You don’t need a Marxist to know which way the wind blows: An interview with Mark Rudd

Spencer Leonard with Atiya Khan

Platypus Review 24 | June 2010

On Thursday March 11, 2010, Platypus Review Editor-in-Chief Spencer A. Leonard interviewed the prominent 1960s radical and last National Secretary of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), Mark Rudd, to discuss his recently published political memoir, Underground. In April, Leonard’s interview with Rudd, prepared in conjunction with Atiya Khan, was broadcast in two parts on “Radical Minds” on WHPK-FM 88.5 Chicago. Podcasts are available at the above link . Below is an edited transcript of the interview.

SL: I really appreciated the chapter on the SDS split in your recent book Underground. The kind of detail you go into there respecting the 1969 convention is rare. So, how would you characterize the ‘69 factional split within SDS in properly political terms—what were the parties and the lines of ideological fracture among them?

MR: My one-time ally and later opponent, Michael Klonsky, was the leader of a faction called the Revolutionary Youth Movement II. They had a slightly different line at the [last SDS conference in Chicago in 1969], but in the battle with Progressive Labor they were allied with us. In our conversation, Mike pointed out that the whole faction fight, the so-called split, happened among a very small number of people. Maybe a thousand members of SDS understood what it was about, whereas there were 99,000 more who had no idea. This faction fight between Progressive Labor on the one hand and the Revolutionary Youth Movement on the other was something happening among a very small group of people. The vast majority of both chapters and individuals in SDS were independent of the whole thing. Most were radicals in that they were opposed to the war, to racism, and, in some general way, to the system that gave us these things, though they might not have called themselves socialist. What we had in the split, however, was essentially a faction fight between different branches of Marxism-Leninism.

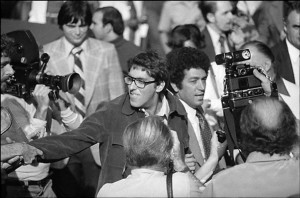

Surfacing from underground, Mark Rudd surrenders himself to the Manhattan District Attorney, September 14, 1977.

SL: This is what interests me. Of course, there is the mass student movement, but within it operates organized and ideologically driven politics.

MR: I just want to emphasize that this faction fight was hardly even understood by all members of SDS.

SL: Still, it has consequences even for those who do not understand it. That is the rub.

MR: There are a lot of rubs. We felt we were the heirs to the great tradition of 20th century revolutionary communism and that these battles—between [Che Guevara’s] foco theory and the primacy of national liberation, or between dogmatic Maoism and the primacy of the working class line—we felt that all of this stuff was extraordinarily important because it was the culmination of a century-long struggle that would end in the defeat and downfall of US imperialism and of the monopoly capitalism that undergirded it. We didn’t understand that we were really at the tail end of this whole business.

SL: One remarkable thing about the 1960s is that it was experienced as a kind of political high water mark and, for so many involved, a time of dramatic radicalization; however, when we look back, the 1960s seems more like the time when the Left entered into terminal decline.

MR: Yes. We made the fundamental mistake of believing that the war in Vietnam was the beginning of the end for US imperialism. We did not understand how deep American power went both economically and militarily. In retrospect, the military defeat in Vietnam was little more than a blip in the history of US imperialism. It was not the beginning of the end. Our group—which became Weatherman but which at the time of the split was known as Revolutionary Youth Movement I, adhering to what was called the Weatherman paper—thought that Che’s strategy was a prediction of the future, which was to “create two, three, many Vietnams.” We expected many more military defeats for US imperialism in the later part of the 20th century. We did not understand there was only one Vietnam which itself hardly mattered because the Vietnam War was not globally strategic. The Middle East, for example, is much more strategically located than is Southeast Asia. So yes, the United States was defeated militarily and forced to end its occupation of South Vietnam, but Vietnam never served as a model for any other revolution. In the 1980s, Noam Chomsky developed a line according to which the United States actually won the war in Vietnam in the sense that their only goal was to defeat a revolution that could serve as a model for others. After the United States completely destroyed North and South Vietnam, just devastating the country as a whole, then it could no longer serve as a model. Even though we and our puppet government in South Vietnam were forced out, even so we won the war because after that, nobody else wanted to get their country destroyed by the United States for attempting socialist revolution.

SL: And Chomsky’s thesis calls into question the triumphal image that the anti-war movement concocted for itself?

