Lessons from the election

Eric Stoner

Platypus Review 30 | December 2010

IN A STRANGE WAY, the debate over whether the American left should support the Green Movement in Iran resembles the arguments that took place in progressive circles before the 2008 presidential elections in the United States, and that reemerged in the recent midterm elections. Those in the Obama camp either believed him to be their savior, taking his every word as gospel, or, if they had a more sober political outlook, simply resorted to some version of the tired “lesser of two evils” argument. If elected, this crowd contended, Obama would at least be more open to the progressive perspective than McCain, which was reason enough to vote for him. It was argued that the threat posed by a Republican victory was so great that the various factions on the Left needed to put aside their differences until after Obama was elected. At that point, he would reveal his true progressive self, and if that did not happen, at least there would be a more reasonable partner to negotiate with in the White House, who could be pressured to move to the Left. Meanwhile, anyone who decided to critique Obama from the Left by saying that his proposed policies—which left much to be desired, to put it mildly—should have had a greater bearing on one’s behavior in the voting booth than his elocution, were seen by Obama’s supporters as traitors or idealists totally out of touch with political reality.

In the end, many on the Left begrudgingly cast their ballots for Obama even though he consistently moved to the right during the campaign—backing the massive, hugely unpopular bailout of Wall Street, withdrawing his support for a single-payer universal health care system, and calling for a larger military, with more troops in Afghanistan and more Predator drone attacks in Pakistan. The results of this compromise are now evident. Since Obama was elected he has, not surprisingly, continued down the treacherous path he campaigned on and the sense of hope and change that was ever-present during his ascent is now difficult to find. Indeed, as seen during the midterm elections last month, most leftists fell into a pattern of recrimination and resignation similar to the lead-up to the presidential election, only this time a widespread melancholy had replaced the euphoric hope of 2008.

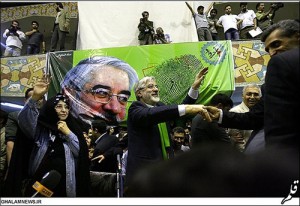

Mir-Hossein Mousavi at a Green Movement rally in Iran, 2009.

The differences between the candidates in Iran’s presidential election last year were far starker than the differences Americans faced when voting for Obama or McCain in 2008. President Ahmadinejad is a world-class demagogue and his government has been extremely repressive, committing widespread human rights abuses and imprisoning, torturing, and killing those who voice dissent. Mir Hossein Mousavi, on the other hand, has generally advocated for greater political and social freedoms for all Iranians. Given this contrast, many argued that the Green Movement should be uncritically supported because, if nothing else, getting Mousavi in power would at least give the Iranian left some “breathing room” to organize. In turn, little tolerance has been shown by many supporters of the Green Movement for those who chose to point out the faults of Mousavi or the other presidential contenders. When it comes to economic policy, the difference between Ahmadinejad and Mousavi is particularly opaque. Though 60 to 70 percent of the Iranian economy is still nationalized, there is little evidence to support the position, argued by some on the American left, that Ahmadinejad is a bulwark against the destructive forces of neoliberalism. On the contrary, as critics have documented in extensive detail, since assuming the presidency in 2005 Ahmadinejad has crushed organized labor, enthusiastically privatized state assets, and courted foreign investment.

The leaders of the Green Movement, to the extent that there are leaders, have said remarkably little—apart from supporting the right of labor to organize, which would be an important victory—about what they would do differently. In fact, the little that is known about their positions would seem to indicate that, if not true believers, they are at least open to the ideology of neoliberalism. While supporters of Mousavi have pointed favorably to his record on economic issues during his tenure as prime minister in the 1980s, his most influential financial backer during his run for president last year was Hashemi Rafsanjani, the billionaire cleric and former president of Iran, who is an outspoken advocate of “free market” reforms. Medhi Karroubi, another presidential candidate who is now a leading figure in the Green Movement, embraced neoliberalism even more openly during the campaign. According to Iranian political analyst Rostam Pourzal, the centerpiece of his economic platform “consisted of suggested first steps towards de-nationalization of Iran’s oil industry. The scheme was devised by the candidate’s chief economic advisor, a self-described Milton Friedman devotee named Masoud Nili.”[1]

Despite these ominous signs, many supporters of the Green Movement held that pushing Mousavi to clarify his economic ideas would only further split the Iranian left, so that any concerns with his political shortcomings should be dealt with only when the democratic movement prevails. However, ignoring where Mousavi and Karroubi fall short in the name of unity, and failing to push them to emphatically reject neoliberalism, reveal misguided and dangerous politics. Indeed, the most advantageous time for everyday citizens to get politicians to address their concerns is while they are running for office or leading a movement for political reform, as this is when politicians are most vulnerable and in need of broad support. Once they have gained power—especially if they’ve done so without addressing the demands of a particular sector of society—there is little incentive for them to change course.

There is no better time for Iran’s working class to make its voice heard than now. Mousavi and the Green Movement are in desperate need of a boost. At the end of last April, Mousavi released a video statement urging workers and teachers to join the cause, but any attempts to recapture the momentum of the summer of 2009 have proven unsuccessful. Along with this, leftists internationally have by and large lost interest, with reports of developments in the Green Movement becoming fewer and farther between. For precisely this reason, the Iranian labor movement is poised to pressure Mousavi by making their support for him contingent on his publicly rejecting neoliberalism and seriously addressing the demands of the working class. If he refuses, Iranians should begin promoting new leaders that more fully embrace their goals, or better yet, start creating alternative economic institutions themselves.

In recent decades, many nonviolent movements that have successfully brought down repressive governments or overturned fraudulent elections have made the mistake of not paying due attention to economics, and paid a heavy price. When Solidarity came to power in Poland in 1988, for example, its leaders abandoned the progressive economic program that they had promoted since the beginning of their struggle, which included converting state-run industries into worker cooperatives, and adopted a toxic mix of neoliberal economic reforms. These included eliminating price controls, slashing subsidies, and selling off state-owned mines, shipyards and factories to the private sector. As a result, the country’s economy took a nosedive: industrial production plummeted, unemployment soared, and the percentage of the population living in poverty rose dramatically. Hence, Solidarity’s victory was only partial. Polish workers gained political freedoms, but only by constraining their economic freedom in many ways.

If the Green Movement hopes to avoid irrelevance, on the one hand, and a problematic “victory” won only through a Faustian bargain, on the other, those involved must make the interests of working people much more central to their struggle by explicitly raising the banner of economic justice. The ultimate defeat of the Green Movement in the elections deepens, rather than diminishes, the significance of this lesson. Otherwise, Iranians may establish a government that is more democratic on the surface, only to be quickly disappointed to find their lives constrained anew by corporations, which are profoundly undemocratic institutions. To take but one example, freedom of speech, and especially a free press, cannot truly exist when a handful of corporate giants with an interest in maintaining the status quo control of virtually everything read, heard, or seen in the media. As those involved in the Green Movement continue their struggle for political and social freedoms, they should not downplay the importance of having democratic control of the workplace.

To ignore questions of economic policy is not a wise strategic move for the opposition in Iran, but is evidence of a lack of understanding regarding the true threat that neoliberalism poses to real democracy. Now is the time, both in the U.S. and Iran, for leftists to draw a line in the sand, to stop making concessions at every turn in the interest of “pragmatism,” and to struggle for the society they truly want to live in—not some uninspiring, deeply compromised alternative. |P

[1] Rostam Pourzal, “Iran’s Business Elite, Too, Is a ‘Dissident,’” MRZine, June 27, 2009 <http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/2009/pourzal270609.html>.