1968

The Decline of the Left in the 20th Century

Toward a Theory of Historical Regression

Platypus Review 17 | November 2009

On April 18, 2009, the Platypus Affiliated Society conducted the following panel discussion at the Left Forum Conference at Pace University in New York City. The panel was organized around four significant moments in the progressive separation of theory and practice over the course of the 20th century: 2001 (Spencer A. Leonard), 1968 (Atiya Khan), 1933 (Richard Rubin), and 1917 (Chris Cutrone). The following is an edited transcript of the introduction to the panel by Benjamin Blumberg, the panelists’ prepared statements, and the Q&A session that followed. The Platypus Review encourages interested readers to view the complete video recording of the event, available at the link above.

1968

Atiya Khan

Theory becomes a material force when it has gripped the masses.

— Karl Marx, A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right [1843]

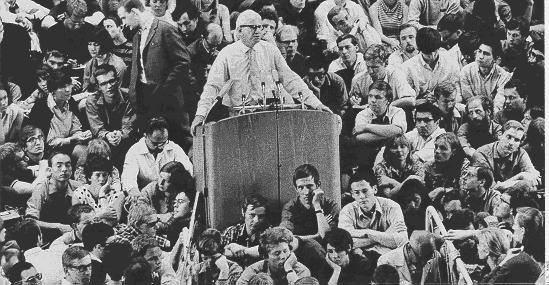

Herbert Marcuse speaks to students.

IT MIGHT SEEM COUNTER-INTUITIVE to approach the date of 1968 through the political thought and self-understanding of Theodor Adorno, who is not only considered the most pessimistic in his critique, but also deemed an opponent of the New Left, especially after he infamously called the police on student demonstrators at the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research. Yet Adorno’s response to the politics of 1968 can help us understand both the roots of New Left politics and its legacy today. In his late writings, such as “Late Capitalism or Industrial Society?” (aka “Is Marx Obsolete?”), “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis,” and “Resignation,” as well as his private correspondence with Herbert Marcuse on the character of the student movement in the 1960s, Adorno formulates important categories for a Marxian attempt to grasp the problem of theory and practice. He reminds us, “theory becomes a transformative force” only through “a reasoned analysis of the situation. In reflecting upon the situation, analysis emphasizes the aspects that might be able to lead beyond the given constraints of the situation.”[1] Hence, following Marx, Adorno emphasizes that the crucial lesson to be learned from the history of Marxism is that the mediation between theory and practice can only be grasped in the dynamic of revolutionary emancipatory politics. On the basis of Adorno’s writings, one can address the problem of “regressive” consciousness that beset the student movement of 1968, one of the critical moments in the history of the Left.

The Left since Marx’s day has wrestled with the problem of theory and praxis, but never so much as since 1968, the culminating moment of the post-World War II New Left. In his critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Marx elucidated the conditions in which an effective relation between theory and practice in the attempt to change the world becomes possible. Such conditions of advancing the relation between theory and practice, as Marx reflected upon around the moment of the revolutions of 1848, arose in the history of modern society with the emergence of the proletariat—the modern working class of wage labor—and the historically specific constitution of industrial labor.

The historically specific, dialectical dynamic of capital is what both gives rise to and constrains the possibility of a post-capitalist, emancipated form of life. Armed with this insight, Marx examined the forms of discontent with capital emerging in the 19th century, which took the form of class struggles of the workers against capitalists, as immanent to the constitutive and contradictory character of social exploitation and domination under capitalism. Thus, in Marx’s conception, for the masses to be gripped by theory, for a progressive advance in their consciousness, theory must become a means of revolution

Like the October Revolution of 1917, the eruption of student protests in 1968 emerged as an international phenomenon extending from Frankfurt, Berlin, Paris, Rome, and Prague to San Francisco as well as to the major cities of Latin America and South and East Asia. The process of politicization that proceeded at a furious pace involved an increasingly militant protest against “authoritarian structures” and traditional values of society. What united the students was their demand for educational reforms, opposition to the war in Vietnam, loathing of the inhumanity of capitalism, and solidarity with liberation movements of the Third World.

Yet what set this moment apart from the preceding revolutionary uprisings was an uncritical emphasis on “action” as well as a deep-seated aversion to theoretical reflection and analysis. This attitude found expression in the disruptive modes of behavior of the students, which involved interrupting lectures and discussions, occupying buildings, and going so far as to dismiss intellectuals by using the word “professor”—“to put them down, as they put it so nicely, just as the Nazis used the word ‘Jew,’” Adorno remarked in his letters to Marcuse.[2] Slogans such as “We can’t get bogged down in analysis” or “Whoever occupies himself with theory, without acting practically, is a traitor to socialism,” also affirmed that the student movement on the whole was symptomatic of a particular tendency that was, as Adorno observed, “regressive,” fascist in potential, and “authoritarian” in its attitude.

