The Millennial Left is dead

Chris Cutrone

Platypus Review 100 | October 2017

Those who demand guarantees in advance should in general renounce revolutionary politics. The causes for the downfall of the Social Democracy and of official Communism must be sought not in Marxist theory and not in the bad qualities of those people who applied it, but in the concrete conditions of the historical process. It is not a question of counterposing abstract principles, but rather of the struggle of living social forces, with its inevitable ups and downs, with the degeneration of organizations, with the passing of entire generations into discard, and with the necessity which therefore arises of mobilizing fresh forces on a new historical stage. No one has bothered to pave in advance the road of revolutionary upsurge for the proletariat. With inevitable halts and partial retreats it is necessary to move forward on a road crisscrossed by countless obstacles and covered with the debris of the past. Those who are frightened by this had better step aside. (“Realism versus Pessimism,” in "To Build Communist Parties and an International Anew," 1933)[1]

They had friends, they had enemies, they fought, and exactly through this they demonstrated their right to exist. (“Art and Politics in Our Epoch,” letter of January 29, 1938)

The more daring the pioneers show in their ideas and actions, the more bitterly they oppose themselves to established authority which rests on a conservative “mass base,” the more conventional souls, skeptics, and snobs are inclined to see in the pioneers, impotent eccentrics or “anemic splinters.” But in the last analysis it is the conventional souls, skeptics and snobs who are wrong—and life passes them by. (“Splinters and Pioneers,” in “Art and Politics in our Epoch,” letter of June 18, 1938)[2]

— Leon Trotsky

Discard

THE MILLENNIAL LEFT has been subject to the triple knock-out of Obama, Sanders, and Trump. Whatever expectations it once fostered were dashed over the course of a decade of stunning reversals. In the aftermath of George W. Bush and the War on Terror; of the financial crisis and economic downturn; of Obama’s election; of the Citizens United decision and the Republican sweep of Congress; of Occupy Wall Street and Obama’s reelection; and of Black Lives Matter emerging from disappointment with a black President, the 2016 election was set to deliver the coup de grâce to the Millennials’ “Leftism.” It certainly did. Between Sanders and Trump, the Millennials found themselves in 2015–16 in mature adulthood, faced with the unexpected—unprepared. They were not prepared to have the concerns of their “Leftism” become accused by BLM—indeed, Sanders and his supporters were accused by Hillary herself—of being an expression not merely of “white privilege” but of “white supremacy.” The Millennials’ “Leftism” cannot survive all these blows. Rather, a resolution to Democratic Party common sense is reconciling the Millennials to the status quo—especially via anti-Trump-ism. Their expectations have been progressively lowered over the past decade. Now, in their last, final round, they fall exhausted, buffeted by “anti-fascism” on the ropes of 2017.

A similar phenomenon manifested in the U.K. Labour Party, whose Momentum group the Millennial Left joined en masse to support the veteran 1960s “socialist” Jeremy Corbyn. But Brexit and Theresa May’s election did not split, but consolidated the Millennials’ adherence to Labour—as first Sanders and then Trump has done with the American Millennial Left and the Democrats.

All of us must play the hand that history has dealt us. The problem is that the Millennial Left chose not to play its own hand, shying away in fear from the gamble. Instead, they fell back onto the past, trying to re-play the cards dealt to previous generations. They are inevitably suffering the same results of those past failed wagers.

