party as the result came in from Blythe Valley. She’s clearly never been to the northeast. Totally disoriented by Brexit, the Left — which had bet everything on Corbynism — became the last defenders of neoliberalism.

The Conservative victory has exacerbated the pre-existing division on the Left between those who favored an orientation towards pro-Brexit voters in the post-industrial “heartlands” and those who favored an orientation towards the “progressive” alliance of students, ethnic minorities and precarious urban workers. Rather than raising fundamental questions for the Left, the defeat allows both sides to double down on their Labour orientation, arguing about what could have been. Both sides call it “Labour’s loss,” avoiding mention of the Conservatives’ victory. Both sides propound the myth that a Labour government would be somehow closer to “socialism” than a Conservative one.

Those who backed a pro-Brexit orientation to revive a “Left populism” are right to point out the working class’s revolt against Labour, but they are ambivalent about it, fumbling around with a pre-neoliberal vision of social democracy, which is never going to return. This orientation obscures the question of post-neoliberalism, as its proponents imagine a simple reversal of neoliberalism at the level of policy backed by restored party institutions. The real crisis of post-war social democracy and the emergence of the New Left is avoided. “Working-class independence” is understood simply sociologically, as against the “professional managerial class” they chide. The Marxist concept of political independence is avoided.

Those on the “far Left” who have been committed for four years to justifying support for Corbyn and “socialism” now claim they knew it was never going to work, falling back on their old demands for extra-parliamentary street protests. Lindsey German and Tariq Ali will try to revive the Stop the War Coalition, but capitalist politics is not about to return to 2003. Socialist Appeal/IMT, which campaigned for a Labour government “with socialist policies,” told their activists, “Don’t believe the polls or pessimists — we can win!”[4] Now they are reorienting towards global protests with their Marxist Student Federation Conference theme “World in Revolt” (last year it was “The fight for socialism today”). But a sharp turn may throw off many of those politicized by Corbynism, who will be happy to settle for Rebecca Long-Bailey or Clive Lewis (or even Keir Starmer) and depoliticized disgust with “evil Tories” — that thorny thought taboo which the Left has taught to another generation. The symbiotic relation between the Labour Left and Right rolls on.

***

Symbiotic relationship

The near universal support for Corbyn’s Labour party from the Left has been the latest chapter of its decomposition, in which the Left has adapted itself to changes within capitalism, claiming out of despair that each new thing is the chance in the fight for socialism, and then, when it turns out not to be so, supporting it anyway. The Left has become conservative, opposing changes in capitalism, thus avoiding the question of how such changes point to new possibilities. Millennials who joined ostensibly revolutionary organizations in the anti-war or anti-austerity protests all settled for Corbyn’s “kinder, gentler politics.”

I concluded my 2017 article on Labour and the Left with Hillel Ticktin’s assessment of Corbyn and McDonnell: “While Corbyn and McDonnell both talk about socialism, they are not even very radical, let alone socialist.”[5] The Labour Right, however, stigmatized McDonell’s meager policies as “socialist.” Ticktin noted that this “shows the nature of rightwing Labour — it does not understand the system it is supporting.” I agreed, adding: “What does it show about the Left today that they share the same fantasy?” That is, the fantasy that this has anything to do with socialism, a term that in 2016 was really just a label for being passionately anti-Trump or anti-Brexit.

A week before the election, even such fantastical talk of socialism has been dropped in favor of just defending the NHS and stopping Brexit, for which perhaps millions of working-class voters will abandon Labour for the Tories — indeed, many already have.

The attempts to “transform” the Labour party have failed. There have been at least three different splits from Momentum, going back to early 2017. All of these have fizzled out, yet their disgruntled leaders will still support Labour. The idea that it wasn’t about supporting Corbyn but “transforming Labour” turns out to have been an enabling myth.

