The unchanging core of Marxism: An interview with Ian Birchall

Efraim Carlebach

Platypus Review 102 | December 2017 – January 2018

On October 14, 2017, Efraim Carlebach interviewed Ian Birchall at Birchall’s home in Edmonton, north London. In 1962, Birchall joined the International Socialists, a tendency led by Tony Cliff and the organizational forerunner of the extant Socialist Workers Party (UK), founded in 1977. Though he is no longer a member of the Socialist Workers Party, Birchall has remained a leading figure of the International Socialist tendency for over half a century. He is the author of numerous publications including the 2011 biography, Tony Cliff: A Marxist For His Time[i]. What follows is an edited transcript of the interview.

Efraim Carlebach: How were you first politicized in the late 1950s and early 1960s? What were the chief concerns that drew you and others of your generation into politics?

Ian Birchall: I was at a very elitist, middle-class grammar school and I developed various oppositional attitudes, but often over things that were not particularly serious, like the monarchy. It was really only when I went to university that I became involved in politics. I was involved initially with the Labour Party. This would be the time of the famous Scarborough conference in 1960, when the Labour Party adopted nuclear disarmament against the wishes of the party leaders, so there was a huge internal fight in the party. I was on the nuclear disarmament side. I marched in two or three of the famous Aldermaston marches. On the way I encountered one or two Marxists, particularly, initially, people from the Socialist Labour League, the Healyite organization, who made quite an impression on me. But it was an ambivalent impression, because I thought they took themselves too seriously and I thought that their perspective was flawed: It was around this time, in the early 1960s, that they were talking about the immanence of fascism in Britain, of which there was very, very little sign.

In Oxford I was in the Labour Club. It was in this student milieu that I first encountered and got involved with a group of people around what were then called the International Socialists (IS), the forerunners of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP). When I had been with the Labour left, with the “Tribunite” left—Tribune was the main organ of the Labour party left, and I had read Tribune devotedly—somehow, although I agreed with it, I found it intellectually unsatisfying. Whereas people like Tony Cliff, Mike Kidron, and Alasdair MacIntyre were enormously impressive speakers and gave the impression of having an analysis that fitted what was going on in the world, a thoroughgoing revolutionary critique of British society that, at the same time, actually fitted the realities, which were in many ways very non-revolutionary.

So, I was pulled into the International Socialists. I joined in December of 1962. The work we did—we built a branch of about 20 members at the time in Oxford—was done entirely through the University Labour Club. I had not realized when I joined what an incredibly tiny organization the IS was. It had something like 106 members. When I was told 106, I said, “Is that in Oxford or is that the whole country?” I was rather disappointed when it turned out to be the whole country. But, of course, promotion was very rapid, so I found myself, within a couple of years, on what was called the working committee but was actually the executive committee of the organization. For a time, I was the editor of the paper. I was going around speaking. I was generally a leading figure in the organization, which my abilities and knowledge at the time certainly did not justify—but that was the nature of the organization.

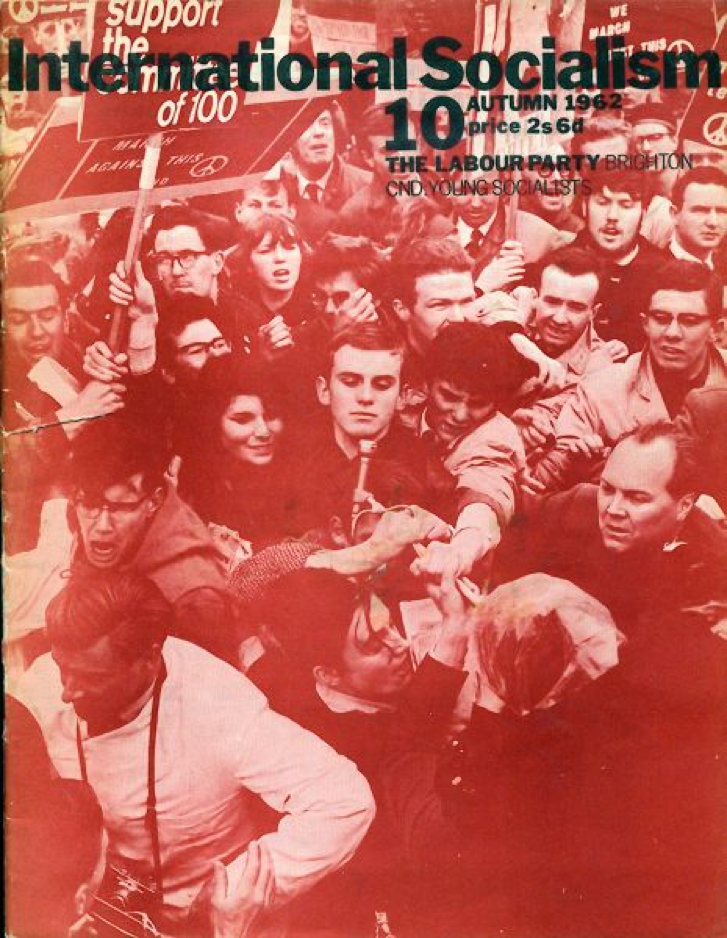

A demonstration in support of the Committee of 100, a British group founded in 1960 to organize mass nonviolent civil disobedience towards the political aims of nuclear disarmament and peace, as pictured on the August 1962 cover of International Socialism.

EC: In your biography of Tony Cliff you write about the Young Socialists.

