Beyond Social Democracy: popular assemblies, confederal democracy, and internationalism

Howie Hawkins

Platypus Review #90 | October 2016

THE RECENT PLATYPUS PANEL on the “Death of Social Democracy” raised the prospect of a socialist left whose approach is not focused on taking power in capitalist national states, whether through the electoral reformism of traditional Social Democracy or a Bolshevik-style armed seizure, but on building a grassroots-democratic, confederal, and internationalist counterpower that can replace capitalist nation-states with a truly democratic socialism. This prospect was only broached in the critique of Social Democracy. I would like to suggest some perspectives to fill out this prospect.

Jason Schulman began the panel with what are several essential starting points for any serious discussion of what socialists should do after the death of Social Democracy. I would summarize those points as follows:

• Traditional Social Democratic electoral reformism functions as the left wing of capital today. It cannot win or even defend old social democratic reforms anymore. It rationalizes their rollback.

• Settling for a Social Democratic or New Deal welfare state under capitalism leaves the capitalist ruling class intact and in power through its control of the private economy and the capitalist state. That means welfare state reforms are not secure from repeal.

• Winning and securing progressive reforms will take disruptive direct action movements. Demonstrations, strikes, civil disobedience, and other organized disorder are needed to keep a socialist party’s electoral campaigns and elected officials committed to the radical goal of socialism.

• The new socialist movement has to be internationalist in structure and action, not just with words and symbols, because capitalism is, more than ever, globally structured.

• A socialist movement cannot defeat the armed forces of modern capitalist states militarily. Socialists will have to win over the armed forces politically.

I was particularly glad to see Schulman make this last point. Winning over the ranks of the armed forces is an absolutely crucial strategic necessity for socialists. It has been rarely mentioned on the U.S. left since the Vietnam War, when some of us concluded that the most powerful way to resist the war, when our draft numbers were called, was to join the armed forces and organize within. The antiwar movement in the armed forces—including the important civilian-led GI coffeehouses that supported the soldiers’ revolt against the war—is a historical example we must not forget. We need socialists in the ranks and among the officer corps who can lead resistance to imperial wars and repression of domestic socialist electoral and legislative gains. The 1973 coup against Allende in Chile and the 2002 attempted coup against Chavez in Venezuela both illustrate in different ways the importance of both a mass movement backing elected socialists and a base in the armed forces supportive of the movement or at least constitutional requirements for civilian rule.

Schulman uses the British Labour Party’s Jeremy Corbyn to illustrate the limits of social democratic reform as a national as opposed to international project. Christoph Lichtenburg and Brian Tokar use Bernie Sanders to point to other limits of Social Democratic reform. It seeks to ameliorate the problems of capitalism—inequality, imperialism, and so forth—rather than end them with a socialist alternative. Running as a Democrat, Sanders strengthened the Democratic Party by making the party look better than it is. Many disaffected progressives are now back in the party’s pocket, where their votes will be taken for granted and their demands dismissed.

So far, so good. But what socialists should do with this analysis is where the panelists come up short. Their answers stop at brief formulas. For Schulman, it’s building “a genuinely socialist anti-capitalist international.” For Lichtenberg, it’s building an independent mass party of the Left. For Tokar, it’s a “movement of movements” replacing the nation-state with a “confederation of ‘rebel cities.’” William Pelz suggests a similar approach in calling for a “third way” that is neither an electoral nor armed seizure of the capitalist nation-state, but the construction of a new political order modeled on the Paris Commune. Schulman also emphasizes the need for a new political order that replaces the capitalist state with a “genuinely democratic republic” where workers rule through “extreme democracy.”

All of these formulas can be conceived as mutually compatible—and should be in my view. But in discussing how that might be done today, the panelists accept two premises that I think are wrong. One premise is that the U.S. never had a mass socialist or social democratic movement. The other is that the Green Party is not, or is no more, a political tendency that can be a political vehicle for a new socialist politics.

