The usable Gramsci?

Martin Thomas

Platypus Review 144 | March 2022

THE SIX RECENT CONTRIBUTIONS I will survey here mostly seek to identify an Antonio Gramsci usable for active socialist politics amidst the welter of Gramscis around us. They construct their usable Gramscis mostly from the terms which have figured largest in the “orthodox” Gramscis since the 1950s (the Italian Communist Party’s (PCI), the Eurocommunist, and then the academic): hegemony and war of position. My case will be that active socialists can gain more from seeing Gramsci’s arguments around those terms as weak areas, and starting with stronger seams of Gramsci’s writing.

Jan Norden finds nothing usable.[1] He interprets Gramsci’s argument about hegemony as that “before considering the seizure of political power, one would first have to struggle to conquer cultural leadership.” The decisive word in this presentation is “cultural”: that socialists have to struggle to win political leadership in the working class before seizure of political power is only a commonplace rejection of putschism. With the tweak to “cultural,” however, Norden identifies the “Gramscian” argument as one suited to “former leftist students turned academics.”

Gramsci himself did not drift from activism to academia, but Norden indicts him in 1919–20 as complicit in the Italian Socialist Party (SP) leaders’ “eternal waiting.” (Gramsci was at the time a young activist with a small group of co-thinkers in Turin. He was unable to solidify an Italy-wide faction to challenge the SP leaders effectively, as also was Amadeo Bordiga, the more established leader of the revolutionary wing of the SP.) Norden also indicts the Trotskyist Faction and Left Voice as being ready to “raise a transitional program which includes the defense of bourgeois democracy,” and sees Gramscianism there. Trotsky, claims Norden, “never presented a ‘program of radical democracy.’”[2] Yet Section 16 of the “Program of Action for France” written by Trotsky in June 1934 was exactly that.

Massimo Amadori equally identifies his Gramsci as one of “war of position” and “cultural hegemony,” but approvingly.[3] “War of position” is just a “perspective [which] did not exclude united fronts with other left forces and struggles for democratic goals;” the “concept of ‘cultural hegemony’” was “an attempt by Gramsci to adapt a Leninist strategy to a Western context” and was “also present in the work of Lenin.”[4] This account, in its own way, yields as little “usable Gramsci” as Norden’s: the usable ideas are already available, and less cryptically-worded, in Lenin.