MR: I would differentiate between the anti-war movement and the anti-imperialist movement. In our case, we had discovered imperialism. When I got to Columbia University in 1965 David Gilbert was already talking about imperialism and leading a study within SDS. This work culminated in a pamphlet called “U.S. Imperialism” by David Gilbert and David Loud, through which we learned that the United States had engaged in innumerable interventions around the world and that Vietnam was just one of these. We also studied The Monthly Review, John Gerassi, and David Horowitz’s book Free World Colossus. The conclusion we drew was that national liberation movements throughout the world and, internally, within the United States were actually poised to defeat American imperialism. That understanding became the ideological basis of the Weatherman faction.

SL: I want to return to this and to the kind of “Marxism-Leninism” it represented. But first, I would like to take us back a bit. In Underground you discuss the roots of the split within SDS nationally and within your own chapter at Columbia. There you show how the split at Columbia was not isolated, but paralleled splits taking place on other campuses. I am interested in your perspective on the split within the chapter at Columbia between what was known as the Praxis Axis (which I understand to be more of an organization-building and consciousness-raising politics) and your own Action Faction.

MR: Here you are talking about a split among the SDS regulars. There was also a split between the regulars and the Progressive Labor Party which was ultimately reproduced in the split at the last national convention of SDS in June of 1969.

Among the SDS regulars at Columbia there were two tendencies. The Praxis Axis was composed primarily of older graduate students and people who oftentimes were red diaper babies, i.e. they were children of communists, socialists, and labor people. They had an organizing perspective according to which you build your base over a long period of time and, if everything turns out well, you will eventually have enough strength to act. It might be more accurate to call this a base-building or organizing tendency. And then along came kids like myself. Influenced by Cuba, we seized upon the idea that action galvanized mass support. This was kind of backwards in one way and vanguardist in another. It was backwards according to the organizing model of building a base first. But I must have sensed intuitively the potential of that spring of 1968 at Columbia after the Tet Offensive, the abdication of LBJ, and the assassination of Martin Luther King, because the base was already built. A lot of people at that time began to reconsider their own relationship to the war and to racism, so that when a few people acted, support appeared as if out of nowhere. So, what started with the demonstration of about 150 people at the end of March grew by April 23rd to 500 people. Then, with the occupation [of a campus building] the next day that support mushroomed to over a thousand people in the buildings. By taking action we took advantage of the support that had been developed through years of organizing.

SL: But, at that time, the success of the dramatic building occupations was viewed as a vindication of your Action Faction’s tactics over those of the Praxis Axis. But now you are saying that this was a misreading of the situation, because it was really their tactics that were responsible for the success of your actions.

MR: Yes. Militancy and confrontation maybe could be thought of as a strategy, but basically it was a series of confrontational tactics. The overall strategy was education plus confrontation plus personal relationship-building. But at the time we misread it completely. We took the Columbia Revolt of April and May 1968 to be a vindication of Che’s foco theory (i.e. the theory that a small group takes action and the masses join in once they see that guerilla warfare can work). That was a theory promulgated by the Cuban Communist Party in 1967 and 1968 and we lapped it up. Our Action Faction tendency and mentality fit in with the foco theory. At one point I made a speech quoted by Todd Gitlin in his book[1] in which I am reported as saying, “organizing is another word for going slow.” I did not want organizing. I wanted speed and confrontation and militancy. After Columbia, however, almost every single application of this non-strategy of confrontation and militancy resulted in defeat and failed to build the movement.

SL: But it was the perception that those tactics had succeeded that catapulted you to a position of national leadership in SDS in 1968?

MR: Absolutely. It is bizarre but it has resonances and echoes even now, forty years later. No amount of actual testing of the ideas could deter us from believing that we were right. For example, in June of 1969, after the last national convention, when I was elected national secretary and Weatherman took over the SDS National Office as well as some regional offices, we called for an action in Chicago. We called it the National Action but later the press called it “Days of Rage” and the name stuck. In June we had about 500 people organizing for the Days of Rage, but when the time came only about 300 people showed up. But we just blew off the experience of going from 500 down to 300. We said to ourselves, “oh well, what we are doing is right. It is very tough to find people who will actually take on fighting the state and building a revolutionary army, so our small numbers only mean that we are right and we have to keep going.” You would think the fact that we had de-organized from 500 down to 300 would have told us something. The problem was idealism: We thought that our ideas were right and we held to those ideas, despite the fact that the only proof we had of our ideas was that we held them.