America is not exceptional, the American Left is

One major fault of most American socialist thinkers is that they know more about European socialist history than American. The fact is that left third parties, led by socialists, drove the public policy debate and legislative agenda in the United States from the 1840s to the 1930s. It is only since 1936—when most of the Left and labor went into the Democratic Party under the leadership of the Communists’ Popular Front policy of coalition with the “progressive” capitalists against the fascists—that we have not had an independent mass socialist or social democratic left in America. The Left lost its voice and very identity as an alternative when it disappeared inside the Democratic Party, where self-described socialists became “progressives” who campaign for the election of liberals.

A small independent left has tried to revive independent left politics since the New Left of the 1960s. The so-called New Social Movements around ethnic, gender, and sexual liberation, community organizing, peace, and the environment, were largely absorbed by the Democratic Party and the non-profit industrial complex around it. These movements' elites have been integrated at the level of the professional classes, while their working classes are increasingly segregated into occupations and communities suffering from steadily growing economic inequality, hardship, and isolation from opportunities. The Green Party is the only independent political party initiative coming out of the New Left movements to have sustained itself for more than three decades over many election cycles. But despite hundreds of local elected officials and some notable presidential runs by Ralph Nader, it has not been strong enough to date to force the two-corporate-party cartel to respond to its demands.

A brief review of the 1840s to 1930s period of independent left politics is in order to show that America is not exceptional in having had no significant socialist or labor party. It is the American left that is exceptional in having abandoned independent politics in the 1930s.

In the antebellum period, a direct line of activists formed Workingmen’s parties, then the Liberty Party, the Free Soil Party, and finally the Republican Party. This political lineage, which included many Red ’48er exiles from failed democratic and social revolutions in Europe of 1848, helped make slavery (“free men”), land reform (“free soil”), and cooperative production (“free labor”) issues the Whigs and Democrats could not avoid., Marx and Engels’ in The Communist Manifesto identified the National Reform Association, the principle land reform organization, as their allied “Agrarian Reformers in America.” The National Reform Association’s secretary, Alvin Earle Bovay, gave the Republican Party its name at a party convention in 1854 in Ripon, Wisconsin, which grew out of the utopian socialist community of Ceresco. The Republicans, of course, rose from third party, to second party, to first party over the course of the 1854 to 1860 elections.[1]

After the Civil War, a series of populist farmer-labor parties—Labor Reform, Greenback-Labor, Anti-Monopoly, Union Labor, People’s—made the money question the central issue as both the Democratic and Republican parties became hard-money, gold-standard parties. In opposition to private bank notes backed by the deflationary gold standard, the populists demanded an expansionary monetary policy in the form of a democratically controlled public currency of U.S. notes, or greenbacks, in order to grow the money supply in concert with the growth in commerce.

Capitalist enterprises were shifting from family dynasties to corporate forms whose share ownership cut across an increasingly class-conscious capitalist class, interested in replacing cutthroat competition with shared monopolies. The Money Trust was one of many shared monopolies the populists fought, including the railroads, the telegraph and telephone companies, and the farm equipment manufacturers and suppliers.

The populists fought back with a cooperative and socialist counter vision. One of the bibles of the movement was Laurence Gronlund’s The Cooperative Commonwealth: An Exposition of Modern Socialism (1884), which popularized in the American vernacular, before Marx’s Capital was translated into English, Marx’s analysis of surplus value, of the nature of exploitation, and of capitalism’s tendencies toward monopolization and overproduction crises. The populists called for government ownership of railroads, telegraph and telephone utilities, a federally-backed “subtreasury plan” to underwrite farmers’ cooperatives, labor reforms like the eight-hour day, and democratic demands like black voting rights and the direct election of Senators.

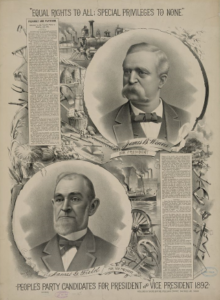

The populists ran to win, not just protest. In the 1878 mid-term election in the wake of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, the Greenback-Labor Party won over one million votes, 14 seats in Congress, and many state and local offices. The Greenbackers transcended post–Civil War sectionalism by receiving, for example, 34.4 percent of the vote in Maine and 23.8 percent of the vote in Mississippi. They followed that up with a presidential campaign in 1880 in which candidate James Baird Weaver ran to restore Radical Reconstruction in the South in the face of the armed militias of the Democratic Party whose slogan was “white supremacy.”[2] Weaver won only 3.3 percent of the presidential vote in 1880, but would go on to win nine percent, over one million popular votes, and 22 electoral votes as the People’s Party presidential candidate in 1892.

