Overcoming bourgeois right: An interview with Mel Rothenberg

Spencer Leonard

Platypus Review 34 | April 2011

On January 31, 2011, Spencer A. Leonard interviewed Mel Rothenberg, author of The Myth of Capitalism Reborn: A Marxist Critique of Theories of Capitalist Restoration in the USSR to discuss the theoretical underpinnings of American Maoism in the 1970s. The interview was aired on the radio show Radical Minds on WHPK–FM Chicago, on February 1. What follows is a revised and edited transcript of the interview.

Spencer Leonard: Last December the Platypus Review published an interview I conducted with a former comrade of yours, Max Elbaum. There I discussed the emergence, by the late 1960s, of the widespread impulse within the New Left towards reconstituting the Communist movement in the United States. Being older than Elbaum and having participated in the New Left as a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee [SNCC] in Chicago from 1961 onwards, you have a different perspective than him on the motivations behind the New Communist Movement [NCM]. What determined your joining a Marxist organization in the 1960s and how representative do you think your experience was? What do you take to be the continuities, both ideological and organizational, between the New Left and the NCM?

Mel Rothenberg: To answer that I have to say a bit about my background. It’s important because it’s shared with many others.

Like many of us in the New Left, I was a “red diaper baby.” We were the children of socialist activists, working class by and large, mostly in the two great movements of the “united front” of the late thirties and forties: the labor movement and the anti-fascist coalition. Those informed the experience of our parents. And as we learned at our parents’ knee, this fostered in us certain political perspectives, viewpoints, and orientations; one was to the labor movement and the working class, the other towards the threat to the working class movement posed by fascism.

Also I came of age in the McCarthy period. This wasn’t purely a question of oppression—our parents were often harassed and oppressed, we were not because we were young. Still, the period of McCarthyism marked a great disillusionment among a broad layer of the Left with Stalin and the bureaucratic and the police-state aspects of the Soviet Union. My father had been a labor organizer and a mid level CP cadre who had become disillusioned with the CP prior to Khrushchev’s revelations but had never totally broken his connection with his comrades. He greatly influenced my views. I don’t recall being totally shocked by Khrushchev’s speech. Mainly it confirmed in me my father’s doubts.

In consequence, throughout the early fifties many of us were politically passive. We were trapped in an ideological bind between Marxism and disillusionment with the Soviet Union. What brought us out of this were the Civil Rights and anti-war movements. These drew us back into political activism and created the New Left. The New Left reflected well our politics at the time, which were radical, social-democratic and interested in popular mobilization while eschewing hard Marxist ideology.

Two experiences of that era stand out. The first was in the summer of 1964 when the radical wing of the Civil Rights movement, having undertaken a massive mobilization of black voters, was rebuffed by the Democratic National Convention. Fannie Lou Hamer and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party were blocked from expelling that state’s racist delegation. The second key moment was the break in that year of Students for a Democratic Society [SDS] from the Democratic Party on the issue of the war. Many in the movement, even Martin Luther King, were moving in a similar direction, but SDS broke from “part of the way with LBJ” to an anti-Democratic Party position. This was painful because Johnson had been a progressive Democrat, responsive to the demands of the Civil Rights movement.

Two new perspectives emerged in this period. One was a strong identification with the revolutionary nationalism emerging within the militant wing of the African-American movement—Black Power impacted us very much. This also was painful because it involved the withdrawal of us white radicals from the center of SNCC and other leading militant civil rights groups. The other was anti-imperialism occasioned by the anti-war movement. These drew us beyond social-democratic, reformist politics. We sought a more radical, deeper break with the dominant system. This was the bridge between the New Left and the NCM.

SL: Turning towards Maoism by the late 1960s, you joined the Chicago-based Sojourner Truth Organization [STO] in which you were active for some years before eventually splitting with its leadership in the mid-70s. What about the STO appealed to you at that time? Why did the New Left’s turn toward Marxism manifest to such a large degree in a turn toward Maoism? What sort of reports did you have of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China and how did they affect your way of thinking?

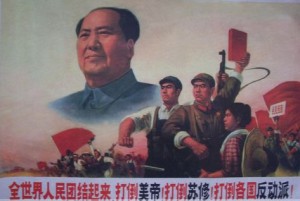

"All peoples of the world come together in solidarity to smash American imperialism, Soviet revisionism, and all adversaries of the Revolution!" Image printed in China, 1971, by the People's Fine Art Publishing House.