IB: Young Socialists was set up by the Labour Party basically as a response to the nuclear disarmament movement. They saw all these young people marching through the streets and expressing radical ideas and they wanted to pull those people into the Labour Party. So, the Labour Party, which for several years has not had a national youth organization—local parties just had their own youth section—set up a national youth organization. And of course, all the far-left groups, all of which were tiny, moved in and started to try to recruit. The Socialist Review Group (SRG), which became the IS in 1962, probably had 30 or 40 members when the Young Socialist was launched in 1960; the majority of people who were pulled into the IS in the following period were pulled in through the Young Socialists. Gerry Healy’s group, the Socialist Labour League (SLL) probably had 200 members. We had a paper called Young Guard, which was a joint enterprise between us and Ted Grant’s Revolutionary Socialist League (RSL) and one or two other Fourth International fragments. The Grant group was less prominent. They maintained themselves, actually—this is to their credit, I suppose—by the fact that they stayed in the Labour Party for 20 odd years and built a real base for themselves by so doing. The SLL walked out of the Labour Party in 1964. We drifted out over the next two or three years.

EC: So, the Labour Party created this youth organization to try and tap some of the energy from the nuclear disarmament movement, which is an early New Left movement, and the Trotskyist groups on the far left—the SRG/IS, the SLL, and the RSL—all tried to recruit in it. You were obviously attracted to the SRG/IS, but you said that you had had some engagement with, but were more skeptical towards, the SLL. What was the substance of the debate between those groups and what drew you to the IS?

IB: First, there was the whole debate about Russia: was the Russian state capitalist or a degenerated workers’ state? This could become (and often did become) a very sterile debate, but it had a real substance to it. First, it meant that the SLL were more sympathetic to Stalinism than I would have wanted to be, suggesting that there was somehow some sort of socialist content to the regime that existed in Russia, China, and Eastern Europe. But there was also the whole question of the state, of defining socialism in terms of state ownership: “Where’s the stock exchange in Russia? You are asking for nationalization in Britain. They’ve got nationalization in Russia!” That was the sort of argument you used to get from the SLL, and it made the whole debate about state capitalism really take on more significance for me.

We had a critical attitude towards nationalization. We would not see nationalization as an end in itself. At the same time, we would call for nationalization. Our position would have been nationalization under workers’ control, or nationalization with workers control—that nationalization on its own, simply taking a particular industry out of the hands of private owners and putting in the hands of some board of bureaucrats, was not in itself a great gain for the workers.

Secondly there was a question of perspective. The SLL’s perspective was a very short-term perspective, suggesting that there were going to be massive confrontations in the immediate future, when there was not actually evidence of that in the early 1960s. That was coupled with their completely irresponsible behavior in the Labour Party. They forced a confrontation with the Labour Party in order to get themselves expelled, which they did very rapidly, so that they could then set up an independent organization. It seemed to us that that was not viable. What they built—it is undeniable that they did build something—was an organization of a few thousand people, at best. They had a daily paper, although I do not think having a daily paper really did them a lot of good; I do not think they had the kind of organization which could have benefitted from a daily paper. Anyhow, in a sense they became less and less significant to us. When we were in the Young Socialists we were constantly confronting the SLL. Once we moved out of the Young Socialists we did not see them very much anymore.

Now, of course, you can say, “Look at 1968! Everything changed.” The period I am talking about, 1963-64, was only four years off 1968, but we had no idea what was coming. We could see a rise in the level of struggle, and there were things going on, particularly when the Wilson government was elected. But the SLL’s perspective was much too short-term, with the result that when things did start moving, they actually placed themselves outside of that movement. They did not take any part in whole movement that grew up around Vietnam, for example.

EC: So, there was a difference between the SRG/IS and the SLL in terms of the orientation towards the Labour Party?

IB: Yes. We became more and more critical of the Labour Party once the Wilson Government was elected and preceded to do a whole number of things that we were strongly opposed to, and we moved away from our Labour Party orientation. We were trying to take people with us. From the adult Labour Party we took only a handful of people; it was mainly from the Young Socialists that we took people. But we did not have the kind of confrontation with the Labour Party that the SLL did, which I think was unhelpful in terms of building a movement.

EC: What kind of political education were you receiving in this period and how was that taking place inside the IS?

IB: We had weekly branch meetings at which there would be a political topic. The speaker would be one of the more experienced comrades. I was in the Tottenham branch just down the road from here. From time to time we would have a speaker like Tony Cliff or Mike Kidron, every three-six months, and then we would have some of the younger comrades, who were often learning. I did a fair amount of speaking around other branches in London at this time and it was an educational experience for me to prepare the talk. I would get asked to speak on things I did not know a whole lot about. That would be the main educational mechanism, together with the various books and articles that were being published. International Socialism the journal was incredibly important in terms of education. We had debates on arguments like “reform or revolution.”

In the period just before I got to London, Tony Cliff used to do an educational series of 12 lectures on basic Marxism in a number of different places. I think there is a printed version of them somewhere, but a printed version of one of Cliff’s lectures is not the same. His speaking style, the way he exploited his bad English, the way he would insert jokes into the speech, and so on, made him an extremely unorthodox but extremely impressive speaker. Lots of people who were drawn towards the movement in this period will testify to the impressiveness of Cliff as a speaker.

EC: Cliff is coming out of a Trotskyist tradition. To what extent did you consider yourself a Trotskyist at this time? What would that have meant in this period?

IB: That is a very interesting question. Initially, probably up to 1968, most of us would have said we were not Trotskyists. We would have said that because we wanted to distinguish ourselves from the SLL. That was partly in purely pragmatic terms; the SLL were being witch-hunted in the Labour Party for being Trotskyists and we wanted to make clear that we were a different organization. Also, we would have wanted to dissociate ourselves from the sort of things the SLL, and to some extent the other Fourth International groupings, identified with Trotskyism and made central—In particular: the question of the nature of Russia, the defense of Russia as a workers’ state of some sort, and also the adherence to the Transitional Program. At the same time we saw ourselves as being derived from Trotsky as being the most coherent critic of Stalinism and as representing internationalism, in particular the rejection of socialism in one country. So I think you would have probably gotten different answers from different people if you had asked us if we were Trotskyists.