People's Party campaign poster from 1892 promotes James Weaver for President of the United States. The party disappeared after the election of 1896, absorbed for the most part into the Democratic Party.

These farmer-labor populist parties were the American counterparts to the rising socialist parties in Europe. Their peak votes of over one million in 1878 and 1892 were comparable to the German and French socialist parties of that era. Those million vote peaks for an independent left were hit again by Socialist Party candidates Eugene Debs in 1912 and 1920 and Norman Thomas in 1932. The class-conscious struggles and strikes of slaves, labor unions, and farmer’s organizations from the Civil War on through the whole Gilded Age were more massive and militant than their counterparts in Europe, and faced more violent opposition from corporate goons and state militias.

The People’s Party famously committed political suicide by cross-endorsing in 1896 the Democrat, William Jennings Bryan. Bryan completely discarded the populist critique of corporate capitalism and its vision of economic cooperation. With the backing of the silver mining trust, notably mine owner and newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, Bryan promoted the free coinage of silver while discarding the populists’ radical program of a democratically-controlled public Greenback currency, black voting rights, and public ownership of railroad, telegraph, and telephone industries.

In the wake of the People’s Party demise, former populists and other socialists then formed the Social Democratic Party of America in 1898, which became the Socialist Party of America in 1901. Hundreds of Socialists were elected to local, state, and congressional offices over the next few decades. The Socialists made labor rights, social insurance, and public enterprise unavoidable topics in elections and public policy debates and many Socialist reform planks were adopted, albeit in diluted forms, during the New Deal era.

The point of this historical sketch is to show that America is not an exceptionally hard place to build a mass-based socialist movement. We had them for over a century. What is exceptional is that our Left abandoned the first principle of socialist politics—political class independence—when it largely went into the Democratic Party in 1936.

Political independence is what the socialist movement learned from the Revolutions of 1848. The pattern in those revolutions was that the workers’ and small farmers’ erstwhile allies in the struggle with the old landed elites for democratic and economic reforms, the professional and business middle classes, abandoned them once they received concessions from the old regime. The same dynamic is at work today when the working class movements and institutions largely rely on the Democrats: They get nothing but taken for granted, because the Democrats have their votes in their pockets.

The Socialist Party of America relearned the lesson of political independence from the debacle of fusion in the populist movement. It put into its party constitution a ban on cross-endorsements with capitalist parties.

Why it took until the Socialist Party for the American left to adopt independent political action as a principle is rooted in its unique history. In America, the franchise was justified in universalistic terms from the start. In Europe, workers had to fight for it. From the American Revolution and before, America's landed and business elites supported a popular electoral franchise. In New England, where a majority of the adult male population (about 70 percent in Boston in 1776) that had some taxable property—farmers, merchants, and artisans—exercised their franchise in directly democratic town meetings. Though initially extended only to propertied white males, because political rights were articulated in universalistic terms, over the course of American history other groups were able to win the franchise for themselves. In other industrially developing countries, workers and peasants had to form their own independent labor parties to fight for the vote and social reforms against the new business elites as well as the old landed elites. The nature of that fight made independent political action by the working class a principle for socialists, not just a contingent tactic. In America in the populist era, fusion politics competed with independent politics until the debacle of 1896.

The missing mass-membership party

The Socialist Party of America also learned another lesson: that to have a working-class party that is democratically accountable to its members and has the financial resources it needs, the members have to agree to a statement of principles, support the party with dues, and participate in a local branch. This mass-membership party structure was an invention of the socialist left in Europe in the latter third of the 19th century. It was how they challenged the older parties of the landed and business elites for power. Except for the Socialist Party of America, which peaked at a membership of 118,000 in 1912, the American left has failed to build this kind of mass party.

