Emancipation in the heart of darkness: An interview with Juliet Mitchell

Sunit Singh

Platypus Review 38 | August 2011

On November 23, 2010, Sunit Singh conducted an interview with psychoanalyst Juliet Mitchell at Jesus College in Cambridge. Although Professor Mitchell’s rehabilitation of Freud is well chronicled, the attempt in “Women: The Longest Revolution” (1966)[1] to rescue the core content of the Marxist tradition—its emphasis on emancipation—remains unexplored. What follows is an edited version of the interview.

Sunit Singh: The sociologist C. Wright Mills, in an open letter to the editors of New Left Review in 1960, exhorted the still inchoate “New Left” to reclaim an ideological space for socialism over the chorus of liberal commentators proclaiming “the end of ideology”—the idea that there are no more antagonistic contradictions within capitalist society. Post-Marxist rhetoric, as Mills identified, was expressive of the disillusionment with the Old Left, which was itself weakest on the historical agencies of structural change or the so-called subjective factor. Yet, if the Old Left was wedded to a Victorian labor metaphysic, Mills forewarned, the New Left threatened to forsake the “utopianism” of the Left in its search for a new revolutionary subject.[2]] How sensitive were later members of the editorial board of the New Left Review, after Perry Anderson took over from Stuart Hall in 1962, to such injunctions? And to what extent was the project of socialism implicit in “Women: The Longest Revolution” (hereafter referred to as WLR)? Five decades on, where does that project presently stand? What happened to “socialism”?

Juliet Mitchell: I came into direct contact with the New Left Review earlier than the mid-60s, partly through other work I was involved in. I was also a student in Oxford, where we were the originating group of the New Left. Perry [Anderson] and I married in 1962 and lived in London, although I worked in Leeds. The north of England, with Dorothy and Edward Thompson in nearby Halifax, was a centre for the older New Left.

Back then I was planning to write a book, which never saw the light of day, on women in England. It was a historical sociological treatment of the subject. We were driving to meet up with friends and colleagues who ran Lelio Basso’s new journal in Rome when the manuscript was stolen with everything else from our car. I had a bit of a break before I returned to “women.” WLR came in the mid-60s. The timing of the gap and the reluctance to re-do what I had done led to a considerable change in the way I looked at the issue. This relates to your question about C. Wright Mills and ideology. I think when we took over from Stuart Hall the distinction of what separated us from the preceding group was the conviction of the importance of theory over or out of empiricism.

So was I aware that in my use of “ideology” in WLR I was also picking up on C. Wright Mills’s sense of utopianism? Well, “yes and no” would be my answer. For C. Wright Mills, “ideology” read “theory.” However, it was exactly this shift that opened up the importance of ideology. But while reading and admiring C. Wright Mills, our quest led us directly to Althusser’s work. We were in what Thompson later criticized as Sartrean “treetopism” We met with the equipe of Les Temps Modernes in the early 60s. De Beauvoir, with her brilliant depiction and analysis of the oppression of women, at that stage saw any politics of feminism as a trap. Instead she took the classical Marx/Engels line that the condition of women depends on the future of labor in the world. Together with Gérard Horst, who wrote under the name André Gorz, we had a cultural project in London, which, in addition to the magazine, we hoped to share with them. We didn’t want to be imitative, but nevertheless wanted to be engaged with particularly French New Left struggles. The Algerian War was, of course, terribly important. We were urgent for an end to the British isolationism with which the anti-theoretical stance was associated. Then in 1962 some of us went to the celebrations for Ben Bella in Algiers. With Gisele Halimi and Djamila Boupacha this was a background to the left women’s movement that was shortly to emerge. There was also the issue of our relationship to the Chinese Cultural Revolution. That is the background to WLR. And, “no,” in the sense that when I use Althusser, as I do in WLR, it may seem as though I am also picking up on C. Wright Mills’s assertion of the importance of ideology, but really the stress on ideology had more to do with the search for a new theoretical direction that was linked to contemporary French thought. What Althusser offered me through his re-definition of the nature and place of ideology is the overwhelming and now obvious point that sexual difference is lived in the head.

