1989 and its significance for the Left

Gerd Bedszent, Patrick Köbele, and Stefan Bollinger

Platypus Review #77 | June 2015

On February 6, 2015 the Platypus Affiliated Society hosted a discussion at the Goethe-University in Frankfurt am Main on the subject of 1989 and its significance for the Left. The event’s speakers were Gerd Bedszent, a former member of the East German [GDR] opposition group Initiative für eine Vereinigte Linke [United Left] and presently of the Exit! group; Patrick Köbele, chairman of the German Communist Party; and Stefan Bollinger, author of 1989—Eine Abgebrochene Revolution (1999) and a member of Die Linke’s Historical Commission. The event was moderated by Markus Nieboditek of Platypus. What follows is an edited transcript of the translated discussion, an audio recording of which is available online at http://goo.gl/XIrT7H.

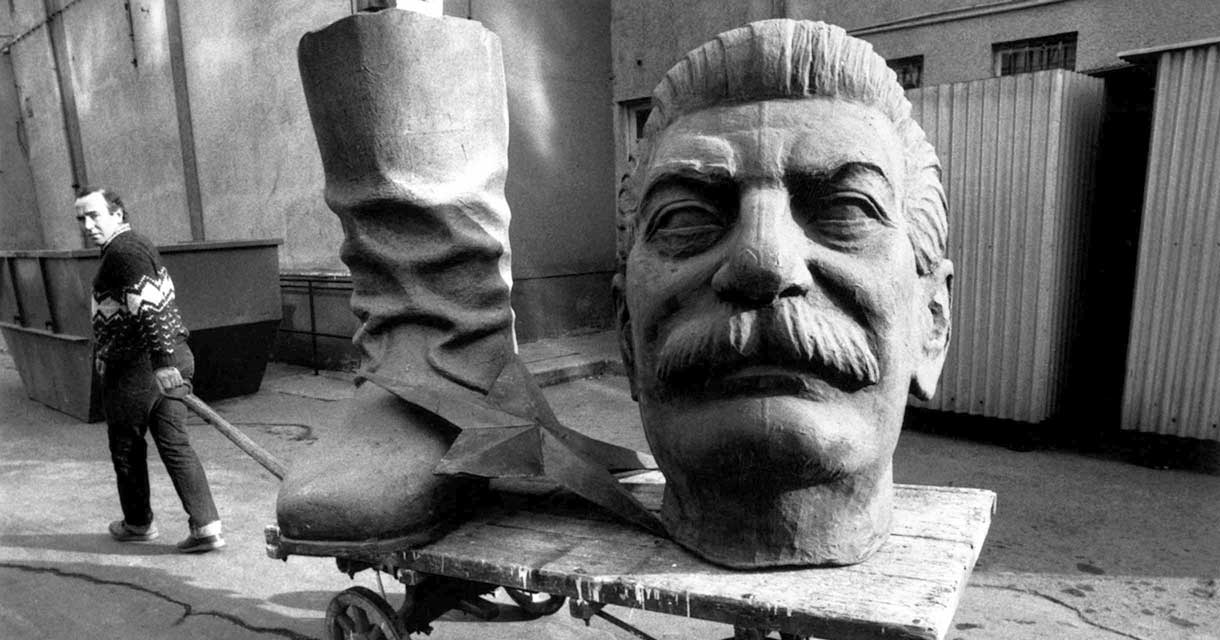

Demolished statue of Stalin in Budapest, 1990. © Ferdinando Scianna/Magnum

Opening Remarks

Gerd Bedszent: Although it thought it was, “actually existing socialism” was not more advanced than capitalism. In 1917 a bankrupt and extremely repressive regime in Russia was overthrown. Under Bolshevik leadership, Russia's backward and feudal society was industrialized and made literate in a few decades. A health care system was established and other progressive measures taken. There were similar modernizing regimes that tried as late developers to catch up to Western industrialized nations, though many did not pursue socialist aims.