Jürgen Habermas

Taking into consideration such developments, Adorno used the epithet of “left-wing fascism,” originally coined by Jürgen Habermas, to warn of the dangers of a student movement that could just as easily converge with fascism. This characterization of the New Left, which became a point of contention between Adorno and Marcuse in their private letters, brought to the fore not only their differing views on the politics of the moment, but also offers us insights into the way in which the New Left of the 1960s was a legacy of the unfulfilled potential of the Old Left of the 1930s. Adorno’s main point was that the Left had not learned from its past defeats.

In his letters to Marcuse, who had embraced the student movement unreservedly, Adorno frankly expressed his doubts about the political consequences of practical action. He wrote that many of the student representatives tended “to synthesize their practice with a non-existent theory and this expresses a decisionism that evokes horrific memories.”[3] This was a gesture to the emergence of counter-revolution—expressed in the form of fascism/Stalinism—that had ensued in the aftermath of the crisis of 1917 leading to the disintegration of revolutionary Marxism by the 1930s and generating an acute problem of consciousness on the Left. In the postwar period, the devastation of the Left was supplanted by an “authoritarian character structure” that was expressed universally, not only in the fascist rallies, but also in the Popular Front movements, as well as in the anti-colonial, nationalist movements of the Third World. Frankfurt School theorists, including Adorno, theorized the notion of the “authoritarian personality” as a double-sided expression of counter-revolutionary and simultaneously, revolutionary potential that was rooted in the dialectical contradiction of capitalism. Borrowing from Freudian psychoanalysis, Adorno and his colleagues (Marcuse and Reich) interpreted the constitution of the “authoritarian personality,” characterized by “narcissism” and sadomasochism, as evincing a regressive “fear of freedom.” Thus, faced with “political hysteria” Adorno observed, “Those who protest most vehemently are similar to authoritarian personalities in their aversion to introspection.”[4]

Certainly the 1960s marked a political crisis, but one in which the Left, instead of evaluating the legacy of the 1930s Stalinism, reproduced those very structures and tendencies it sought to overthrow. As Adorno asked of Marcuse, How could one only protest against the horror of napalm bombs, and not revolt against the “Chinese-style tortures” that the Vietcong practiced with such unrestraint? He continued, “If you do not take that on board too, then the protest against America takes on an ideological character.”[5] In the course of this correspondence, Marcuse acknowledged that the situation “was not a revolutionary one, not even a pre-revolutionary one,” but the situation was “so terrible, so suffocating, so demeaning, that rebellion against it forces a biological, physiological reaction; one can bear it no longer, one has to let some air in. And this fresh air is not that of a ‘left-wing fascism.’”[6] Marcuse insisted that the situation had changed qualitatively, that it did not resemble the 1930s in any way, but called “more urgently today than ever for a concrete political position,” especially against American imperialism. It may be worthwhile to note that Adorno did not simply oppose Marcuse’s assessment of the 1960s New Left, but wished to avoid the pitfalls of either Stalinophobia, the anti-Leninist anarchist tendency espoused by Horkheimer, or Stalinophilia, the militant New Left tendency à la Maoism and Castroism, exemplified by Marcuse’s political stance. In his essay “Resignation,” Adorno emphasizes that even though the return of anarchism is that of a “ghost,” that is, of unresolved problems of Marxism, “this does not invalidate the critique of anarchism.”[7] In his attempt to transcend both Stalinophobia and Stalinophilia, Adorno stressed the necessity of critiquing the contemporary form of Marxism and its problematic relation to its past.