I have never been a member of a party or a church or sect, growing up as I had in an anarchist environment, but I worked actively within the New Left, and then in the women’s movement, before training and practicing as a psychoanalyst. I have had to be pretty “utopian,” as an underpinning to my “optimism of the will,” first about class antagonism, then about women, then about Marxism as dialectical and historical materialism and, ironically, nowadays with the new versions of empiricism, about the theory of psychoanalysis.

SS: Your answer hints at the ways in which the New Left saw itself as new, as against the Maoists, other feminists, and presumably also in relation to the Trotskyists. You were critical of these other tendencies. A pithy passage from Women’s Estate reads, feminist consciousness is “the equivalent of national chauvinism among Third World nations or economism among working-class organizations,” that on its own it “will not naturally develop into socialism nor should it.”[3] Furthermore: “The gray timelessness of Trotskyism is only to be matched by the eternal chameleonism of Western Maoism.”[4] From there the text went on to say that what was needed was to deepen the Marxist method even if it meant rejecting some of the statements made by Marx and Marxists. Was that the task in WLR? Does the same challenge remain today for the Left? How did the ways in which the New Left understood and dealt with this methodological challenge affect the situation for a future Left?

JM: I reread WLR, which I haven’t done for years, because you were coming. I was quite impressed by the shift that it represents from the book that never was, but I was also slightly unmoved by it. It does reflect that overall moment in the entire shift of the New Left from historical research into theory, so what we need to ask is, what happened to ideology? I think, getting back to utopia, that the conception of utopianism melded into the women’s movement. The questions of the longest revolution were: What is the hope? Where is the utopianism? For Engels, there was the utopianism of the end of class antagonism, but what were we to do with that? This might come as a shock, but I never actually stopped thinking of myself as a Marxist, even after other friends on the New Left had stopped identifying themselves as such.

For us, in the 1960s, Marxism was not out there as “Marxism.” One was also self-critical by then, the whole relationship to China had to be re-examined rather as earlier Marxists had to take stock of their relationship to Stalin. What everybody seems to forget is that socialism was foundational for the women’s movement and those of us who were and still are on the Left understood where we had to expand it intellectually, so that is where I took it in WLR. I think of Marx much as I might think of Darwin or Freud in some senses. I think that when you use them, it’s not that you stick within the terms that they set (after all, you are in a different historical epoch, you are in a different social context, and you are posing different questions). Giant theorists such as these impinge on us with their method, not in the narrow sense of methodology, but in their way of approaching the question.

Lately, I keep encountering this belief that where other radicalism was over after 1968, women’s liberation arose out of it. This is not so and is poor history. Women’s liberationists, now called feminists, were active as such in creating ‘68. Feminism continued gaining strength thereafter. Raymond Williams considered the women’s movement the most important one of the last century. The student movement ended, the worker’s movement ended—I am not playing them down—the black movement also ended. The women’s movement was what happened to 1968—it went on. For me, what matters about the women’s movement is the Left; it’s not that it is attached to the Left, it is the Left. Of course at a time when the Left is not very active, conservative dimensions of feminism will flourish and feminism will be misused. It is not the first political movement to suffer these collapses!

SS: I suppose my question, then, is: What happened to the women’s movement?

JM: What happened to it?…Well, I think that when the conditions of existence, the relationship between women and men, achieve a new degree of equality, one comes up against a certain limit. Where first wave demands were dominated by the vote, I suppose we were dominated by the demand for equal work, pay, and conditions. Here our head hit a ceiling, and not a glass ceiling, a concrete one. Feminism from that moment has headed off to the hills to rethink what needs to be done politically. It is, as Adorno says, like putting messages in a bottle. I will remain in the hills until the streets, where there is still radical work going on, welcome me back. That is where I would like to be. But now is not the moment for that; we are plateauing. The fight against women’s oppression as women is, after all, without a doubt, the longest revolution.

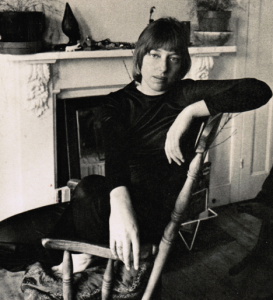

Photograph by Jerry Bauer of Juliet Mitchell on the cover of Women’s Estate (1971).