The Soviet Union and its allies defined themselves as alternatives to capitalism. Nevertheless, the fundamental break with the system of bourgeois economy—the system of “capital, landed property, wage labor, the state, foreign trade and the world market”—was never achieved. Key capitalist forms were adopted unmodified in the “political economy of socialism.” The Russian revolutionary V. I. Lenin, a crucial influence for the early stages of socialism, praised the bureaucratic machinery of the German post office as a model for efficiency for a socialized national economy. The intended progress towards a classless society was in reality a regression to mercantilism characterized by the massive state intervention in the private sector. The alliance of actually existing socialist states in Eastern Europe could not catch up with the advanced industrial countries of the West any more than other late developers. By the 1970s this had become clear as the gap with the West steadily grew. This was when “actually existing socialism” failed.

That life in the Eastern European modernizing dictatorships, especially early on, did not correspond to what a lot of people had imagined life would be like in an anti-capitalist society certainly does not need to be emphasized here. The Bolsheviks found themselves excluded from the world market and denied access to Western credit. For ideological reasons they could not finance themselves by exploiting Third World countries, and, anyway, that was impractical. Consequently, the modernizing project could only achieve its aims at the expense of their own population, particularly the peasants. The use of forced labor in Siberian prison camps was the 20th century counterpart of the terror of early capitalist regimes that crammed expropriated rural populations mercilessly into gaols and workhouses to create the first modern proletariat. The liberal British bourgeoisie got rid of its surplus poor by deporting them, first to North America and then to Australia. Up to the 1950s French Guiana was a notorious penal colony and even today prison labor in the U.S. is economically significant and profitable.

Today the repressed memory of capitalism's earlier phase extends from Robespierre's Committee of Public Safety to the Caesarism of both Napoleons and from the authoritarian Wilhelmine state to the culmination of absolute inhumanity under Hitler. The crucial difference between the developed Western capitalist nations and their Eastern European stepchildren was that the latter could never get beyond the dictatorial beginnings of early modern times. The reasons for this were, however, primarily economic, not political. The pro-Western modernizing regimes that established themselves in the mid-20th century after decolonization brought to power the most obscure characters the catalog of whose human rights abuses could fill entire libraries.

So why did the Eastern European “socialism” fail economically? The most common causes instanced are inefficiency, overgrown bureaucracy, and the lack of incentives to work, but these are unconvincing. In modernizing dictatorships during their construction phase the home market is administratively shielded from the pressure of the world market so that industry can be developed, infrastructure built, and workers trained and disciplined. If the desired level of productivity is achieved, then government regulation can be curtailed and the national economy reintegrated with the world market. The problem is that each newcomer has to achieve more capital to reach the necessary level. In the case of Eastern Europe, the Western lead could not be overcome. The home market had to be shielded from foreign competition and export products heavily subsidized. Ultimately, the economy stagnated. The induced disproportion between import and export prices threw the Eastern European economies into a debt crisis. They depended on Western credits and thus became vulnerable to political blackmail. Professor George Fuelberth, surely no anti-communist, recently noted in the daily Junge Welt that the Soviet Union and its allies represented a project to catch up with the industrialized world. But they lacked sufficient dynamism and were inevitably destroyed by capitalism. But the advanced capitalist countries were themselves struck by crisis in the 1970s. The prevailing Keynesianism, economic growth based on state indebtedness, came up against its limits. The increase in tax revenues from economic growth was insufficient, so state indebtedness grew. The transition to neoliberal ideology was a logical solution. Forcing deregulation, the state's retreat from the economy, the dismantling of governmental infrastructure, and austerity programs not only led to the impoverishment of growing sections of the population, but also, with the help of the World Bank and the IMF, created massive poverty in the Global South. Today this has reached apocalyptic proportions. In 1991 Robert Kurz described the Eastern bloc nations caving in to their Western creditors as “socially and economically, theoretically and practically, capitulation on a massive scale.”

The social collapse of Eastern European regimes was thus foreordained. It did not matter if the free elections after 1989 were won by conservatives, liberals, or ex-communists (who had since become social democrats). The room for maneuver of these regimes was almost nonexistent. Economic stagnation had created a generation of economic functionaries that searched for and eventually found their salvation in the implementation of neoliberalism. The former electrician and union leader Lech Walesa who had already accepted massive wage cuts in the April 1989 negotiations with the Polish nomenklatura now turned neoliberal. In the Soviet Union the economist Vitali Nasjul suggested early on that the restructuring of the Soviet economy should be modeled on that of the Pinochet regime in Chile in the 1970s. After former Moscow party leader Boris Yeltsin seized power in August 1991, he undertook economic restructuring on Russian territory. When the Russian parliament put up opposition to the brutality of neoliberal economic reforms and to the criminal privatizations, Yeltsin allowed his troops to fire on the parliament building. The extension of social austerity policies was thereafter no longer impeded.

