Vanguard or Avant-Garde? Revisiting questions on leadership: Part 1: The vanguard debate in history

Alexander Riccio

Platypus Review 113 | February 2019

This is the first of a two-part article written by Alexander Riccio. The second part, “Towards a new vanguard theory,” will appear in PR #114 in March, 2019.

Vanguardism is alive and well in the 21st century, yet it rarely gets named as such. One hears often of the need to ‘center’ particular forms of leadership; the leadership of the working-class, or Indigenous people, or Black people for instance. Centering at times refers to placing a particular object of struggle at the forefront of all issues, as in calls to consider climate catastrophe the primary concern for the Left, or the crises of reproduction as the major issue which folds every other into its purview. Ironically, despite such vanguardism, it is also popular on the Left to hear calls for no leaders, for horizontality, for anti-vanguardism.

Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter have brought these paradoxes to the surface, and it appears to me that partly explaining the Left’s inability to firmly dislodge vanguardism is due to a lack of theoretical knowledge and to the fact that historical vanguardist projects possess a number of valuable insights. Yet, it abundantly evident that the majority of leftists today only recall or know of its worst features (namely its elitist and authoritarian track record), and misrecognize them as the sole features of vanguardism.

Occupy Wall Street protests began in September, 2011.

Reducing vanguardist theory squarely as a top-down repressive political form does little to help us make sense of current calls for particular models of leadership. These calls build upon a foundation of political debate rendered incomplete without a full engagement with the theory and history of vanguardist thought. Additionally, ignoring this history allows for some of the least productive aspects of vanguardism to seep into movement spaces without sufficient contestation. For anyone desiring a better world, it is necessary to take seriously the need for political clarity on just what vanguardism has been, how it’s developed, and where we can recognize its dimensions today. Otherwise, the current bewilderment over ‘who will lead’ and ‘who should follow’ will continue to fragment social movement energies and focus.

I will attempt to pull from the best of vanguardist ideas and dispense with their less attractive features, fully recognizing that too often such polemics have produced elitist and authoritarian qualities. Though many on the Left today shun vanguardism as a matter of theoretical principle, vanguardist practices are still all too common, and the common rhetoric of ‘leaderful’ movements effectively veils this reality. My aim is not to suggest the Left adopt one particular organizational form over all others (the party; the autonomous zone; and so on), or to claim the Left needs to embrace vanguardism. On the contrary, the numerous criticisms of vanguardism are valid and should be considered. What I strive to put forward is a more coherent and reformulated conception of the vanguard that is neither authoritarian or elitist, so that if a vanguard takes hold it does not commit the same errors made by historical vanguardist groups (i.e. the Bolsheviks, Black Panther Party, etc.).

Constructing this conception of a vanguard requires an analysis which recognizes the following: 1) leadership and oppression are dialectically shaped; 2) the vanguard should not strictly lead the revolution or act as a lone party force, but work as a frontal assault against capitalist power; 3) capitalism profits through dispossession, making it a force in movement without a permanent spatial or temporal center; and 4) since capitalism has no permanent center there will not be a singular vanguard frontal assault, but a multitude of assaults led by the plural vanguards. I conclude that today’s vanguards act as a force of movement(s) propelled by the sharing of stories which generate empathy and/or solidarity amongst disparate groups, and articulate a collective desire for an open utopia1 where alienation is no longer an oppressive feature of society. Vanguardism, like much revolutionary political theory, is largely an attempt to craft a story about how we can bring about a new world; hence an open utopia. Seeing as the revolution has yet to come, the story needs another chapter.