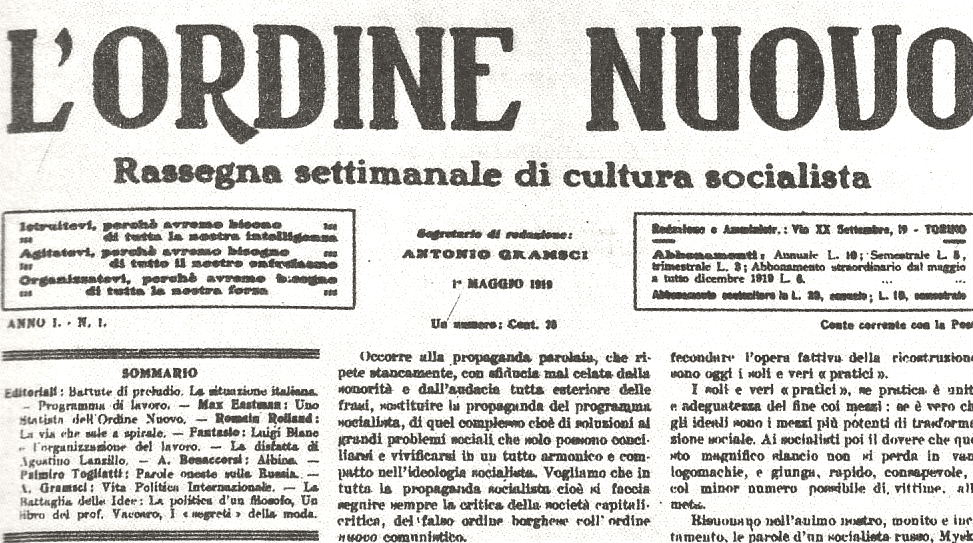

Lenin advocated “hegemony” of the working class in the fight against autocracy in Russia. In a 1911 polemic against liquidationists, he wrote, “The hegemony of the working class is the political influence which that class (and its representatives) exercises upon other sections of the population by helping them to purge their democracy (where there is democracy) of undemocratic admixtures, by criticising the narrowness and short-sightedness of all bourgeois democracy, by carrying on the struggle against ‘Cadetism’ [...], etc.”[5] The Russian Marxists did not write about “cultural hegemony.” Neither, mostly, did Gramsci. Before prison Gramsci had criticized the early issues of L’Ordine Nuovo[6] as an “anthology” of “abstract culture,” before it was reoriented to the Turin factory councils.[7] In Russia in 1922–23 he had contributed a chapter to Trotsky’s Literature and Revolution (1924). He must have been aware of the polemics by Trotsky against the idea that a “proletarian culture” could become hegemonic even after a socialist revolution. The working class would have much to do to educate itself even in bourgeois culture. By the time that was complete and class divisions had withered, the new culture would be “socialist” rather than “proletarian.” Gramsci never disputed that view, which won out among the Bolsheviks.

The word “hegemony” appears often in the Prison Notebooks, and the words “culture” and “cultural” too. The term “cultural hegemony” appears rarely, and, as far as I can make out, as part of formulations like “political and cultural hegemony,” or “cultural and moral hegemony.” The Notebooks equate “cultural” with “ethico-political,” or with the combination-merger of politics and philosophy, or just with “ethical,” rather than with “the arts” and such. Gramsci argues not for replacing political activity by diffuse cultural promotion, but for a “broad” conception of politics, embracing reflection on different ethics and ways of life, rather than a narrow one. Even before prison, Gramsci had described L’Ordine Nuovo (after its reorientation) as a “communist cultural review,” though in fact it was a political newspaper, with a broad range of coverage. “The nature of the philosophy of praxis is [...] that of being a mass conception, a mass culture [...] The activity of the ‘individual’ philosopher cannot therefore be conceived except in terms of this social unity, i.e. also as political activity, in terms of political leadership.”[8]

Michael Denning also equates Gramsci with “war of position” and a cultural focus, only he argues that the usable version of these ideas today is to inform the activity of “organizers” in the Saul Alinsky tradition.[9] Previously, he writes, there have been “two major forms of Gramscian politics.”[10] One was through political party activity, and he identifies the Italian Communist Party of the 1950s–80s as an authentic exemplar. The second form was a “war of position across the cultural organizations [...] in education, journalism, popular culture, and philosophy.”[11] Both forms, he says, "seem exhausted.”

Today, Denning claims, “young activists think of themselves as organizers (of a variety of stripes) not as partisans (party members).”[12] They can work at “the reformation of the national-popular collective will—in the workplace, the neighbourhood, the household, the police precinct, even the legislature.”[13] Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, he reminds us, has said, “‘The way that I think of myself is an organizer [...] building a coalition, deepening that coalition with other organizers.’”[14] The usable Gramsci can take us beyond “the received US ideology of organizing, which tends to bracket ‘ideological’ issues from ‘pragmatic’ concerns.”[15]

Denning takes his cue from Gramsci’s comment that “everyone is a legislator in the broadest sense of the word.”[16] That comment parallels Gramsci’s more famous remark that “everyone is a philosopher;”[17] everyone has a “conception of the world” (philosophy) embedded in our communications, even if lacking in self-awareness, critical working-through, and coherence. Everyone is a “legislator” in the sense of promoting “‘norms’, rules of living and of behaviour” in our own circle.[18] But the ruling class are, by definition, the decisive “legislators;” the working class can become “legislators” in more than a minimal or notional sense only by taking power, and that can be done only after we (or enough of us) have become “philosophers” in a more critically-worked-through way.

The shift from “everyone a philosopher” to “everyone a legislator” signals a shift from developing a unified and coherent political force to establishing oppositional “‘norms’, rules of living” in a scattershot variety of areas. That is to be done by the “organisers,” which in the U.S. means the vast numbers of Left-minded young people employed by “nonprofits,” community organizations, labor unions, NGOs, etc. Even if the “organizers” question Saul Alinsky’s original emphasis on pragmatism against ideology, as Jane McAlevey for example does, and emphasize in-person conversation on the ground above electronic messaging from an office, as McAlevey also does, this gives us a tame and diffuse “usable Gramsci.”