Neoliberal reform in Eastern Europe could only end in disaster. In Russia, for example, industrial production in 2000 had shrunk by 57% of what it had been in 1990. In the Ukraine in the 1990s the gross national product fell to 40% and agricultural production fell to one half of what it had been in 1989. In Poland industrial production dropped by a quarter in 1990 alone, whereas in Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria and Romania the same took place the following year. Hungary lost one-fifth of its industrial capacity in 1992. Altogether, industrial production in the countries of Eastern Europe sank between 40% and 70% from 1990 to 1993. In Bulgaria employment shrank in the 1990s by 54%, in Romania by 46%, in the Czech Republic and Slovakia by 39%, in Hungary by 35%, and in Poland by 16%. Even in the territory of what had been East Germany (formerly the showcase for Eastern European socialism), industrial capacity shrank by approximately 70%. The agricultural workers’ cooperatives survived, but between 1990 and 2000 they lost roughly 90% of their employees. Most East German cities have lost a third of their population since 1990. The “flourishing landscapes” Helmut Kohl promised in 1990 certainly came to be, only they are practically devoid of people.

What comes after the neoliberal disaster? Neither a return to a debt-financed welfare state nor to a modernizing dictatorship is a viable option. The rise of market radicalism was itself a reaction to the failure of Keynesianism. From the ashes of failed modernization projects no new beginning is possible under capitalism. The crisis constantly recurs and there is no solution in sight on the basis of the present system, nor is one likely to appear. Among the rejected and socially vulnerable, desperation rages, accompanied by periodic outbreaks of nationalism, racism, and religious delusion. There is a steady disintegration of social cohesion and an increase in struggle along national or religious lines. The installation by Western elites of a state-terrorist end-times étatisme might slow down these trends, but it cannot stop them.

It is not news that for the Left 1989 was a disaster. It had either oriented itself uncritically towards the Eastern European modernizing dictatorships or it simply lumped them all together in order to dismiss them en bloc. The Left has mostly refused to theoretically work through the economic changes of the most recent decades. Certainly it is not easy to admit to oneself that the main enemy, capitalism, is now dismantling itself and, in the process, dragging all of humanity down into the abyss.

Now I’m not trying to make the case for standing by with our hands in our pockets as capitalism collapses. Against the barbaric imperative of Western state-terrorism and the onrushing wave of chaos and social collapse, resistance is certainly called for. But the goal of the Left must be a society of solidarity, a society free from either the silent constraints of capitalism or repressive dictatorships. How to build such a society, I cannot say. One thing needs to be clearly stated, however. The laws of capitalist commodity production are not laws of nature. In principle they can be abolished. The alternative, which is certainly possible, is a fall into barbarism.

Patrick Köbele: 1989 was a defeat for humanity as a whole. Imperialism has now burst all bonds, so that the contradictions within it now threaten war and global destruction. Since 1989 a new era of imperialist wars has started, such as the present war in the Ukraine. There the objective is the containment of Russia by US-and-EU imperialism, which brings with it the danger of escalation. It is not only peace that 1989 threatened but also the danger of renewed neo-colonial oppression for large segments of humanity. Despite its weaknesses and ultimate failure, “actually existing socialism” nevertheless laid the foundation for liberating many nations from the colonial yoke. That has now been reversed.

From 1981 through the mid-80s I worked for Daimler-Benz. I apprenticed there and was the representative for the younger personnel. This was the time of the Metalworkers’ Union’s big struggle for the 35 hour week. At that time we felt that in the Federal Republic there was almost an even balance of power between capital and labor. Everyone, even the social democratic unionists, understood that the GDR was our invisible partner at the bargaining table. The very existence of “actually existing socialism” bolstered the position of workers in the capitalist countries. So, it is not that in 1989 imperialism came back. It was a constant presence, but the existence of “actually existing socialism” forced it essentially—with some notable exceptions—to deal with its inner contradictions without war and violence. It created a sort of farce of nonviolence, conjuring thereby the illusion for communists that imperialism had been rendered peaceful. Imperialism can never become peaceful, however. It can only be forced by a countervailing power to abstain for a time from violence.