Quick notes on the current debate

The efficacy of OWS’s and Black Lives Matter’s amorphous ‘leaderless’ structures have been called into question. For OWS, its supposed lack of demands and disavowal of official leaders has been faulted for its decline. Where the former is truly a hollow claim,2 the latter has gained a certain ‘common sense’3 amongst Left intellectuals today. “The ideas of autonomy, horizontality, and leaderlessness that most galvanized people at the movement’s outset,” writes Jodi Dean, “came later to be faulted for conflicts and disillusionment within the movement.” Dean highlights how “assertions of leaderlessness as a principle incited a kind of paranoia around leaders who emerged but who could not be acknowledged or held accountable as leaders.”4 A proposed solution has been found in calls to rebuild a vanguard party, rectifying problems of accountability. Dean argues that OWS was led by an unacknowledged vanguard—a disciplined, invisible cadre of organizers that did the bulk of work and held the early movement intact. Admits OWS organizer Sarah Jaffe, “the ‘leaderless’ structure of Occupy masked the fact that a small core group of people did a large amount of the work.”5 However, as demonstrated below, the real argument is not about having a leaderless/leaderful organization or a party, but about which category of people are expected to be at the forefront of a revolutionary strategy.

Black Lives Matter (BLM) participants frequently cite the need to center the voices of its Black leaders (particularly Black women leaders). According to Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, BLM is “led by women… decentralized and is largely organizing the movement through social media.”6 Yet BLM is still criticized for its lack of identifiable leaders. Yamahtta Taylor explains much of this stems from a “division between the ‘old guard’ and the ‘new generation.’”7 Young or first-time activists within BLM “bring new ideas, new perspectives, and often, new vitality to the patterns and rhythms of activism.”8 The old guard, or ‘the civil rights establishment,’9 is represented by the likes of Reverend Al Sharpton, Jesse Jackson, and leaders of the NAACP. They view the rise in political activity amongst young Blacks as opportunities for increasing Democrat voter turnout, in turn strengthening their own ‘political value.’

Fractures between the ‘old guard’ and ‘new generation’ reveal intra group divisions within Black politics.10 Identifying the interests of an ‘old guard’ requires locating their class positions and political allegiances. Adolph Reed Jr. notes “the record of the black political regime [aka the old guard] consolidated in the late 1960s and early 1970s is most markedly class-skewed and amounts to at best a sort-of racial trickle down.”11

Reed Jr. argues the ‘old guard’ acts in concert with neoliberal objectives, but he doubts the ‘new generation’ will break from this tradition. BLM’s anointed spokespersons, 12 for Reed Jr., reflect basic liberal positions which are inadequate for contesting today’s capitalist hegemony. “Alicia Garza and Patrisse Cullors,” he says, “understand advancing a political cause as identical with advancing an individual brand.”13 Bruce A. Dixon shares Reed Jr.’s skepticism, asking “to whom are #BlackLivesMatter's leaders accountable, and just where are they taking their ‘movement?’”14

BLM, for Dixon, mirrors the spectacle of Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign promising ‘hope’ and ‘change,’ delivering neither. “Maybe movements nowadays are really brands,” he opines, “to be evoked and stoked by marketers and creators when needed. But it's hard to imagine a brand transferring the power from the wealthy to the poor.”15 Demands for leadership accountability reflect disaffection with BLM’s loose horizontals. Again, I contend that the real debate is not on leaderlessness or horizontals, it is on revolutionary strategy. More specifically, it is an extension of vanguard debates today taking form in appeals for either a class-based political movement or an identity-based one.

#BlackLivesMatter march in Minnesota in August, 2015.

This debate creates, in my view a false, polarity between class politics and identity politics. Framed by philosopher Nancy Fraser, class programs root their political objectives in redistribution while identity-based programs focus on the ‘struggle for recognition’ or representation.16 Attempts are made to locate society’s central oppression where focusing energies on contesting this central oppression is perceived as the most expedient strategy for liberation. Such efforts quickly devolve into what has been labeled ‘oppression olympics,’ which Andrea Smith counters is actually a matter of inadequate analytical frameworks.17 Posing strategic dilemmas, she explains, different groups put forth the need to dismantle a particular form of oppression (seen as most salient to keep the current social system of capitalism intact) prior to other oppressions. Thus, strategies for liberation can ‘run into conflict’ with one another.18

These positions repurpose certain themes within vanguardist theories. Contained within class versus identity frameworks is the tacit argument that some groups are in a better social position to lead a revolution. Characterized by John Brown Childs, “the Vanguard, holds that there is within society a dominant center from which all else flows. To make positive basic changes in society, it is necessary to understand and control this center.”19 The back-and-forth between a class or identity politics analytically parallels vanguardist theory. A class-based vanguard locates capitalist exploitation as society’s central inner logic, whereas an identity-based vanguard may view racial and ethnic oppression as the center. I will take up the argument again below; however, at this juncture it is appropriate to examine the social history of vanguardism in order to understand how we came to this contemporary debate.