The reason that fusion kept coming up in the populist parties is that the they did not base their conventions on delegations from the mass-membership organizations that supported them, such as the Grange, Knights of Labor, Greenback Clubs, and Socialist Labor Party locals in the case of the Greenback-Labor Party, or the northern, southern, and colored Farmers’ Alliances and the Knights of Labor in the case of the People’s Party. Instead, in the convention tradition invented by American political parties in the 1830s, the populists made open calls to precinct caucuses, which would elect delegates to county conventions, and then state and finally national conventions. The problem was that anybody, no matter what their politics, could participate in this convention process. Opportunists from the major party that was the minority party in its region (Republicans in the South, Democrats in the North) flooded populist conventions with proposals for fusion campaigns. Where the popular base of the Populist Party was not well organized, fusionists tended to prevail.

The Socialist Party of America argued that its membership convention system was more democratic than the new voter registration and primary system that corporate-backed reformers introduced in the Progressive Era.[3] While the Progressives argued that primaries were more democratic than the old boss-controlled conventions of political machines, they were also concerned that the Socialists were actually building an organization and taking power through elections in many cities and towns. The New York State Legislature said as much in 1920 in justifying its expulsion of five Socialists elected to the Assembly in 1918 and re-elected in a subsequent special election to replace them. The Joint Legislative Committee Investigating Seditious Activities said the Socialists were not a political party (i.e., a list of voters kept by the state to determine who could vote in a party’s primary), but “an organization” that required political agreement and dues of its members.[4] The last thing the top-down corporate-backed Democrats and Republicans parties wanted was workers organized politically into their own party. They wanted professional elites managing parties and government from the top-down like the modern corporation was managed. The Socialists argued that their deliberative process and accountable structure was more democratic than the primary system, where atomized voters choose among candidates pre-selected by moneyed elites.

It is clear in retrospect that the Socialists were right. The introduction of state-managed party registration rolls and corporate-elite financed primary elections between 1899 and 1920 corresponded also to the introduction of barriers to registration such as poll taxes, literacy tests, and violent intimidation that served to disenfranchise blacks and poor whites in the south and the immigrant workers in the north.[5] At the turn of the century, as European Social Democracy was consolidating the universal franchise and using it to contest for state power, the southern planter and northern business elites were successfully disenfranchising much of the American working class.

The national turnout of voting age citizens in presidential elections was 70 percent to 80 percent in the 19th century. It dropped steadily from 79 percent in 1896 to 49 percent in 1920. The turnout has fluctuated between about 50 percent and 60 percent for the last century. It rose somewhat to about 60 percent during the New Deal/Great Society era between the 1930s and 1960s when reforms beneficial to working class people were on the agenda. Since the 1970s and bipartisan neoliberalism, the working class vote has declined again and the turnout in presidential elections has been closer to 50 percent, except for the Obama bumps to 62 percent in 2008, and 57 percent in 2012.

So we have lived for a century now with the problem that the natural working class base of a left party does not vote much. There are institutional reasons for this low voter turnout, such as voter registration that requires the initiative of voters in the U.S. In most other nations, the government takes the initiative to register its citizens for elections. Since the 2013 U.S. Supreme Court decision gutting the pre-clearance provision of the Voting Rights Act, many states have instituted identification requirements for registration and voting itself. This too suppresses working class votes.

But I would argue that the biggest reason for low turnout among working class voters is not institutional barriers, nor is it “apathy” as so many commentators assert. It is disgust with a two-party system that does not speak to the needs of, and cannot relate to, working people. A close look at who voted for the supposed working people’s champion in each major party this year—Sanders in the Democratic Party, Trump in the Republican Party—shows that workers are still mostly not voting. Based on my experience in electoral campaigns, as a candidate and as a canvasser for other candidates, working people feel the two parties do not care about them, do not know them, and cannot even see them.

It is the absence of a pro-worker independent left party that accounts for the low voter turnout of workers. The institutional barriers to voting contribute to the difficulty of building such a party. But that is not an excuse for the Left not to build its own party.

Prospects for the Green Party

Could the Green Party reach working people and build a mass-membership party of the Left? I think it could. But let us first dispense with some of the panelists’ mistaken ideas about the Green Party.