Remember when Leftists said that backing the Labour Left to revive social democracy was a dead end? Like when Mark Fisher wrote in 2009 that “capitalist realism need not be neoliberal… capitalism could revert to a model of social democracy… Without a credible and coherent alternative to capitalism, capitalist realism will continue”?[6] Or when the Sparticist League argued that there was “no choice” between Tony Benn and Neil Kinnock in 1988?[7] But once the “fight in the Labour party” was on in 2016, everyone from Fisher to the Sparts supported Corbyn, the former believing that we were riding a “wave… towards post-capitalism”[8] and the latter declaring Labour’s internal disputes to be a “class war.”[9]

The Left has been caught up in what the Sparticist League described acutely in 1988 as a “symbiotic relationship”:

“Benn’s campaign has been portrayed by the bourgeois press and most of the ostensibly socialist left as a David and Goliath battle for the ‘socialist soul’ of the party against Kinnock/Hattersley’s overt scabbing and ‘new realism.’ But the Labour ‘lefts’ indulgence in the timeworn reformist rhetoric of the parliamentary road to democratic socialism, ‘unilateralism,’ non-alignment, disarmament and nationalist ‘Little England’ protectionism is no alternative to Kinnock’s more reactionary agenda for class peace in Thatcher’s Britain. Indeed, this contest reflects the classic and historic symbiotic relation between the Labour ‘left’ and right that has maintained the party for decades as the primary obstacle to proletarian revolution on these isles.”[10]

Since 2015, Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour party has been presented in similar histrionic terms, “a David and Goliath battle for the ‘socialist soul’ of the party.” The illusion of fighting the Right, whether within the Labour party, or supporting the Labour party in whatever form just to “kick the Tories out,” has replenished the Labour party with activists for generations and kept the Left chained to its tail.

What is this symbiotic relationship, and how has it come about?

From Chartism to Labourism: “progressive” Bonapartism

The appearance of the class struggle in politics in the 1830s and 40s was a symptom of the crisis of bourgeois society — not its cause. Marx took “class” to be a historical and not a sociological category. The task of the proletariat, he wrote, was to abolish itself, not to realize itself.

Chartism and the revolutions of 1848 failed to lead to the “social republic.” Instead, a new form of state arose over society, wielding welfare programs and police forces to manage the contradictions. This was clearly expressed in the election and then coup of Louis Bonaparte, with mass popular support from all sections of society. Under these conditions of Bonapartism, Marx recognized in a new way both the political independence of the working class from bourgeois liberals and radicals and the dictatorship of the proletariat as necessary political forms for overcoming the state and capitalism.

This insight was the foundation for the Social Democratic parties of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which sought, through the Second International, to build the independent working-class force for an international revolution.

Bonapartism has been the condition of capitalist politics ever since. It was exemplified in Britain by Palmerston and Gladstone’s Liberal reform administrations and Disraeli’s “One Nation” Conservatism. The politics of the representation of labor in Britain from the post-Chartist period onwards was a form of adaptation to the prevailing state capitalism, unlike the socialists’ attempts to point beyond such conditions.

The organized trade union movement mostly sought parliamentary representation through the Liberal Party. This was embodied by A. J. Mundella, the first representative of labor elected to parliament in 1868, a year after the ’67 reform act gave some working-class people the vote and the same year that the Trade Union Congress (TUC) was founded. Mundella had been a Chartist and poet, and at 15 heard his ballads sung in Chartist meetings. He went on to become a successful capitalist and partner in a large manufacturing firm. As the representative of labor, he was elected on the Liberal Party ticket and served in numerous administrations, helping to pass the trade union reforms of the early 1870s.