EC: There are older people like Cliff and Kidron coming out of what we would now call the ‘Old Left’ and educating a new generation of people like yourself coming up in the New Left. There is obviously both change and continuity between the two. How did you understand this change and continuity at the time? Why was it that a ‘New Left’ was needed? What were the tasks that you inherited from the Old Left?

IB: When you use the term ‘New Left’ you have got to be careful, because when we used the phrase ‘new left’ we were thinking particularly of the milieu around New Left Review and we always dissociated ourselves from that, because we saw it as a heavily academic milieu. They used a rather pompous, obscure language in their publications. They were very largely confined to the intellectual milieu; they did not really have any working-class base. I am not saying we had a huge working-class base, but, with things like Cliff’s book on incomes policy, we did have an orientation to the shop stewards’ movement. So, I do not think we would have thought of it in terms of this Old Left/New Left dichotomy. But at the same time, we did identify ourselves as somehow being a new generation and thought that we were going to avoid some of the mistakes of the older generation.

EC: What did you identify those mistakes as being?

IB: Well, on the one hand, the whole experience of Stalinism. The pre-1956 generation really had, with very few exceptions, been very uncritical towards Stalinism. And on the other hand, the whole Labour Party orientation, the whole Bevanite experience and so on. We wanted to avoid both of those and create something that would be independent of, and critical of, both Stalinism and old-style social democracy (which was still very strong: the Labour Party in 1964 was a very different kind of organization from what the Labour Party is now, even with the Corbynite upsurge, for however long that will last).

EC: Those were some of the changes. You wanted to differentiate yourselves from the two options of Stalinism or social democracy. What were the things that you saw as being continuous between the previous generation and yourselves?

IB: It was always important to us to look to the tradition of the Russian revolution, and particularly to the early years of the Russian revolution, to notions of working-class democracy, particularly as expressed in the soviets, and to the idea of direct working-class power. There is always a danger of over-simplifying here, but Trotskyism had stood for what was best about the early years of the Russian revolution as against the way that had been distorted and betrayed by Stalinism in the subsequent years. Of course, all sorts of torturous debates then come up about Kronstadt. But we perceived ourselves and the tradition we adhered to going back to 1917, and before that to the Paris commune, as distinct from this tradition of Stalinism and social democracy.

One thing that was particularly important for me and for a lot of people of my generation was Hal Draper’s little pamphlet, The Two Souls of Socialism where he talks about socialism from above and socialism from below, with Stalinism and social democracy both being forms of socialism from above. We would have regarded that distinction as very important. One of the early issues of International Socialism reprinted the Draper pamphlet. It was reprinted in various journals at that time, including the Labour student journal, Clarion. That pamphlet and those concepts were very important for me, and when I talk to other people 30 or 40 years later, they say it was very important for them, too.

EC: You have talked about a tradition coming from particular revolutionary moments: the Paris Commune of 1871 and the Russian Revolution of 1917. Where does Marxism fit into that? Were you seeing yourselves as inheriting this tradition of those moments, or of Marxism more generally? What would Marxism have meant to you at the time?

IB: I certainly was, in a rather disorganized way, reading Marx. Just before I joined the IS there were two volumes published in Moscow of the selected works of Marx and Engels—about 1,200 pages which were remarkably cheap. I remember devouring those, reading my way right through those two volumes and wanting to know more. And then I read considerably more. I read at least the first two volumes of Capital and parts of the Grundrisse over the next five or ten years.

I certainly did not regard this as having some sort of religious status. Cliff was always very clear on that, certainly in the period before 1968: the writings of Marx or Lenin or Trotsky were not to be taken as scripture, not to be taken as some sort of religious text. They were to be read critically. But on the other hand, this offered a framework: all history being the history of class struggle, nature of the state being a weapon of one class against another, etc. Those sort of basic principles offered the beginning of an analysis, of an understanding of how the world worked and fitted together.

EC: Now we have discussed the period leading up to 1967, when the anti-Vietnam War movement took off in Britain.

IB: Some of us had been involved a little before 1967, but yes, in ’67 it took off with the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign. The Vietnam Solidarity Campaign was basically run by what became the International Marxist Group (IMG), which was another fragment of the Fourth International. The relations between them and the Grant group are very complex and I will not attempt to go into them. We set up the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign—the IMG did, with some involvement from the IS. This was against the British Council for Peace in Vietnam, which was basically run by the Communist Party and the Labour left, and which took a very soft line which simply called for negotiations. We took the stance that there was a clear line of division and we were in favor of victory for the National Liberation Front, because this was a struggle for national liberation against imperialism. That slogan started drawing people.

In October 1967 there was quite a big demonstration, and then a much bigger one in March 1968, building up to a very large demonstration in October ’68. This had a lot of repercussions in the universities, reinforced by the French events of ’68—but there was a student movement beginning to explode in Britain even if the French events had not happened. This provided a milieu in which the IS could operate. We responded to it and we drew people in. When I joined in 1962 the IS had just over 100 members; by 1964 it would be 200; by the beginning of 1968 it would be 400. By the end of 1968 we probably had a membership of over 1,000. That was primarily out of the student movement and the Vietnam movement.

EC: You mentioned seeing yourselves in the tradition of Marxism, however in a critical manner, and you characterized Marxism as offering a framework. How was the IS distinguished by a Marxist approach to the Vietnam War as compared to other groups that were involved in Vietnam solidarity at the time?

IB: It is difficult to say. I am not sure that we did have a terribly distinctive line, except that we were much more oriented to activity in the British working class, which would have been in two things. First, we were around the Shop Stewards Movement, around the whole argument about incomes policy, and we were promoting Cliff’s book. For a time, we were promoting the London Shop Stewards Defense Committee, which arose out of a victimization case. Secondly, we were around tenants’ struggles. There was a big campaign around rent increases for council tenants, particularly greater London council tenants, and we were heavily involved in that.