Regarding the effect 1989 had on the international left, it created huge problems for communists like myself who identified with “actually existing socialism.” But it is remarkable that it led to any greater crisis for the reformists who seemed so strongly entrenched in the Federal Republic, above all in organized workers movement. When the prospect of transcending capitalism is lost it necessarily leads to a politics accepting of constraints. In this corporatist country, this means the disarmament of the workers movement and of proletarian internationalism. This creates in turn a very dangerous basis for further development, because tied up with the notion of social partnership is the risk that the workers movement will allow itself to be used to further ruling class interests, especially in the international arena. We can already see sections of the workers movement identifying with the rulers rather than the European periphery.

To ask whether the Revolution of 1989 was initiated by the Left or the right is to presume that what occurred was somehow intended, whereas in fact it occurred because of rising but unfocused dissatisfaction. Of course, the dissatisfaction itself was justified. The problem is (and we experienced it with all the “color revolutions”) that imperialist forces managed to channel popular discontent toward removal of regimes that were either anti-imperialist or uncooperative with imperialism, i.e. a counter-revolutionary process to undermine “actually existing socialism.” Not all individuals acted intentionally toward this end, but such was the result of their actions. I can recall clearly on the 40th anniversary of the GDR I was standing on the VIP stand. At that point it was still possible to have high hopes and to still regard the GDR as a socialist state. The illusions I had about this became clear to me that same evening. I was in the Palace of the Republic. When Gorbachev came in, everyone rushed to shake his hand. Although I was not conscious of it then, I am glad that I did not rush over. Gorbachev was nothing but a traitor. Of course, the question then is, how did a traitor come to lead the Communist Party of the Soviet Union? That is still a question that requires investigation. The Party played a big role in the shattering of “actually existing socialism.” As it lost its vanguard character, it paved the way to defeat.

So, what was “actually existing socialism”? From my perspective, it was socialism, but in the end it proved too weak. Otherwise, it would not have failed. After all, one cannot simply blame imperialism for socialism’s collapse. That weak socialism, during the course of its existence, contributed to the course of human development. It did so with regards to peace, liberation of the colonies, and the shifting of power in favor of the working class in the capitalist countries. I can only say that I look forward to a strong socialism. I do not regret even today that when I was politically active I stood on the side of “actually existing socialism.” Of course, we in the German Communist Party made mistakes just as a boxer makes mistakes when swinging wildly. We used euphemisms to describe negative aspects of “actually existing socialism.” But that does not change the fact that German communists could stand on no other side. We have to assume such solidarity as a position from which to analyze the mistakes that were made. The Party failed to create a different system of value, so the struggle with capitalism was waged on ground where capitalism is always better, consumerism. Surely there were many reasons why we lost the initiative with the masses. Still, I am proud that I stood, and still stand, on the side of “actually existing socialism.”

Stefan Bollinger: I want to focus on the upheaval in the GDR and to try to propose some ideas in the form of a few theses. First: As a historian, I naturally look at the calendar. Today is February 6th. 25 years ago the ministers in Bonn still had to work hard. On February 7th, a cabinet meeting took place in which it was decided that the Federal government would establish a cabinet committee on German Unity. The period of long-term observation of and preparation for the massive exercise of influence on the society of the GDR was completed. The phase that began, at the latest by November 8th, with Kohl's statement of clarification of government policy, which was followed by the 10-point plan. With his visit to Dresden it was put into practice. The solution was elegant enough: an economic, even a monetary union. This directly affected the mood in the GDR. Henceforth, the independent development of the GDR's last year, which had been connected with a democratic upsurge with round tables and grassroots democratic activism, was taken under the aegis of the Federal Republic.