But everybody was idealist. Klonsky’s Revolutionary Youth Movement II went to the workers to build a revolutionary communist party and some people spent 10 or 20 years doing that only to have nothing come of it. Similarly, the Maoist Progressive Labor Party sought to build the worker-student alliance by uniting students with workers, because “ultimately the workers will make the revolution,” because “it’s a class question,” and because “the proletariat is the revolutionary class in society.” How did they know? Marx and Engels wrote it in 1848. Then there was the idea that the Black Panthers were the revolutionary vanguard. How did we know this? SDS said so. But what was our proof? Well, there has to be a vanguard and they were talking about revolution, picking up the gun, and chanting “Off the pig!” That must make them truly revolutionary.

Of course, the right wing has its own form of idealism. They say, “the United States is the greatest power the world has ever seen and can impose its view on the world.” No amount of data can prove such a claim. So now it is seven years later and we are embroiled in two wars, both based on right-wing idealism.

SL: But theoretical differences, such as they were, were nevertheless at the heart of the factional struggles inside SDS. Here you are dismissing all ideology as

“idealism.” But is not “idealism” of this sort unavoidable, even necessary, especially on the Left?

MR: Well, it is and it is not. For example, Marxism has been so discredited now by the 21st century that there are only a tiny handful of young Marxists. The dominant ideology is anarchism among students and young activists. They are anti-state, of course, but in terms of strategy everything is reduced to self-expression, the need to express opposition to the state by wearing bandanas, breaking windows, and fighting cops.

SL: When you see these young anarchists, to what extent do you see them as your political offspring? How much do you find them romanticizing you and Weatherman in ways that you now find uncomfortable?

MR: It makes me very uncomfortable. The only value of the Weather Underground, it seems to me, is to learn what not to do. So when I see people making the same damn mistake, it upsets me. Last week I was in Pittsburgh and was arguing with some young people there who were involved in the G20 demonstrations back in September. They were a tiny faction of the six or eight thousand people there. About 200 of them wanted to march without a permit. They wanted to wear bandanas, and to show their militancy. They would not abide by the general agreement of nonviolence. So what I see is the need these people have to express their opposition rather than to think strategically about what will build the movement. This is the error we made. We went from organizing, which was essentially what built Columbia SDS, to swallowing an entire theoretical framework about revolution and anti-imperialism, militancy and support for the Third World, revolutionary solidarity, etc., all of which we took in the direction of self-expression. With the Days of Rage we believed that if by fighting the cops we showed people how militant and serious we were they would join us. But that does not build a movement. Today’s anarchists are making the same mistake.

SL: What type of organizing did SDS engage in when you first joined the organization? How did it differ?

MR: It was talk. It was relation-building. It involved education. It involved engagement with people who did not think like us, but might be won over. So we would sit down and talk and find out what they thought about the war in Vietnam or about racism and tell them what we thought to see if there was any common ground. Such organizing took place over a long period of time—I am talking two to four years—and it paid off in the April 1968 confrontation. For instance, when I was a freshman at Columbia, studying in my dorm, David Gilbert, who was a senior and the chairman of the Independent Committee on Vietnam, a predecessor of the Columbia SDS chapter, comes knocking on my door. He was out organizing dorms, talking with people about the war and about racism.

Every day SDS had a table set up on campus. People would walk by and we would engage them in discussion about the war. I recently ran into somebody who remembers the brilliant arguments David made debating a ROTC guy in front of the SDS table. There was a lot of engagement with people rather than mere demonstrations of how deeply we felt about the war.

SL: So if we think about that in terms of its historical roots, some people in SDS were red diaper babies who inherited notions of base-building organization from the Communist Party. There were also streams coming out of the labor movement. So, to what extent do you think that these organizational strategies that people were improvising in SDS in the mid-1960s were actually new?

MR: We were the direct heirs of the Civil Rights and labor movement. The model for organizing came to us directly from those movements. The graduate students at Columbia had been in the south with SNCC, for example, and had learned organizing with Miss Ella Baker in Mississippi. To the extent that the anti-war movement grew, it was because of this organizing. I think that the mistake was believing after the Columbia Revolt that our self-expression politics, our confrontational politics, our hyper-militancy was what won people over. Certainly after Columbia it all failed. So my book is really the story of good organizing, SDS, followed by bad organizing, Weatherman, followed by no organizing at all, the Weather Underground. A friend of mine calls the Weather Underground “existential politics.” A bomb here and a bomb there—this was our form of self-expression.

What I have discovered in the last few years talking with students on college campuses is that, however well intentioned, they have no conception of organizing. They think the anti-Vietnam War movement happened spontaneously. It was a good idea so people came together and protested. They have never heard of SNCC or Ella Baker, and have scarcely heard of Saul Alinsky. They have no notion that a movement must have a growth strategy. When in the March of 2003 millions of people went out to the streets, they thought this would stop the war. After all, they had demonstrated their feelings on the subject. But that is not what a movement is. Historically, that is not what built all the great social and political movements in this country. For that, one must look to the secret American tradition, the one of real organizing.