An open reading on the history of vanguardism

Discomfort with vanguards stem from their common association with elite and top-down leadership.20 Yet an open reading of vanguard history proves instructive for today’s revolutionaries as it highlights differing inflections beyond the pejorative ‘vanguard.’ Clear distinctions exist between vanguardism espoused by 1930s anarchists (labeling themselves The Vanguard Group) chronicled by historian Andrew Cornell21 and the self-identification with Leninist vanguardism made by Donald Trump’s fascistic chief strategist Stephen Bannon.22 An open social history discovers the cracks23 within vanguard theory and practice. It cultivates a conception of leadership which does not dominate, but provokes awareness and creates entry points (or cracks) for inexperienced activists to enter mass movements.

In his short survey on vanguards, David Graeber contends that modern social theory (generated by Henri de Saint-Simon and Auguste Comte) was born in tandem with notions of vanguardism. Explains Graeber, “Saint-Simon was writing in the wake of the French Revolution and, essentially, was asking what went wrong…How can we do it right?” As a corrective to revolutionary failure, Saint-Simon sketched a vision of future society where “artists would hatch the ideas which they would then pass on to the scientists and industrialists to put into effect.”24 Strict leadership was not a feature of Saint-Simon’s vanguard. Instead, it was led by visionary artists who donned a particular role in world-making. This is the basis for the avant-garde inflection within broader vanguardist theory.

Auguste Comte, conversely, viewed sociology as a discipline capable of improving society through “the regulation and control of almost all aspects of human life according to scientific principles.”25 Graeber contends these positions were eventually reversed, as the Left shifted its self-image to scientists improving society (science being in the form of a Marxian social science), while the Right saw itself as artists mapping out a vision for a new society (as Hitler and Mussolini imagined themselves doing through their respective fascist projects).

Vanguards viewing themselves as scientists, Graeber poses, align with Marxist groups interested in “a theoretical or analytical discourse about revolutionary strategy.” The avant-garde aligns more with political anarchism which “has tended to be an ethical discourse about revolutionary practice.”26 Graeber helps begin to sketch out the contours of vanguardism’s two inflections: an authoritarian approach regulated by ‘science,’ and an artistic (although we’ll discover elitist) approach guided by optimism in creativity as a vehicle for revolutionary energies. Popular discourse conflates vanguardism as necessarily its authoritarian variant, whereas its artistic thread is commonly known as an avant-garde when it is not being forgotten entirely.

Adding more context, Alan Shandro charts vanguardism’s history beginning with the argument made popular by Marx and Engels that revolution should root itself in a working-class movement. Working-class movements could achieve success, claimed Marx and Engels, with leadership provided by the Communist party. Due to their proximity to capital production, the Communist party grasps the significance of material conditions. Informed by this awareness, the party can guide the working-class masses with sound strategy for toppling bourgeois rule. Within the Communist party, argued Marx and Engels, exists a potential “connection between theory and practice in the leadership of the working-class movement.”27 Shandro cautions against interpreting this argument as “an oracular vision” where “the vanguard plays the role of prophet.” Instead, “the formulation is perhaps more reasonably read as an appreciation that placating the bourgeoisie could never advance the workers’ struggle.” Therefore, the vanguard would be responsible for establishing “principles of solidarity on a class foundation and dispelling the illusion of supra-class solidarity.”28 The bourgeoisie, in short, is constituted by fundamentally opposing interests than those of the proletariat.