Nicholas Stender offers a “usable Gramsci” which contrasts with both the image of socialist “hegemony” welling up from below through miscellaneous organizing efforts, and that of it seeping down from incremental efforts in cultural institutions.[19] He cites as Gramsci’s image of bourgeois hegemony an outburst of October 1919: “The revolution finds the broad masses of the Italian people still shapeless, still atomised into an animal-like swarm of individuals lacking all discipline and culture, obedient only to the stimuli of their bellies and their barbarian passions.”[20] Winning socialist hegemony is about the socialists educating that “swarm.” Stender does not mention “war of position;” his “usable Gramsci” focuses on another well-known term, the “organic intellectual.” “Organic intellectuals,” he explains, are class-conscious workers who educate their workmates: they are enabled to do so by the discipline of a revolutionary party.[21]

In his writings before jail, Gramsci occasionally vented exasperation against people around him, most of all urban petty officials and professionals drawn from the rural population, but also sometimes workers or even the dilatory members of his own party, as “lacking discipline and culture.” A major element, however, and a valuable one, of the discussion of “hegemony” he later developed in the Prison Notebooks, was the thought that what socialists characteristically have to deal with in the working class and the middle classes is different forms of “discipline and culture,” not a shapeless absolute lack of it: namely, a “discipline and culture” shaped both by the many ideological workings of the bourgeois state and other bourgeois institutions and by class activities. To replace those contradictory forms of “discipline and culture” by a coherent socialist form requires both discerning and building on the solidaristic and emancipatory elements in people’s previous multifaceted thinking, and educating ourselves sufficiently to tackle the bourgeois ideologies even in their best forms.

I find Gramsci’s dichotomy between “traditional” and “organic” intellectuals one of his most confused conceptualisations. He writes that “Every social group, coming into existence on the original terrain of an essential function in the world of economic production, creates together with itself, organically, one or more strata of intellectuals” (technicians, economists, lawyers, entrepreneurs, etc. for the capitalist class); it also finds “categories of intellectuals already in existence and which seemed indeed to represent an historical continuity uninterrupted even by the most complicated and radical changes in political and social forms.”[22] The archetype for Gramsci of the second-type “traditional” intellectuals is “ecclesiastics.” In the Italy of Gramsci’s day the Catholic Church was a great ideological power but maintained distance from bourgeois governments: from 1868 to 1918 it enjoined the faithful neither to vote nor to stand in elections. No wonder Gramsci wanted to explore the role of the priests as a special body of intellectuals. Dissolving that specific problem into a universal dichotomy between “organic” and “traditional” intellectuals does not help. Other sorts of intellectuals whom he described as “traditional” were “the man of letters, the philosopher, the poet.”[23] But, in fact, to be a qualified technician or lawyer requires training in a “tradition” of knowledge going back over centuries and relatively independent of the ruling class of the day, whereas you can be a poet without rooting your work in knowledge of previous poetry. Gramsci elsewhere emphasizes the need for the working-class socialist movement to win over technicians, supposedly the archetypal “organic intellectuals” of the capitalist class. Trade-union officials, in a stable liberal bourgeois democracy, are simultaneously “organic intellectuals” both of the working class (by day-to-day efforts to represent worker interests) and of the capitalist class (by disseminating ideas of class conciliation). In latter-day efforts to construct a “usable Gramsci,” the term “organic intellectual” tends to become a term for someone deemed “in touch.” (For example, an obituary of the prominent “post-Gramscian,” Ernesto Laclau, refers to him, son of a diplomat and a lawyer, and an academic all his adult life, as an “organic intellectual.”[24]) Stender’s use of the term can serve no more than to give members of his group the glow of feeling that, if they are disciplined and promote the group’s politics assiduously, then they become “organic intellectuals,” who as such, even if they know little, become superior to “traditional intellectuals.”