Our position was always to oppose the Vietnam War but to see the Vietnam War as a product of the capitalist system. We have to fight the capitalist system at home—Liebknecht’s famous slogan was “the main enemy is at home.” I suppose that was our distinctive position. And, of course, we were accused of “economism” by the IMG; that was the word that was thrown at us most commonly. Whether it bears any real relation to what the word had meant historically, I do not know. They meant that we were spending too much time immersing ourselves in very localized economic struggles about wages, trade union rights, tenants’ rights, and so on, when we should have been addressing the global question of American imperialism. That would be the dividing line, but it was a fairly fraternal dividing line. We worked fairly closely with the IMG people and others in the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign.

EC: In your biography of Cliff you mention that younger members like yourself quite quickly became involved in the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign but that Cliff and Kidron, the older leadership, were perhaps more ambivalent at first.

IB: That is true. There were two issues. One is that in theoretical terms they thought that American imperialism could survive the loss of Vietnam—which of course it did, very easily. Kidron argued that U.S. imperialism did not have any major economic interest in maintaining its involvement in Vietnam. Therefore, he did not believe it was a rational for the U.S. to invest so much money and resources in Vietnam. Kidron was making a critique of the classic Leninist theory of imperialism, which was still accepted as dogma by most of the Trotskyist currents in Britain. From this critique, he made a strategic argument, rejecting the Third Worldism which characterized much of the revolutionary left and much of the left more broadly. When the war was just getting going I suggested we publish an editorial about it in International Socialism. He said with complete scorn that we should not bother with “that silly little war.” As he put it, “to believe nowadays that the short route to revolution in London, New York or Paris lies through Calcutta, Havana, or Algiers, is to pass the buck to where it has no currency. To act on this belief is to rob the revolutionary socialist movement of the few dollars it still possesses.”[ii] In his book Western Capitalism Since the War, which was published in 1968, Kidron refers to “the American decision to withdraw from Vietnam”—already in 1968!

Of course, in one sense Kidron was right. The peace talks did begin in 1968 and the Americans got out of Vietnam. The Americans were a bit cautious about foreign wars until the 1990s because of Vietnam, but it didn’t do them a whole lot of harm. Kidron was right.

On the other hand, what Kidron got wrong was, firstly, failing to understand that states sometimes act irrationally,[iii] and secondly, underestimating the political importance of a mass movement against the war in the U.S. and around the world, and how this opened new horizons for the revolutionary left. Think of the political events of those years from 1968 to 1975, the number of people who were drawn into activity, the number of ups and downs of the movement (like the Kent State killings). Kidron had this gift for seeing long-term historical tendencies and missing the short-term ups and downs that were involved in them. Some of us—some of the younger ones—were a bit more sensitive to that than Cliff and particularly Kidron. I do not think Kidron ever really became involved in the politics of Vietnam.

In Cliff’s case, he had a long, long history in the Trotskyist movement and this had always been a history of isolation. The Trotskyist movement was right on the fringes of any real movement. In the 1960s, when we began to do things like the Shop Stewards’ Defense Committee, the various tenants campaigns, and so on, Cliff was very, very keen that we should involve ourselves in that—that this really was the beginning of the Trotskyist movement getting itself back into the mainstream of the working-class movement. Therefore, Cliff initially thought that Vietnam was a bit of a distraction. He changed his mind quite rapidly on that. But it is true that it was younger comrades, particularly Chris Harman—Chris Harman deserves most of the credit for this—who shifted the IS towards a greater involvement in the Vietnam movement and away from what would have been a very abstract negative position.

EC: What was the significance of the events of May 1968 for this turn in the IS?

IB: You have to see this on two levels. One was the level of what was going on, the sheer excitement and the monumental significance of suddenly seeing 10 million workers not just on strike, but occupying their factories. We probably did not realize until later the extent to which at least some of those occupations were bureaucratically manipulated, but certainly this had begun quite outside the control of the bureaucracy at Sud-Aviation in Nantes on May 14, when they voted for indefinite occupation. In various factories workers were locking the management up in their offices and generally taking the place over. We had talked in the abstract about how “the working class has the power to take over society.” Suddenly it seemed to be happening under our noses. The sheer excitement of that, the sheer impression of that, was enormously important for us. It confirmed what we had been doing. It gave us a sense that what we had been doing was right and that it was possible. Before May 1968, if you had an argument about whether the working class could actually take over society, you would be dredging up examples from 1917. Suddenly it was happening right on your television screen.

At another level—and this was very important in terms of Cliff’s position—what happened? By the end of June, they had all gone back to work and De Gaulle had won an election with an increased majority. How had this movement that seemed so incredibly powerful actually collapsed so quickly? Cliff began to argue that this happened because there was not an alternative political leadership. The Communist Party still had this grip over the French working class and there was no organization able to challenge it. There were various small revolutionary organizations in France, with which we had contacts—some of them came over and we interviewed them and organized a public meeting at which they spoke—but they were all far too small. There had been significant moves towards producing some sort of unified organization in France, but they had not gone very far.

So, Cliff was saying that we needed a revolutionary alternative. There was a call for left unity here. We made proposals for a united organization to all the other groupings to the left of the Labour Party. Second to that, the IS transformed itself into a much more centralized organization and adopted the principle of democratic centralism for the first time. We had never talked about democratic centralism previously. Those were the changes, and it was a rather frenetic year, with a large numbers of internal documents, factions being formed, and very heated debate.

EC: In your biography of Tony Cliff, you quote him saying that the student movement went up like a rocket and came down like a stick. Looking back now, to what extent do you agree with Cliff’s analysis of the failure of the New Left in 1968? Would you say that there were other failings of the movement at that time?

