The fourth installment of a panel series, held at the University of Chicago on November 23rd, 2013. The first three panels were held in Halifax, Frankfurt, and Thessaloniki.

A moderated panel discussion and audience Q&A with thinkers, activists and political figures focused on contemporary problems faced by the Left in its struggles to construct a politics that adequately address issues of democracy. Hosted by the Platypus Affiliated Society at the University of Chicago.

Panelists:

MICHAEL GOLDFIELD (Wayne State University)

AUGUST NIMTZ (University of Minnesota)

PETER STAUDENMAIER (Marquette University)

From the financial crisis and the bank bail-outs to the question of "sovereign debt"; from the Arab Spring to Occupy Wall Street; from the struggle for a unified European-wide policy to the elections in Greece and Egypt that seem to have threatened so much and promised so little—the need to go beyond mere "protest" has asserted itself: political revolution is in the air, again.

At the same time, the elections in US and recently in Germany, by comparison, to be a non-event, despite potentially having far-reaching consequences for teeming issues world-wide. Today, the people—the demos—seem resigned to their political powerlessness, even as they rage against the corruption of politics. Hence, while contemporary demands for democracy to politicize the demos, they are also indicative of social and political regression that asks urgently for recognition and reflection. Demands for democracy "from below" end up being expressed "from above": The 99%, in its already obscure and unorganized character, didn't express itself as such in the various recent elections, but was split in various tendencies, many of them very reactionary.

Democracy retains an enigmatic character, since it always slips any fixed form and content, since people under the dynamic of capital keep demanding at time "more" democracy and "real" democracy. But democracy can be like Janus: it often expresses both the progressive social and emancipatory demands, but also their defeat, their hijacking by an elected "Bonaparte."

What is the history informing the demands for greater democracy today, and how does the Left adequately promote—or not—the cause of popular empowerment? What are the potential futures for "democratic" revolution, especially as understood by the Left?

Questions:

1. What would you consider as "real" democracy, as this has been a primary demand of recent spontaneous forms of discontent (e.g. Arab Spring, Occupy, anti-austerity protests, student strikes)?

2. What is the relationship between democracy and the working class today? Do you consider historical struggles for democracy by workers as the medium by which they got "assimilated" to the system, or the only path to emancipation that they couldn't avoid trying to take?

3. Do you consider it as necessary to eschew establishment forms of mass politics in favor of new forms in order to build a democratic movement? Or are current mass form of politics adequate for a democratic society?

4. Why has democracy emerged as the primary demand of spontaneous forms of discontent? Do you also consider it necessary, or adequate, to deal with the pathologies of our era?

5. Engels wrote that "A revolution is certainly the most authoritarian things there is." Do you agree? Can this conception be compatible with the struggle for democracy?

6. How is democracy related with the issue of possibly overcoming capital?

7. Is there a difference between the ancient and the modern notion of democracy and, if so, what is the source of that difference? Does "real" democracy share more with the direct democracy of ancient polis?

8. Is democracy oppressive, or can it be such? How do you judge Lenin's formulation that: "democracy is also a state and that, consequently, democracy will also disappear with the state disappears."

October 15, 2013, 7 PM

Conference Room, Reynolds Club, University of Chicago

Join us for a teach-in on the history of capitalism, its problematics and possibilities, from the perspective of the present. Our speaker will lecture for about half an hour; this lecture will be followed by questions and discussion for another half hour.

The project advanced by the Platypus Affiliated Society, and the problems with which it tasks itself, will also be introduced.

All are welcome--more importantly, all questions are encouraged.

The Second International (1889-1914)

Rosa Luxemburg

(1986) Directed by Margareteh von Trotta. Starring Barbara Sukova (Cannes Best Actress Award) and Daniel Olbrychski.

School of the Art Institute — Monday, September 2, 2013 | 6 PM

112 S Michigan Ave | Room 1307

Loyola University — Monday, October 7, 2013 | 5:30 PM

6450 N Kenmore Ave | Cudahy Hall | Room 301

University of Chicago — Wednesday October 16, 2013 | 6 PM

Harper Memorial Library | Room 151

The Russian Revolution (1917)

Reds

(1981) Directed by Warren Beatty. Starring Warren Beatty, Diane Keaton, Jack Nicholson, Maureen Stapleton and Gene Hackman. [Trailer]

School of the Art Institute — Monday, September 23, 2013 | 6 PM

112 S Michigan Ave | Room 1307

Loyola University — Monday, October 21, 2013 | 5:30 PM

6450 N Kenmore Ave | Cudahy Hall | Room 301

University of Chicago — Wednesday October 30, 2013 | 6 PM

1116 E 59th St | Harper Memorial Library | Room 151

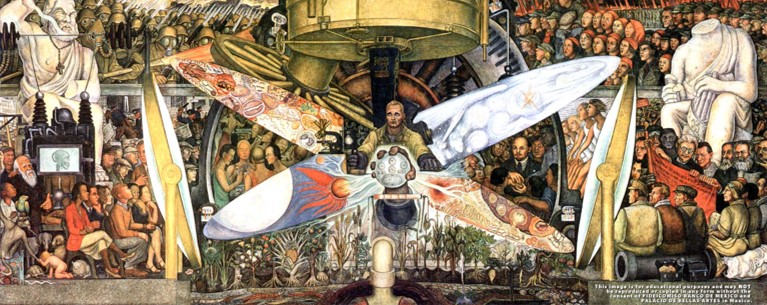

The Old Left (1930s)