Chris Maisano explicitly rejects a “culturalist” reading of hegemony.[25] He argues that hegemony in Gramsci is centrally about politics: “Is hegemony, a fundamentally cultural concept for Gramsci, as it is for many of his supposed followers? [...] It is not.”[26] “What Gramsci called the ethico-political dimension of political struggle has little to do with the emphasis on storytelling and communication strategy that’s so common in the NGO sector today. It refers instead to the creation of an integral worldview grounded in the workers’ experiences of daily life through a protracted process of collective political education and organization-building.”[27]

Maisano’s “usable Gramsci,” however, promotes “war of position” as describing a strategy required in more advanced capitalist states, in contrast to “war of maneuver” supposedly exemplified by the October 1917 Revolution in Russia. He indicates that he finds the approach of the Italian Communist Party from the 1950s to the 1980s a genuine, though not flawless, exemplar:

There’s a lot that you can still get out of Gramsci and his writings and, I think, also the historical practice [...] of the Italian Communist Party. [...] Gramsci and [...] many of [...] his milieu [...] were concerned above all else with remaining in contact with the masses of working people in their society. The tension here is that, and I think the Italian Communists faced this [is that] if you do succeed, I think in building up a large organization or set of organizations within the shell of the broader capitalist society, that is going to make people [...] interested in [...] maintaining them, keeping them going [...] on their own terms and not doing anything that might threaten or disrupt their ongoing existence, that would threaten their institutional or political survival [...] It’s a real dilemma [...] The Left nowhere has really figured out how to do that. The Italian Communists did not [...] Here in the United States, we’ve never had the opportunity, unfortunately, to actually grapple with that dilemma.[28]

But, he indicates, for now let’s get to the point where the dilemma arises.

There is “Gramscian” sense, in my view, against political approaches on the revolutionary Left, which focus almost entirely on boosting immediate economic and similar militancy, with the implied perspective that enough of that plus economic crisis will eventually explode into revolution as long as a big enough revolutionary organization has been built — “almost entirely” to the extent that battles for democracy, patient education, sober appraisal and so on are downplayed. A passage from the Prison Notebooks which reads like a critique of strands of Bordiga’s thought is relevant. Gramsci criticizes:

The iron conviction that there exist objective laws of historical development similar in kind to natural laws [...] favourable conditions are inevitably going to appear, and [...] these, in a rather mysterious way, will bring about palingenetic events [...] Side by side with these fatalistic beliefs, however, there exists the tendency “thereafter” to rely blindly and indiscriminately on the regulatory properties of armed conflict. [...] Destruction is conceived of mechanically, not as destruction/reconstruction. In such modes of thinking, no account is taken of the “time” factor, nor in the last analysis even of “economics.” For there is no understanding of the fact that mass ideological factors always lag behind mass economic phenomena, and that therefore, at certain moments, the automatic thrust due to the economic factor is slowed down, obstructed or even momentarily broken by traditional ideological elements — hence that there must be a conscious, planned struggle to ensure that the exigencies of the economic position of the masses, which may conflict with the traditional leadership’s policies, are understood. An appropriate political initiative is always necessary to liberate the economic thrust from the dead weight of traditional policies [...].[29]

However, Maisano’s “usable Gramsci” goes beyond that to become an authority for the “anti-insurrectionary,” “transformative reforms,” “revolutionary social democracy” wing of the Democratic Socialists of America and, more, for assimilating that wing to the approach of the Italian Communist Party between the 1950s and the 1980s and taking it as an exemplar of “usable Gramsci.”

Francesco Giliani offers a crisp demolition of the example.[30] The PCI’s approach was already flatly reformist and class-collaborationist when it emerged from clandestinity with the fall of Mussolini in 1943–45. It did not just fail at the final hurdle on counteracting the inevitable conservatism which arises after relative positions of strength are won. From the 1940s onwards the PCI constructed “a Gramsci who rigidly opposed the war of position (i.e. the slow construction of an anti-capitalist bloc) to the war of manoeuvre (i.e. an open offensive against the bourgeoisie).”[31] (In fact, the “bloc” constructed was not really even anti-capitalist: its aim was the PCI’s inclusion in a governing coalition, or a more “advanced democracy.” with actual anti-capitalism relegated to a distant next stage.)