IB: Well, there are a whole lot of things you can say there. The biggest failing was that we were too small. There was not a major confrontation in Britain in 1968; the real test in Britain did not come until 1972-74, with first the miners’ strike and then the imprisonment of the dockers. There was a real confrontation. We, as an organization, did not have the necessary influence, but there was a shift in the balance of forces, going through to 1974, when the second miners’ strike brought down the Heath government and put Wilson in power. That is the only time, as far as I know, that has ever happened in Britain. So, Cliff was right to look at the situation and see how much was at stake. He was right in saying that we needed to build an independent organization. Could we have done many things rather better than we did? I am sure we could have. But we never had an organization remotely large enough to actually make a real difference.

From 1968 onwards there was a revolutionary wave across Europe that went on to 1975 in Portugal. We underestimated the capacity of social democracy to regain control of the situation in both Britain and Portugal. In Britain the Labour Party regained control with the Social Contract policy. In Portugal the Socialist Party grew and regained control under Soares. We failed to see that and to respond to it effectively. I am not at all sure what we could have done. I do not think there is any sort of magic formula—that if only we’d had the correct slogan, then everything would have been better. I do not think history works like that.

EC: In the 1970s, to what extent did the choice facing Marxist groups such as the IS appear to be between either sectarian isolation or liquidation into the Labour Party?

IB: I do not think liquidation into the Labour Party was ever an issue in the 1970s. Apart from the Militant, which stayed there, nobody was in the Labour Party in the 1970s. It was only at the beginning of the 1980s that you get this start of a swing back into the Labour Party. But I do not think the alternative to joining the Labour Party was sectarian isolation. One of the most important things we did in the 1970s was the Anti-Nazi League. Whatever you might want to say about the Anti-Nazi League, I do not think sectarian isolation is the phrase that fits it. The Anti-Nazi League was a very successful operation in terms of drawing together a very broad range of support. When I look back on it that is one of the things I feel we deserve most credit for.

EC: You write in the biography of Tony Cliff that the Anti-Nazi League was the major contribution of the 1968 generation—that it was really spearheaded by people who came into the group in 1968. Could you explain a bit about what the Anti-Nazi League was, how it got started, and what its significance was for the IS?

IB: We were involved from the very beginning. That goes right back to 1968 and Enoch Powell’s famous “rivers of blood” speech, which was followed by the London dockers marching in support of Enoch Powell. One of our docker members, Terry Barrett, opposed the dockers’ march, as did the group of people in the IS who worked with Barrett and who we built up. At the time we failed. We did not stop the dockers’ march. But we were known as the people who were opposed to, who were fighting, racism in that way. And we drew people around us who then played an important role in setting up the Anti-Nazi League a few years later.

From quite early in the 1970s there was a growth in the far-right, particularly the National Front, which was having some significant success in standing in elections. It was not winning in any elections but it was picking up a lot of votes. It had a lot of support in that sense, electoral support. It also was building up support in terms of a street-fighting cadre. It could bring out several hundred street fighters, perhaps at best one or two thousand, for demonstrations in public. They could not mobilize their more passive, electoral support into support on the streets because whenever they went onto the streets we challenged them. There were a whole number of confrontations—particularly in 1977 at Wood Green and then at Lewisham—where they came onto the streets and we confronted them and they came off rather the worse for it. That was an important setback for them.

With the forming of the Anti-Nazi League we actually drew in a very broad range of people, including a lot of Labour Party people. Neil Kinnock was a leading sponsor of the Anti-Nazi League; he was working his way up the Labour Party ladder and showing his left face. (He would show his right face a few years later.) Here in Tottenham we had quite a lot of activity around the National Front trying to hire rooms in local schools to hold their meetings. We tried to oppose this by getting pickets on the schools to prevent them from holding the meetings. That was done by drawing in a broad range of people, people who would not have considered joining the IS (and quite a few Labour Party people in particular). This happened on the national level; we had these names, and that could then be used as support. There were two major carnivals held in London and one or two elsewhere in the country with some quite well known bands, plus well-known speakers from the political left, including Labour Party people. At the biggest anti-Nazi demonstrations—one in Victoria Park in the East End in the spring of 1978 and then one in Brixton in the autumn—we managed to mobilize between 50,000 and 100,000 people. There were also lots of local activities against National Front activities in various areas. Instead of demanding that the council come and paint out their slogans, we just took out people with buckets of whitewash and painted them over. This involved a very considerable number of people and it was one of our main contributions in that period.

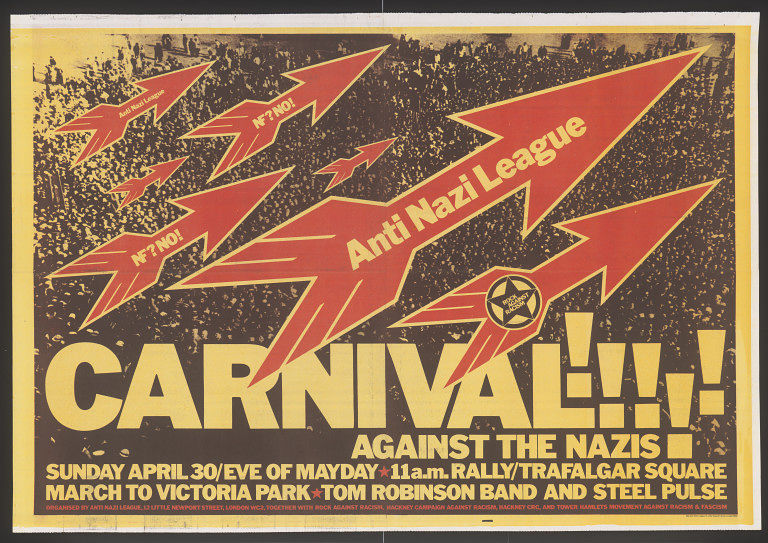

Poster for Carnival Against the Nazis sponsored by Rock Against Racism in 1978, designed by David King

EC: When did the activity around the Anti-Nazi League began to wind down? Why did that happen?