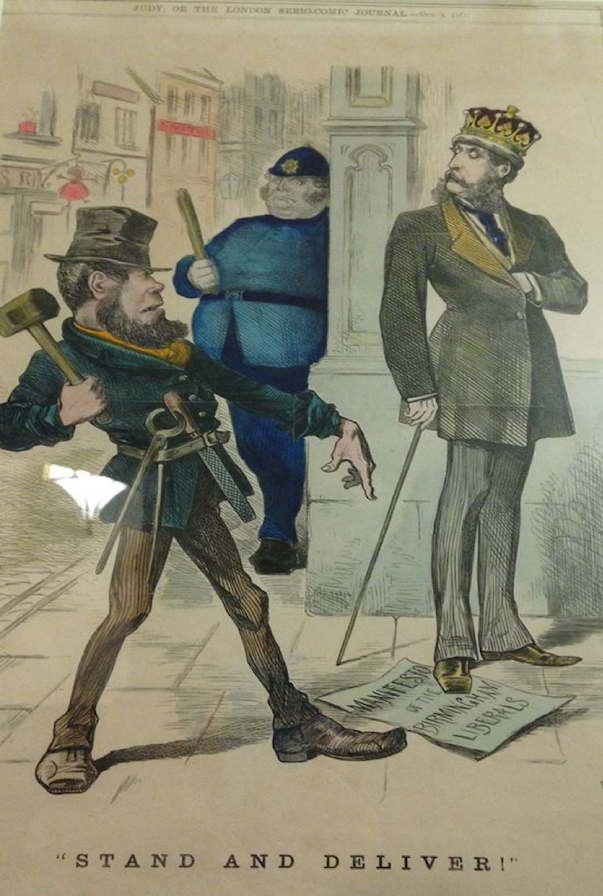

The politics of Bonapartism are captured well by a cartoon from 1871. The Liberal Gladstone stands on a copy of the “Manifesto of the Birmingham Liberals,” while a worker, tools at the ready, points at the manifesto, demanding that Gladstone “stand and deliver!” The worker is demanding his bourgeois right to the value of his labor. But, as Marx said, “Between equal rights force decides.”[11] A zombie-like policeman is coming down towards them, baton at the ready. Someone—it’s not clear who—is going to get their head smashed in. In the background hang three gold balls, symbol of the pawnshop, indicating the lingering threat of unemployment that underpins this political dynamic.

The Labour Party that emerged in 1906 continued this Bonapartist politics of the Liberal representation of labor in the capitalist state, against attempts to establish a socialist party seeking to organise the working class independently to go beyond capitalism. As Theodore Rothstein wrote in From Chartism to Labourism:

“After 1848 a new chapter is opened in the social history of England — not a chapter perhaps, but a whole volume — and this new volume has an entirely different content, and is permeated with quite a different spirit. If on the Continent of Europe the year 1848 marked the appearance of the proletariat upon the stage, henceforth fighting for its emancipation, in England it marked the moment of the retreat of the proletariat, henceforth tied body and soul to the triumphal chariot of the bourgeoisie, which it is dragging along to this day.”[12]

Attempts to break the British working class away from Liberal labor representation to a mass socialist party failed. In the 1880s, three very different socialist groups emerged. Henry Hyndman founded the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) in 1881. A somewhat irreverent follower of Marx, he hoped to establish a mass socialist party on the model of the Second International. In 1884, economists Sidney and Beatrice Webb founded the Fabian Society, committed to Bonapartist welfare and social reform on the Bismarckian model. In 1889, Keir Hardie formed the Independent Labour Party (ILP), championing parliamentary representation of labor separate from the Liberals, at least formally. All three groups tried to gain working class support through the TUC. In the 1880s and 90s, the efforts of the SDF to push for an independent socialist class politics were repeatedly blocked by the trade unions, and their attempts to unify with the ILP failed.

The Liberal Party welcomed the new Labour representatives, whose votes supported the Liberal governments, and stood aside in many seats to let the Labour candidate win. Sometimes a clash would emerge between an independent labor candidate and the Liberal labor candidate. The Labour Representation Committee (LRC) was formed in 1900 to avoid this happening and ensure the greatest number of representatives of labor in Parliament. Again, the three socialist groups joined, but the efforts of the SDF to push for an independent class politics and socialist goal were rejected, and they walked out a year later.

In 1906, 29 LRC candidates were returned, a majority with the support of the Liberals, who, for example, stood aside for Keir Hardie to win his seat. Ramsay MacDonald, future Labour prime minister and theoretician of the ILP, was also elected that year. He summarized the group’s politics succinctly: “The watchword of socialism is not class consciousness but community consciousness.”[13] This “community consciousness” was a parallel to Disraeli’s “one nation” Conservatism: Bonapartism.