SS: A central claim of WLR, that the call for complete equality between the sexes remains completely within the framework of capital rather than in opposition to it, implies that the relationship between men and women, like the class distinction between capitalist and worker, itself derives from the contradictions of capitalism. The conditions that allow for and motivate the reproduction of “patriarchy” as well as other kinds of oppression, in other words, also form the essential conditions of possibility for the demands for equality. You presciently noted in WLR, applying the thesis of repressive desublimation, that the wave of sexual liberalization unleashed in the 1960s could lead to more freedom for women, but “equally it could presage new forms of oppression.” Does our historical remove from the 1960s allow us to judge one way or another?

JM: I think, first of all, that in the 1960s I thought or felt that a measure of equality might be attained within the dominant socioeconomic class. I am now unsure that it will even be attained there. So it may be the ideology of capitalism has been hoisted on its own petard; in other words, caught and stuck within its own contradictions. The bourgeois husband needs a bourgeois wife. What we hadn’t foreseen sufficiently was the return of the servant class if this wife was also to work. We were not surprised that there is no pay parity, nor had we failed to realize that, although there are some women who will climb the ladder, this is not going to affect the wretched of the earth, or where it does so it may do so negatively. Women can now vote, but now there are certain, increasingly disproportionate, sectors such as illegal migrants, who don’t enjoy the equalities that those in liberal capitalist societies should. More importantly, can we really call the old democracies democratic when it is money not the vote that rules? Any struggle is always one step up the well and two steps down, or the two steps up and one step down, its never simply a matter of progress under capitalism, nor is it a matter of this ghastly government over another. There are liberal aspects of capitalism and for heaven’s sake let’s have them. All the egalitarian bits of capitalism must be pressed for if only to find out two things: one, that going the whole way towards equality is impossible under capitalism, and two, that going beyond these forms of equality is essential anyway.

I also think it is important that I wasn’t prescient about the massive entry of women into the workforce, I wasn’t prescient in WLR in seeing that education was going to expand as much as it did, and I think that I wasn’t prescient about changes in production (I later addressed these issues elsewhere) or reproduction. Shulamith Firestone foresaw the “reproduction revolution” in some ways, but then again she was writing in the 1970s, not the mid-sixties; there was a women’s movement by the time she wrote. With sexuality things are a little more complicated. I think there are always social classes, there are therefore different effects for the wretched of the earth than there are for the rich, so the degree to which I was prescient I don’t know whether the measure of sexual liberation that effective contraception offered us middle-class “first-worlders” has created more oppression of women sexually worldwide—I don’t think so. What I think it has done is definitely exposed the differences more.

SS: WLR raises the issue of revolutionary strategy: the role of limited ameliorative reforms versus proposing maximalist demands. It treats as salutary the remark Lenin made to Clara Zetkin about developing a strategy commensurate with a socio-theoretical analysis of capitalism within the party to adequately address the “women’s question.” More recently, at a talk at Birkbeck in 1999, you ventured to wonder aloud, albeit with an understandable sense of nervousness, whether, in an era otherwise marked by acute depoliticiziation, the uptick of interest in psychoanalysis, sexuality, and the “women’s question” might mean that Lenin was possibly right that such concerns are the noxious fruits growing out of the soiled earth of capitalist society. Has the naturalization of feminism in the present-day obscured the issue of strategy?

JM: I do still believe in crude old things like “to each according to his needs.” People do need different things and that is beyond equality in a sense. This is where history comes in. Society is still trying to think that we all ought to be equal, but we haven’t yet the kind of society that adequately attends to our needs.

The extreme of reformism versus voluntarism is not where we are at the moment. I think these are the concerns that come out of “the soiled earth of capitalist society,” but again my answer would be rather like my answer about equality, that this doesn’t invalidate these concerns. These are perfectly legitimate demands that are not confined by the conditions in which they come into existence. For example, if one looks at what happened to sexuality or reproduction in the Soviet Union, it would have been much better to follow the earlier tide in which sexual freedoms were seen as a condition of the revolution. That is, when Alexandra Kollontai wrote on free sexuality, that wasn’t only a bourgeois demand, nor was it in 1968. A revolutionary situation is a discreet situation that transforms what could be thought within capitalism about sexuality, but it is not identical with capitalism; revolutions create the possibility of change, revolutions change the object. Though we are not in a revolutionary situation, that doesn’t mean it is not around the corner.

