The Black Belt thesis: An interview with Timothy V. Johnson

Daniel Deweese

Platypus Review 143 | February 2022

Daniel Deweese of the Platypus Affiliated Society conducted an interview on November 20, 2021 with Timothy V. Johnson, author of “‘Death for Negro Lynching!’: The Communist Party, USA's Position on the African American Question” (2008). What follows is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Daniel Deweese: Could you say a little about your political history? What motivated your interest in the history of American communism and its relation to the black struggle?

Timothy Johnson: I've been involved in the Left and particularly in the African American movement since I was a teenager in high school. I was involved in organizing around various community issues. Most people my age — I'm 69 — were first radicalized by Malcolm X. I remember reading, when I was beginning high school, Malcolm X's autobiography, and an article that appeared in the magazine Sepia, which was a low rent version of Ebony magazine. There was a line in Sepia that said something to the effect of, even though Malcolm X was a racist, he was not racist in his readings and two of his most liked authors were Karl Marx and Immanuel Kant, two people I had never heard of, so I went to the high school library and asked if they have anything by Immanuel Kant. The librarian brought me the Critique of Pure Reason, which I read, but it didn't have anything relevant to what I was interested in at the time. I went back later and said, “have you got anything by Karl Marx?”, and the only thing they had was a copy of Capital, which I read, and it made sense. If people approach it just as a regular book instead of some real involved theoretical piece, it's much more readily understandable. This was around the time the Black Panther Party was beginning. I read something by them, and they said that they were Marxist-Leninist, and I thought “this is an interesting organization”. I did some work with them around the Ohio area, went to college, and lived in several different cities involved in various kinds of work, but mostly smaller collectives in any given city, mostly based in the African American community and most self-identifying as a Marxist or Marxist-Leninist. In the early 1980s, I joined the Communist Party and worked for the newspaper in California, which is the People's World, which then merged into the People's Daily World on the East Coast. I was a reporter in Los Angeles for a year or so, and then moved to New York to edit the paper's magazine section.

DD: What was the Black Belt thesis?

TJ: The Black Belt thesis was essentially a result of a newly developed communist movement trying to come to terms with how to approach the question of racism and African American oppression theoretically. Of course, they unfortunately were burdened by the Socialist Party's approach, because most of the people in the newly founded Communist Party in 1919 came out of the socialist movement, and the socialist movement had a varied approach. On the one hand, some people thought that the struggle against racism was an important part of the class struggle. On the other hand, you had people that were essentially racist and saw no need to address this issue. A large group of people in the middle said, we need to talk about the question of racism, but we do not need a specific program because, primarily, we do not want to alienate white workers. That was pretty much the Socialist Party position in the South, where they said, if we say anything that speaks towards the equality of African Americans, we are automatically going to lose all the white socialists in the South and a large number of white socialists in the North.

The Socialist Party never came out with a concrete program and essentially considered the issue of African Americans just to be a racial question that will be resolved after the working class seizes power. And then after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 and the development of the Communist International (Comintern), the newly formed communist movement around the world began to develop positions on what they called the national question, which essentially came out of how to deal with the question of oppressed nationalities in Europe, specifically in Russia, given that is where the revolution took place. At one point, Lenin referred to Russia as a prison of nations, referring to all the various national groupings oppressed by the Russian czar. In some of his other writings, Lenin also referred to African Americans as an oppressed nation. However, he had not done a lot of detailed study of this. It was based on some of the things he had read, so members of the Communist International took the newly formed American Communist Party to task for not having a specific program. Again, because most of those new communist organizations were relying a lot on the theoretical heritage of the Socialist Party, it was considered a racial question. However, they were more advanced than the Socialist Party, in the sense that they took up the importance of struggling against racism and inequality. They just saw it as all subsumed within the general working-class movement.