The SDF continued unsuccessfully to try to build a British socialist party in the Second International, opposing the Labour Party and the Liberals. The commitment of the newly christened Labour Party to Liberal social reforms was embodied in the 1910 general elections. Lloyd George’s “People’s Budget” — was this echoed by McDonnell’s “People’s Chancellor”? — promised large social welfare reforms, but it was blocked by the House of Lords. A “People vs Parliament” election — as Boris Johnson has branded that of 2019 — was called to push through the reforms. The Liberals won with Labour’s support.

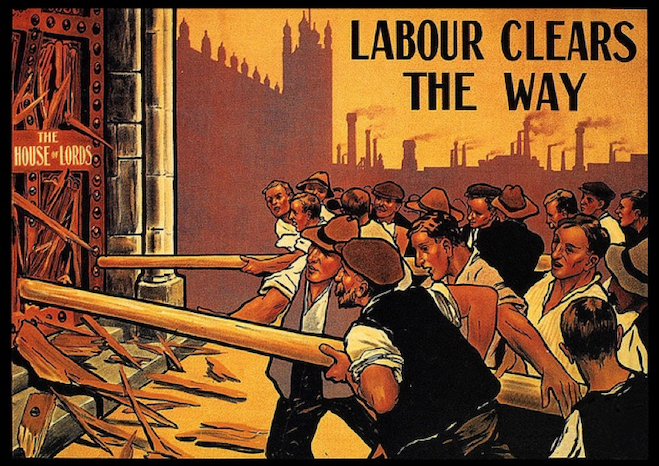

A famous poster from this election is often used on the Left as an example of Labour’s early radicalism. It shows men using battering rams to open the House of Lords. The caption reads, “Labour clears the way.” Labour clears the way — for what? For Socialism? No. For the Liberal reforms, which were blocked by the House of Lords. It is literally Labour being used as a battering ram by the Liberals. This is a good example of the “progressive” capitalist politics that the Left has been supporting since the 1930s — if not the 1910s. It was exemplified in the U.S. by Teddy Roosevelt’s “progressivism.”[14]

The SDF cautioned its supporters against any illusions in the supposed “lesser evil” of the Liberal government supported by the Labour party. Dora Montefiore wrote in Justice:

“[A]s far as our side was concerned the election has been fought absolutely and purely on Socialist teachings; the Budget has been attacked and riddled and ridiculed as far as the plea of its being a “poor man’s Budget” is concerned. There has been no truckling to any “restricting the veto of the Lords”; but we have pointed again and again to our programme, which demands the “abolition of the House of Lords.” Whilst detailing the few immediate palliatives which must be conceded in order to mitigate the terrible sufferings entailed by capitalism, we have spoken ever of Revolutionary Socialism as being the only hope of the workers; and they have responded with a cheer for Social Democracy.”[15]

In 1911, some sections of the ILP, unhappy with the direction of the LRC in supporting the Liberals, broke away and joined the SDF, becoming the British Socialist Party (BSP).

Lenin and Labour

The international socialist movement came into crisis during WWI as the German socialists voted to support war credits. The Labour Party duly voted through the war budgets for the Liberal government.[16] The BSP also split, with Hyndman leading out a pro-war faction. The revolutionary opportunity posed by this crisis led to the Russian revolution and the formation of communist parties out of the remnants of former socialist parties. In Britain, the Communist Party was formed by the BSP and several smaller groups. Arguments immediately broke out within the CPGB as to how to orient towards the Labour Party — how to win the working class away from Labour.

This debate occasioned Lenin’s famous speech on affiliation with the Labour Party in 1920, which has been much abused by Leftists today seeking justification for their activity in Labour. The Labour Party at the time was still a very loose organization to which other parties (such as the BSP) could affiliate and had. This was a unique situation, in which the CPGB could attempt to affiliate and publicly agitate against the Labour leadership.

