1933

The Decline of the Left in the 20th Century

Toward a Theory of Historical Regression

Platypus Review 17 | November 2009

On April 18, 2009, the Platypus Affiliated Society conducted the following panel discussion at the Left Forum Conference at Pace University in New York City. The panel was organized around four significant moments in the progressive separation of theory and practice over the course of the 20th century: 2001 (Spencer A. Leonard), 1968 (Atiya Khan), 1933 (Richard Rubin), and 1917 (Chris Cutrone). The following is an edited transcript of the introduction to the panel by Benjamin Blumberg, the panelists’ prepared statements, and the Q&A session that followed. The Platypus Review encourages interested readers to view the complete video recording of the event, available at the link above.

1933

Richard Rubin

THE DATE PROPOSED for me to discuss, 1933, immediately summons up two names: Roosevelt and Hitler—Reformism or Barbarism. I wish, though, to couple them with another pair, and another date. The date is 1940. The names are Trotsky and Benjamin. These four names are meant both as contrasts and parallels. At first glance, Hitler and Roosevelt, the New Deal and fascism, might seem polar opposites. But, as Wolfgang Schivelbusch points out, many contemporaries understood Roosevelt and fascism as addressing comparable problems, albeit by somewhat different methods. Similarly, while Benjamin the melancholic mandarin and Trotsky the fiery revolutionary might seem at opposite poles of Marxist discourse, it is the thesis of Platypus that they are both responses to the same crisis of Marxism, just as Hitler and Roosevelt are responses to the crisis of capitalism. These two crises, the crisis of capitalism and the crisis of Marxism, have determined the history of the 20th century, and continue to weigh on the history of the 21st.

These two pairs are also linked by the dates of their deaths: Hitler and Roosevelt in 1945, Trotsky and Benjamin in 1940. While such facts are, in one sense, mere accidents, they can also be read as signs. A generation may be linked by the date of its death as well as its birth.

Trotsky speaking to the Danish Social Democratic student group in Copenhagen, 1932.

Two Marxist refugees with great literary talents, two men who experienced “a planet without a visa,” both Trotsky and Benjamin were of a type that was common among many Jews in the first half of the 20th century, before the great caesura of the Holocaust and the State of Israel intervened: men of a deep cosmopolitanism that is almost unimaginable today.They were both men who, despite everything that had happened by the mid-20thcentury, still seemed rooted in the earlier, less bleak beginning of the century. They are of their time, but also out of their time, figures um neunzehnhundert [“circa 1900”]. Their unnatural deaths seem to anticipate a new and incomprehensibly horrible world; Auschwitz and Hiroshima are around the corner, yet they just miss them. It is as hard to imagine them in the postwar world as it is to imagine Voltaire and Rousseau living on into the world after the French Revolution. They prefigure, and therefore do not pass beyond. If, as Adorno famously stated, after Auschwitz it will be forbidden to write poetry, they are spared, by the time of their deaths, from the burden of this prohibition. They are two fragments of the unfulfilled, secret counter-history of the 20th century—the history that remains actual, by virtue of its unfulfilled potential.

By contrast, Roosevelt and Hitler are the so-called “real” history of the 20th century. If Trotsky and Benjamin speak to the utopian possibilities that remain hidden away in capitalist society, waiting to be unlocked, Hitler and Roosevelt speak, by contrast, to the barbarism that lurks underneath the veneer of bourgeois society, on the one hand, and on the other, to the supposedly “realistic” limits to which we can hope to aspire for a better society. In the end, Roosevelt played the “good cop” to Hitler’s “bad cop.” It says everything about the poverty of our moment that, in the midst of the greatest capitalist crisis since the 1930s, the highest aspiration of most of the Left is Roosevelt, as evident by the increasingly common question, Will Obama be another FDR? From fantasies of neo-conservative “fascism” a few years ago, much of the Left has moved effortlessly into fantasies of a new Popular Front. But, of course, the obvious is avoided: There is no socialist threat for Obama to head off. On the contrary, protests against the bailouts take the form of an inchoate populism. AIG and “greed,” not capitalism, are the targets.

Similarly, if the avowed neo-conservative aim of “spreading democracy” is ideological eyewash, one must also admit that the chief targets of US imperialism are no longer primarily the Left, as during the Cold War. On the contrary, the “wars of empire” are now wars against extreme right-wing forces, as in Afghanistan—right-wing forces that themselves bear more than a passing resemblance to fascism. But this inchoate quasi-fascism is as unlike the world-threatening grand fascism of the 1930s and 1940s as it is unlike the Che Guevaras of the 1960s. Within the metropolitan Left, “anti-fascist” and “anti-imperialist” impulses clash over the problem, and leave only muddle.

Thus, if the Obama administration goes to “war” with Somali pirates, for example, some on the Left will surely feel obliged to express solidarity with the pirates. We will be told that Empires are really pirates writ large, et cetera. No one believes, of course, that piracy is really socialism—but, lacking socialism, we feel that we must make do with piracy, and label it a form of “resistance.” The sheer misery of the present cannot be confronted head-on. To use a phrase invented by Robert Musil, “Seinesgleichen geschieht” [“The like of it now happens,” or “Pseudo-reality prevails”]. Pseudo-reality prevails in a world of pseudo-politics. Something like reality is happening, but it is not really real. We sense this, but are unsure how to talk about it. We try to ignore what we know. We seek historical mirrors, but, like a house with a corpse in it, we find that the mirrors have all been covered over.