Maisano seeks to dissociate his “usable Gramsci” from the Gramsci misused by advocates of the pursuit of loose cultural influence as a substitute for political activity. Why, he asks, was Gramsci vulnerable to such misuse? “Gramsci’s work doesn’t really get translated into English until the 70s [...] And this is precisely the period in which the Left, the working-class movement, labor movements are starting to come under very serious attack in many capitalist countries [and] largely defeated [...] The most iconic example of that being Margaret Thatcher’s defeat of the coal miners’ strike in Britain in 1984 and 1985 [...] [Gramsci’s] discussions of popular culture or ideology [...] created, I think, an opening for people who may have been, say, dispirited or disappointed by the various defeats [...] [and for] quite one-sided readings of a lot of his work.”[32]

Maisano’s chronology is wrong. As Giliani shows, a Gramsci “usable” for reformism had been formulated by the PCI leaders decades before. It was disseminated internationally long before the defeats of the 1980s; and contested by revolutionaries, too.[33] Sizeable one-volume selections from Gramsci were published in French in 1959, in German in 1957, and in Spanish in 1970. The ferment in the French Communist Party student organization in the early 1960s which would in 1966 produce sizable Trotskyist and Maoist spin-offs, also featured a “pro-Italian” faction, though that subsided. A short Gramsci selection was published in English in 1957. New Left Review published a PCI-like “Gramscian” account of “Problems of Socialist Strategy” in 1965. The large Selections from the Prison Notebooks were published in 1971, and debated over a full decade of Left-wing buoyancy before Thatcher started dispersing and dismaying it.

In the 1970s, the PCI’s approach gained ground with other Communist Party leaderships and educated thousands of activists in so-called “Eurocommunism.” The further step from “Eurocommunism” to a “Gramsci” one-sidedly “culturalist” and with scant or no relation to the working class or socialism came with the decline, dissipation, and sometimes winding-up of the Communist Parties in the 1980s and early 1990s, a process driven by the decay and then sudden collapse of the command economies in Eastern Europe and the USSR. Thousands of people concluded that what they had thought to be socialism was unviable and maybe not even desirable. Those who wished to continue to be active in a Leftish way could adapt the “usable Gramsci” of the 1950s–60s PCI and later Eurocommunism just by deleting some tenuous “in the last analysis” connections.

Giliani’s article, a solid and useful piece of work, also gives a reasoned dissection of the fumblings of Gramsci’s policy when he was leader of the PCI between 1923 and 1926. Giliani does not dismiss Gramsci in the way that Norden does, but the focus of his article is not on a “usable Gramsci” for revolutionary socialists, rather on dissecting the PCI’s and Eurocommunists’ “usable Gramsci.” Giliani refers to Perry Anderson’s book (originally published in 1976 as a special issue of New Left Review) on The Antinomies of Antonio Gramsci. That Gramsci should be “usable” by the PCI and such requires no special explanation. Marx, Lenin, and others have in their time been made “usable” by people using shreds of quotation to aliment politics quite different from the authors’. Since Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks are a miscellany of short notes, written in difficult conditions, often cryptic, the adaptation to varied purposes is even easier. Anderson argues that there are internal “antinomies” in Gramsci’s writings which facilitate it. Gramsci usually locates hegemony as operating in “civil society” and by means of developing “consent.” But many constructions of bourgeois consent operate through the state (for example, the very structures of bourgeois democracy, as distinct from the parties which can be located in “civil society”) or by “dull economic compulsion” (commodity fetishism); and there is “coercion” in civil society. Gramsci often omits economic structures from civil society. The theoretical construction makes almost invisible the difference between bourgeois democracy and fascism. The “war of position” argument sometimes approximates Karl Kautsky’s “attrition strategy” developed in polemic against Rosa Luxemburg in 1910–11.

Indeed, more can be said along Anderson’s lines.[34] We should take Gramsci’s own warning: “Comparisons between military art and politics, if made, should always be taken [...] with a pinch of salt [...] In political struggle, there also exist other forms of warfare—apart from the war of movement [...] or the war of position.”[35] Even within those limits, suggestions that we must have “war of position” today in contrast to Bolshevik “war of maneuver” rest on a misperception of the October 1917 Revolution as having been made by a sudden “frontal offensive” once a quasi-military party organization had gained strength. In fact, the final uprising was much less spectacular than the February Revolution, and was prepared through a sinuous and careful selection of tactics and initiatives, mostly about winning “consent” (a majority in the soviets, and soviet authority in the population). The counterposition of East and West is schematic: Tsarist Russia had a ramshackle state machine, which moreover largely disintegrated after the February 1917 Revolution, while countries like Germany, Italy, or France had much more resilient state machines. Tsarist Russia had a complex civil society.