A degree of malleability is present in Marx’s and Engels’ construct of a vanguard, opening possibilities for avoiding elitist or authoritarian characteristics. Orthodox views on the vanguard, explains Shandro, appear after Marx’s death. In particular, the work of Karl Kautsky promotes the need for enlightened vanguard leadership. An economic determinist, Kautsky posed that since “capitalist production transforms particular struggles into a universal one” the party in capitalism’s most advanced territorial sector is positioned to acquire consciousness able to perceive “the universal interest of the whole working class.”29 The German Social Democratic Party (SPD) became Kautsky’s vanguard, who “as a result of their consciousness…transcend their particular circumstances.” Unsurprisingly, the SPD were “skilled, urban, Protestant, German, male” workers, and since “Socialist consciousness donned the particular lenses of the advanced workers,” the SPD’s universalism conformed to Eurocentric views on capitalist development.30

The working-class and party are further distinguished from each other in Lenin’s What Is to Be Done? and The State and Revolution. A working-class movement threatened bourgeois dominance, but to overthrow the existing world order31 a revolutionary vanguard party “distinct from the spontaneous working-class movement” was needed. To defeat the bourgeoisie, coordinated strategies and discipline are essential. “Shifting circumstances demand that the vanguard readjust theory and adapt practice to account for the shifting terrain of battle.”32 Lenin understood capitalism as a plastic system, the ruling class can maneuver around working-class confrontations. Working-class spontaneity could be fractured, atomized, and ultimately crushed. Revolutionary strategy, therefore, is necessarily complex and must be adaptable to account for capitalism’s disorienting counter-assaults. “Discipline and preparation,” explains Jodi Dean, “enable the party to adapt to circumstances rather than be completely molded or determined by them.”33

Lenin’s distinction between class and party was seen by opponents as “providing a rationale for the subordination of workers to the authority of revolutionary intellectuals.”34 Figures such as Leon Trotsky and Rosa Luxemburg noted the easy slide from Lenin’s vanguard party into a dictatorship, supplanting the organic struggles of the working-class. 35

Today as a term, ‘vanguardism’ more often refers to sectarian habits amongst the Left. This usage, Shandro suggests, became popular during the 1960s in reference to Maoist and Trotskyite organizations. This conception “insinuated that sect-like narcissism was implicit in the very notion of a vanguard party,” affirming objections toward any Leninist vanguard. In contrast, “the term ‘avant-garde’ has been applied to cutting-edge artists or works of art that take a critical stance vis-à-vis the conformism of mainstream art and culture.”36 The avant-garde is seen as capable of provoking the sleeping masses, but does not lead them. An avant-garde “acts out its critically innovative character not really as leadership at all but as a kind of internal exile from the stifling conformism of capitalist society.”37 Yet a distinction remains between the masses and so-called non-conformist critical thinkers comprising the avant-garde.

Vanguard theories are indeed more rich and flexible than commonly held, with potential to be shaped into non-elite and anti-authoritarian concepts. Shandro points to an inference on the vanguard in the Communist Manifesto (Russian edition, 1882). In it, Marx and Engels suggest the character of a vanguard would change if Russia proved to be the battle ground for a proletarian revolution. Such adaptability “denotes [a vanguard as] the first clash of forces, which gives signal for a wider revolutionary explosion.” Instead of oracular foresight, a vanguard is shaped by mass events which provoke revolutionary uprisings. Since an avant-garde instigates non-conformism, a vanguard posed as the first clash of forces can encourage the “fusion of artistic provocation and political commitment.”38 Merging vanguard and avant-garde inflections, in turn, evinces the form of a radical imagination capable of mapping an open utopia.

Who possesses the correct consciousness?

The basis for an anti-authoritarian conception of a vanguard has been established, but other dilemmas in vanguardism remain. A vanguard can be defined as the frontal assault on power initiating proletarian insurgence against the ruling class. Historically, though, vanguardist thought has also been fueled by frustration with prevailing passivity (or apathy) amongst the masses. Accounting for this, vanguards pose that the masses have internalized their oppression. Marx called this ‘false consciousness,’ enabling class to exist simply in itself instead of for itself. Until the proletariat collectively recognize the source of their domination, they will continue to be a marginal class.