Lenin criticized the view that Labour was the “political expression” of the working class:

“The concept ‘political expression’ of the trade union movement, is erroneous. Of course, most of the Labour Party’s members are workingmen. However, whether or not a party is really a political party of the workers does not depend solely upon a membership of workers but also upon the men that lead it, and the content of its actions and its political tactics. Only this latter determines whether we really have before us a political party of the proletariat. Regarded from this, the only correct, point of view, the Labour Party is a thoroughly bourgeois party, because, although made up of workers, it is led by reactionaries, and the worst kind of reactionaries at that, who act quite in the spirit of the bourgeoisie. It is an organisation of the bourgeoisie, which exists to systematically dupe the workers”.[17]

Here Lenin is drawing on Marx’s lessons of 1848: the necessity of political independence of the working class for socialism, as opposed to trade unionism and Bonapartist reforms within capitalism. Further, following Marx, Lenin assumes that it is the goal of socialism that constitutes the proletariat politically as such; otherwise, the working class is just another racket within capitalism. Similarly, when Eduard Bernstein, inspired by the British trade union movement, advanced his “revisionist” socialism in Germany, saying, “the movement is everything, the goal is nothing,” Rosa Luxemburg upheld the Marxist view that,

“[T]he final goal of socialism constitutes the only decisive factor distinguishing the Social-Democratic movement from bourgeois democracy and from bourgeois radicalism, the only factor transforming the entire labour movement from a vain effort to repair the capitalist order into a class struggle against this order, for the suppression of this order.”[18]

Given the open nature of the Labour Party, Lenin called for the CPGB to affiliate but to maintain complete freedom of press and organization and to begin agitating against the Labour leadership. When Sylvia Pankhurst responded that Labour would immediately kick them out if they did so, Lenin responded that that would be excellent, as it would publicly demonstrate to the working class that the Labour party “is an organisation of the bourgeoisie, which exists to systematically dupe the workers.” It was on that basis that affiliation with the Labour Party was called for — to support it like a rope supports a hanged man.

In the end, Labour did not accept CPGB affiliation, and when CPGB members joined individually, they were witch-hunted out over the 1920s.[19] The window of opportunity quickly closed as the German revolution failed, Lenin died and Stalinism began to take its hold on the Third International, and, at the same time, the Labour Party became the official opposition and then joint governing party with the Liberals, becoming a more tightly controlled organization and squeezing out the efforts of the early CPGB to lead the working class away from Labourism. In the absence of an independent Socialist or Communist party, in the absence of an International and in the absence of the working-class radicalism that followed WWI, quoting Lenin to justify working with Labour reversed the who/whom question Lenin posed. Rather than the Left using the Labour Party, the Labour Party has used the Left ever since.

The Stalinist CPGB, through all its various zigzags, accommodated to tacit support for Labour through its so-called “British road to socialism.” The Trotskyists who split from the CPGB tried from the 30s to the 50s every different form of possible relationship to Labour, to try to win workers away from it or transform it in some way.[20] Meanwhile, Labour was growing into an establishment governing party of British capitalism, particularly through the experience of the national unity government in WWII.

The ’45 Labour government was not a victory for socialism, but rather the state management of capitalism, as we have been tracing from the Bonapartism of the 1860s. The post-war order was not even really modelled on Keynesian and Fabian policy but on America’s four freedoms, the Marshall plan and FDR’s New Deal. The essential conservatism of the welfare state was revealed by the fact that it became the consensus for the Conservative party, too, which managed the welfare state throughout the 1950s.

When Labour lost the 1959 election, the party went into crisis, and the SPGB, a tiny split from the old SDF, observed: “When the pioneers of the Labour Party dreamed of placing themselves at the head of a grateful army of electors by enacting social reforms, they never thought of a possibility of a Tory Party that beat them at the same game.”[21]

Young Socialists

This crisis for Labourism was expressed through so-called left-wing discontents within the party. A great battle took place at its 1960 Scarborough conference between the “Left” and “Right” of the party over Clause IV and nuclear disarmament. The Left won the battle but lost the war. At the same time, official Communism had come into a crisis of its own following the Soviet invasion of Hungary in ’56 and Khrushchev’s speech denouncing Stalin.