The Prison Notebooks were not written to investigate revolutionary socialist strategy in stable, or relatively stable, bourgeois democracies. Gramsci saw fascism as more typical for Europe in his day: “in the present epoch, the war of movement took place politically from March 1917 to March 1921: this was followed by a war of position whose representative — both practical (for Italy) and ideological (for Europe) is fascism.”[36] In what Gramsci saw as a more stable bourgeois democracy, the U.S., he misperceived, writing that there “hegemony is born in the factory and requires for its exercise only a minute quantity of professional and ideological intermediaries” and that in the U.S. “there [had] not been [...] any flowering of the ‘superstructure.’”[37] Gramsci read Henry Ford’s tactics in his factories one-sidedly and over-generalized. In fact the U.S. has long had exceptionally many “professional and ideological intermediaries” of bourgeois hegemony: lawyers, real-estate agents, professors, priests and pastors, university professors, politicians, etc.

When Gramsci discusses hegemony in the Prison Notebooks, he may have in mind fascist Italy, the Bolsheviks’ efforts to reassemble popular support in the New Economic Policy period, or liberal Italy from the Risorgimento to the World War — and sometimes it is difficult to know which — but never a latter-day relatively stable, urbanized, secular bourgeois democracy. Ideas from the Notebooks’ discussions of hegemony can be made “usable” today, but only with selection and care. Gramsci was aware of the asymmetry between bourgeois ways of constructing hegemony (i.e. winning political leadership) and working-class socialist ways of doing that. “In political struggle one should not ape the methods of the ruling classes.”[38] “The philosophy of praxis [...] does not aim at the peaceful resolution of existing contradictions in history and society but is rather the very theory of these contradictions. It is not the instrument of government of the dominant groups in order to gain the consent of and exercise hegemony over the subaltern classes; it is the expression of these subaltern classes who want to educate themselves in the art of government and who have an interest in knowing all truths, even the unpleasant ones, and in avoiding the [...] deceptions of the upper class and — even more — their own.”[39] But on a first reading the Prison Notebooks often look like they are discussing techniques of hegemony equally usable by either class.

Gramsci did not write the Prison Notebooks as a guide to current politics. He was likely to be in jail for a long time; he was too ill to do much in current politics even if released from jail; he had little way of offering political direction to people outside; by the time the prison authorities permitted him to use pen and notebooks in 1929 he was out of tune with the now-Third-Period Communist Party yet felt unable to link with oppositional communists. So he chose to write on longer-range historical, philosophical, and scientific issues.

His writings diverged from his planning lists, but in those lists “the development of Italian intellectuals” was top in 1927, “formation of Italian intellectual groups” third in February 1929, “Italian history [...] with special attention to [...] intellectual groups” first in March 1929, “intellectuals” first in March–April 1932.[40] Some of the writing on “intellectuals” was of a more distanced historical character. In some, though, he is discussing why the intellectual leaders of the Socialist Party were ineffectual in 1919–20; why the early Communist Party under Bordiga’s leadership was also ineffectual in a different way (membership went down from 40,000 in early 1921 to 5,000 in late 1923, and was rebuilt under Gramsci’s leadership, despite fascist rule, to over 25,000 before the full fascist clampdown in 1926); why Third-Period policies were folly; why the liberal intellectuals who had ruled Italy for decades collapsed so ignominiously before fascism; and why so many syndicalist intellectuals went over to fascism.

Those writings give us much “usable Gramsci.” For our time it helps that he was discussing political issues of long hauls, not responses to immediate crises, which dominated the writings of, for example, Trotsky in the 1930s. Gramsci went beyond generalities about hegemony or lack of it. The liberals had hegemony over the people of Italy for decades; the Socialist Party had hegemony in the Italian working class around the end of World War I. The question was why those “hegemonies” proved so ineffectual, which required an examination of what Gramsci called the “hegemonic apparatus.”