I find that young people are trying to get back to that tradition and to figure it out. They are reading Barbara Ransby’s excellent Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement or Charles M. Payne’s I’ve Got the Light of Freedom about SNCC’s operations in one town in Mississippi, to which Payne returns to talk to everybody who was involved to discover what was their method of organizing? The answer Payne gives is that it had to do with building strong relationships and leadership development at the base level. SNCC adapted this model from the practices of Southern black churches. It was led by women and was highly democratic. This is stuff that needs rediscovering. I have dedicated myself to helping people figure this stuff out now.

SL: On the subject of the Civil Rights Movement, the New Left was, so to speak, galvanized by that struggle and yet still, at the time of your politicization in 1965 the student left, including SDS, remained tacitly divided along racial lines. This strikes me as very bizarre, this whole idea of the white left and the black left. Why wasn’t the Left already integrated? And since it wasn’t, why was this not a primary goal in the second half of the 1960s?

MR: The Black Power movement that emerged from the Civil Rights Movement, specifically from SNCC, hit organizations like SDS very hard. It was very difficult to understand how to function within this new idea of black self-determination and black separatism. It was like a punch to the gut. At the same time, it was very radical. We knew we had to understand Black Power. We could not whine, off on the sideline, and say “gee, all we want is an integrated organization and non-violence.” We had to understand what they were saying. They could not function in the same organization with white people because white people dominated because of internalized superiority or racism. The critique that Black Power made was enormous and, in a way, it drove us over the edge. This was especially true with the Black Panthers, because they seemed as if they were solving the problem for us by being both a Black Power organization and socialist. They recognized that there was both a class aspect and a racial aspect to oppression. So white leftists jumped on the Black Panthers’ bandwagon as a group we could ally with and work with. Meanwhile, the Panthers were getting smashed by the police and by the feds, murdered, literally murdered, and they needed support. So we served a function for them. This was especially true because the base they had built up in places like Oakland and Chicago, and to some extent New York, was evaporating. Black people didn’t want to die and to be involved with the Panthers was almost suicidal. In fact, that was the title of Huey P. Newton’s autobiography, Revolutionary Suicide. Running around with guns and chanting “Off the pig!” meant that the feds and the local police were going to kill you. And that’s what happened.

SL: So is it fair to say you inherited this split, derived from the Civil Rights Movement’s failure to radically transform American society through integration?

MR: No. It seemed to us that integration was played out. Black Power superseded both it and non-violence. The Black Power elements were much more radical in understanding the depth of the system, the depravity of the system, and in demanding self-determination. We wanted to be out there with them and the way to do this was to adopt a “revolutionary solidarity” line. This is what became the justification for the Weather Underground: We were to be a white fighting force in support of black revolution. To this day some of my old comrades still believe in this.

This is something rarely discussed anymore. Certainly, it hasn’t been analyzed. Still it is rare to find anyone who critiques Black Power or the implications of the slogan, “By any means necessary!” I now feel that non-violence was not at all played out. People were tired of getting attacked by the police and by racists and there was a desire to fight back, but the approach taken by the Panthers was ultimately a losing strategy.

SL: Did you read Harold Cruse’s Crisis of the Negro Intellectual when it came out?

MR: I did not, but I should have.

SL: That book, which emerged out of Harlem in 1967, criticized both the limitations of the integrationist movement and black nationalism. It viewed the latter as an unfortunate symptom of failure, not as a way forward. You’re saying that, retrospectively at least, you’re sympathetic to that view?

MR: Was Black Power a winning strategy?

SL: No. I agree that black nationalism was a dead end for the left. But it is remarkable to hear you saying it.

MR: When I say this publicly people scream, “Racist!”

SL: Let’s go back and talk more about what Marxism meant to the Weather Underground. How did this ideology concocted from equal parts Regis Debray, Che Guevara, and Ho Chi Minh represent a form of Marxism? What sort of emancipation from, or analysis of, capitalism did it offer? After all, one can think of Marxism as a politics of the working-class in the core capitalist countries; but you guys completely turned that on its head so that national liberation and the defeat of racism became the primary content of the terms

“freedom” and “emancipation,” or even “socialism.” Beyond the defeat of American racism and imperialism, did socialism as you understood it really involve any fundamental transformation?