In the various Communist Party meetings, conferences of the Communist International, particularly the third through the seventh meetings of the Comintern, they spent a lot of time trying to deal with the African American question, but that was also just a sub-part of the broader national question and colonial questions in Africa and Asia, etc. Within the Comintern were three non-American communists who had lived in the United States. One was Sen Katayama, a famous Japanese communist who spent several years living in the South and was knowledgeable about segregation and racism. Second was M. N. Roy, a Bengali communist, who had spent several years in the United States. Third, was Michael Nassanoff who early on had been elected to a top position in the Young Communist International and lived in the United States for at least a year, maybe longer. In addition to that, you had several African Americans who were there attending the [International] Lenin School. This included Harry Haywood and several other people. Those people got together and pressed the U.S. Communist Party to develop a more sophisticated position. They found that the best framework to address the issue is through the framework of the national question. This is also referred to in some of Lenin’s writings, although not in detail.

There had been a number of communists who looked at the area of the South, where African Americans were the majority of the population, yet had virtually no political, legal rights to anything. By and large, they were sharecroppers, with minimal land ownership. Essentially they said that the Communist Party should have a two-prong position. Within the Black Belt — they carved it out of a map looking at counties and their racial percentages, or nationality percentages, to look at the majority area — so then within the areas that were majority African American, those people have the right to either form a separate state within the United States, form some kind of affiliation with the United States, or independence. The slogan was never “independence for the Black Belt” or anything like that. It was always self-determination, meaning those people in that area had the right to determine their affiliation. For African Americans in other parts of the country, the party’s position was one of full political, economic, and social equality.