Put by anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko, “the greatest weapon of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.” Yet in recognizing the need to raise consciousness, vanguards have often accepted their exclusive ability to access a consciousness perceived as inaccessible to the masses. The oppressed, for these vanguards, have a collective mind.39 Robin D.G. Kelley writes of this trend within the academy, where “students argue that the problems facing ‘real people’ today can be solved by merely bridging the gap between our superior knowledge and people outside the ivy walls who simply do not have access to that knowledge.”40 For vanguards “the people are seen as totally vulnerable. They have no sense of their past, no understanding of the present, and no vision of the future.”41 D.G. Kelley argues vanguards do not actually instill consciousness onto the masses. Rather, “social movements generate new knowledge, new theories, new questions”42 so that collective action raises individual consciousness, not the other way around. I will return to this point later.

Characterized by John Brown Childs, vanguard elitism flows directly from the view of possessing privileged awareness the masses do not. Vanguards “accept the idea of a dominant center in society,”43 which corresponds to their preconceptions on society’s ills and needed medicine. The center is either materialist or idealist, where materialists “seek to control economic power and the structures of science and technology” while idealists “seek to control society’s culture—its philosophy, art, and literature.”44

Who can lead the revolution?

Vanguard theory, in viewing society as having a dominant center, has preoccupied its analysis with locating the best positioned group to lead a revolution. Corresponding to strategic camp’s materialist philosophy and prefigurative camp’s idealist philosophy, the vanguard’s analysis on society’s center flows into arguments over which social subject is closest to power structures. Propelling this analysis is the vanguard’s desire to locate today’s revolutionary agent (i.e. the proletariat, the peasants, etc.). Views oscillate on which social subject is most fundamental for reproducing power, but whatever the subject they are posed as the necessary leader of a frontal assault. Commonly today, in contrast to early vanguard ideas, the argument goes that those most impacted by oppression, by rebelling, are best poised to overturn the status quo. Debates rage over which form of oppression is most salient for maintaining dominant power. The belief that one center is the base of society parallels notions that oppression has a single focal point. In both, elitist attitudes are common, coupled with charges of false consciousness (whether amid the masses or other vanguard groups).

For Marx and Engels, the proletariat (i.e. factory workers) is a revolutionary agent constituted by capitalism’s inner logic. Factory workers, they believed, form the backbone of capitalist economies. The organization of work (Marx called this the ‘mode of production’) generated enough surplus to eliminate material deprivation, and provided a model of social order which could be reproduced on a societal level. In contradictory fashion, capitalist modes of labor discipline the proletariat for efficiency, instilling all the necessary skills and abilities for organizing an egalitarian society. Thus, in a dialectical process, industrial labor sites generate the agents of revolution.

Until recently, I have not understood Marx’s and Engels’ argument. The experience of work, primarily in restaurants, seemed only to train me for obedience; passivity rather than rebellion a typical outcome among service workers. But over the years as I’ve engaged in activism, the idea that work instills revolutionary discipline became less quixotic. During protest actions, for example, quick decision-making is a valuable skill as no amount of premeditation can prepare participants for inevitable changes in scenarios on the ground. Further, the needed planning and strategizing prior to any protest action requires a high degree of self-initiative among organizers. Restaurant work is intrinsically rapid, demanding one to be quick (both mentally and physically), alert, and efficient. If one couldn’t perform tasks in a snap, they stood little chance of surviving in the industry.

After sixteen years of restaurant work, I gained thousands of hours in practice making quick decisions, generating instant strategies to solve problems, and learning self-initiative. Pierre Bourdieu observed, “the work of acquisition is work on oneself (self-improvement), and effort that presupposes a personal cost…an investment, above all of time.”45 Service work inscribes a certain configuration and level of social and cultural capital, albeit one perceived as considerably less valuable than other configurations of capital. 46 After years of being governed by the mantra ‘if you can lean, you can clean,’ my ability to adapt to a given scenario began to appear and feel natural, as though innate.

Marx and Engels recognized that nineteenth-century factories in England were structured for efficiency, which instilled worker discipline, and featured the most advanced technologies for capital production. By virtue of their work, the proletariat learns how to wield the machines which could be appropriated for society’s needs. With both the practice-based discipline and technological knowledge, the proletariat were in the greatest strategic position to organize themselves and seize capitalism’s means of production. Being organized as a class of workers was a condition within capitalism, the proletariat organized as workers needed to transition from this condition into a proletariat organized as a party. Jodi Dean elaborates: “[workers] are already organized as workers in a factory, which enables them to become conscious of their material conditions and the need to combine into unions…the party is necessary because class struggle is not simply economic struggle. It’s political struggle.”47 For today’s restaurant industry (particularly its fast-food sectors), Marx and Engels would note the technologies workers learn to operate, their discipline toward efficiency, and their awareness of assembly-line organization for dividing labor into manageable tasks. Though privately I hate to admit it, my experience of maximal exploitation for the express benefit of a few has probably facilitated my growth as an organizer in more ways than I likely will ever know.