Second: One must also note another process then taking place, one that made the Federal German decision possible in the first place. On January 26, 1990 in the Soviet Politburo a narrow steering committee decided how the Soviet Union would react to what was happening in Germany: We cannot support the maintenance of the GDR. This was a consequence of the agreement reached a month earlier in Malta with the United States. Hans Modrow, at the time Prime Minister of the GDR, was informed on the 30th that he now had the dubious task of flying back to Germany with a program called “Germany United Fatherland” and to commit his coalition government to this. The only ones to refuse were the comrades of the United Left. The Soviet Union then faced its own internal crisis and that in Eastern Europe. It decided for itself as a great power. A great power does not have friends only interests, an old adage that also seems to apply even to people with red party membership cards. And according to this principle, the question was decided. They hoped for the best possible terms, for Western credits to set economic reforms in motion. These took a very different direction from those promised five years earlier.

Third: Any discussion of the question of “actually existing socialism” and the GDR has to take the international peculiarity of the inter-German relationship into account. That “actually existing socialism” failed is certainly—one must constantly emphasize it—due to its own mistakes. Lenin, of course, was right: The task of “actually existing socialism” was twofold. In the first place, it had to struggle between systems and that meant accumulating the economic and military means to carry on the struggle, even as it developed the country, in order to create the conditions for its own population to recognize socialism and its achievements as its own and want to defend them. We did benefit from it but the will to defend it was lacking at a certain point. The rude awakening came a bit later.

Fourth: The futuristic state failed at the point when it could not keep its democratic and emancipatory promises. This, of course, was conditioned by the old society and by limited resources. One also has to remember that “actually existing socialism” emerged as the result of the wars triggered by capitalism that made the revolution possible. And though there was a national communist movement that supported the process, still in most countries they needed the support of Soviet and occasionally Chinese guns (and later nuclear weapons) to retain power, because they were often minorities. These general conditions influenced the modality of how “actually existing socialism” was built and came to be structured. Its massive democratic deficits can largely be explained, though not justified, by these general conditions. Socialism without democracy is not real socialism. Still, historical conditions must be taken into account and these included a merciless struggle between systems, a struggle that varied in the forms it took but which contained from the beginning the danger of nuclear annihilation. "Actually existing socialism" was not developed on the basis of its own values. Instead, most of the basic needs of this society were the needs, requirements, expectations, and consumer goods that were realized in the most developed countries. Perhaps this was not true for the whole society, but the scale was set in the West.

Fifth: It must be asked which GDR and which “actually existing socialism” are we talking about? The labels “totalitarianism” and “illegitimacy” do not help. This only devalues it and aligns it with Fascism. Still, the question of which “socialism” we are talking about is extremely complex. After the war, both East and West attempted to address locally the situation after the downfall of the Nazi regime on the basis of anti-fascism and the spontaneous organization of workers parties. This quickly got into the cross hairs of all the occupying powers and all the established parties, even the Communists. So much independence was not desired. Or, do we mean the time in which “actually existing socialism” was established? In the East, a growing minority played a crucial role in building socialism. These were people won over by the defeat of fascism: They came from Soviet POW camps, from Nazi concentration camps, or from exile. They were communists, socialists, democrats, and intellectuals. But their powers were increasingly confronted by the Stalinization of that society and party. Or, are we talking about the time of the reforms of the 1960s in which the goal was to build up material prosperity with the inclusion of all social classes and strata in the new economic system? Such reforms posed the question of how such an economic restructuring could work without democratizing existing political structures. As is well known, such an approach was crushed in Prague with tanks, but also in the GDR such approaches were scotched pretty quickly. Or are we talking about the “actually existing socialism” of the following years which wanted to create pragmatic and technocratic prosperity to maintain loyalty and to create a stable future but which actually ended in stagnation? Or are we talking about the very end, that most thrilling and exciting last year of the GDR when reforms and revolutions were attempted by citizens’ movements and reformists within the governing party. They wanted a different, more democratic-socialist GDR and strove for an anti-Stalinist revolution to achieve it. At that time there was a greater clarity about what one did not want than about what one did. These attempts were not solely directed against a Stalinism of open repression and terror, which surely got milder in the 1980s (though it still operated within the old structures). In my opinion that is where “actually existing socialism” met its limits. It was structured as a centralized, bureaucratically administered socialism with an all-powerful and, worse, all-knowing Communist Party where in the end everything even down to the supply of imported jeans was determined in the head office of an overly centralized planned economic system. It worked from top to bottom rather than bottom to top. Then there was the security apparatus that saw enemies everywhere, even amongst those trying to improve society. Finally, the crisis management mechanism relied on the threat of violence. All that has to be kept in mind.