This simultaneous crisis of Stalinism and Labourism opened up possibilities for rethinking on the Left, giving rise in the UK to what we now call the New Left. New Left Review was launched in January 1960 as a direct response to Labour’s defeat, featuring Ralph Miliband’s article “The Sickness of Labourism.”[22] It is significant that Miliband opened the essay with a quote from Disraeli in conversation with Henry Hyndman. When Hyndman visited him to ask for advice on how to start a mass Socialist party, Disraeli responded, “It is a very difficult country to move, Mr. Hyndman, very difficult indeed.” Miliband’s “Sickness of Labourism” invoked the difficult problem of beginning an independent socialist party. But perhaps the deep history he invoked was illegible to his readers.

The Trotskyists of Labour Review tried to engage in the new intellectual climate for rethinking Marxism. Their 1960 issue on the famous Scarborough conference features Cliff Slaughter’s valuable essay “What is Revolutionary Leadership?” Early issues also had interesting debates between Slaughter and Alasdair MacIntyre (later of the IS) over the question of the “New Left.” The period from Labour’s defeat in 1959 to its election victory in 1964 was one of the most vibrant and thoughtful on the British Left since the 1920s. Was there a possibility for overcoming the “symbiotic” relationship between Left and Right within Labour? Was there a chance to “transform” Labour? What would that have meant? Was there the possibility for breaking from Labourism and founding a new independent socialist politics?

The Labour Party itself was worried after so many defeats. It needed to attract some of the youthful energy it could see protesting for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) at its conference. It needed to use the symbiotic relationship between Left and Right to perpetuate itself. It decided to set up a youth organization called Young Socialists (YS).

YS grew rapidly with support from young people who had only ever known Conservative rule and found the welfare state to be conformist and restrictive and who opposed nuclear weapons and American foreign policy. The different Trotskyist groups all entered, too, and tried to build their organizations by gaining influence in the Labour Party through YS. [23] More broadly, YS tried to “transform” Labour. There was a vibrant social scene, and the YS papers ran column after column on the radical culture of the swinging 60s (this was mocked at the time as “sex, syncopation and socialism”). They demanded that Labour endorse unilateral disarmament and withdrawal from NATO. As Young Guard, the minority paper in YS, wrote in 1963:

“It is vital that the voice of socialism is heard at this conference. We must demand full discussion of the important issues of wages and nationalisation and press home the socialist answers in the interests of Labour and of the working masses who are now looking to Labour for a lead.”[24]

Through the early 60s, this put a growing YS, with hundreds of national branches, at odds with the Labour leadership, compounding a “Left/Right” dynamic in the party.

When Labour ran in the 1964 election under Harold Wilson, it was seen as the chance of a lifetime for these “young socialists.” Wilson and his ally Barbara Castle both came from the Bevanite Left wing of the Labour party, which had opposed the party’s rightward shift in the 50s under Gaitskell. The Tories had been in power for 13 years and were engulfed in scandals following the Suez war. A young Tony Benn, fresh from a career at the BBC, led Labour’s new-fangled television campaign with all the latest media-savvy ideas. Wilson spoke about how Labour was going to harness the new technological revolution.

For most YS members, as the election approached, it began to matter less and less that Labour was not going to endorse nuclear disarmament, nor withdraw from NATO or complete the set of nationalizations or the wages policy they had wanted. Rather, they were drawn into the idea that getting rid of the Tories would be the best chance in their lifetimes to vaguely advance socialism. “After the election,” they thought, “we will push on from there. The working classes,” who, as Young Guard had put it, were looking to Labour for a lead, “would probably become emboldened and demand more.” These and other illusions helped them to wholeheartedly endorse Harold Wilson’s Labour Party in 1964 and celebrate its victory. The small window of opportunity for rethinking the necessity of socialism, the problem of working-class political independence, the tradition of Marxism and the relation of the Left to the Labour party had closed on this New Left.