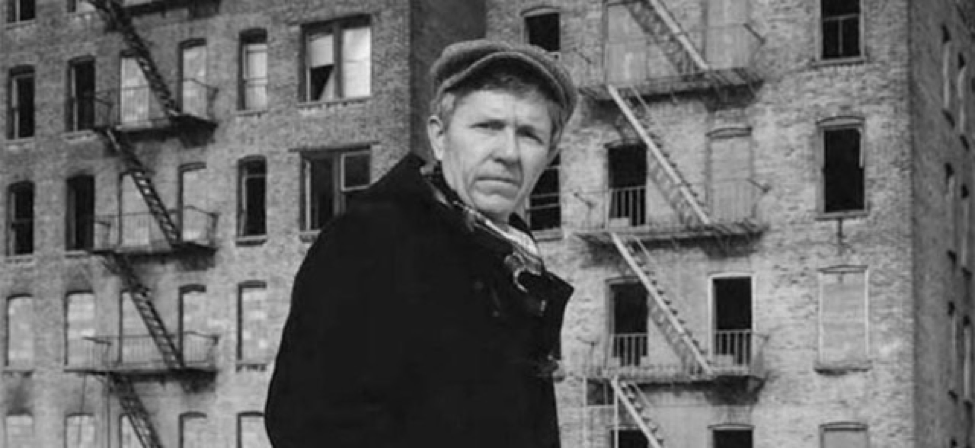

Michael Harrington (1928–89)

Decline

The Left has been in steady decline since the 1930s, not reversed by the 1960s–70s New Left. More recently, the 1980s was a decade of the institutionalization of the Left’s liquidation into academicism and social-movement activism. A new socialist political party to which the New Left could have given rise was not built. Quite the opposite. The New Left became the institutionalization of the unpolitical.

Michael Harrington’s (1928–89) Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), established in 1982, was his deliberate attempt in the early 1980s Reagan era to preserve what he called a “remnant of a remnant” of both the New Left and of the old Socialist Party of America that had split three ways in 1973. It was the default product of Harrington and others’ failed strategy of “realigning” the Democratic Party after the crisis of its New Deal Coalition in the 1960s. No longer seeking to transform the Democratic Party, the DSA was content to serve as a ginger-group on its “Left” wing.

Despite claims made today, in the past the DSA was much stronger, with many elected officials such as New York City Mayor David Dinkins and Manhattan Borough President Ruth Messinger. The recent apparent renaissance of the DSA does not match its historic past height. At the same time, Bernie Sanders was never a member of the DSA, considering it to be too Right-wing for his purposes.

In 2017, the DSA’s recent bubble of growth—perhaps already bursting now in internal acrimony—is a function of both reaction to Hillary’s defeat at the hands of Trump and the frustrated hopes of the Sanders campaign after eight years of disappointment under Obama. As such, the catch-all character of DSA and its refurbished marketing campaign by DSA member Bhaskar Sunkara’s Jacobin magazine—Sunkara has spoken of the “missing link” he’s trying to make up between the 1960s generation and Millennials—is the inevitable result of the failure of the Millennial Left. By uniting the International Socialist Organization (ISO), Solidarity, Socialist Alternative (SAlt), and others in and around the way-station of the DSA before simply liquidating into the Democrats, the Millennial Left has abandoned whatever pretenses it had to depart from the sad history of the Left since the 1960s: The ISO, Solidarity, and SAlt are nothing but 1980s legacies.

The attempted reconnection with the 1960s New Left by the Millennials that tried to thus transcend the dark years of reaction in the 1980s–90s “post-political” Generation-X era was always very tenuous and fraught. But the 1960s were not going to be re-fought. Now in the DSA, the Millennials are falling exactly back into the 1980s Gen-X mold. Trump has scared them into vintage Reagan-era activity—including stand-offs with the KKK and neo-Nazis. Set back in the 1980s, It and Stranger Things are happening again. The Millennials are falling victim to Gen-X nostalgia—for a time before they were even born. But this was not always so.

The founding of the new Students for a Democratic Society (new SDS) in Chicago in 2006, in response to George W. Bush’s disastrous Iraq War, was an extremely short-lived phenomenon of the failure to unseat Bush by John Kerry in 2004 and the miserable results of the Democrats in the 2006 mid-term Congressional elections. Despite the warning by the old veteran 1960s SDS members organized in the mentoring group, the Movement for a Democratic Society (MDS), to not repeat their own mistakes in the New Left, the new SDS fell into similar single-issue activist blind-alleys, especially around the Iraq War, and did not outlive the George W. Bush Presidency. By the time Obama was elected in 2008, the new SDS was already liquidating, its remaining rump swallowed by the Freedom Road Socialist Organization (FRSO)—in a repetition of the takeover of the old SDS by the Maoists of the Progressive Labor Party after 1968. But something of the new SDS’s spirit survived, however attenuated.