Defaced Lenin and Stalin, Parliament Square, Vilnius, 1991. © Chris Steele-Perkins/Magnum

Q&A

If socialism and commodity production are contradictory as Gerd Bedszent claims, how then should one assess the citizens’ movements of 1989? Was it a “counterrevolution” as Patrick Köbele puts it? Or would calling it “anti-Stalinist,” as Stefan Bollinger does, be appropriate?

GB: The active opposition to the GDR in the early 1980s developed due to the influence of the West German Greens. Initially, the GDR leadership was on good terms with the Greens and permitted events for educational purposes, but later entry bans were imposed. The first truly oppositional movement, the Initiative for Peace and Human Rights, emerged around 1985. Some of its splinters developed into mass movements only to disappear just as quickly. In 1990, it merged with the Greens. The second opposition group was the Initiative for a United Left. This was the radical left wing of the GDR citizens’ movement. It was the only group open to critical persons inside the SED, which was why the others refused to cooperate with it.

I was an SED member and studied economics in the GDR. In the fall of 1989 my professors suddenly started saying the opposite of what they had been saying. When, on top of that, a Party secretary told me to attend a speech delivered by Helmut Kohl, I decided to join the United Left. Their goal was to find an alternative economy similar to what had been worked on in Green circles. From the vantage of today, I would not deem this to have been successful. They were muddled ideas that largely recycled worn-out state socialist ideas. We wanted to cling to socialism and to improve it, even if it meant fighting a losing battle. I do not regret this and would do it again.

PK: There were good reasons for championing radical change in the GDR. Socialism should set free the masses’ creativity and this requires vigorous debate. It is a shame that this did not take place despite our many protests. The transformation of “actually existing socialism” that we espoused put us in a difficult position. But there were also openly counterrevolutionary forces: the Lutheran Church and forces controlled and financed by the West. Meanwhile, the SED ideologically disarmed itself. So, various factors reacted with each other: the discontent of the population, the petrified structures of the SED, the economic question, the superiority of imperialism, and, last but not least, the betrayal of the USSR which effectively sold out the GDR. That was why I preferred the United Left to the SED/PDS. They opened the gate for social democracy. Kohl seized upon the ideological collapse to entice the masses with the deutschmark and “shop window capitalism.” People tended to lose sight of the GDR's achievements. It is difficult to convince people that even if they do not get a stereo system, at least they are not exploiting the Third World and do not have to worry about unemployment.

SB: The expression “anti-Stalinist revolution” implies the possibility of overcoming all structural deficits. It has been a perennial issue throughout the history of “actually existing socialism.” It manifested itself historically in moments of crisis—in 1921, 1953, 1956, 1968, and 1980-1. Every time it takes the form of justified discontent amongst significant sections of the population, including the working class. Usually the questions involved a desire for consumer goods, or the management of the labor process, or a desire for democratic participation.

Discontents were instrumentalized by both sides in the Cold War. The ruling authorities in the East treated the discontent as a threat, while the West, of course, hoped for a “fifth column” in the struggle against Communism. The pattern repeated itself in 1989. Some of the more intelligent reformers were aware of this dynamic, but, still, dealing with it in practice proved difficult. Both the citizens’ movement and the SED reformers wanted a more humane socialism. Only a few demanded the overthrow of the regime. That was the exception then, even if now many of those—particularly those in the citizens’ movement—no longer wish to remember this pro-socialist phase. And, necessary political changes were initiated at that time. The party leadership had disappeared and the General Secretary was ill. In such circumstances the people simply called for a dialogue: “You ought to have open discussions.” They were essentially asking for the same thing that was previously discussed in the 1987 joint paper drafted by West Germany’s SPD and the East’s ruling SED party to enable a reduction of hostilities between the two countries and the opening of discussion about systemic issues. This attempt to do something differently prompted many discussions and grassroots democratic activities. It forced new elections of company managers and shook up party structures. It brought new people and a new spirit into the party leadership. But, in the end, no one led this revolution. The citizens’ movement reckoned that the seizure of power was not its job and the SED reformers proved to be too weak to reorganize the party.