MR: Maoism combined the trends that had become dominant among the American New Left. They identified with revolutionary nationalism. This was also true of Vietnam, Cuba, etc., but China was the leading force. Moreover, they combined anti-imperialism with this. China became a leading voice of anti-imperialism in this country. Finally, there was a kind of left populism attached to this, anti-bureaucratism, a kind of Marxist participatory democracy or spontaneism. These corresponded to our disenchantment with the Soviet Union.

As for the Cultural Revolution, we understood it as both a necessity to avoid the restoration of capitalism in China as had happened in the Soviet Union, and as a means to lift the level of mass consciousness and to ensure thereby that revolutionary Marxism remained in command. By combining the Marxist tradition with these other elements I have mentioned, Maoism was a way back to Marxism for those of us who had drifted away from it in the fifties.

SL: How was it that you and others came to form a faction against the leadership of the STO and were eventually expelled? Did you already at that time harbor misgivings towards Maoism?

MR: The STO was, broadly, a Maoist organization, but it had its peculiarities. It didn’t look to China very much. It was the two central doctrines that defined it as an organization that both made it appealing and ultimately caused it to fail. The first was the “white skin privilege” doctrine that argued that the major task of American communist revolutionaries who wanted to mobilize the working class lay in getting white workers to repudiate the privileges derived from their skin color in order to forge unity between white and black workers. White workers therefore had to be made to understand that they were privileged because of racism and they had to abandon those privileges. Black workers, from this perspective, were the true revolutionary vanguard because they had the least to lose in the revolution.

The second defining STO doctrine was that trade unions had become bureaucratic and reactionary. They were organs of capitalism. What was needed was independent worker organization. This idea was taken from Gramsci, who developed it in his initial period of activism in Turin before the First World War. The leaders of STO argued that we were in a similar position to the Turin’s workers movement when it was moving beyond social-democratic reformism and class collaboration to a period of intense class struggle that would challenge the very foundations of bourgeois rule. For us to make a similar transition we had to transcend trade union hegemony over the working class.

Those two doctrines distinguished the STO on the Left. And as an organization they were serious, not least when it came to working class organizing. They were never a large organization but almost all their cadres worked in industry. I was one of the few that was not actually a factory worker and I was only allowed to join because I knew Mike Goldfield, who was already in and was working in a factory. They made an exception for me, but I was always somewhat marginal for that reason.

By the mid-1970s a number of us began to see the limitations of the organization’s positions. For instance, “white skin privilege” was not, unsurprisingly, a position around which it was easy to organize white workers. After all, workers are uninterested in giving up what little they have because they supposedly haven’t earned it. It also led to fights with unions that were not healthy. We opposed the union leadership not on broad democratic grounds by demanding more honest and effective unions, but simply on the grounds that unions were by their nature compromised organizations. This too did not sit well with politically conscious workers.

SL: Your criticisms of both of these two STO lines were given added salience at the time by an upsurge of union activity?

MR: The seventies were indeed a period of working class militancy. There was the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement in Detroit (DRUM) led by black workers with whom we had some connection. African-American workers had begun to form caucuses in unions and in certain plants. Also among the miners, steelworkers, and others there were oppositional caucuses critical of the union leaderships.

As for the STO’s Maoism, it was reflected in a kind of syndicalism, pushing for spontaneous workers’ uprisings. Our image of the Cultural Revolution as a series of actions where the workers took over the factory and met to discuss at great length topics such as bourgeois degeneration fit with our own syndicalist spirit. Still, our ties with Maoism were relatively superficial as opposed to other groups.

SL: When you finally broke with Maoism it took the rather dramatic form of a book-length refutation of the Maoist line that defined the Three Worlds Theory that appealed to so many. This was the claim that capitalism had been restored in the USSR, that it was engaged in a kind of imperialism. You have since referred to the book you wrote refuting this position, The Myth of Capitalism Reborn, co-written with Michael Goldfield, as a “settling [of] accounts with [my] Maoist past.”[1] Explain the capitalist restoration thesis and the attraction it exerted on your generation.

