The dialectic of the core and the periphery: The surge of the Japanese Communist Party during the high-speed economic growth period, and limitations in its development

Morita Seiya

Platypus Review 176 | May 2025

THE JAPANESE COMMUNIST PARTY (JCP), founded in 1922, is in its 103rd year in 2025. In 2023, the Party published the party history book 100 Years of the Japanese Communist Party to commemorate its centenary.[1] However, it is a self-congratulatory book written by the JCP itself and does not analyze the history of the rise and fall of the Party in a social and class-based context.[2]

In this piece, I will take on that challenge. But the history of the JCP is extremely complex and rich, and it is impossible to discuss its whole picture in this short essay, so I will choose to focus on one topic here: the JCP’s big surge during Japan’s high-speed economic growth period, and limitations in its development.

※ ※ ※

The postwar history of the JCP begins with the unconditional surrender of Imperial Japan in August 1945 and the release of non-converted Communist leaders (including Miyamoto Kenji, Tokuda Kyūichi, and Shiga Yoshio) from prisons by the order of the Allied occupation General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP)[3] in October of the same year. In January of the following year, Nosaka Sanzō, who had been in exile in China, returned to Japan with hundreds of other Japanese communists, and the organizational activities of the JCP resumed in earnest.

Due to the fact that the majority of progressive intellectuals, including many Marxists, supported the imperialist wars and the imperial state from the mid-1930s, the political authority of the handful of Communist political prisoners who declined their conversion after the war rose dramatically. In addition, the political authority of Stalin’s Soviet Union, which crushed Nazi Germany in World War II, also worked greatly in the Communist Party’s favor. At first, the SCAP set the stage for the explosive growth of the postwar Leftist movement by releasing political prisoners and legalizing the JCP and labor unions. However, prompted by fears of the Left-wing movement’s too rapid development and the start of the international Cold War, the SCAP began to take a so-called “reverse course” and attacked the Communist Party and militant labor-union movement fiercely through the Red Purge[4] and various conspiracies.

Alongside this, Japanese monopoly capital succeeded in undermining militant labor movements by creating collaborationist unions within their companies. Most of the JCP members were laid off through the Red Purge. On the other hand, in the public sector, the majority of labor unions are affiliated with the Japan Socialist Party (JSP),[5] and so members of the Communist Party were driven into an overwhelming minority.

Despite such intensive suppression, the JCP itself was not destroyed, unlike before the war, even if the Party and the various movements under its influence were to a considerable extent marginalized. However, ironically, this marginalization actually created an opportunity to form the material foundations for its surge during the period of high growth in Japan.

We can see a similar phenomenon in the history of biological evolution. In a given era, the species that best adapt to the dominant environmental conditions of that time flourish and dominate the most advantageous and widest spaces. On the other hand, some species that lose this inter-species competition are driven to the periphery and undergo unique evolutionary changes in order to adapt to more disadvantageous and harsher environments. Later, when the dominant environmental conditions change drastically due to some major events, the species that were best adapted to the old environmental conditions of the past are unable to adapt to the new environment and become extinct, while the peripheral species that have survived in more unfavorable and harsh environments are able to adapt more rapidly to the new more favorable (for that species) environment, and go on to flourish in the next era.

Something like this also happened in the JCP’s history during the high-speed economic growth period. Soon after the end of the Pacific Theater of World War II, the labor unions of major private companies became collaborationist enterprise unions, and their core activists became anti-communist. In addition, the labor unions of large public enterprises such as Japan National Railways, the Japan Post, and Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Public Corporation were mainly controlled by members of the JSP, so the JCP was forced to look for other bases for organizing. Their main targets were young, unorganized workers, schoolteachers, local and lower-level civil servants, university students, the small urban self-employed people, workers at small factories, housewives in newly developed residential areas, and employees of hospitals, clinics, and consumer cooperatives organized by the JCP members in urban areas.

These various classes and strata grew in number to an ever-increasing extent during the period of rapid economic growth. They were also plagued by many contradictions (excessive exploitation, low wages, public pollution, rising rents, urban alienation and poverty) due to Japan’s too rapid economic growth and the conservative political regime. And new pacifist, democratic, and cultural desires were extremely strong among them. Under the political regime of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)[6] that depended on U.S. imperialism, the JCP actively worked on issues such as the campaign against nuclear weapons and U.S. military bases, the defense and realization of the post-war democratic Constitution, the anti-Vietnam War movement, and the improvement of the status of workers and farmers.