While most Young Socialists went along with the course of the Wilson Government, a minority voiced dissent. What is more colloquially considered the New Left is what came after ’64: the young socialists who were discontented with the realities of the Labour government. But despite the organizations they set up outside Labour in the 70s (a long story I can’t get into here), they all still tacitly supported Labour as Thatcher’s revolution rocked their world, and as mature adults they probably voted for Tony Blair, who promised the same relief from years of Tory government to another generation.

This dynamic was a consistent feature of the talks at a panel on “50 Years of 1968”[25] at the Platypus European conference in London in February 2018. Nearly all of the panelists spoke about disappointment with the Labour government of the mid 60s in the attempt to push them towards Left-wing politics. Judith Shapiro, a one-time member of the Sparticist League, recalled with horror, word for word, the news statement that Labour was giving tacit support to the U.S. troops in Vietnam. Despite her revolutionary Trotskyism, her real leftism manifested itself as disappointment with Labour: feeling betrayed. Benn comes to seem like disgruntled Wilsonites, and Wilson, disgruntled Bevanites. The Left goes on prosecuting the “symbiotic relationship” within Labour eternally.

The neoliberal Left

“The British general election of 1997 brought an ignominious end to eighteen years of Conservative rule. In its hour of victory, New Labour should recall how exacting modern electorates are prone to be. Despite its extraordinary caution, New Labour still managed to promise the beginnings of a badly needed democratic overhaul of the UK state, to claim that it stood ‘for the many not the few’, and to convey the impression that education and health would flourish under its stewardship. Robin Blackburn argues that the half-measures promised by the new government are likely to whet the appetite for democratic reform and that, in economic and social policy, Labour will be driven either to disappoint its electorate or to invent new ways of mobilizing and directing the economy. He concludes that only a bold European ‘New Deal,’ and a willingness to work against the grain of economic ‘globalization’, can now overcome the great damage and division bequeathed by Conservative rule.”[26]

The quotation above is from the editorial intro to New Left Review after Blair’s victory in 1997. Sound familiar? It could have been written by the Left today.

Much of Corbynism can be chalked up to disgruntled Blairites. Blair had been their savior from the Tories and then betrayed them with the Iraq War. Corbyn, as then-chair of the Stop the War Coalition, represented the redemption of this sin by Labour, so that it could come to terms with itself, and all those activists who left in 2003 could come back. Corbyn is not really the “Old Labour” social democrat that Tony Benn was (and Benn himself was no Bevan). Unlike Benn, who was formed in the 50s and 60s, Corbyn is really a political product of the 80s and 90s, the neoliberal era, albeit through opposition.

So much of Corbyn’s sensibility about politics is reminiscent of Blair — even to the point of literally repeating Blair’s slogan, “For the many, not the few.” Corbyn has back-pedalled on his former opposition to nuclear weapons and NATO, betraying his so-called Left-wing foreign policy. He has replaced it in the 2019 election manifesto with the promise to launch an “inquiry” into the legacies of British colonialism. Such gestural politics were familiar to Blair, who “recognized” Britain’s role in the Irish potato famine and the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Corbyn’s move is a sop to his Millennial base, who have been brought up on such neoliberal gestural politics and plays to the PC identity politics they’ve learned at university. Such policies will play well with Corbynistas, but they will not attract back Labour’s former working-class voters, who do not have time for middle-class guilt and symbolism.

Corbyn’s most spectacular capitulation to the Blairites, whom he was supposed to defeat, was conceding to their demand for a second referendum on Brexit. This will not go down well in Labour’s so-called working-class heartlands either. The Left’s attempts to explain away working-class Tory voters with charges of racism or media bias recall the Democrats’ hysterical condemnation of Trump voters as “deplorables” and invocation of conspiratorial Russian meddling. Such explanations signal intellectual exhaustion and the end of the road.

Whether Corbyn loses this election to Boris Johnson, as most predict, or is able to muster a minority government with support from the Scottish National Party (SNP), it is clear that the Left will try to avoid its history in relation to the Labour party, and even more so the history of Marxism, in order to go on voting Labour, with or without misgivings. Elections have a weird generational impact, leaving people blinded to thinking critically about how capitalism is changing. We need to work against that tendency, to take a longer view and think critically. | P

[1] Audio recording: https://archive.org/details/Labour-Left-Platypus.