Return to Normal. Poster from May 1968 Paris

Adorno’s great insight was that he rooted the problem of authoritarianism in the structure of modern capitalist society. In his essay “Late Capitalism or Industrial Society,” he used Marxian categories to analyze the basic structure of contemporary society, which he explained was contradictory based on the dynamic of labor and capital. The drive to produce surplus value and capitalize on labor measured in socially necessary labor time was the source of social domination and exploitation. Exploitation in the traditional sense of class antagonism could no longer be established empirically because the working class had been subject to a high degree of social integration in the mid-20th century. Adorno characterized capitalism as a society driven by increasing levels of productivity, resulting in great increases in use-value output. He summed up this organization of social life as “the administered world”—a tendency that was expressed in both state-regulated capitalism and the welfare state system. However, the dynamism of growth displayed certain static tendencies reflected in the dominance of the relations of production, which included relations ranging from those of the administration of managerial bureaucracy to those of the state and the organization of society as a whole. “This creates the impression that the universal interest is to preserve the status quo and that the only ideal is full employment and not liberation from heteronomous labor.”[8]

The “administered world” produced a specific kind of mass society, what Adorno called the “culture industry.” The culture industry was largely the consequence of high levels of productivity and the widespread availability of consumption goods, but it was also illusory in that it gave the appearance of mass democratization when in fact production was standardized and tastes were manipulated only to preserve a pretense of individuality. This implied “the impotence of the individual in the face of totality [that] is the drastic expression of the power of exchange relations.”[9] Thus Adorno declared, “Marx’s dictum that theory becomes a real force when it grips the masses was flagrantly overturned by the course of events.”[10] The culture industry eventually paralyzed “the ability to imagine in concrete terms that the world might be different,” because the authoritarian character structure had itself become the force of repression.[11] Towards the end of his essay, borrowing from Freud, Adorno pointed to the “free floating anxiety” that arose from the “subjective regression [that] favors the regression of the system.” The consciousness of the masses had become seemingly identical with the system, which in turn had become increasingly alienated.[12]

Adorno was not opposed to people organizing themselves for political purposes, but he wished to draw attention to the “Archimedean point” at which “a non-repressive practice might be possible, and one might steer a path between the alternatives of spontaneity and organization.” This point, if it existed at all, “can only be found through theory,” Adorno maintained.[13] His own position arose from a political judgment that was based on a sober analysis of the situation. He made this clear in his controversy with Marcuse. “You [Marcuse] believe that practice in an emphatic sense is not blocked today; I see the matter differently.”[14] Given this scenario, Adorno was convinced that the student movement was bound to fail from the outset. In “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis,” he noted that the building of the barricades is “ridiculous against those who administer the bomb.”[15] A practice that refuses to acknowledge its own weakness when confronted by “real power which hardly feels a tickle” is deluded and regressive, or, at best, “pseudo-activity.”[16]

Adorno’s critique of the New Left was an honest attempt to shake the Left out of its state of self-abnegation and self-delusion. The problematic inheritance of the legacy of the 1930s meant that the intent of Marxian theory and practice had become an obscure issue by the 1960s, and the problem of social consciousness reemerged in the guise of “ego-weakness” that “refuses to reflect upon its own impotence.”[17] The political “radicalization” of the 1960s only meant further regression and, therefore, subjectively obscured the possibility of progressive transformation beyond capital even when objectively it was still possible. The deep irony of this history is that there has been no progress at all since 1917, and in fact the crisis of Marxism and that of social consciousness has been deepened, not solved. At a fundamental level the problem of consciousness is tied to what Wilhelm Reich had identified as the “fear of freedom” necessitated by a conservative psyche that is wedded to its symptomology. So the symptom needs to be worked through, as this not only provides an occasion for self-understanding and knowledge, but also constitutes the subjective, psychological preconditions of freedom. |P

Next presentation: 1933

[1]. Theodor W. Adorno, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis,” in Critical Models: Interventions and Catchwords (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 264.

[2]. Theodor W. Adorno to Herbert Marcuse, Frankfurt, June 19, 1969, in “Correspondence on the German Movement,” New Left Review I/233 (January–February 1999): 132.

[3]. Stefan Müller-Doohm, Adorno: A Biography, translated by Rodney Livingstone (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2005), 456.

[4]. Adorno, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis,” 271.

[5]. Adorno, “Correspondence on the German Movement,” 127.

[6]. Ibid.,125.

[7]. Theodor W. Adorno, “Resignation,” in Critical Models, 292.

[8]. Theodor W. Adorno, “Late Capitalism or Industrial Society?” in Can One Live After Auschwitz?: A Philosophical Reader, edited by Rolf Tiedemann and translated by Rodney Livingstone (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press), 119.

[9]. Ibid., 120.

[10]. Ibid.

[11]. Müller-Doohm, Adorno, 446.

[12]. Adorno, “Late Capitalism or Industrial Society?,” 124.

[13]. Müller-Doohm, Adorno, 462.

[14]. Adorno, “Correspondence on the German Movement,” 131.

[15]. Adorno, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis,” 269.

[16]. Ibid., 271.

[17]. Ibid., 273.