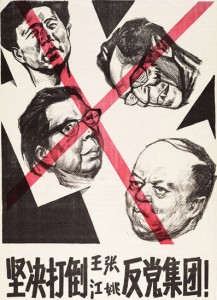

"Throw Out the Wang-Zhang-Jiang-Yao Anti-Party Clique!" Anti-Gang of Four poster from the late 1970s.

MR: The Chinese position was that a new bourgeoisie had developed in the Soviet Union under Khrushchev. They had gained control over the Communist Party (CPSU) to restore capitalism in a kind of bloodless coup. When China broke with the USSR and entered into a tacit alliance with the West it declared the Soviet Union the main enemy. They needed a theoretical reason why they would side with a capitalist power against a socialist power. Their initial assertion was that the USSR, through great power chauvinism, had adopted social-imperialism. This was followed by the deeper claim that the USSR had degenerated to a fully capitalist state. The order of this supposed development was important and shrewdly articulated because the initial claim played into the growing anti-imperialist sentiment around the world, and in particular to the growing Maoist movement in the U.S. The emphasis on social-imperialism initiated the sharp break with the traditional communist movement at the hottest flashpoint of conflict. Finally, the declaration that capitalism had been fully restored in the USSR made the break total and irreversible.

The theoretical basis of their analysis was very opportunistic and superficial. It followed a split that, in hindsight, was driven by nationalism and geo-political power conflict. The Chinese had a legitimate fear that the Soviet policy of peaceful coexistence with imperialism was designed to isolate them internationally. They also had legitimate concerns about how well the Soviet industrialization strategy would work in their conditions. Instead of developing a line to confront these real problems they tried to develop a position that would thrust China into the leadership of what they saw as a growing international communist movement critical of the Soviet Union, while at the same time justifying the cynical anti-Soviet alliance with the U.S. There was absolutely no chance of realizing these two contradictory aims. The smarter Chinese leaders must have known this. But, of course, the western Maoist movement lapped this stuff up, embracing this thesis with more enthusiasm than the Chinese ever did.

SL: Is this related to the narrative you gave before about the long experience of the New Left?

MR: We were trying to settle accounts with the Communist Party and the Old Left. By 1968, the developments in France in May, and the role the Communist Party played in them, not to mention the invasion of Czechoslovakia, gave added impetus to people already prepared to embrace this position. As a line, it was simple and direct, and many simply accepted it. It allowed them to silence their doubts as to why the New Left and the working class weren’t hand in hand everywhere in the world. What eventually prompted some of us to break with it in the mid-seventies were mainly the actions of the Chinese themselves, particularly in Angola. There, after the collapse of the fascist regime in Portugal and their abandonment of their erstwhile colonies, the Chinese opposed the left government to support Jonas Savimbi and UNITA, whereas the Soviets supported the opposition through their Cuban allies. The Chinese also supported the Shah of Iran, refusing to endorse the movement against him, in consequence of which a broad layer of Maoists began to question Chinese leadership. But Mike [Goldfield] and I explored the actual theoretical basis of the capitalist restoration thesis. Our initial substantive theoretical criticism was that the Chinese position implied that, though they couldn’t point to an actual capitalist class, there was a collective capitalism in the Soviet Union, that the bureaucracy constituted a capitalist collective leading the country back to capitalism. We felt this was incompatible with a Marxist conception of capitalism, which intrinsically involves competition among capitalists. You couldn’t have capitalism without capitalist competition, which was part of the essence of capitalism. This insight initiated our thoroughgoing critique of the thesis of the restoration of capitalism in the USSR.

In this country a single Maoist theoretician was most influential. This was Martin Nicolaus, the translator of the Grundrisse. Nicolaus was a theoretically sophisticated Marxist who joined the October League, which in turn eventually entered the CP(M-L), one of two major Maoist groups in this country along with the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP). He elaborated the capitalist restoration line in a number of articles in the 1970s, in which he tried to remain a kind of classical Marxist, but our own belief was that to do so required significant distortions of Soviet reality. For instance, on Nicolaus’s view, Khrushchev had imposed nothing short of a “regime of economic terrorism” on the working class through privatizations, semi-privatizations, and the development of a kind of wholesale market. Economic planning had been covertly undermined and enterprise managers had emerged as effective owners of the means of production. Thus they constituted a new, if legally unacknowledged, capitalist class. On the basis of isolated instances and sketchy data, he also argued that unemployment existed on a large scale in the USSR on account of the re-commodification of labor. Because Nicolaus argued that capitalism’s restoration was an ongoing economic process, he was compelled to exaggerate the social upheaval it occasioned in the form of unemployment, slowdowns and strikes, firings, and the imposition of stricter labor discipline.