Gramsci moved away from the scheme, which spills into his pre-prison writings from time to time, of an enlightened few instructing an ignorant and thoughtless mass, and, in many “usable” sections of his investigations, towards specifics of how and what sort of hegemony. He continued to insist that “instruction” is a vital element in education. It is not all “learning by doing.” But he insisted on a positive engagement with “spontaneous” class battles. “‘Pure’ spontaneity does not exist in history [...] In the ‘most spontaneous’ movement it is simply the case that the elements of ‘conscious leadership’ cannot be checked, have left no reliable document. It may be said that spontaneity is therefore characteristic of the ‘history of the subaltern classes.’”[41] In the Turin movement of 1919–20, he wrote proudly:

This element of “spontaneity” was not neglected and even less despised. It was educated, directed, purged of extraneous contaminations; the aim was to bring it into line with modern theory — but in a living and historically effective manner [...] Neglecting, or worse still despising, so-called “spontaneous” movements, i.e. failing to give them a conscious leadership or to raise them to a higher plane by inserting them into politics, may often have extremely serious consequences. It is almost always the case that a “spontaneous” movement of the subaltern classes is accompanied by a reactionary movement of the right-wing of the dominant class [...].[42]

Gramsci’s image for the socialist party “intellectual” was the “permanently active persuader,” or under conditions of bourgeois-democratic freedom, “the democratic philosopher”:

The environment reacts back on the philosopher and imposes on him a continual process of self-criticism [...] his personality [...] is an active social relationship of modification of the cultural environment.”[43] Socialist development of intellectuals and hegemony contrasts sharply with that of the Catholic Church. In the Catholic Church, the “split [between little-educated believers and the intellectuals] cannot be healed by raising the simple to the level of the intellectuals (the Church does not even envisage such a task, which is both ideologically and economically beyond its present capacities), but only by imposing an iron discipline on the intellectuals so that they do not exceed certain limits of differentiation and so render the split catastrophic and irreparable [...] The position of the philosophy of praxis is the antithesis of the Catholic. The philosophy of praxis does not tend to leave the ‘simple’ in their primitive philosophy of common sense, but rather to lead them to a higher conception of life. If it affirms the need for contact between intellectuals and simple it is not in order to restrict scientific activity and preserve unity at the low level of the masses, but precisely in order to construct an intellectual-moral bloc which can make politically possible the intellectual progress of the mass and not only of small intellectual groups.[44]

As with the Bolsheviks, the Socialist Party works to weld “intellectuals” (writers, organizers, etc.) with scant “traditional” education together with those of high “traditional” education in a single comradeship without tiers.

Gramsci also draws a contrast with the old Socialist Party: “a paternalistic party of petty bourgeois with a ridiculous sense of self-importance,” which had “a fatalistic and mechanistic conception of history” and yet “a total lack of understanding of [the working class’s] latent energies.”[45] The old Socialist Party membership had been 90+% worker and peasant; but its leaders were mostly people of “traditional” high education, and there was little effort to develop “intellectuals” from the rank and file. The party’s culture was oratorical and agitational, rather than written and precise. “The political parties: they were hardly solid, and they lacked consistent vitality; they only sprung into action during electoral campaigns. The newspapers: their connections with the political parties were weak, and few people read them.”[46]

In contrast, Gramsci outlined the requirements for solid socialist organizing:

This organic continuity requires a good archive, well stocked and easy to use, in which all past activity can be reviewed and “criticised”. The most important manifestations of this activity are not so much “organic decisions” as explicative and reasoned (educative) circulars. There is a danger of becoming “bureaucratised”, it is true; but every organic continuity presents this danger, which must be watched. The danger of discontinuity, of improvisation, is still greater. Organ: the “Bulletin”, which has three principal sections: 1. directive articles; 2. decisions and circulars; 3. criticism of the past, i.e. continual reference back from the present to the past, to show the differentiations and the specifications, and to justify them critically.[47]

To start searching for the “usable Gramsci” in the elements of his Notebooks highlighted by the PCI and Eurocommunist traditions (hegemony in general, war of position, East vs. West) is, I think, to choose the wrong entry-point. Better start where Gramsci himself saw his main focus. |P

[1] Jan Norden, “Revolutionary Trotskyism vs. Gramscism: The Programmatic Clash,” The Internationalist (August 2021), available online at <http://www.internationalist.org/trotskyism-vs-gramscism-2108.html>.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Massimo Amadori, “The Revolutionary Legacy of Antonio Gramsci,” Socialist Alternative, February 7, 2021, available online at <https://www.socialistalternative.org/2021/02/07/the-revolutionary-legacy-of-antonio-gramsci/>.