Lichtenberg says the Greens are not focused on workers. Nonsense. Greens talk to workers whenever they run electoral campaigns, which I recommend to every socialist to get beyond singing to the choir. Greens recruit workers in those election campaigns. I would like to introduce Lichtenberg to the members of the Teamsters, Steelworkers, Ironworkers, Sheet Metal Workers, Teachers, Nurses, Communications Workers, Electrical Workers, Food and Commercial Workers, and Farmworkers unions in my Green Party local in Syracuse, New York. We may not be typical of Green locals, but I find that Green locals tend to be more composed of working class people in communities compared to socialist groups that tend to be more composed of middle class professionals on college campuses.

Lichtenberg also says the Greens are not and never were anti-capitalist. In fact, the Greens were born out of the death of Social Democracy. The Greens in Germany were the left alternative to Social Democratic cold-war militarism and welfare-state capitalism. The German Green’s success in electing 35 members to the German Bundestag in 1983 sparked the formation of Green parties around the world where the Social Democracy (or the New Deal Democrats in the U.S.) presented the same problems for the movements growing out of the New Left of the 1960s. The Green Party in the U.S. has always had a socialist left. We have been patiently explaining the socialist analysis of wage labor as exploitation, of competitive endless accumulation as incompatible with ecological sustainability, of the symbiotic growth of capitalism and racism, of the imperialism that competitive accumulation spawns, and so forth. Socialists are now the dominant tendency in the American Greens, as evidenced by the overwhelming support for the adoption of an anti-capitalist platform plank at the 2016 Green Party convention that calls for “eco-socialism” and a “cooperative commonwealth.”

On July 27, 2016 during the 2016 Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia, presumptive Green Party presidential nominee Jill Stein speaks with "Black Men for Bernie," supporters of former Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders. (Photo: Getty)

Lichtenberg says the Green Party movement internationally was never a social democratic movement. That assertion cannot explain why, for example, the Green Party of England and Wales grew explosively in the post Great Recession years by keeping alive the social democratic reforms the Labour Party had abandoned under its pre-Corbyn leadership. The Green movement is a mixed bag like the socialist movement is. Realo Greens in Germany imposing austerity as junior partners in coalition with the Social Democrats no more define Green politics than Social Democratic austerity policies, or Stalin’s repressive policies, define socialist politics.

The Greens remain a mix of what might be called progressive populists along with socialists. What is most important is the class independence of all Greens from the corporations and their political representatives in the Democratic and Republican parties. As Engels argued to his Marxian Socialist Labor Party correspondents with respect to Henry George’s 1886 Labor Party run for mayor of New York City, working class political independence was the crucial step; the socialist content of the program will come in time from experience in fighting for working class interests.[6] The Green Party in the U.S. has been evolving along these lines.

That is why Tokar’s generalities about the Green Party in the U.S. are so wrong. He generalizes from his own Vermont experience, where the organized Greens did leave the field during the Nader campaigns. The opposite happened in all other states where the Greens were organized. Nader brought in new layers of activists. To say that the Vermont exit was because Nader, or the Green Party, lost interest in giving voice to social movements in elections is just wrong. Nader’s presidential campaigns gave voice to the demands of movements for fair trade, global justice, renewable energy, Palestinian rights, ending the wars in the Middle East and other issues that found no expression in the major parties. Giving voice to social movements, particularly the hardest hit so-called frontline communities, is one of the missions of Jill Stein’s current Green Party presidential campaign.

Nader’s innovative campaign in 2000 pioneered the online networking, information sharing, mobilizations and contributions, as well as the campaign super-rallies, that Dean, Paul, Obama, Sanders, and others built upon in subsequent campaigns. Far from representing a turn to the right and conventional electoral politics, Nader did more to bring class politics to the Greens in 2000 than anyone has before or since. Nader centered his 2000 campaign on corporate power and economic class issues. When the Greens were split in 2004 over whether to run a “safe states” campaign to help Kerry defeat Bush or an independent campaign against both pro-war corporate candidates, Nader continued his focus on class issues as well as the anti-war demands with his independent run with longtime socialist Peter Camejo as his running mate. Most Greens who worked on the Nader-Camejo campaign remain active in the Green Party today.