The idea was that a new historical moment might mean that “all bets are off,” that standing by the past wagers of the Left—whether those made in the 1930s–40s, 1960s–70s, or 1980s–90s—was not only unnecessary but might indeed be harmful. This optimism about engaging new, transformed historical tasks in a spirit of making necessary changes proved difficult to maintain.

Frustrated by Obama’s first term and especially by the Tea Party that fed into the Republican Congressional majority in the 2010 mid-term elections, 2011’s Occupy Wall Street protest was a quickly fading complaint registered before Obama’s reelection in 2012. Now, in 2017, the Millennials would be happy for Obama’s return.

Internationally, the effect of the economic crisis was demonstrated in anti-austerity protests and in the election and formation of new political parties such as SYRIZA in Greece and Podemos in Spain; it was also demonstrated in the Arab Spring protests and insurrections that toppled the regimes in Tunisia and Egypt and initiated civil wars in Libya, Yemen, and Syria (and that were put down or fizzled in Bahrain and Lebanon). (In Iran the crisis manifested early on, around the reform Green Movement upsurge in the 2009 election, which also failed.) The disappointments of these events contributed to the diminished expectations of the Millennial Left.

In the U.S., the remnants of the Iraq anti-war movement and Occupy Wall Street protests lined up behind Bernie Sanders’s campaign for the Democratic Party Presidential nomination in 2015. Although Sanders did better than he himself expected, his campaign was never anything but a slight damper on Hillary’s inevitable candidacy. Nevertheless, Sanders served to mobilize Millennials for Hillary in the 2016 election—even if many of Sanders’s primary voters ended up pushing Trump over the top in November.

Trump’s election has been all the more dismaying: How could it have happened, after more than a decade of agitation on the “Left,” in the face of massive political failures such as the War on Terror and the 2008 financial collapse and subsequent economic downturn? The Millennials thought that the only way to move on from the disappointing Obama era was up. Moreover, they regarded Obama as “progressive,” however inadequately so. This assumption of Obama’s “progressivism” is now being cemented by contrast with Trump. But that concession to Obama’s conservatism in 2008 and yet again in 2012 was already the fateful poison-pill of the Democrats that the Millennials nonetheless swallowed. Now they imagine they can transform the Democrats, aided by Trump’s defeat of Hillary, an apparent setback for the Democrats’ Right wing. But change them into what?

This dynamic since 2008—when everyone was marking the 75th anniversary of the New Deal—is important: What might have looked like the bolstering or rejuvenation of “social democracy” is actually its collapse. Neoliberalism achieves ultimate victory in being rendered redundant.

Like Nixon’s election in 1968, Trump’s victory in 2016 was precisely the result of the failures of the Democrats. The 1960s New Left was stunned that after many years protesting and organizing, seeking to pressure the Democrats from the Left, they were not the beneficiaries of the collapse of LBJ. Like Reagan’s election in 1980, Trump’s election is being met with shock and incredulity, which serves to eliminate all differences back into the Democratic Party, to “fight the Right.” Antifa exacerbates this.

From anti-neoliberals the Millennial Left is becoming neoliberalism’s last defenders against Trump—just as the New Left went from attacking the repressive administrative state under LBJ in the 1960s to defending it from neoliberal transformation by Reagan in the 1980s. History moves on, leaving the “Left” in its wake, now as before. Problems are resolved in the most conservative way possible, such as with gay marriage under Obama: Does equality in conventional bourgeois marriage meet the diverse multiplicity of needs for intimacy and kinship? What about the Millennials’ evident preferences for sex without relationships, for polyamory, or for asexuality? The Millennials act as if Politically Correct multiculturalism and queer transgenderism were invented yesterday—as if the world was tailor-made to their “sensitivity training”—but their education is already obsolete. This is the frightening reality that is dawning on them now.