The Old Left thought of capitalism as en route to communism. On the withering away of the state, there was a voluntarist injunction to abolish the family and then the opposite, producing a very interesting contradiction that cannot be chalked up to the fact that Stalin was a foul man. It may be that you can’t wither away the family, or can’t wither away the state, but the question is why? If, as Marx himself says, the call by utopian socialists to abolish the family would be tantamount to generalizing the prostitution of women, then what is the solution or next stage? This is why WLR examines the structures within the family. Marx was against the voluntarism of the abolition of the family. But then what measures escape reformism? There may be changes to the things that a family does that will lead to its diversification in such a way that is more revolutionary than what existed thus far under socialism or capitalism. Maybe there is something there to be thought about as new demands that are beyond socialism as well as beyond capitalism.

Tea break

SS: The program from the memorial service for Fred Halliday on the bookshelf reminds me of an anecdote that is recounted in an interview with Danny Postel.[5] He dreamt of appearing with Tariq Ali before Allah who says that one will veer to the Right, the other to the Left, without specifying who would head in which direction. I think we in Platypus often return to that story as a salient metaphor for the fragmentation of the New Left and the opacity of the present-day. He was planning to do a couple of events with Platypus on an upcoming visit to the US that were alas never realized.

JM:His death is indeed tragic, but I like this story about Tariq and Fred; I think it is important to take up arguments with those who share the same space politically, if only to disagree. I disagree with feminists who dismiss Freud; both of us probably think we are going towards the Left, but we might both be going Right.

SS:For me, getting back on track, I should confess there is an intractable dilemma at the heart of WLR. On the onehand, there are passages gesturing toward a dialectical conception of capitalism—as bothrepressive as well as potentially emancipatory—while, on the other hand, the Althusserian notion of “overdetermination” that structures the argument emphasizes the role of contingency as the motor of historical change. As Althusser himself acknowledged, the idea of “overdetermination” was indebted to the anti-humanistic reinterpretation of Freud by Lacan. Can one accommodate the denial of the subject as an illusion of the ego in the Lacanian “return” to Freud with the Freudian emphasis on psychoanalysis as an ego-psychology therapy intended to strengthen the self-awareness and freedom of the individual subject as an ego?

JM: No, I never had any time for ego-psychology, but that isn’t the same as the question about overdetermination. Some of the observations of Anna Freud are remarkable, but I don’t see the whole concept of strengthening the ego as a way forward for psychoanalysis, although I suppose there is a context in which it could help if someone were completely fragmented; then there are stages, but it should only be a stage on the way to something else. For me it wasn’t a shift from Lacan to Freud as such. I had met R. D. Laing in 1961. The Divided Self had came out shortly before, in 1959, so I was involved with anti-psychiatry in the same span of time as I was involved with the New Left Review.

On overdetermination as Althusser takes it from Freud: Overdetermination in Freud is not an anti-humanist concept, in Lacan maybe it is, but in Freud it is neither/nor. What it means is that there will always be one factor that is the key factor. And in Freud that is not socioeconomic. What I liked about Althusser was the definition of ideology as at times overdetermining. Ideology, in the Althusserian sense, interpellates individuals as subjects. Now, what Althusser offered me intellectually, so to speak, was that revolutionary change in any one of the superstructural or ideological state apparatuses can attain a certain autonomy, can occur even when it doesn’t elsewhere. Yet, in the last instance, the economy is determinate.

SS: This raises a number of issues about the relationship of Althusser to Marx and that of Lacan to Freud. Does theAlthusserian concept of ideology adequately address the ways in which we are forced to deal with our own alienated freedom in capital through reified forms of appearance and consciousness? Did the limitations of the Althusserian-Lacanian framework in WLR motivate the reconsideration of Freud?

JM: You might change sexuality or reproduction or sexualization, but if production remains unchanged, these will remain changes within those specific fields. This claim struck me as valid for the situation of women. I could use this insight to organize the structures that apply to women, which was the family. I broke down the family, each aspect of which I treated as superstructural, but that was in the final analysis determined by production, which was outside it. There I was puzzling over the fact that women are marginal but that, as in the Chinese revolutionary saying, “women hold up half the sky.” How does one think that? The only way I could think it was to break it up into these structures: production, reproduction, sexuality, and the socialization of children. Apart from what I quote—Engels, Bebel, Lenin, Simone De Beauvoir, and Betty Friedan—there was no category “woman” until feminism resuscitated it in the second half of the sixties.