Cradle Will Rock

(1999) Directed and Written by Tim Robbins. Starring Hank Azaria, Bill Murray, Joan Cusack, John Cusack, Ruben Blades, Emily Watson, John Turturro, Susan Sarandon, Vanessa Redgrave, Cary Elwes and Angus Macfadyen. [Trailer]

School of the Art Institute — Monday, October 21, 2013 | 6 PM

112 S Michigan Ave | Room 1307

Loyola University — Monday, November 4, 2013 | 5:30 PM

6450 N Kenmore Ave | Cudahy Hall | Room 301

University of Chicago — Wednesday, November 13, 2013 | 6 PM

1116 E 59th St | Harper Memorial Library | Room 151

The New Left (1960s)

Grin Without a Cat

(1977) Directed and Written by Chris Marker. [Trailer]

School of the Art Institute — Monday, November 11, 2013 | 6 PM

112 S Michigan Ave | Room 1307

Loyola University — Monday, October 18, 2013 | 5:30 PM

6450 N Kenmore Ave | Cudahy Hall | Room 301

University of Chicago — Wednesday, November 27, 2013 | 6 PM

1116 E 59th St | Harper Memorial Library | Room 151

Black Politics in the Age of Obama

MICHAEL DAWSON | CEDRIC JOHNSON | MEL ROTHEMBERG

An edited transcript of the event was subsequently published in issue 57 of the Platypus Review. A full recording of this event is available at our media website.

Monday, May 6th at 6:30 PM

University of Chicago | 1116 E 59th St

Harper Memorial Library, Room 103

The reelection of Obama presented a problem for the American left. Lost was the hopeful rhetoric of transforming society for the better, and as it became clear that Obama’s administration had returned to“politics-as-usual,” the left began to cynically appraise the purported gains made in his first term. Not the least of these was the claim that we live in a“post-racial” society. From Abolitionism to the Civil Rights Movement, the issue of racism was and is a defining one for the American left. As social life in the United States has reproduced itself through various social and ideological transformations, racism seemed always to reproduce itself in and through those transformations. And, surely not without merit is the contemporary left’s skepticism regarding America’s supposed achievement of a“post-racial society.” Yet, any talk of race in the current age must account for the fact that America’s first black president was twice elected by substantial margins. If anti-Black racism subsists, it clearly does not have the same relationship it once did to capitalism and society in general. This panel will investigate the how the left understands the concept of race in contemporary politics, and how this concept can, should, or will maintain of political significance for a future renascent left.

Questions:

1) There have been numerous theories of race and the manner in which racism has become society’s second nature. To be sure racism still exists; at the same time, the US has twice elected President Obama. Is there a theory adequate enough to explain this discrepancy between the apparent racism of American society, and the election of a black president?

2) In the 1960s, many on the left began to revise analyses of poverty solely based on class, adopting one that relied on the concept of race to explain the uneven distribution of wealth. Since this time, some progress seems self-evident, as minorities are now capable of holding lucrative leadership positions in large corporations and the highest offices of government. At the same time, glaring economic disparities persist on the basis of race. How is the concept of class relevant to discussions of race today? How are race and class related, and in what sense should we understand them?

3) Historically, going back at least to the “free labor ideology” of the mid-19th century Republican Party, the black question has been posed as a question of the emancipation of labor, with the radical Republican project being inherited by American socialists, the CPUSA, and New Deal labor leaders such as Adam Clayton Powell and Bayard Rustin. Similarly, at least viewed negatively, the crisis of the American labor movement and the concomitant disintegration of even the prospect of an American labor politics seems to crucially condition, if obscurely, the growing opacity of the black question in America.

4) Also since the 60s, a debate has arisen within the discussion of race, namely a rift between nationalists and integrationists. The former argue that the latter would have communal identity and black cultural particularity liquidated, while the latter argue that the former ghettoizes black political aspirations and misses the possibility to realize the potential of society as a whole. Today, is there a radical potential in either of these approaches? Which is more relevant to the concept of race in our society today?

5) In both of his election victories, President Obama was championed as a victory against the racism of the US populace. By the same token, Obama has been criticized by the left for adopting the policies of his predecessors. How does the contemporary left process this alleged victory against racism, in light of Obama’s acquiescence to politics as usual in the US?

6) The black question historically, though perhaps it has perhaps been most thoroughly politicized in the U.S., is by no means a strictly American problem. Rather, the legacy of racism seems to pervade global society today. And, indeed, from the galvanizing effect of English labor solidarity with the Union to the worldwide preoccupation with the Civil Rights movement, politicization of the black question in American has always been of the greatest political significance worldwide. So what now does the seeming marginalization of the black question in America tell us about the international situation the left faces today? How has the contemporary resolution, in the most conservative possible way, of the black question conditioned international leftism in our time?