Signature issues that seem to “change everything” (Naomi Klein), such as economic “shock therapy,” crusading neoconservatism, and climate change, are sideswiped—ushered off the stage and out of the limelight. New problems loom on the horizon, while the Millennials’ heads spin from the whiplash.

Ferdinand Lassalle wrote to Marx (December 12, 1851) that, “Hegel used to say in his old age that directly before the emergence of something qualitatively new, the old state of affairs gathers itself up into its original, purely general, essence, into its simple totality, transcending and absorbing back into itself all those marked differences and peculiarities which it evinced when it was still viable.” We see this now with the last gasps of the old identity politics flowing out of the 1960s New Left that facilitated neoliberalism, which are raised to the most absurd heights of fever pitch before finally breaking and dissipating. Trump following Obama as the last phenomenon of identity politics is not some restoration of “straight white patriarchy” but the final liquidation of its criterion. The lunatic fringe racists make their last showing before achieving their utter irrelevance, however belatedly. Many issues of long standing flare up as dying embers, awaiting their spectacular flashes before vanishing.

Trump has made all the political divisions of the past generation redundant—inconsequential. This is what everyone, Left, Right and Center, protests against: being left in the dust. Good riddance.

Whatever disorder the Trump Administration in its first term might evince—like Reagan and Thatcher’s first terms, there’s much heat but little light—it compares well to the disarray among the Democrats, and, perhaps more significantly, to that in the mainstream, established Republican Party. This political disorder, already the case since 2008, was the Millennials’ opportunity. But first with Sanders, and now under Trump, they are taking the opportunity to restore the Democrats; they may even prefer established Republicans to Trump. The Millennials are thus playing a conservative role.

Trump

Trump’s election—especially after Sanders’s surprise good showing in the Democratic primaries—indicates a crisis of mainstream politics that fosters the imagination of alternatives. But it also generates illusions. If the 2006 collapse of neoconservative fantasies of democratizing the Middle East through U.S. military intervention and the 2008 financial crisis and Great Recession did not serve to open new political possibilities, then the current disorder will also not be so propitious. At least not for the “Left.”

The opportunity is being taken by Trump to adjust mainstream politics into a post-neoliberal order. But mostly Trump is—avowedly—a figure of muddling-through, not sweeping change. The shock experienced by the complacency of the political status quo should not be confused for a genuine crisis. Just because there’s smoke doesn’t mean there’s a fire. There are many resources for recuperating Republican Party- and Democratic Party-organized politics. As disorganized as the Parties may be now, the Millennial “Left” is completely unorganized politically. It is entirely dependent upon the existing Democrat-aligned organizations such as minority community NGOs and labor unions. Now the Millennials are left adjudicating which of these Democrats they want to follow.

Most significant in this moment are the diminished expectations that carry over from the Obama years into the Trump Presidency. Indeed, there has been a steady decline since the early 2000s. Whatever pains at adjustment to the grim “new normal” have been registered in protest, from the Tea Party revolt on the Right to Occupy Wall Street on the Left, the political aspirations now are far lower.

What is clear is that ever since the 1960s New Left there has been a consistent lowering of horizons for social and political change. The “Left” has played catch-up with changes beyond its control. Indeed, this has been the case ever since the 1930s, when the Left fell in behind FDR’s New Deal reforms, which were expanded internationally after WWII under global U.S. leadership, including via the social-democratic and labor parties of Western Europe. What needs to be borne in mind is how inexorable the political logic ever since then has been. How could it be possible to reverse this?

Harry S. Truman called his Republican challenger in 1948, New York Governor Thomas Dewey, a “fascist” for opposing the New Deal. The Communist Party agreed with this assessment. They offered Henry Wallace as the better “anti-fascist.” Subsequently, the old Communists were not (as they liked to tell themselves) defeated by McCarthyite repression, but rather by the Democrats’ reforms, which made them redundant. The New Left was not defeated by either Nixon or Reagan; rather, Nixon and Reagan showed the New Left’s irrelevance. McGovern swept up its pieces. Right-wing McGovernites—the Clintons—took over.