Now, retrospectively, I would say that the intransigence of the oppression of women, as Engels had identified, also entails that it is the longest revolution. In turn the idea of the longest revolution as I wrote WLR made me think about what was absent in earlier analyses but also within Marxist thought. How do we view ourselves in the world? This is what took me to Freud; it took me first to the unconscious rather than sexuality. I thought, at least I thought then, that the unconscious was close to what Althusser had to say about ideology. The return to Freud was “overdetermined”—there were multiple directions for my getting to Freud.

SS: Given your own trajectory, what do you make of the reflorescence of a strain of Althusserian-Lacanian “Marxism” today in the form of Balibar, Rancière, and Badiou?

JM: I suppose this is getting me back to when I wrote WLR. I found Althusser extremely useful, but there was always a humanist in me. I think that remains true, despite all the shake-ups of postmodernity or whatever. I always wanted both perspectives, it was never a matter of either/or. I think we need to rethink our humanity in order to revalidate the universal—neo-universalism—which was interestingly debunked by postmodernism.

SS: Does the contemporary emphasis on performativity or gendering obscure the humanist motivations that led radical anti-feminists to psychoanalysis?

JM: It certainly changes it, it redirects it in a different direction, or it might be, as Judith Butler always tells me, that I haven’t understood performativity properly. I think where I was going with psychoanalysis was more towards kinship, towards what is still fundamental in kinship structures in families, what effects does it have in creating sexual difference. When we talk about interpellation from Althusser, the primary one is “it’s a girl” or “it’s a boy.” I am still trying to work this out in a way, which relates to my work on siblings. Everybody seems to be muddling up gender and sexual difference to me. And it stretches back to the old confusion between sexuality and reproduction. Gender, which can be looked at psychoanalytically, is an earlier formation than sexual difference and fantasies of reproduction are parthenogenic—imaginatively boys and girls equally give birth. Sexual difference takes up heterosexual reproduction. Gender can be made into a category of analysis whereas women can be the object but cannot be a category, which is why one can ask such questions as: Why is hysteria gendered? Why is mathematics gendered? Why is everything gendered?

SS: There was a classic Marxist prejudice against Freudian psychoanalysis. Lukács, as one example, considered Freud an “irrationalist”—as a “symptom.” For Marxist radicals, Freud characterized the limits of “individual” subjectivity with which the revolutionaries had to contend in order to make their revolution. Wilhelm Reich was one of the first Marxists to critically appropriate Freudian categories to describe the social-historical condition of life under capital by perceptively identifying our fear of freedom. Do you think that the shift toward psychoanalysis by radical Marxists from the 1930s on, through the feminist embrace of psychoanalysis to address a felt deficit in the 1960s, registers the internalization of the defeat or is somehow apolitical?

JM: From where Lukács stood, feminism and psychoanalysis looked terribly pessimistic. I think it is the longest revolution. One needs, as Gramsci says, the conjuncture of the optimism of the will and pessimism of the intellect to realize the difficulties. These difficulties can be taken to psychoanalysis usefully, but from where Lukács was standing you couldn’t. He was asking a different question of a different object. When I took up Laing, Reich, and the feminists in Psychoanalysis and Feminism, I never believed one could use psychoanalysis to be on the Left, rather it was what can one use psychoanalysis for to answer the question about the oppression of women, which is an abiding question for the Left.

What I am saying is that psychoanalysis would be different in a revolutionary context than in the fascist context in Berlin in which Reich wrote. I am critical of Reich, but there was an important liberal aspect within psychoanalysis, so that all of the work that Marxists within psychoanalysis were able to do in the polyclinics of Berlin before they were stamped out or forced into emigration by the Nazis, was radical, precipitating a revolution within psychoanalysis as well as within Marxism. Bourgeois concepts start to take on radical implications in the context of a revolution, as with the Marxists of the Second International in the 1920s. The context of the Bolshevik Revolution changed the significance of what Bebel had written on women for Lenin.