[4] Ibid.

[5] V. I. Lenin, “Those Who Would Liquidate Us,” in Lenin Collected Works, vol. 17 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1963), 60–81, available online at <https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1911/twwliqus>.

[6] L’Ordine Nuovo was a newspaper established in May 1919 by a group within the Italian Socialist Party; not to be confused with the organization Ordine Nuovo, which was founded in 1956 by Pino Rauti.

[7] Antonio Gramsci, “On the L’Ordine Nuovo Programme,” in Selections from Political Writings 1910–20 (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 2003), 293.

[8] Antonio Gramsci, Further Selections from the Prison Notebooks, trans. Derek Boothman (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995), 385.

[9] Michael Denning, “Everyone a Legislator,” New Left Review 129 (May/June 2021).

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Antonio Gramsci, “Who is a Legislator?,” in Selections from the Prison Notebooks (New York: International Publishers, 1971), 265–66.

[17] Ibid., 322.

[18] Denning, “Everyone a Legislator.”

[19] Nicholas Stender, “Antonio Gramsci: A communist revolutionary, organizer, and theorist,” Liberation School (January 1, 2021), available online at <https://liberationschool.org/antonio-gramsci/>.

[20] Antonio Gramsci, “Revolutionaries and the Elections,” in Selections from Political Writings 1910–20, 128.

[21] Stender, “Antonio Gramsci.”

[22] Antonio Gramsci, “The Formation of the Intellectuals,” in Selections from the Prison Notebooks, 5–7.

[23] Antonio Gramsci, Prison Notebooks, vol. 2, ed. Joseph A. Buttigieg (New York: Columbia University Press, 1975), 242.

[24] Adrià Porta Caballé, “Ernesto Laclau (1935–2014),” rs21 (April 16, 2014), available online at <https://www.rs21.org.uk/2014/04/16/ernesto-laclau-1935-2014/>.

[25] Chris Maisano, “The Marxism of Antonio Gramsci and What ‘Hegemony’ Really Means,” Jacobin Stay at Home Podcast (April 16, 2020), available online at <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vBTRI1QDpaY>.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Antonio Gramsci, “Some Theoretical and Practical Aspects of ‘Economism,’” in Selections from the Prison Notebooks, 168.

[30] Francesco Giliani, “Hegemony, war of manoeuvre and position: what remains of Gramsci in Gramscism?,” In Defense of Marxism (January 22, 2021), available online at <https://www.marxist.com/gramsci-hegemony-prison-notebooks-1.htm>.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Maisano, “The Marxism of Antonio Gramsci.”

[33] For efforts at a revolutionary “usable Gramsci” back then, see, for example, Cliff Slaughter, “What is Revolutionary Leadership?,” Labour Review 5, no. 3 (October–November 1960), available online at <https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/slaughter/1960/10/leadership.html>; and the references to Gramsci in Contre Althusser, ed. Jean-Marie Vincent (Paris: Union générale d’éditions, 1974).

[34] Peter D. Thomas, in chapter 2 of his The Gramscian Moment: Philosophy, Hegemony and Marxism (2011), disputes Anderson’s claim of slippages. I think Anderson was right. See Martin Thomas, “Anderson’s antinomies,” in Gramsci in Context: Essays and Interviews, ed. Martin Thomas (London: Workers’ Liberty, 2014).

[35] Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, 120.

[36] Ibid., 231–32.

[37] Ibid., 285–86.

[38] Ibid., 232.

[39] Gramsci, Further Selections from the Prison Notebooks, 395–96.

[40] Antonio Gramsci, Subaltern Social Groups: A Critical Edition of Prison Notebook 25, ed. and trans. Joseph A. Buttigieg and Marcus E. Green (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021), xxxi–xlvii.

[41] Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, 196–97.

[42] Ibid., 196–99.

[43] Ibid., 350.

[44] Ibid., 331–33.

[45] Gramsci, Prison Notebooks, vol. 2, 41.

[46] Antonio Gramsci, Prison Notebooks, vol. 3, ed. and trans. Joseph A. Buttigieg (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 80.

[47] Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, 196.