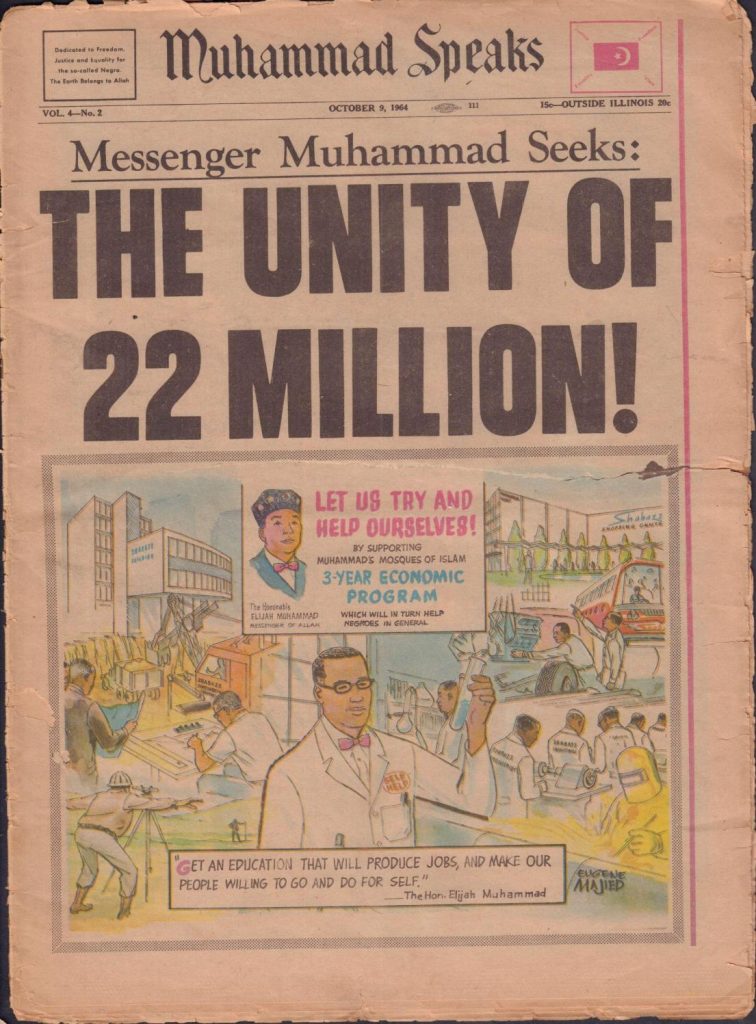

In that period, adopting that position led to the U.S. Communist Party's greatest organizing of any group on the Left in the African American community. Within that context, they took up the issue of the Scottsboro defendants and turned that into an international issue. They took up cases of lynching and turned those into international issues at the same time in the North. They fought for voting rights, for housing, non-discrimination, employment non-discrimination, for the unions being open to African American workers, and for unions taking positions against racism. An interesting side note is that even though this kind of Black Belt theory originated through the Communist International, U.S. communists, and communists from other parts of the world, it is also something that has always captured the imagination of the African American movement. Particularly the nationalists, because a little after the party announced the position of self-determination for the Black Belt, the Nation of Islam, led by Elijah Muhammad, started in Detroit where the party had a heavy presence. Their position was, essentially, this is the black nation, and if you ever look at Muhammad Speaks, which used to be the name of their paper, one of their demands was X number of states in the South, where black people are majority, and that was directly taken from the Communist Party and the Comintern position.

Much later in the 1960s, there was another organization called The Republic of New Africa. They were started by a mixture of nationalist and Left-nationalist African Americans. They too had the same position of taking five or six states in the South where black people were a large portion of the population, and that being turned into a separate black nation, which they called the Republic of New Africa. It was something that caught on. Its immediate significance, as I said, is it spurred the party to not look at the oppression of African Americans as a racial question, whatever that might mean, but to look at it under the rubric of a national question, which was taken up in places around the world based on the significance of using that category. If you look through the Party documents from that time, it was a struggle within the movement. This is not something that just came down from the Comintern and was accepted by the Party. There were fights and struggles within the Party to get them to adopt that position and to get them to see the significance of the African American struggle. If you look at documents sent out for May Day annual demonstrations — the documents coming out of the national headquarters in New York — they said, “You must emphasize the right of black people in the Black Belt to determine their own destiny.”

The Party emphasized complete, not just political and economic equality, but social equality, because there were some racist elements who were willing, grudgingly, to accept political and economic equality, but not social equality and integration. They did not want interracial marriage or any kind of interracial social mixing in a sense, so the Party had to fight a struggle within its ranks to the extent that it became something that the Communist Party was known for. It was an organization that would not compromise at all on the question of the complete equality of African Americans, so much so that when the Civil Rights Movement began in the 1960s, immediately white racists in the South said it was a communist plot. Because they encountered this in the 30s, when the only people down there talking about racial equality were communists. Then you have these young people and SNCC coming down here; these people must be communists. That's the kind of psychological impression that it had.

The Communist Party itself began to evolve its position, particularly as you had [black] migration from the South with the development of the economy’s manufacturing industries in the North. Because of increasing mechanization in the South, there was less room for sharecroppers and tenant farmers, and people wanted to get out of the fascist-like atmosphere that existed in the South. It became known as the Great Migration, which began in the 20s and 30s, and then ended in the 60s. That was part of it. The other part of it was the Popular Front, which limited the militancy of the movement to build a broader progressive movement due to the threat of fascism. So, essentially Earl Browder, who was the head of the Communist Party, began to question whether self-determination for the Black Belt was the correct position. Browder had a lot of other strange positions too, and eventually, he was demoted and expelled from the Communist Party. After they got rid of Browder, they brought self-determination back, but that led to a five- or six-year discussion on the Party's position on the Black Belt which ended in the 50s. It was summarized by Jim Jackson, an African American leader of the Communist Party, who had organized in the South and Detroit for much of his political life. His bottom line was that it is clear that the African American question is a national question — but a national question of what type and of what solution? Essentially he came to say that what the Party has support for is not self-determination for the Black Belt, but political, social, and economic equality, and the Party has to fight for the centrality of the position of African American equality within the context of the class struggle and within the context of the broader democratic movement. That has been roughly the position of the Communist Party since that time in the 50s.