SS: The New Left icon Herbert Marcuse sought to outline what a socialist society would look like in Eros and Civilization. The alienation of labor in capital, Marcuse argues, means that the satisfaction from work can only ever be an ersatz form of libidinal release. In a nonrepressive socialist order, on the other hand, work would be recathected, and transformed into play. He also asserts that Freud had hypostatized the existence of the death drive, when in fact it is applicable only to the aggression that attends capitalist society. “WLR” concludes with a critique of such attempts to prefiguratively sketch out what an emancipated society might look like, posing starkly the danger of trying to measure the concrete character of an emancipated future. What are the challenges that confront the Left of the future in preserving the indeterminacy of the concept of socialism?

JM: On the first half of the question about the absence of play and the relationship of the death drive to capitalism: the death drive is a huge question, but why it should be limited to capitalism, not to slave or feudal society is beyond me. Maybe there will be a beyond, but maybe there will simply be ways in which we can work with the death drive or diffuse the id, since it isn’t only violence, it is the return to stasis. It is a hypothesis. I don’t agree with Marcuse; today there are new forms which it takes.

Why aren’t we even where we were in the 60s anymore? I already told you we hit a ceiling, but there are new spaces opening up for the Left. Class will feature in the whole dilemma of illegal migrants, as in Mike Davis’s Planet of Slums. The Left needs to start to think from Planet of Slums, which is a different location from that of the industrial working class of Marx or even the consumer capitalist class of late capitalism of Althusser or of Marcuse. Planet of Slums forecasts a different world, but there will always be a women’s question, as there will be a race question, or a class question.

SS: Apart from the French tradition, the Frankfurt School, especially the work of Adorno, represents another important attempt to appropriate descriptive Freudian categories into a critical Marxist theory. Against Marcuse, Adorno held that it was a necessary symptom of capitalist society, which was characterized by a growing narcissism that weakened the defenses of the ego against the super-ego, that both psychological (ego psychology) and sociological (Parsonian sociology) approaches to social totality had to remain aporetic. The function of the ego, in other words, does not remain unscathed by the irrational reality of capitalist society with its endless means-ends reversals. What role do you think psychoanalysis can play in helping us cope with the normative psychosis of our sociopolitical world? Or, putting it in a more open-ended manner, what kind of emancipatory possibility might there be in the narcissistic character—what Adorno referred to as authoritarianism—of subjects of late capitalism?

JM: Quite correctly Reich had asked the question of the authoritarian personality that was then taken up by the Frankfurt School. I still think their work on the authoritarian personality is a marvelous use of psychoanalysis. Their use of psychoanalysis allowed them to ask questions about the role the authoritarian personality would play in collusion with or in the self-replication of fascism. The Frankfurt School took to psychoanalysis. Lukács thought you couldn’t, approaching it differently from within communism or within socialism trying to call itself communism. I never wanted to psychoanalyze society. I am uninterested in saying that society is narcissistic, depressive, or anything like that, but we are all still of the Left. Hopefully, Allah would say we will all go to the Left, even though we use psychoanalysis for different objects. Freud himself was saying we can change society, in discussions about “Why War?” with Einstein, what can we do to stop war. He then relied on theories of psychoanalysis to try to find some sort of answer—interestingly it turned out to be about the role of aesthetics. He thought from within the clinic as well as from elsewhere. I don’t know what Adorno says in full, but just as a quick last note, in pursuing emancipation in the heart of darkness we also need to let light into the heart of darkness. |P

Transcribed by Atiya Khan

[1]. Juliet Mitchell, “Women: The Longest Revolution,” New Left Review, I/40 (November-December 1966): 11-37.

[2]. C. Wright Mills, “Letter to the New Left,” New Left Review, I/5 (September-October 1960): 18-23.

[3]. Juliet Mitchell, Women’s Estate (New York: Pantheon Books, 1971), 58.

[4]. Ibid., 71.

[5]. “Who is Responsible?: An interview with Fred Halliday,” interview by Danny Postel, Salmagundi, 151-152 (Spring-Summer 2006), http://cms.skidmore.edu/salmagundi/backissues/150-151/halliday.cfm.