IB: I suppose it happened by 1978. It was not so much us winding down as it was the National Front winding down. After Lewisham they tried to stage a comeback in Manchester in the Autumn of 1977, which was really a great flop for them. They only got a few hundred people. I think they then had a split of some sort. They were clearly and visibly in decline, but we did not just give up; we carried on. I remember being on demonstrations right up to the time of the general election in 1979. It was during one of those demonstrations in the immediate run-up to the ‘79 election that Blair Peach was killed. There were a lot of people still involved, but there was a winding down in the sense that the National Front were now in retreat.

What was also happening, although perhaps not quite as vigorously as we might have hoped, was a revival of the industrial struggle. In 1977 a big firefighters strike lasted several weeks. In 1978 there was the Ford strike. Then, in the beginning of 1979, in the period immediately prior to the general election (known as “the winter of discontent”), there was quite a wide range of strikes, particularly in the public sector. Some of them were very militant strikes, strikes in which there were elements—I would not want to go further than that, but there were elements—of workers control, of workers not just stopping work but demanding to control how their work happened. Health workers were saying, “Emergency cases only, and we decide what counts as an emergency!” There was that shift back to the industrial struggle and we attempted to move along with that.

EC: You mentioned before that the analysis of the IS after 1968 had been that the problem was the lack of a revolutionary alternative, whether to the Communist Party in France or to the Labour Party in the UK. To what extent was that still the analysis in the period we are discussing now, the industrial actions of the late 1970s and early 1980s? Why did an alternative to the Labour Party fail to appear at that time?

IB: That is the fundamental question, isn’t it? The analysis that what was needed was to build a revolutionary alternative, particularly to the Labour Party, continued. This was a period of huge crisis for the Communist Party, which went through a number of splits and internal disputes and eventually wound itself up by the end of the 1980s. While it never had very much influence electorally, the Communist Party had, since the 1930s, been at the center of a network of industrial militants and had been able to control industrial struggles. That was coming to an end. We wanted to replace the industrial role of the Communist Party, first, and then perhaps rather further ahead, the political role of the Labour Party. We failed to do that.

Now was that because we did something wrong, or because the objective forces were just too strong? I tend to be very skeptical of any account that says it was because we did something wrong—that if we had had the right slogan, that if we had had the right transitional demand, that if we had been more economist or less economist, or whatever, then we could have built the revolutionary alternative. There were lots of people around who were talking about doing precisely that and none of them did it, in fact.

In general, the revolutionary left probably got weaker in the 1980s. I suppose we became in many ways much more of a propagandist organization, but we held ourselves together throughout the ‘80s. We were centrally involved in supporting the 1984-85 miners’ strike. In terms of doing that kind of basic solidarity work, we can be reasonably pleased with what we achieved, but it did not lead to any breakthrough in terms of building a revolutionary alternative. When you come up to 1989/90 and the whole question of the poll tax, I think the role we played there was again perfectly creditable, but it did not enable us to actually break through. I am sure you can identify weaknesses and mistakes in what we did in this period, but I do not think they were vital—that if only we had done A instead of B, everything would have been different. I just do not believe it.

EC: In the early 1990s, during what appeared to be a period of decline for the left in general, the SWP was actually able to grow to some extent. The SWP was able to engage with the anti-globalization or anti-capitalist movement, which culminated in the 1999 Seattle protests, but the politics of those movements tended to have an anarchist inflection if they had any clear political direction at all. To what extent did the SWP try to draw those movements towards Marxism? What did it mean to be a Marxist group engaging with those movements at that time?

IB: I am not sure how to answer that. Once again, I think the answer would have to be in terms of our publications. What we published in Socialist Review, International Socialism, and Socialist Worker was an attempt to give a Marxist orientation and to engage the people around us through those publications. We also had meetings. In the early years of this century, around the time of the Stop the War movement, we had local meetings called “Marxist forums,” once or twice a month, and we would take up issues relating to the current struggle and try and give a Marxist perspective on them. Whether we did it well enough, again, is open to discussion. I have heard all sorts of criticisms of what we did but I do not know of any alternative that would have made things dramatically different.

EC: Considering the parallel of the Stop the War coalition and the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC), what is the significance of the fact that the anti-Iraq war movement built its imagination on the memory of the anti-Vietnam war movement?

IB: You are quite right to see parallels between the VSC and Stop the War and to suggest that in some ways the latter drew on the example of the former. In both cases the original initiative came from the revolutionary left—IMG for the VSC, SWP for Stop the War. Both drew in very large numbers of people beyond the far-left milieu. Stop the War was, however, very much bigger. The biggest VSC demonstration was at best a hundred thousand; Stop the War mobilized at least one million, perhaps up to two million.

But it is also important to note one big difference. The VSC was a solidarity movement—Vietnam Solidarity. We were committed to the military and political victory of the NLF in Vietnam, and for a great many of those involved the NLF was seen as a socialist organization which would establish socialism—perhaps more of a Cuba-style than a Stalin-style socialism—in Vietnam. On the demonstrations there were frequent chants of “Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh!” Things were quite different with Stop the War. Most of those taking part had no doubt that Saddam Hussein was a brutal dictator. In 1991, at the time of the first Iraq war, there had been a small contingent, composed mainly of the remnants of orthodox Trotskyism, who had the slogan “We Back Iraq.” If they were still around in 2002 I did not even notice them. So, the arguments about the nature of the regime in Iraq were quite different from those that had taken place about Vietnam.

EC: As we have discussed, to some extent the problem remained the same, which was the issue of the development of a revolutionary alternative to the Labour Party. Coming out of the Stop the War Coalition there is an attempt to form an electoral alliance to the left of the Labour Party in Respect. You have written, looking back, that you were rather being used by George Galloway, but had thought that you could use him—that there was a who-whom dynamic at play.