To say, as Tokar does, that Nader and subsequent Green candidates like Stein left nothing in the wake of their campaigns is to dismiss the credibility with masses of people that Nader’s reputation as lifelong people’s advocate gave to the Greens. It is to dismiss the lists of supporters local Greens were able to develop and then use to continue organizing after the campaigns. Every serious organizer knows how important lists of supporters are. Tokar also disregards the very tangible asset of state ballot lines the campaign won in many states with presidential votes. Those ballot lines enabled Greens to run local campaign in subsequent years in many states.

Tokar is on to something, however, when he says “with the Nader campaigns in 1996 and 2000, the existing Green networks were taken over by tendencies with mainstream electoral ambitions that pitted them against the more left-wing voices within the Greens.” What happened in those years is that the national Green Party structure was changed from a mass-membership party structure of dues-paying members organized in local chapters into a party structured like the Democrats and Republicans, as a federation of state parties with no direct national membership, dues, or structure of direct accountability to the rank-and-file members. Instead, grassroots supporters are an atomized base of supporting voters indirectly represented by insiders on party committees and campaign organizations.

That change was a win for the liberals against the socialists in the Green Party. The liberals thought that the platforms voted through by the delegates of the rank-and-file locals earlier in the 1990s were too socialistic. They did not want to run for office on such radical platforms. They wanted a more top-down structure that cut the rank-and-file members in the locals out of national decision-making, which became their federation of state parties structured around state election laws governing primaries rather than around a grassroots-democratic structure of organized locals.[7] The change in structure largely defunded the national Green Party organization, rendering it incapable of providing much support for local and state party organizing. So the level of party organization varies widely from state to state based on the initiative and capacity of local organizers.

Tokar and his Vermont comrades left after the change in structure was made. Most left Greens stayed, kept working, and the fruit of their work is a Green Party that is the only left political party with a national electoral presence and is programmatically to the left of where it was in 2000. It may not presently have an effective national structure to support local organizing, but there is a base of organizers and activists that have kept the party going across the country.

If the Green Party is to realize its potential, it will need to go back to the mass-membership party structure in order to fund organizers who can support local and state party development and, just as important, to give the party’s grassroots members local organizations through which they can participate in shaping the party’s policies and activities. Discussions about restructuring in this manner are underway today in many state parties and the national party.

The Green Party also needs to get back to what Tokar alludes to when he mentions the more “holistic strategy” of the early Greens when educational and cultural projects, issue campaigns, cooperatives, and labor organizing were pursued alongside with, or in preparation for, electoral campaigns. While European Social Democracy was known for its socialist cultural milieu in affiliated unions, cultural clubs, and cooperatives, the American left of the populist and early socialist era was also strong in this era, from the populists’ large encampments evangelizing their social message in the manner of religious revivals to the unions, housing cooperatives, and educational projects of Socialist Party chapters.

Internationalism and popular assemblies

Thus far I have argued three points about the path for American socialists beyond the death of Social Democracy:

• It is the broad Left’s abandonment of independent working class politics since 1936, not some American exceptionalism rooted in our political institutions and culture, that best explains the absence of a mass party of the Left.

• An independent left party must be a mass-membership party of dues-paying members organized into activist locals, not a copy of the state-regulated top-down registration/primary election party structures of the Democrats and Republicans.

• The Green Party could potentially be that independent left party.

I agree with Lichtenberg that the “subjective factor” is what is missing, that the American left needs to focus on building independent mass working-class party instead of disappearing into reform Democratic campaigns.

The two most important ideas in terms of the program of such a party to come out of the panel were internationalism and a radically democratic new political order.

Shulman's call for internationalism must be embraced. In addition to the type of internationalist economic program needed that Schulman indicated in his critique of Corbyn, the knee-jerk anti-interventionism of most of the American left and peace movement is isolationist, not internationalist. The American left had no qualms about intervening on the side of the Spanish Republic, or the Spanish revolution, in their fight with Franco in 1936-1939.[8] But today, for example, most of the American left has opposed U.S. military intervention in Syria without taking up the difficult question of how to support the democratic revolutions in Kurdish Rojava or Arab Daraya. This failure to act in solidarity with democratic revolutions has to change if the American left is to be internationalist in action and therefore up the task of transforming global capitalism.