DD: You have previously described Eugene Debs's position as a “centrist,” one within the Socialist Party of America, citing Debs: “We have nothing special to offer the negro, and we cannot make separate appeals to all the races.” Could you situate this within the broader context of the terms of the debate within the Party? What was it about the arguments of the Left of the Party that, for you, made them Left?

TJ: In terms of Debs, you have a small element of — not solely but predominantly African American members of the Socialist Party — who were fighting for a more muscular position on the fight against racism. On the other hand, you had people who were essentially racists within the Socialist Party and thought it was a hindrance, that even raising the question of racism would divide the working class, so it was better off untouched. Debs was in the middle: recognizing discrimination, recognizing that it was wrong, but then saying tactically, “we have nothing special to offer the negro.” He meant, “we don't have a unique program for them.” His thinking was that creating a special program would alienate many white workers. Essentially, African Americans would just have to wait until the working class had overthrown the bourgeoisie, then they would be able to end political and economic inequality. The Left of the Party was primarily African American socialists, and when you read the minutes of the socialist conventions, when dealing with this issue it is overwhelmingly African American members of the Socialist Party who are raising it. A few whites are allied with them — a minimal number. The other side was made up of anything from people who were racists, to those who saw no significance to this question at all. I think that Debs tries to fall in the middle of that, and he made significant anti-racist statements. He would speak about it but did not think it should be stressed because of racism; he found it a divisive question that would be better solved when socialists were in control. By “the Left," I'm assuming that anything that is genuinely Left is anti-racist. There may be another context where the Left and Right change.

DD: What was the relationship between the Communist Party, USA’s (CPUSA) line during this time and its political activity, both among black Americans and elsewhere?

TJ: One of the reasons the Party sent organizers into the South and one of the things they did, particularly in cities like Birmingham, was to organize unions and fight for unions to take anti-racist positions, which was not easy in Alabama or in the other more industrial areas of the South in the 1930s. What I found most interesting, where I've done some research and writing, is what they did in rural areas, primarily centered in Alabama, where the Party initiated an organization called the Sharecroppers’ Union. They sent organizers down from the North. One of the first organizers was Mack Coad, who eventually fought in Spain, but he was the first to organize the Party down there. The idea was to organize sharecroppers and get them to bargain with the landowners for a more significant share of the crop. The next step was to take the landowners’ land from them and divide it equally among the sharecroppers. That was kind of the longer-range vision, and after that the goal was to create a referendum on what status this area of the South should have: should it be a separate state in the United States, seceded from Alabama and Mississippi in those other areas, or should it be an independent nation? Again, that is the Black Belt thesis. There are all kinds of documentation of sharecroppers, many of whom were illiterate, learning to read by reading The Daily Worker, and, in that context, having discussions on self-determination in the Black Belt, on worldwide issues, African colonialism, etc.

Party leaders, particularly white Party leaders, struggled with this issue because they organized black and white sharecroppers. You will see Party organizers writing back to New York saying, “if we could just get rid of this social equality issue, we could have thousands of white sharecroppers in our organization, but if we are lifting the rights of African Americans, white sharecroppers are not going to come near us.” The people in New York held the firm line that this is a principled question. The question of African American equality could not be bargained over or lessened to grow the ranks. Throughout the 1930s, the Party held that principled position, and as a result, except for a few Party organizers sent down there [from the North], the entire Party was African American in the rural deep South in that period, including Alabama. Alabama was the center of it because that is where most of the organizing went on, but also Mississippi and into parts of South Carolina and North Carolina. They organized the Sharecroppers’ Union; not everybody in the Sharecroppers’ Union was in the Party. Of course, the leadership was, and then also within the Sharecroppers’ Union they organized a women's organization and a youth organization. These were times when people had to meet in secret, because the Klan and police were essentially the same thing and would break up the meetings. Ultimately, that kind of organizing was not tenable, because frankly, too many people were being murdered. The South was more like a fascist country than the rest of the United States. The large landowners who were the supporters of the Klan, hired the police, who were largely members of the Klan. Once they found or identified somebody as an organizer of the Sharecroppers’ Union or an organizer for the communists, they murdered them.