The historic break manifests itself on two dates: November 4 and 9, 1989. On November 4, the movement for reform reached its peak at the Alexanderplatz with 500,000 people publicly calling for change and party functionaries actually talking to the people. Anyone paying close attention to these events sensed the difficulty they posed for the old SED functionaries. Five days later—I call it a “silent coup d'état”—the SED leadership decided to open the borders. They were unaware of the repercussions this would have. Even the border guards—including their Western counterparts—were not informed. While they discussed revising the rules for travel, people laughed at them. The leadership wanted to find an answer to this problem. Above all, they wanted to keep people off the streets. Also, they thought that when people see how bad it is in the West, they will gladly return to the GDR and desist from protests. On November 9, the revolutionary phase comes to an end and the West takes the GDR under its wing.

The development of the revolutionary and grassroots democratic movement led to two important events: First, a Round Table in early December that was supposed to give the GDR a new political foundation. Secondly, a draft constitution that was proposed on April 6, 1990, when it was already too late. I still think that this draft serves as a model for left and alternative forces of a legal system incorporating elements of direct democracy and allowing for participation in economic decision-making. At this point even though history had passed by what was outlined in the draft, it should still be of interest to the Left. There is something lasting we can still learn from this process.

Trotsky suggested that it was precisely the bureaucratization of the Party that threatened to squander the achievements of the working class. And, indeed, in 1968 the Stalinist parties of the West tried to undermine the student riots and the strikes. Should not, then, the collapse of the GDR be understood in terms of the failure of the Left?

PK: The collapse of the GDR was not a retrospective confirmation of Trotskyism. There was no possibility of a “rollout” of the October Revolution on a global scale. The hope was in the German Revolution but it was smashed by the Social Democrats. What should the Bolsheviks have done? They could have said: “We cling to our former hope and keep going.” Historically, this was not an option. Besides, Trotskyism cannot explain the achievements on a global scale of a supposedly degenerated socialism. This becomes clear when considering in hindsight the counterrevolution that took place 25 years ago.

According to Marx and Lenin the state arises out of a conflict of class interests and should wither away in the period of the “dictatorship of the proletariat.” But this is in direct contradiction to what happened in Eastern Europe. Does the thesis of Marx and Engels need to be revised or are we dealing with a continuation, even strengthening, of these contradictions?

PK: Clearly Marx, Engels, and Lenin hoped for a shorter period of revolution. They assumed that the necessity of the state under socialism would be of shorter duration. But when attempting socialism in a hostile environment, the state necessarily has a defensive function. One should have no illusions: Imperialism will take every opportunity to destroy socialism. It will seek to exploit internal conflicts for the purpose of fostering counterrevolution. Socialism needs to defend itself against this, including intelligence services. However, it is crucial not to forget that socialism is still an oppressive societal model. There is a ruling class, namely the working class, and the bourgeoisie, which, though deprived of power, is not yet fully eliminated. One cannot stop with the expropriation of the means of production since there remain vestiges of capitalism in the ways people think and act. There is a danger that they can ally with capitalism and imperialism. To think of socialism the way Marx and Engels described communism is an illusion that leads to anarchist positions that I do not subscribe to. Our Chinese comrades described this as a problem of three generations. The first brought about the revolution and knows what's what. The second had experienced capitalism, but the third grew up in a socialist society where we encounter problems of consciousness. For the workers in Cuba “freedom” means opportunities for consumption.

SB: There were constant attempts to change people's system of values, particularly in the early years, and this worked well even if such changes did not extend to the whole society. Still, in a complex situation, enthusiasm and readiness to make sacrifices spurred people to action in the Eastern Bloc, including the GDR. Naturally, it was difficult to carry that spirit on to the next generation. By the 1970s there was a break among the younger generation. It derived from a weakening of the stereotype of the enemy but also from a heightened sense of the risks of military confrontation. Also, the younger generation preferred the consumer products and culture of the West. This was important in 1989.

The greatest difficulty though was in creating conditions in which citizens could exercise democratic rights. There were times when this was demanded by critical intellectuals and it was conceded by the leadership, but never permanently. An evolved form of such a reformist approach might have developed in Czechoslovakia. Of course, this might not necessarily have entailed the strengthening of socialism. At any event, Soviet tanks cut the experiment short.