One must concede, however, that where Marx and Engels thought nineteenth-century factories in England provided a glimpse into how to organize an entire society, this does not hold true for today’s restaurants—or any single industry. Call this a problem of scale and complexity. Since the social world is in movement,48 today’s organizational forms cannot be reduced to any single model. Nor is the center of society strictly economic.

Additionally, an emphasis on the primary role of economics intrinsically holds that exploitation is the lynchpin of oppression. Thereby, once class is abolished (and with it exploitation) capitalism is thrown into the dustbin of history and the path toward total liberation is open. Yet, what happens to patriarchy once capitalism is shucked off our collective backs? Will male supremacy end once the class system disappears?

Casting doubt, feminist historian Gerda Lerner argues patriarchy extends as far back as written history. She writes, “the appropriation by men of women’s sexual and reproductive capacity occurred prior to the formation of private property and class society.”49 The extent of women’s subordination to men is difficult to overemphasize. “Women have been systematically excluded from the enterprise of creating symbol systems, philosophies, science, and law,”50 highlighting a history of systematic exclusion and appropriation on the basis of gender, dating long before the emergence of capitalism.

Similar questions hold on the impact ending capitalism will have for domination linked to race, sexuality, and religious identification, or more concretely, white supremacy, cultural imperialism, settler-colonialism, and empire. Oppressions outside exploitation are undoubtedly altered with the abolition of class, but it seems equally true that some or another form of systemic violence, cultural imperialism, marginalization, or powerlessness could emerge after the destruction of capitalist modes of social order.51

Acting on this view, various social movements since the first half of the twentieth-century have splintered off from the primacy of class. Today, in the current popular framework and even in the telling of mainstream history, explicit class political projects are largely relegated to the ‘labor movement.’ Identity-based movements—civil rights, women’s, and LGBTQ movements to list a few—serve a much more prominent role in the public imagination.52 Robin D.G. Kelley, in surveying twentieth-century Black liberation movements, reports on the trend among Socialist organizations to subordinate Black freedom to the class struggle. Critical Black Socialist thinkers grew tired of Socialist parties downplaying the significance of what they called ‘the Negro Question.’ “The European working class,” they charged, “had too often joined forces with the European bourgeoisie in support of racism, imperialism, and colonialism.”53

Black intellectuals, and socialist proponents, such as Ida B. Wells, W.E.B. Du Bois, Claude McKay, and Paul Robeson, challenged the prevailing class orthodoxy within the ranks of Marxist-inspired organizations. They flipped the analysis, arguing that only once white supremacy was dismantled could the class struggle be successfully fought. Therefore, class abolition could not be prior to Black liberation but by necessity must follow the project of dismantling racial marginalization. In the wake of mass disillusionment with the civil rights movement to “achieve all its goals and to deal with urban poverty,”54 criticisms of ‘class reductionism’ took stronger hold. The rise of the Black Panther Party (self-described as the vanguard of the revolution), along with successes by Third World liberation movements, cemented positions against viewing the proletariat as the revolutionary vanguard. For Black revolutionaries at the time, “the uprisings of the colonized might point the way forward”55 for a more robust international revolutionary project.