But how did we get here from the world of 1940? For, in 1940, the world was not as miserably depoliticized a place as it is today. It was a tragic and frightening place,indeed, but still tragically and frighteningly real. The difference of course is not in “the world,” but rather in our ability to understand it. The central meaning of“regression” is this: Increasingly, the Left does not address the world but rather its own unresolved history. One should not imagine defeat as something merely imposed on the Left by the right, by mere superior force; rather, defeat has been deeply internalized on the Left by ways of thinking, the goal of which is self-censorship. In particular, two crucial periods must be constantly reenacted and misunderstood: the 1930s and the 1960s. These are not high-points or models—we must now construct neither a new “New Left” nor a new “Old Left.” Instead, they are both crucial stages in the long disintegration of the Left. The period 1933–1940 is the last attempt of classical Marxism to rearm itself against the double menace of Stalinism and fascism. Trotsky represents the central figure in this struggle. Trotsky was the last of the Second International radicals, and, with him, the history of classical Marxism ends.

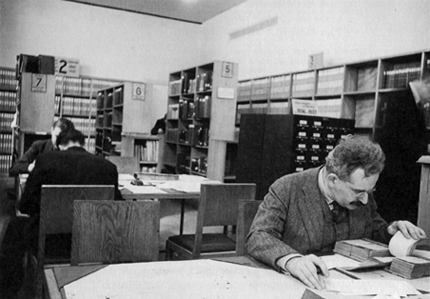

Benjamin working in the Bibliothèque National, 1939

This was simultaneously the source of Trotsky’s greatness and his limitation. By contrast, the Frankfurt School, while politically less clear than Trotsky, saw other things perhaps more clearly. One might say that Trotsky understood Stalinism better, and the Frankfurt School understood fascism better. In the end, however, both Trotskyism and the Frankfurt School survived only as standing challenges. Neither would prove intellectually creative in the postwar world. At most one could only hold one’s ground. In the end, Adorno remained a lonely figure and the Trotskyists—all 31 flavors—were, even in their own estimation, mere epigones. Indeed, the best Trotskyists would insist that, in over two-thirds of a century since Trotsky’s death, there has been hardly anything deserving the name of Marxist theory. While scandalous, this is probably true. If we are to take Marxism seriously, the central task of any Marxist theorist now is to try to answer the question, Why we do not have an adequate Marxist theory of the present?

But if the 1930s were the tragedy, that is, an actual defeat, and the 1960s were the farce, that is, a defeat acted out before actual combat could be engaged, what needs to be understood is the bridge. The 1960s would repeat the 1930s in many ways, without understanding them. Hence, for example, the paradox of Maoism—a rebellion of sorts against Stalinism that was and is itself hyper-Stalinist.

Afterwards, the compulsion to repetition would set in, and there would be an even further evacuation of political meaning. The peace movement never dies, but that is merely because it never wins, nor even needs to reflect on its goals. There will always be war. We can always be “United for Peace and Justice,” can’t we? There will always be something to “resist.” Infinite, never-ending “struggle”—or the simulacrum of struggle—is all that matters. Struggle has become a symptom, not a means. One can no longer even counterpose reform and revolution; increasingly, the Left has ceased to believe in either. Both involve questions of power, and how can a powerless Left dare to think about power? Instead one is sustained by a myth: the myth of the 1960s.

For many decades, it seemed as if the waiting for the 1960s to return would never end. But, in the last year, the Zeitgeist has finally begun to change. On the one hand, the election of Obama, a black man who is a post-boomer, unsettlingly conservative, and unsettlingly popular with White America, and on the other, a real economic disaster that brings back all of those good Zusammenbruchstheorie [“Crisis Theory”] moments we thought we had lost. Finally, even the Left is starting to realize the 1960s are dead. But now we are waiting for the 1930s. Identity politics is passé, yet only in that “class” is the new “black.”

The problem, of course, is that we have been here before. For example, some may remember in the 1970s a “turn to the working class” by remnants of the New Left, which had only a few years earlier written off the working class. But even more to the point, the 1930s were a decade of defeat for the Left. The last thing we need is to revisit 1933! The myth of the 1930s is the flipside of the myth of the 1960s. It is precisely because the real but belated possibility of revolutionary politics was defeated in the 1930s that it took on a spectral and confused form in the 1960s, and it is the inability of leftists since the 1960s to overcome the notion that the 1960s represented a higher, better form of politics—that the so-called “New” Left had left the “Old” Left behind—that is the main reason for the nearly total obsolescence and irrelevance of the Left today. Neither the 1960s nor the 1930s offer models for a future Left, unless they are recognized as the two-fold trauma that the Left needs to overcome.

That, at any rate, is the Platypus thesis of regression in a nutshell. Is this a hopelessly pessimistic view? Certainly, it does not partake of Trotsky’s revolutionary optimism. The optimism of classical Marxism was once historically justified, but now, alas, is not. In this respect, Platypus is certainly closer to a Benjamin than a Trotsky. But we in Platypus believe that ours is a hopefully pessimistic view. We continue to hope that it is by an accurate recognition of its own defeatism that there is still time for the Left to reconstruct itself and create a future for human freedom. We reject a fake optimism, precisely because we continue to hope—and a false optimism is the deadly enemy of true hope. In answer to Nietzsche’s question, “Gibt es einen Pessimismus der Staerke?” [“Is there a pessimism of the strong?”], we answer: “Yes!” |P