SL: So, Nicolaus was addressing and perhaps rationalizing the exigencies of the situation. Because China had been aligned with Stalin until his death, the USSR must have been a revolutionary socialist society till then. Accordingly, even though workers in the Soviet Union were actually enjoying by the 1960s substantially increased levels of consumption, more amenities, social security, education, benefits, etc., Nicolaus nevertheless had to describe that situation in terms of the restoration of capitalism. Was that the tension you pressed Nicolaus on?

MR: Yes. Nicolaus identified as a sign of capitalist restoration any leisure or consumer goods the workers enjoyed, as well as any social differentiation, which, of course, also existed under Stalin. To do this he had to distort the facts.

SL: You also argued in the book that Charles Bettelheim had to change the idea of what capitalism is in order to advance the capitalist restoration thesis. For Bettelheim, not only was capitalism compatible with “state ownership of the means of production, of central planning, and of other economic features commonly thought to be socialist,” but, rather than one of the necessary preconditions for the achievement of socialism, the suspension or abolition of private property and the market in the USSR served somehow only to obscure the perpetuation of capitalism. The Soviet Union therefore represented a post-bourgeois form of capitalism. While defenders of the USSR argued, “look, there are no capitalists making money in this market, so it is not capitalism,” Bettelheim replied, “but capitalism does not require that.” What was Bettelheim trying to get at with this counter-intuitive mode of arguing and what was the critical issue at stake in your criticism of him?

MR: As the head of the Franco-Chinese Friendship Association, Charles Bettelheim was the leading French Maoist thinker of the time. He didn’t resort to distorting the facts. Unlike Nicolaus, he was a real expert on the Soviet Union. But arguing the restoration thesis demanded that he fundamentally alter Marxist theory.

Bettelheim accepted the position Mao enunciated in his left turn, when he was promoting the Cultural Revolution, that the key to building socialism turned on the line the party espoused. If it espoused a proletarian line, the revolution was advancing toward socialism. If it espoused a bourgeois line, no matter what the reality, the society was moving back to capitalism. For this reason, he did not view the restoration of capitalism in the USSR as a gradual process in the manner of Nicolaus. Whereas Nicolaus saw it as beginning with Stalin’s death in 1953 and culminating in Kosygin’s economic reforms of 1965, for Bettelheim, it was Khrushchev’s speech at the 20th Party Conference in 1956 that was decisive. The leadership’s plan, line, and practice determined the political nature of society in the transition to socialism. The argument was not so much that capitalism had been restored but that the process of its overcoming had been halted by the leadership. Even the theoretical question of whether or not labor is a commodity was a matter of the prevailing political line. If the workers are working to advance socialism, it is not a commodity; if they are not, it is. The crucial issue was why the workers are working. Bettelheim did not look for the immediate abolition of wages. He did expect, however, that socialist workers’ primary motivation was to “build the society,” which he thought was happening in China. Bourgeois right and the value form were thus to be overcome politically. The claim, bolstered by a certain romantic conception of the Cultural Revolution, was that Chinese workers were engaged in ongoing struggles to increase their control over the instruments of production. By comparison, mundane considerations such as workers’ material consumption, labor conditions, or the overall economic level were secondary. This is a species of voluntarism still runs through a lot of the Left, not only Maoism.

SL: This goes back to the picture you gave before of Chinese factory workers holding political discussions late into the night during the Cultural Revolution. The essence of Marxism for Maoists hinged, it seems, on constant re-politicization, enthusiasm, and mobilization. Rather than raising the question of how you can build socialism in a peasant country, it really became about political process. Emancipation in this context looks like one long university sit-in.

MR: Exactly! That was in fact what many Maoists believed. Facts did not really matter. One could not argue against Maoism on a purely factual basis. We took aim at that. We also proposed a theory of transition, one not so different from that of the leading Trotskyist thinker Ernest Mandel. In fact, Mandel wrote us a letter saying that he admired our book. At any rate, the main importance of the book was our argument against Bettelheim.