With the passage of the civil-rights laws in the 60s, if a murder like that happened in the South, and the local authority did not prosecute it, the federal government could come in and prosecute the case. You see an example even much later with Emmett Till and that trial, where it was evident that they had killed this kid. Due to the national and international pressure around the case, they were forced to bring it to trial, but an all-white jury said, “not guilty.” That’s in the 50s; it was even worse in the 30s where nobody would even be brought to trial. It is a reminder of the Los Angeles Police activities; whenever there was a shooting incident, the police write up their report of what happened. They always had this thing where they would say, “this person was shot, and that person was shot,” and then they would add “NHI,” at the bottom of it, which stood for “no humans involved.” Meaning, these are all black people who were getting killed. This is in Los Angeles in the 60s and 70s. In the South, it was similar. They didn't consider black people as humans. If a landowner murdered one of his sharecroppers because he found out they were in the Sharecroppers’ Union, the police would not arrest or investigate because they would consider it the murder of someone who had no rights anyway. Hence, there were countless cases of murders that went on. Although the internal Party documents do not report this. I think part of the reason is they realized the organizing was unsustainable. Not only were they losing some of their most talented organizers, but they were also just being murdered, and nothing could be done about it, and the sharecroppers were taking the brunt of this. They could not protect them. This coincided with the development of the Popular Front, and so the Sharecroppers’ Union merged into a broader union that was more widespread but was much less Left. A lot of the Party activities were minimized after that point just because of the suppression of the movement. However, it showed that the Party was willing to commit personnel, including giving people’s lives, to go and organize under the basis of perceiving the African American question as a national question and putting the interests of the African American community at the center of the class struggle at that time.

DD: The policy of self-determination for the Black Belt was first adopted in the late 1920s, around the time of the so-called “Third Period” in Comintern policy. Did the subsequent development of Popular Front policy in the mid-1930s influence the Party's attitude towards the issue of racial oppression?

TJ: It was ironic because in the Popular Front, the Party took a less abrasive position among people in the broad democratic movement and took a less sectarian position. In the South, it was hard to do because, in the North, you had a sizable liberal segment of the Left and a large non-communist progressive segment of the Left, you did not have that in the South. That is one of the reasons why a lot of the work diminished in the South. Still, in the North, it put the Party in a much-strengthened position to work, particularly within the African American community, because no longer were you out calling the NAACP a sellout or something like that. Now you were working with the NAACP and influencing them. It also was a period where the Communist Party had a significant influence among the African American creative figures. When I was the director of the Tamiment Library at New York University, which holds the papers of the Communist Party, Abraham Lincoln Brigade, and a lot of left-wing organizations and movements, I saw this poster for Ben Davis, who was an African American communist, but who was elected to City Council in New York, representing Harlem. There was a poster of a fundraiser for him that had Charlie Parker and several great jazz musicians playing, which reflects how the Party influenced the culture of that time. Writers like Langston Hughes were very close to the Party, and, at some point, it is difficult even to determine who was literally in the Party and who was in the orbit of the Party. It is more significant to look at the Party's influence over that broader movement. The Harlem Party was active in tenant organizations and the struggle against fascism when it first began, the Ethiopian support movement in the 1930s, and organizing trade unions. You saw that kind of opening in the Popular Front, not this idea that revolution is right around the corner. Still, the emphasis on winning the democratic struggle, I think, opened the black community to the Party's influence in a much greater way. I lived in Chicago, and you could see the same thing historically happened there in the late 1930s into the early 1940s. The Communist Party on the South Side played a significant role. Leaders like Claude Lightfoot lived in Chicago and was also a national leader in the Party.

DD: What was the significance of the distinction between race and nation? Specifically, it seems to pose the question of racial integration vs. national self-determination.