IB: We kept on trying to build an alternative. We tried first with the Socialist Alliance. We tried at the beginning of the present century with the Stop the War movement and then with the launching of Respect. Now, Respect went horribly wrong. Whether there was some simple mistake or whether it was just not possible to launch an alternative, I still think it was worth having a try at launching what would be a fairly broad alternative to the Labour Party, for all sorts of reasons.

There was not any doubt that Galloway was using us. We understood that from the beginning. Galloway needed people on the ground. Galloway had got his own personality and I don’t think it should be forgotten how impressive Galloway can be. But in order to turn that into a political movement, which was what he wanted to do, he needed legs on the ground, he needed people knocking on doors and so on, and there was only one place he was going to get that: from the SWP.

I think we made tactical mistakes. The SWP leadership did not handle it terribly cleverly. I would not want to say that Galloway was just in it for personal aggrandizement, but there is certainly an element of personal vanity in Galloway. I do not know if the thing could have worked if we had understood that a bit earlier and tried to control him a bit earlier. But I think it was worth a try, given that there were no other alternatives readily on offer. It is not that there was some other way of building a mass revolutionary party that was easily on offer and which we disregarded—because nobody else did it! But the whole thing did fail, and it was a significant setback for us all. I’m sure did cause a certain amount of demoralization among Galloway’s supporters and among our members.

EC: It is partially for other reasons, and not long after that, that the SWP itself started to have a crisis.

IB: Yes.

EC: There are various splits that came out of the crisis of the SWP, including Counterfire and Revolutionary Socialism in the 21st Century (or rs21). Thinking back on the Tony Cliff’s organization and the entire IS tradition, who do you think has picked up the legacy of the SWP after the crisis?

IB: That is a big question and a difficult question. Counterfire had already split a little earlier. The two main groups that came out of the SWP split in 2013 were rs21 and the people around Salvage, which is mainly a magazine—I do not think they actually call themselves an organization. My personal position after the split was that I was not going to join any of the organizations that emerged. I should be clear that that was a personal decision, based on my age and my state of health among other factors.

I am very wary about pronouncing on the current state of the British left. Although I try and keep up with reading online and various print publications, and I see quite a few people, I do not get out; I have not been at a meeting or a demonstration for over a year. So, it would be very presumptuous of me to start commenting on the way that the various organizations on the left operate. That is my personal position. If I were to be asked to choose, I suppose I feel myself closer to the people in rs21 than anybody else, but that is not an exclusive choice. I still see and communicate with some people from the SWP. I still maintain fraternal relations with the SWP to the extent that it is possible. I used to speak at their events. I certainly would not want to pronounce the true successors of the SWP. I do not find that a very interesting question.

I think there were some very good things about the SWP, in terms of its analysis, the way it operated, the way it participated in campaigns, etc. I think there were also some bad things in that tradition. We made some very bad mistakes and we adopted some very bad habits, which I think caused us a lot of problems when the crisis erupted. I am not going to go into the 2013 crisis. I have said what I have to say about that. We are where we are. But I think some of those bad habits did manifest themselves in the crisis, which in a sense arose from the conduct or misconduct of one particular individual. But it did not have to develop the way it did.

Even if the 2013 crisis had not happened, there would have been big problems for the SWP with the whole Corbyn experience, which has shifted the balance of forces and has raised the question whether socialists should be in the Labour Party. A couple of years ago I would have said, “of course not.” And now, well, I personally am not a member of the Labour Party and there would be little point of me joining (because I would not be able to get to the meetings). But I understand why many people on the left have joined the Labour Party—and good luck to them! I certainly think any political dialogue that takes place over the next year or two has to include all those people who have joined the Labour Party; I think it has to include all those people who for whatever reason have decided not to, as well.

EC: Had the SWP not gone through a crisis in 2013, how would the Corbyn phenomenon have posed a significant problem?

IB: I was as surprised as anybody else on the left when the Corbyn phenomenon took off. When Corbyn first announced he was going to stand for the leadership, my reaction was that he should not, because he would just lose very badly and that would expose the weakness of the left even more. I was absurdly wrong, of course, but that was my position. I was then fairly convinced that the right wing would succeed in stabbing him in the back and removing him, and I also believed that the Labour Party would do very badly in the recent election. So, I have been wrong all down the line.

The problem was that when the Corbyn phenomenon took off, obviously you had to support it. It would have been ridiculous ultra-left sectarianism for any group on the left simply to come out with statements about how Corbyn is a reformist and not a revolutionary—which of course is true—or that Corbyn is in a very weak position, that Corbyn will be forced to water down his programme. You could have come out with a whole set of analyses, some of which would have been in formal terms perfectly correct, but you would have been ignoring the half a million people, give or take, who have joined the Labour Party. I am sure some of those are not terribly serious; nonetheless there is a real body of people there who have come to support Corbyn and I think that is genuine support. A lot of people have been genuinely radicalized. Nobody who is serious about developing the strength of the left can ignore that.

The problem is, if you are an organization like the SWP, what do you do? For quite a long time the SWP was saying perfectly correct things in support of Corbyn—and not very much else. Now it has become a bit more critical of Corbyn, but the danger is still this choice between either uncritically supporting Corbyn or making abstract criticisms of Corbyn’s position which are formally correct but do not actually get you anywhere. Simply pointing out that he is a reformist not a revolutionary, that the power of the state remains and so on: all of this is true and needs to be said in some form or another, but you need to find the form in which to say it.

An organization like the SWP can not dissolve. It is too big, it is too implanted, and its members are too well known. If the SWP announced it was winding up and calling on its members to join the Labour Party, the vast majority of them would not be allowed to join. So, you are left with a problem: how do you carry on as a political current, how do you maintain a publication? The SWP could not have adopted an entryist position, but on the other hand, the SWP has been pushed into the position of very largely taking a tailist position, simply going along with the Labour Party. I do not know what the alternative is.