Drawing on the Grundrisse, Bettelheim centered his argument on the value form, arguing that under communism labor time will no longer be the measure of wealth. In that state, the economy will be so developed and automated that the production of all the material needs of life will take only a small percentage of collective human time and energy. From this perspective, commodity production, and thus the reproduction of capitalism, could not simply be equated with private production for profit. As long as labor remained the measure of value and was appropriated as surplus value by a ruling elite, capitalism continued to dominate. Thus, in the USSR, capitalism took a non-market, non-private-property-based form. State ownership of the means of production, central planning, and other economic features of the USSR normally associated with socialism, actually masked the existence of capitalism. Though there was nothing resembling a labor market, labor was subordinated to the production of value, and value operated socially as the measure of wealth. Obviously, such arguments were intended to relativize the significance of the Bolsheviks’ seizure of state power and of the economic changes wrought by the October Revolution. But it is difficult to understand how, on the ground of what Marx calls “bourgeois right” (which Marx acknowledges will continue to prevail during the transition to socialism), the value form, as its fundamental expression, would not also persist, particularly given the stalling of the world revolution. Overcoming the value form and harnessing the full liberating capacity of science and automation to achieve a society of genuinely human wealth is a goal that no Marxist would dispute. What Bettelheim demanded was that this be achieved, or almost achieved, early in the transition to socialism. Otherwise, the society inevitably collapses back into capitalism.

Beyond these theoretical issues, the basic political question is whether or not we have something necessary to learn from understanding the Soviet experience and its ultimate failure to reach its goals. The approaches of Nicolaus and Bettelheim are ultimately dead ends in this respect. I would contend that the Left cannot advance out of its current impasse until this question is addressed more squarely and with greater honesty than many seem inclined to do today. The sort of unspoken consensus on the Left that it is better to forget and bury the Soviet experience, and move on to a more emancipatory vision of socialism, won’t work. To overcome the past, you must face it.

SL: In an article in the January 2011 issue of Science & Society, you argue against a certain conception of “worker control of the means of production,” which, as you point out, can mean a number of things. There you argue that many who demand workers’ control of the means of production are actually demanding that “workers in each enterprise collectively determine what is produced, how much is produced, and how it is produced,” and that this is not Marxist.[2] How does this represent an attempt to short-circuit the specifically political aspect of overcoming bourgeois right, and thus a kind of repeat of the Bettelheimian Maoism you criticized in your book?

MR: There are two aspects to this. One is Maoism’s influence on Bettelheim, and the other is a certain Trotskyist tradition visible today in groups like Solidarity, who have a kind of syndicalist approach and see democracy in the plant as the key site of struggle. That tradition goes back to anarchism and syndicalism of various sorts. It is a very attractive view because it allows one to entertain the prospect of socialism in one factory. It makes the achieving of socialism more manageable. There is some of this in Argentine syndicalism. You achieve workers’ control factory by factory. Once you do it in every factory, you have socialism. It attempts to address problems of alienation, autonomy, and democracy at the level of the individual factory. This is very tempting in a period when the Left lacks political organization, or even substantial political influence. It also has a certain demagogical appeal, in that organizing at the point of production makes it easier to talk to workers about socialism. It is easy to talk about how stupid the boss is and say, “We can run this place much better and fairer. We could get more production. We wouldn’t have to deal with these foremen and bosses who are just parasites.” This kind of thing is, of course, popular among workers, especially when they are angry. It is easy to agitate around. It’s a very deep tradition on the Left, one the Maoist legacy plays into. Labor Notes and Solidarity are two groups coming out of this tradition that do serious work organizing in factories. I don't agree with it, but it is not a settled issue among Marxists.

SL: Trotskyism is obviously the tradition that insisted upon understanding the fraught political significance of the Soviet Union in terms of its historical character. In rejecting the Maoist line of capitalist restoration in the USSR, and describing the Soviet Union instead in terms of “process” and “protracted transition,” you arguably came close to a Trotskyist position, as Mandel’s approving letter seems to imply. How conscious were you and Goldfield, in the mid-1970s, of this? Were you actively reading Trotskyist works? If so, why did you never contemplate joining a Trotskyist organization, whether in the 1960s or later?