TJ: In terms of race and nation, first, the problem with race is there is no scientific definition of race. It has no meaning that you can pin down. Looking at it as a national question gives you a framework that can be based on science and practice in terms of how the international movement has taken positions on the issues of colonialism. The Communist International's position in support of the colonial revolts was not based on race but colonization and the oppression of nations. This framework allowed you to deal with the question in more scientific terms. Suppose you have a person who is a product of one parent being white and the other parent being black. What, other than the social circumstances they live in that define that person as black, except something that has long been a product of U.S. law, which says that one drop of black blood makes you black? That existed because the percentage of African-descended people was always relatively small, meaning 10%. If you look at Brazil, it is an entirely different definition of what [being black] means because the percentages of people of color are so large. The idea of bearing away from race is hard, even colloquially using that term as we talk about racism all the time. It is hard to get away from that term because that is the way that most people talk about it, but there is a difference between writing a leaflet or theorizing about a subject. When you are trying to create theoretical categories to use the science of Marxism-Leninism to interrogate that situation, you want to use scientific categories, not popular categories.

DD: How did the political stance of the CPUSA in the 1930s affect the subsequent history of the Left? Is there a relationship between the Black Belt thesis and subsequent attempts to theorize and organize around the question of racism later, particularly in the 1960s?

TJ: One of the essential things is the Communist Party taking up the question of African American equality and making that a principle question, something that there's no compromise around. I think it has had a significant influence on the broader Left. One might argue that some elements of the IWW (Industrial Workers of the World) had anti-racist positions. Generally, no other left-wing movements held that position. To a degree, that is what the Party became identified with at that time. Whenever you saw a white person speaking against racism, they were automatically tagged as a communist. In the 30s and 40s they probably were, because there were very few other multi-racial or multinational groups. The CPUSA position significantly influenced all the New Left groups in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. Oddly enough, many of those, particularly Maoists, resurrected the Black Belt thesis. The Communist Party (Marxist Leninist), Communist Labor Party, and smaller collectives in various cities all adopted that, because, following Maoism, they said, “the Soviet Union is revisionist.” We must look at when the Communist Party was not revisionist. When you look at that period, that is when they had the Black Belt, so they saw a connection between “revisionism” and getting rid of the self-determination for the Black Belt. They thought that to go back to communism, the revolutionary period, let's resurrect the Black Belt thesis.

Groups like the Communist Workers Party had a shoot-out with the Klan in Greensboro. They also followed the Black Belt thesis. But more important than those who followed, as a number did not adopt the Black Belt self-determination thesis, was that one of the things that the Communist Party succeeded in was wedding this notion that to be a communist, to be a Marxist, to be a Marxist-Leninist is to have an uncompromising position on racism and on the oppression of African Americans and for the equality of African Americans, Latino Americans, and Asian Americans, etc. Remember, the Communist Party was the one organization on the Left having that position at one point. Now, every organization on the Left has that position; even organizations that aren't necessarily on the Left but are progressive are more likely to raise the questions of racism and inequality than before. If you look at the early struggles in the Civil Rights Movement, particularly those in the South, but even in the North, you see very few whites involved. Even in the North, the involved whites were communists or related or influenced by the communists. Still, suppose you see the recent demonstrations taking place against police brutality. Whether in New York City or Kenosha or any of these other cities where there are these big “defund the police” marches, you see large numbers of whites, young whites, who are not necessarily Left, not in any organizational sense. A result of the work of the communists and many other people was to bring the issue of racism, the issue of African American inequality, to the center of social struggles. So that now, even when you see organizations, some of whose primary concern is the environment, you'll see they have some anti-racist statement involved. The Party has been doing that since the 30s — that has been an influence. The strong anti-racist positions have been infused into almost every movement, like the broader progressive movement that exists in the Women's Movement, the Gay Movement, all those kinds of things. You see most of them have, at the center, some strong statements against racism, which communists might call national oppression, but colloquially is called racism. |P