Internationalism requires international organization that develops a common program and action. The Greens have a loose international, the Global Greens Coordination, with affiliated parties organized in four continental federations (Africa, Americas, Europe, Asia/Pacific). Most of the parties send representatives who can pay their own way rather than who are sent with the support of their party’s funding, which obviously limits who can participate in continental and global Green meetings. It will take the consolidation of member-funded mass parties in more countries before the Global Greens Coordination is fully representative and accountable. The Coordination is now more of a talk shop for issuing resolutions than an organization with a comprehensive common program and effective international campaigns. But it is a beginning that could evolve—no doubt in conjunction with other left socialist tendencies internationally and in diverse countries—into an international left federation that matters in global politics.

Schulman (“extreme democracy,” “genuinely democratic republic”), Tokar (“confederations of rebel cities”), and Pelz (“example of the Paris Commune”) seem to converge around the notion that the Left should not focus on capturing the existing capitalist state by parliamentary or insurrectionary means, but on moving toward radically democratic alternative from the bottom up that can replace the capitalist state.

Tokar cites Murray Bookchin's writings on confederations of popular assemblies and notes how the Kurds of Rojava are consciously using Bookchin's approach to build a confederal democracy based on popular assemblies in the midst of the civil and proxy war in northern Syria.[9] In the U.S., as Bookchin often urged the Greens to do in the 1980s and 1990s, we can run for municipal office on a program that includes the rewriting of municipal charters to place political power in the hands of the citizens assembled in neighborhood or town meetings and aims to link up these democratized municipalities in confederations to coordinate public affairs across regions from the bottom up. Bookchin summarized this program with the slogan, “Democratize Our Republic and Radicalize Our Democracy.”[10]

When Pelz cites the Paris Commune, I assume he is referring to its radically democratic structure of a city council composed of mandated and recallable delegates of the people in their neighborhood assemblies. The Paris Commune appealed across France for a “Commune of Communes,” a confederation of radically democratic municipalities. I would argue that an independent left that can go beyond Social Democracy should make this democratization and confederation of local governments a central component of its program along with social, economic, environmental, and anti-imperialist demands. If we are going to replace the capitalist state with a real democracy, we need to build it from the bottom up as we gain power from the bottom up. We will need to build this radically democratic and federated power starting at the local level in order to build the mass participation, institutional power, and experience needed to replace the national state and global corporations with a truly democratic socialism. |P

[1] Mark Lause, Young America: Land, Labor, and the Republican Community (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005), 1.

[2] Mark Lause, The Civil War's Last Campaign: James B. Weaver, the Greenback-Labor Party & the Politics of Race & Class (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2001).

[3] Arthur Lipow, “Direct Democracy and Progressive Reform,” in Arthur Lipow, Political Parties and Democracy (Chicago: Pluto Press, 1996).

[4] Joint Legislative Committee Investigating Seditious Activities, New York State Legislature, “Revolutionary Radicalism: Its History, Purpose and Tactics with an Exposition and Discussion of the Steps Being Taken and Required to Curb It,” April 24, 1920: 510.

[5] Frances Fox Piven and Richard A. Cloward, Why Americans Don't Vote (New York: Pantheon Books, 1989).

[6] Engels to Friedrich Adolph Sorge, Karl Marx Frederick Engels Collected Works, Vol. 47 (New York: Progress Publishers, 1995), 532.

[7] Howie Hawkins (ed.), Independent Politics: The Green Party Strategy Debate (Chicago: Haymarket, 2006), 23–26.

[8] Thanks to Bill Fletcher for making these points about isolationism vs. internationalism on the left today and in the 1930s during a recent discussion about the crisis in Syria.

[9] Martin O'Beirne, “Ecosocialism Against ISIS–A Salute to Murray Bookchin,” available online at <http://www.kurdishquestion.com/oldsite/index.php/insight-research/ecosocialism-against-isis-a-salute-to-murray-bookchin/1267-ecosocialism-against-isis-a-salute-to-murray-bookchin.html>.

[10] Murray Bookchin, The Next Revolution: Popular Assemblies and the Promise of Direct Democracy (New York: Verso, 2015).