In theory, the working class played the leading role in society, but the Party leadership thought: “Well, the working class is not ready yet. Therefore, we need to act on their behalf to help bring forward the best cadres from this class so that eventually they can take on this role.” Certain conflicts occurred since the Party did not always accurately read the mood of the working class. That is what happened in the GDR in 1953. The conclusions the SED drew ran something like this: “We have full control over economic and social policies and we cannot allow the working class to revolt against its own state.” This meant that prices could not be raised and you had to be extremely careful when tweaking the work norms. In the GDR we stuck with this until 1989 even though it did not contribute to economic efficiency. There were two perspectives at the time: One was the market-oriented one of the economic functionaries, the other looked at it from the point of view of the working class even if this class did not hold power directly. And if the leadership did not concede the working class perspective then one had to organize for free spaces. The workers fought for their autonomous spaces that reduced work pressure lower than it would have been if the market-oriented functionaries had had their way. In this way the workers achieved a degree of emancipation, but still this experience did not prepare them to lead society. In Marx's view there was supposed to be a brief transitional phase. That should have happened many times in 70 years but it never did.

GB: I began by explaining that the “socialist economy” was based both on commodity production and state planning. Socialism did not invent the public economy, it borrowed it from capitalism. It had existed during the wartime economy of both world wars, during which the state had stipulated the production of enterprises and set prices and wages. The capitalists went along with this because they expected large profits at the end of the war. By contrast, “actually existing socialism” indefinitely prolonged the wartime economy. It eliminated domestic competition by determining wages and prices. Almost the entire economy was regulated by the state, leaving only small vestiges to the private sector. Furthermore, the state monopolized foreign trade. But, despite this, it was unable to free itself from the global economy, because the socialist state was itself integrated into this global economy and acted as a giant enterprise. Capitalist laws and mechanisms applied to it.

There was a kind of social legislation, but precisely because of this the socialist state was economically disadvantaged with regards to those states that did not have such excellent social legislation. It was a competition between different social systems. It was only a matter of time before capitalist laws imposed themselves. In this respect, the debts of the GDR are not so insignificant as they might seem. If one did not pay them, one would not be creditworthy and would be cut off from commercial relations.

Nowadays the experience of the GDR is looked down on. Is that a correct evaluation? What is the political heritage of the GDR and the Soviet Union? Will not all future attempts to seize power and establish a planned economy be discredited because of this historical experience? What does this history mean for us today?

PK: In this much needed discussion about the GDR we have to be careful we do not end up speaking like the class enemy. The nonsense that it was an illegitimate state disarms the working class. We need to examine when and why the masses of the GDR and the Soviet Union strongly identified with the state and socialism and why later this ceased to be the case. We should not make the mistake of discussing only the failures of socialism and not those of capitalism. We also need to demand a planned economy and the abolition of private property.

GB: It is difficult to generalize about the GDR because it underwent profound changes over the course of decades. If one is talking about the last phase in the 1980s, then this indeed marks a very depressing phase. Not because of political repression, which was, despite what is portrayed nowadays, only directed at the political underground and never affected more than a few hundred people.

Everyone knew that the economy was in a miserable state and that nothing could be done. Yet everyone claimed the opposite. In newspapers and on the radio the opposite was constantly asserted. If you went to Party secretaries and complained, they responded that you did not have the right political attitude. The late GDR was a society in which there was a fantastic amount of lying. In my work, I was forced to give false reports even though everyone knew that the numbers were fake. So, for me, 1989 was a liberation even though ultimately it unleashed a catastrophe.

SB: Yes, it was a time of stagnation and apathy but 1985 marked the beginning of a period of many discussions, including within the Party. Gorbachev's reform initiatives were closely followed, including when these failed in 1987-88 and turmoil ensued.

If the Left wants to pursue politics ever again, we need to come to grips with the history of “actually existing socialism.” We cannot simply draw a line and hope that we are relieved of the burden of the past. We have to examine these experiences critically, including the form of planned economy and the Party, particularly a party that suppresses dissent. That was wrong then and it will be wrong in the future. Every generation needs to tackle these questions. This means having an understanding of the complexity of the history of “actually existing socialism,” to deal with its injustice and its crimes but also to recognize its accomplishments. One needs to address the whole in its contradictory character. |P