MR: For us, white skin privilege translated into American national privilege, so that all Americans were privileged economically because of the empire, which is true, incidentally. Almost the poorest person here lives better than most people in Africa. The depredations of capitalism have been exported to the Third World; the two-dollar-a-day wage shows up in our cheap goods at Wal-Mart. So, I do not think that what we were saying is totally wrong. On the other hand, we have to finance and produce manpower for wars to keep the thing going. So, there is tremendous stress and exploitation that takes place at home because of the militarist system.

But there is no simple remedy to this problem. Whether you think the Third World is going to bring down imperialism or you think workers in the United States are going to bring down imperialism, none of it works. It is all in the realm of idealism or even religion. Marxism is very nice as a tool with which to analyze the workings of a class society and I think that we could use a little bit more of it to understand stuff like the current economic meltdown. But if we want to know what is going to happen, Marxism doesn’t work. The Third World did not rise up against US imperialism. The workers have nowhere risen up against the capitalist class. I have become anti-ideological. We just have to muddle along.

SL: To me, calling national liberation in the Third World and decolonization the realization of leftist political aims seems almost a mockery when we look at the prevailing poverty, degradation, and political corruption.

MR: The corruption especially. Vijay Prashad in his book, The Darker Nations, provides a fabulous analysis of the defeat of national liberation at the hands of the new elite that rose up everywhere. National liberation as the antidote to imperialism was an illusion. I have friends who died for this illusion and other friends who are in prison for it, probably for the rest of their lives. Some are still fully committed to the illusion of national liberation. I hate to tell you this, but I am a liberal democrat.

SL: If what liberal democrats do is critically reflect on political experience, then I am all for them. As regards the 1960s, one just hears the usual, “Well, the man was too big and too strong, but we tried our best.” If we try to think the full depth of this problem, we have to ask ourselves, How we can imagine leftist politics as ever leading to anything but despair and disillusionment?

MR: I have been thinking a lot about this and have come to the conclusion that there is a potential progressive majority in this country, but only a progressive majority and not a revolutionary one. It has to be organized around simple ideas like the government as the embodiment of the national collectivity that has some responsibility for people, for the wellbeing of people and of the planet. This is simple, 18th century liberal stuff. Now what we have is a complete and total political and ideological victory of free market individualism and militarism. We have to combat it with the notion that there is such a thing as the collectivity and that the government has a responsibility for the wellbeing of people and of the planet. That is about as far as I can go.

SL: In the German context, when the student movement emerged there in the 1960s, the Marxist intellectual Theodor Adorno called into question the movement’s leftist character and said, in essence, “These young people really seek only the narcissistic satisfaction to be achieved by direct action. They are not really interested in or capable of transforming the circumstances that generate the discontent.” He thus took a critical position against what he saw as the authoritarianism rampant on the New Left in Europe. To what extent do you think authoritarianism was a factor both in your own particular political experience and on the American left as a whole in the 1960s?

MR: I think the popularity of Marxism-Leninism is a good gauge of that. Marxism-Leninism is essentially an authoritarian organizational strategy. It says, “Our little group knows best. We have the truth and we are going to impose it on everybody.” And of course, the New Left wound up in the 1970s as a giant mix of Marxist-Leninist groupuscules. There is the authoritarian tendency, the idea that we know best about everything. To me it is reappearing in the kids in Pittsburgh who want to wear bandanas and march without a permit. They said, “Well, we know better than everybody else because we have the truth. We understand how terrible the system is. You are just a liberal and don’t understand.”

SL: What about the exclusive preoccupation with action? To my mind, this is what historically ties today’s anarchists to the Weathermen. In both cases reflection has determined that the problem is reflection. It is almost a theoretical anti-theory, or an intellectual anti-intellectualism.

MR: That could be, but that was not our problem. Our problem was too much of both, too much belief in the propaganda of the deed and too much belief that national liberation was going to defeat US imperialism. So we had the worst of both worlds. We had the action plus the ideology. There has to be some way of testing the truth of ideas. The best I can figure out is growth of the movement, numbers. If you count how many people are at a demonstration and then, a year later, you count again and discover that your numbers have gone up, you are probably on the right track. If they have not, you are probably not.

SL: How do you know that the movement that is growing is the movement you want?

MR: You don’t. Nobody can know. You just blunder along. That is why I am for non-violence, because at least you are adopting strategies and tactics that do not do irreversible damage. In my experience, almost everything I ever did that I thought it was going to turn out one way turned out another. That is why I am a liberal, because hopefully liberals kill fewer people than radicals. I am for nobody killing anybody else, and that includes governments, terrorists, and communists, though, of course, there are not that many of those left in the world anymore. |P

Transcribed by Brian Worley

[1]. Todd Gitlin, The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage (New York: Bantam Books, 1987).