[2] Ephraim Carlebach, “‘Last illusions’: The Labour Party and the Left,” Platypus Review 97(June 2017), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2017/06/05/last-illusions-labour-party-left/>.First published as Ephraim Nashe, “Labour and the Left,” Weekly Worker 1146 (March 16, 2017), available online at: <https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1146/labour-and-the-left/>.

[3] See Chris Cutrone, “The Millennial Left is Dead,” Platypus Review 100 (October 2017), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2017/10/01/millennial-left-dead/>.

[4] Rob Sewell, “Don’t believe the polls or pessimists — we can win!” Socialist Appeal (November 22, 2019), available online at: <https://www.socialist.net/don-t-believe-the-polls-or-pessimists-we-can-win.htm>.

[5] Hillel Ticktin, “Confused Reformism,” Weekly Worker 1132 (November 24, 2016), available online at: < https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1132/confused-reformism/>.

[6] Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism (Zero Books 2009), p.78. See my article “Forgetting Mark Fisher,” Platypus Review 115 (April 2019), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2019/04/01/forgetting-mark-fisher/>.

[7] “Kinnock, Benn: No Choice," Workers Hammer 98 (May–June 1988), available online at: <https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/workershammer-uk/098_1988_05-06_workers-hammer.pdf>.

[8] From Fisher’s talk “All of this is temporary” at the CCI Collective.

[9] “Class War in the Labour Party," Workers Hammer 233 (Winter 2015–16), available online at: <https://www.icl-fi.org/english/wh/233/Labour.html>. Ultimately, they abandoned support for Corbyn after he revealed himself to be an “EU running dog.”

[10] Kinnock.

[11] Karl Marx, Capital, volume 1, Chapter Ten: The Working-Day.

[12] Theodore Rothstein, From Chartism to Labourism, Appendix: “1848 in England.”

[13] Ramsay MacDonald, Socialism and Society (1905).

[14] See Chris Cutrone, “The end of the Gilded Age: Discontents of the Second Industrial Revolution today,” Platypus Review 102 (December 2017–January 2018), available online at: < https://platypus1917.org/2017/12/02/end-gilded-age-discontents-second-industrial-revolution-today/>.

[15] Dora Montefiore, “On Burnley,” Justice, January 22, 1910.

[16] However, this was opposed on pacifist grounds by MacDonald.

[17] Lenin, “Speech On Affiliation To The British Labour Party,” August 6, 1920, Second Congress of the Communist International.

[18] Rosa Luxemburg, Reform or Revolution (1900).

[19] See my interview with Lawrence Parker, “‘Those Twenties’: An interview with Lawrence Parker on the National Left-Wing Movement,” Platypus Review 111 (November 2018), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2018/11/02/those-twenties-an-interview-with-lawrence-parker-on-the-national-left-wing-movement/>.

[20] See Mike MacNair, “In, out, shake it all about,” Weekly Worker 839 (February 27,2010), available online at: <https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/839/in-out-shake-it-all-about/>.

[21] “Future of the Labour Party,” Socialist Standard (December 1959).

[22] See Michael Fitzpatrick, “The fatal embrace of the Left and the Labour Party: Ralph Miliband’s changing positions on Labour,” Platypus Review 97 (June 2017), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2017/06/05/fatal-embrace-left-labour-party-ralph-milibands-changing-positions-labour/>.

[23] See my interview with Ian Birchall, “The unchanging core of Marxism,” Platypus Review 102 (December 2017–January 2018), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2017/12/02/unchanging-core-marxism-interview-ian-birchall/>.

[24] “We must fight against wage restraint,” Young Guard (October, 1963).

[25] Robert Borba, Judith Shapiro, Jack Conrad, and Hillel Ticktin, “50 years of 1968”, Platypus Review 105 (April 2018), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2018/04/01/50-years-of-1968/>.

[26] Editorial, New Left Review I, 223 (May/June 1997).