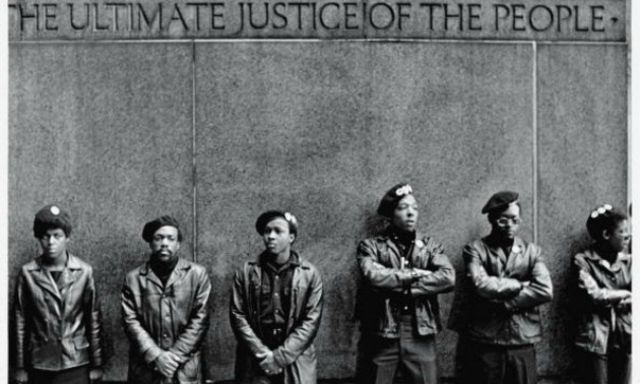

Film still from Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution

“[Third World liberation] movements…were independent of both the white Left and the mainstream civil rights movement” explains Robin D.G. Kelley. “Directing much of their attention to working-class struggles, urban poverty and racism, and police brutality…a vision of global class revolution led by oppressed people of color”56 took shape. However, these liberation movements proved limited as well, and in the U.S. Black Power groups like the Black Panther Party “were so concerned with self-defense…that they devoted little time and energy to the most fundamental question of all: what kind of world they wanted to build if they did win.”57

The weakness of political imagination points to the need for embracing the radical imagination, along with placing open utopia as a foundation for contemporary movements. Black Power offered instances of vision and imagination, but ultimately these groups became encumbered in a fight for gaining political inches. Had they committed to sketching the world they wanted to live in, perhaps this period of radicalism would have endured. Under the weight of a massive assault by the FBI (known as its COINTELPRO program), the bulk of a once powerful Black Socialist movement was effectively destroyed. 58

Contemporary thinkers, such as Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, have issued a clarion call for resurrecting Black Socialist politics. Yamahtta Taylor has also expressed the need to stop framing class and identity as dualistic political projects.

The foibles of the [Communist Party] should not be conflated with the validity of anti-capitalism and Socialism as political theories that inform and guide the struggle for Black liberation…Far from being marginal to the struggles of Black people, Socialists have always been at the center of those movements—from the struggle to save the Scottsboro Boys in the 1930s, to Bayard Rustin’s role in organizing the 1963 March on Washington, to the Black Panther Party’s organizing against police brutality. 59

Open possibilities exist for weaving together a class and identity vanguard project. Offering a way forward, Aimé Césaire wrote “I am not going to entomb myself in some strait particularism. But I don’t intend either to become lost in a fleshless universalism…I have a different idea of a universal. It is of a universal rich with all that is particular, rich with all the particulars there are, the deepening of each particular, the coexistence of them all.”60 | P

-

- ‘Open Utopia’ is a concept I attempted to develop elsewhere. Rather than a utopia that operates as a ‘blueprint’ or preoccupies itself with prefiguring the revolution today at the expense of far-sighted strategic end goals I posed that utopia should neither be prescriptive nor entirely abandon its prefigurative aspirations, but recognize its features will require constant revision, addition, and redirection where broad principles decided on a democratic basis offer a guiding framework for an ‘open utopia.’ Riccio 2017.↩

-

- Howard Zinn perhaps captures the demands of OWS best in a speech before his death, ‘’What, are you a dreamer?’ And the answer is, yes, we’re dreamers. We want it all.’ Zinn 2012, p. 258.↩

-

- I refer to the notion of ‘common sense’ made coherent by Antonio Gramsci, who viewed the project of cultural hegemony as one which imposed its own set of accepted values and norms accepted by the population at large, cementing its power.↩

-

- Dean 2012, p. 210.↩

-

- Jaffe 2013, p. 201.↩

-

- Taylor 2016, p. 168.↩

-

- Taylor 2016 p. 161.↩

-

- Taylor 2016, p. 162.↩

-

- Taylor 2016, p. 158.↩

-

- ‘Black politics’ is defined by Lester K. Spence as a substitute for generic terms like ‘racial politics.’ Black politics refers to ‘the ways different black populations compete over scarce resources, over time, over money, over votes, over public policy, over agenda items, over care, and other resources that have a significant impact on how black communities and the people within them are structured.’ Spence 2015, p. 7.↩

-

- Reed Jr. 2016.↩

-

- Namely he refers to Patrisse Cullors, Opal Tometti, Alicia Garza, and DeRay Mckesson.↩