MR: My perspective is a little different from Goldfield’s. Both of us read a lot of Mandel’s works. Clearly we were influenced by his analysis, which goes back to Trotsky. But my problem with Trotskyism was twofold. First, the Trotskyist groups I knew to be doing serious work in plants and factories, groups like Solidarity, had what I have called a syndicalist orientation. I respected what they were doing, in terms of organizing workers. But the syndicalism was, nonetheless, always a problem for me. They had in fact adopted a more nuanced version of the position STO adopted toward trade unions. They were active in trade unions, but they would always form an oppositional bloc, refusing to work with the existing leadership. They would never work with them, as a matter of principle, considering them to be irredeemably corrupt and compromised. I felt that this was an ineffective way to organize workers.

SL: A Marxist position, in your view, entails intersecting workers in their own organizations that serve as their schools of politics?

MR: Right. The Marxist position requires working with trade unions. There may be corrupt or even tyrannical leaders, whom one would oppose, but in a way that respects that there is a structure and a leadership. The workers can choose a better leadership, but that involves a complex struggle. One cannot simply dismiss the existing leadership on the grounds that they are a bunch of corrupt opportunists and we have to do something totally different. This was an important political point against at least a certain wing of Trotskyism.

My problem with the other wing of Trotskyism, represented by groups like the ISO, is that they do not believe in the United Front. For me, the way to build a movement for socialism is to build a multi-class historic bloc. This does not mean that every class has the same role, or the same leadership, but it will include the middle class intelligentsia and many skilled professionals, the sort of people required to manage a modern industrial society. This is a protracted process. Trotskyists do not really believe in this and have a purely proletarian position. Their view is that you go in and you try to rile up the working class. It is like the old Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP) line, “a single match can start a prairie fire.” Excite the working class to rebellion and then parachute in as a vanguard. Take over the leadership once the working class has attained a certain level of combativeness, then lead it toward revolution. That strategy has never worked.

SL: In your recent Science & Society article you write, “One of the great and sad lessons of the Soviet experience is that after 70 years of uninterrupted communist rule, the Soviet Union rather easily and quickly reverted back to a deformed but thoroughly capitalist society. The roots of the socialist order turned out to be weak and shallow.”[3] How does this relate to your understanding of the wider collapse of the Left? After all, haven’t the roots of the socialist project proved weak and shallow worldwide? Does the Soviet experience not raise the question of the self-defeat of the Left?

MR: This is the key question. We are not going to get a serious Left until we confront the collapse of the Soviet Union. Broadly speaking, three explanations are usually offered. The first is basically the capitalist view, which is that any kind of socialism is incompatible with modern industrial society. It can't work, and didn't. The second position, which is the position of much of the old Communist Party Left, is that the conditions were just too harsh. The Soviet regime was born in the midst of crisis; there was a civil war, then there was famine; there were attacks from the outside; there was a second world war. We faced the continual hostility of the capitalist world and the working class of Russia was too backward to rise the to occasion. So, we had the right approach, but ran into a series of insuperable obstacles. There is a certain amount of truth to this, but I don't think it an adequate explanation. For one thing, the conditions in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, when they held power, were much harsher than in the 1980s when they lost power. So the collapse was not directly rooted in the harsh conditions of people, or the hostility of the capitalist world.

My explanation would say that they went about it the wrong way. Building a socialist society cannot occur primarily through a party state, which is what they did in the Soviet Union. The motive force was the party apparatus, and the entire project of building socialism was concentrated in it. The masses of people were told to shut up and work, and leave the socialism question to the party. That was the dominant position and practice in the Soviet Union. But socialism cannot be built by a political apparatus, which inevitably stagnates, has its own parochial interests, preoccupies itself with its own retention of power, and cannot in itself lead this kind of project. You need to have, as Gramsci put it, a historic social bloc committed to the socialist project that is much broader then a party-state apparatus. There are of course difficult questions of class relations, the hegemony of the working class, governance of the state, the structure and nature of a political party representing a broad social bloc, involvement in electoral and more revolutionary forms of struggle, etc., all of which can only be resolved over a long period of practice and struggle. In the Soviet experiment they tried to short-circuit these issues through the dictatorship of the party-state apparatus. It ultimately precipitated their failure. |P

Transcribed by Alex Gonopolskiy and Ryan Hardy

[1]. Mel Rothenberg, “Some Lessons from the Failed Transition to Socialism,” Science & Society 75:1 (January 2011): 114.

[2]. Ibid., 118.

[3]. Ibid., 117.