I do not want that to come across as simply a blanket criticism of the SWP. I do not think it is the case that the SWP could have done something so much better, but they failed to understand something. I do not have a strategy for what the ideal revolutionary organization could and would have done in the face of Corbyn. It has posed a very serious problem for the SWP and for the whole of the left. The position of the Militant (or what used to be the Militant, the Socialist Party) is very similar. They are tying themselves in all sorts of knots about whether the nature of the Labour Party has changed.

Corbyn will not last forever and his successor almost certainly will not be as good as Corbyn. Corbyn is in a sense the other side of the Galloway coin. Galloway represented a good political position which was marred by his own weaknesses. Corbyn actually has enormous strengths as an individual. Corbyn has maintained a certain personal integrity after 30 odd years as a Labour MP. It is almost unbelievable. But that means the whole thing is balanced on Corbyn’s personal integrity. I do not see any similar personal capacity elsewhere—certainly not in Diane Abbott or John McDonnell. I do not see who would be Corbyn’s successor. And he is not quite my age, but he is pushing 70. So, there is a real problem as to what Corbyn can actually deliver. But, I have been disastrously wrong about Corbyn three times, so I can be wrong about Corbyn four times.

EC: You have discussed how we have seen greater barbarism than Rosa Luxemburg could have imagined, despite her having lived through the horrors of the First World War. Yet it seems harder than ever for us to make a clear diagnosis of our historical situation. Where do we stand in relation to Luxemburg's pronouncement of “socialism or barbarism” in light of present conditions?

IB: Within my lifetime there have been two points at which it was possible to envisage a transition to socialism. Of course, I do not have a detailed scenario—all revolutions are surprises. But in 1945 there was widespread demand for radical change in many parts of the world, which found expression in the development of “welfare state” reforms in Western Europe and the successful demand for colonial emancipation with the destruction of the European empires over the next 20-30 years. But the concern of the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., in their different ways, to impose their control over the world, stifled the potential. In 1968-75 the two superpowers seemed to be seriously weakened, with the U.S. facing defeat in Vietnam and major opposition at home with civil rights/black power, while the U.S.S.R. had Czechoslovakia. From France to Portugal (and then Poland), factory occupations seemed to be opening a new phase of workers’ control.

Compared with those two periods I do not see at present what a transition to socialism would look like. I am not saying it is impossible—just that I can not envisage it. What I can envisage, very clearly, is barbarism. What I think is impossible is the reformist illusion, that the world can just go on in pretty much the same way, being made a bit more humane, a bit more rational, a bit more eco-friendly. Within a couple of generations global warming will make large parts of the planet uninhabitable. There will be massive population movements, far greater than anything we have seen so far. The response, in the more fortunate parts of the globe, will be a rise of right-wing nationalism, intent above all on closing frontiers. Whether such movements will be “fascist” in the classic sense is secondary; they will certainly be very nasty and very repressive. In that situation, and with nuclear proliferation, accidental nuclear war becomes ever more likely. It seems to me that the only imaginable alternative would be a society that is radically different, in which cooperation replaces competition and in which there is a much greater degree of equality—something similar to what has traditionally been understood as socialism.

EC: Towards the end of his life, in the 1990s, one of the last books Tony Cliff worked on was Trotskyism After Trotsky. You write in your biography of Cliff that his concern was to be able to preserve and transmit the tradition of Marxism, a tradition that he had not only sought to build an organization around, but also sought to educate people in. Earlier you talked about how Cliff insisted that Marx’s writings and the writings of the Second International and Third International Marxists were not to be treated as scripture, but read critically. Cliff was someone who was not afraid of changing things in a certain way. But you write that there was an unchanging core of Marxism that he built his analysis on right the way through, one that perhaps he was trying to preserve in some form at the end of his life. What is that unchanging core of Marxism? What did that mean for Tony Cliff?

IB: If you had asked Cliff that question, he would probably have said: the emancipation of the working class is the task of the working class itself. That contains, firstly, the question of class: socialism will be achieved by the working-class. Of course, this leaves you with all sorts of questions. What is the working-class? The working-class has changed; it clearly is not the working-class that existed when I was a young man, let alone when Cliff was a young man. But the idea that there is a working-class, that society is divided into classes, that the institutions of society are determined by class divisions, and that the state, paraphrasing Lenin, is always the weapon of one class against the other—that would be the first part. Secondly, the task of the emancipation is the task of the working class itself—therefore rejecting what Cliff, using a word that Trotsky invented, called substitutionism. There is no force that can substitute itself for the working-class, whether it be the red army or a group of left MPs. Ultimately it has to be the working-class acting for itself. That implies organs of direct democracy. It implies soviets, workers councils, the working-class acting for itself—not acting through parties, states, armies, or whatever, that claim to be its special representatives. That is roughly how Cliff would have defined the unchanging core of Marxism and that is how I would define the unchanging core of Marxism as well.|P

[i] Additional reflections on the legacy of Tony Cliff in the pages of the Platypus Review can be found in James Heartfield, “The anti-political party: book review: Ian Birchall, Tony Cliff: A Marxist for His Time, (London: Bookmarks, 2011),” Platypus Review 55 (April 2013). Available online at: /2013/04/01/the-anti-political-party/. See also David Renton, “What is Cliffism worth? A response to James Heartfield,” Platypus Review 65 (April 2014). Available online at: https://platypus1917.org/2014/04/01/cliffism-worth-reply-james-heartfield/.

[ii] Michael Kidron, “International capitalism,” International Socialism 1, no. 20. (Spring 1965). Available online at: https://www.marxists.org/archive/kidron/works/1965/xx/intercap.htm.

[iii] Likewise, with Iraq – one could very easily argue that it was not in the interests of U.S. —or British—capitalism to involve itself in a long, expensive and unwinnable war in the Middle East. But they did so. Alex Callinicos’s 2003 book The New Mandarins of American Power offers the SWP analysis.