The Millennial Left was not defeated by Bush, Obama, Hillary, or Trump. No. They have consistently defeated themselves. They failed to ever even become themselves as something distinctly new and different, but instead continued the same old 1980s modus operandi inherited from the failure of the 1960s New Left. Trump has rendered them finally irrelevant. That they are now winding up in the 1980s-vintage DSA as the “big tent”—that is, the swamp—of activists and academics on the “Left” fringe of the Democratic Party moving Right is the logical result. They will scramble to elect Democrats in 2018 and to unseat Trump in 2020. Likely they will fail at both, as the Democrats as well as the Republicans must adapt to changing circumstances, however in opposition to Trump—but with Trump the Republicans at least have a head start on making the necessary adjustments. Nonetheless the Millennial Leftists are ending up as Democrats. They’ve given up the ghost of the Left—whose memory haunted them from the beginning.

The Millennial Left is dead. | P

Further reading

Chris Cutrone, “The Sandernistas,” Platypus Review 82 (December 2015–January 2016); “Postscript on the March 15 Primaries,” PR 85 (April 2016); and “P.P.S. on Trump and the crisis of the Republican Party” (June 22, 2016).

Cutrone, “Why not Trump?,” PR 89 (September 2016).

Cutrone, Boris Kagarlitsky, John Milios and Emmanuel Tomaselli, “The crisis of neoliberalism” (panel discussion February 2017), PR 96 (May 2017).

Cutrone, Catherine Liu and Greg Lucero, “Marxism in the age of Trump” (panel discussion April 2017), PR 98 (July–August 2017).

Pre-Trump

Cutrone, "Vicissitudes of historical consciousness and possibilities for emancipatory social politics today: 'The Left is dead! — Long live the Left!'," PR 1 (November 2007).

Cutrone, “Obama: Progress in regress: The end of ‘black politics’,” PR 6 (September 2008).

Cutrone, “Iraq and the election: The fog of ‘anti-war’ politics,” PR 7 (October 2008).

Cutrone, “Obama: three comparisons: MLK, JFK, FDR: The coming sharp turn to the Right,” PR 8 (November 2008).

Cutrone, “Obama and Clinton: ‘Third Way’ politics and the ‘Left’,” PR 9 (December 2008).

Cutrone, Stephen Duncombe, Pat Korte, Charles Post and Paul Street, “Progress or regress? The future of the Left under Obama” (panel discussion December 2008), PR 12 (May 2009).

Cutrone, “Symptomology: Historical transformations in social-political context,” PR 12 (May 2009).

Cutrone, "The failure of the Islamic Revolution in Iran," PR 14 (August 2009).

Cutrone, Maziar Behrooz, Kaveh Ehsani and Danny Postel, "30 years of the Islamic Revolution in Iran" (panel discussion November 2009), PR 20 (February 2010).

Cutrone, "Egypt, or, history's invidious comparisons: 1979, 1789, and 1848," PR 33 (March 2011).

Cutrone, "To the shores of Tripoli: Tsunamis and world history," PR 34 (April 2011)

Cutrone, “Whither Marxism? Why the Occupy movement recalls Seattle 1999,” PR 41 (November 2011).

Cutrone, “A cry of protest before accommodation? The dialectic of emancipation and domination,” PR 42 (December 2011–January 2012).

Cutrone, “Class consciousness (from a Marxist perspective) today,” PR 51 (November 2012).

Notes

[1] Leon Trotsky, "To Build Communist Parties and an International Anew" (1933), available online at <https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/germany/1933/330715.htm>.

[2] Leon Trotsky, “Art and Politics in Our Epoch,” Partisan Review (June 1938), available online at <https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1938/06/artpol.htm>.