-

- Reed Jr. 2016.↩

-

- Dixon 2015.↩

-

- Ibid.↩

-

- Fraser 1997, pp. 11-40.↩

-

- Smith 2012, pp. 285-294.↩

-

- Smith specifically refers to the strategic conflicts within women of color communities, but I find her argument to remain equally true when one considers the claims of class-bound political adherents that exploitation is the lynchpin source of all oppression.↩

-

- Childs 1989, p. 3.↩

-

- Most often this conception is attributed to Lenin and his most fervent admirers—the debate over whether Lenin himself was an opportunist, latent dictator, or bottom-up revolutionary is exhaustive. Engaging in this debate risks derailing my purpose here, so I will only make mention of these different positions in passing without taking a firm stance either way, which is genuinely beside the point.↩

-

- Cornell 2016, pp. 113-124.↩

-

- According to journalist Ronald Radosh, Bannon in conversation confessed to being a Leninist since Lenin wanted ‘to destroy the state, and that’s [his] goal too’ (The Daily Beast 2016).↩

-

- Inspired in large part by John Holloway’s body of work, I have argued that capitalism should be understood as an ‘open totality’ where there are ‘cracks’ and ‘ruptures’ in the social order that pose as potential sites for revolutionary strategy.↩

-

- Graeber 2007, p. 306.↩

-

- Graeber 2007, p. 307.↩

-

- Graeber 2007, p. 304.↩

-

- Shandro 2016, p. 440.↩

-

- Ibid.↩

-

- Ibid.↩

-

- Ibid.↩

-

- A world order, according to Lenin, owing to capitalism’s logical development into an imperialist system of globalized exploitation.↩

-

- Shandro 2016, p. 442.↩

-

- Dean 2012, p. 241.↩

-

- Shandro 2016, p. 443.↩

-

- Anarchists also made this charge against Lenin’s vanguard party, finding a particularly clear expression in the essay popularized by Murray Bookchin, Listen Marxists!↩

-

- Shandro 2016, p. 444.↩

-

- Shandro 2016, p. 445.↩

-

- Shandro 2016, p. 444.↩

-

- I am not suggesting that this is the attitude of Biko, but merely noting the predominance of holding a view that one is somehow more enlightened than the masses, and therefore must show them the light of knowledge.↩

-

- Kelley 2002, p. 8.↩

-

- Childs 1989, p. 3.↩

-

- Kelley 2002, p. 8.↩

-

- Childs 1989, p. 4.↩

-

- Childs’ assertion that vanguards take on either a materialist or idealist approach can be approximated onto my distinction between the authoritarian (materialist) and elitist (idealist) tendencies within vanguardism.↩

-

- Bourdieu 1986.↩

-

- Bourdieu identifies four forms of capital: economic, cultural, social, and symbolic. The volume plus configuration of these capital forms, along with one’s social trajectory, determine one’s class position.↩

-

- Dean 2016, p. 253.↩

-

- I’ve argued in a separate piece that the social world, referencing Bourdieu, is a mass accumulation of history where movement (where the movement of capitalist dispossession or resistance activities) is a constant driving factor which creates ‘cracks’ and ‘ruptures’ in the organization of capitalism.↩

-

- Lerner 1986, p. 8.↩

-

- Lerner 1986, p. 5.↩

-

- Iris Marion Young has proposed the above as the five forms oppression takes in contemporary society, in her seminal essay ‘Five Faces of Oppression’ easily accessible online.↩

-

- I do not wish to imply that ‘class’ or ‘identity’ politics operate in separate silos—although sometimes that is unfortunately true. Rather, I find it common to encounter any and all associations of contemporary class politics to be confined to something that labor unions do (as though unions aren’t the collective accumulation of diverse worker identities), and also often coded as a white person phenomenon.↩

-

- Kelley 2002, p. 178.↩

-

- Kelley 2002, p. 62.↩

-

- Kelley 2002, p. 178.↩

-

- Kelley 2002, p. 62.↩

-

- Kelley 2002, p. 108.↩

-

- COINTELPRO also placed the anti-war Left and Socialist groups in its cross-hairs. One would be wise to remember that state and private sector violence is always available as a technique to crush resistance movements—regardless of their commitment to non-violence.↩

-

- Taylor 2016, pp. 204-205.↩

- Quoted in Kelley 2002, p. 179.↩