The mass organizations that the JCP actively organized included many cultural organizations such as the Labour Music Association (Rō-on) and workers’ theater groups. In particular, Rō-on grew to become a large organization with 500,000 members at one point. The most important mass organization affiliated with the JCP was the Democratic Youth League (Minsei),[7] a youth organization open to members aged 15–30 that was also active in education, culture, recreation, as well as in political activities. These organizations were in response to the cultural needs and desire for social interaction of the huge numbers of young male and female workers who had moved from rural areas to the cities. These organizations and their spheres of activity provided them with a new sense of community — one that was more open, sex-equal, and democratic, replacing the patriarchal, backward, and closed communities to which they had belonged in their villages.

Also, the JCP placed emphasis on neighborhood activities in newly developed urban housing complexes (danchi), actively addressing the everyday-life demands of young couples with young children working in small and medium-sized companies as well as in local governments. These activities encouraged mutual aid and political consciousness-raising within communities under Japan’s postwar low-welfare system, and led to a rapid increase in the number of local JCP legislators.

In contrast to the fact that the core of the labor movement in Western social democratic or communist parties was large-scale labor unions in private and public corporations, the JCP was largely excluded from these cores, and marginalized both socially and politically. Therefore, it sought out different political and class bases, evolving into an organizational form that was suited to these new bases, and this became a major advantage during the period of rapid economic growth. We can name this phenomenon a “dialectic of the core and the periphery.” The dual organizational expansion policy of the JCP under the leadership of Miyamoto Kenji, namely the expansion of the Party itself and the expansion of its affiliated mass organizations, was a development strategy that it had cultivated in order to expand and maintain its influence without relying on large labor unions in the private and public sectors.

Therefore, even though, during Japan’s high-speed economic growth, workers and labor unions of large private corporations were increasingly incorporated into the harsh control of corporate management, the JCP was able to continually expand its political and organizational influence, because it found a rich material and political foundations in the periphery and evolved into its organizational form suitable for organizing these elements.

Moreover, this was also the key to why the Party was able to maintain its organizational strength for a long time, even during the period of low growth from the mid-1970s onward and the wave of neoliberalism that swept in from the mid-80s, which led to the decline of labor movements not only in the private sector but also in the public sector. While the JSP crumbled under attacks aimed at dismantling public sector labor movements — such as the destruction of the National Railway Workers’ Union (Kokurō) following the privatization and break-up of the Japanese National Railways (Kokutetsu) in the mid-80s — rapidly shifting to the Right and ultimately declining, the JCP was able to maintain its strong organization by relying on its own peripheral social bases.

※ ※ ※

If we compare this policy of the JCP with that of the New Left, which developed explosively in the 1960s and early 70s and then rapidly declined, its relatively different characteristics will become more apparent.

The New Left grew by excessively adapting to the unique environment of universities, which had been opened up to only a handful of wealthy people during the prewar era, but which exploded in student numbers during the postwar era as universities became democratized. Since the New Left’s line was extremely suitable for the period when universities were politically radicalizing, its various sects temporarily gained organizational successes that surpassed those of the JCP at Japan’s major universities.

However, the New Left’s strategy soon came to a dead end as the students became increasingly conservative from the late 1970s. The militant and violent style of activity of the New Left was only able to attract a small number of young people who were extremely rebellious towards society. As students became more conservative, the number of such people rapidly dwindled. Universities replace their entire membership in just four years, so their organizational base in universities could disappear quickly. Furthermore, New Left sects were waging violent conflicts with each other here and there, so they quickly lost their already weak mass base.

The JCP also frequently engaged in violent conflict with New Left sects during the period when the students were politically radicalized, but for the JCP this was merely a temporary tactic, whereas for the New Left, the use of force was a strategy and even their identity. The New Left completely rejected the Socialist Party and the Communist Party because of their parliamentarianism, so they had to continue to take violent action even if the means became increasingly unsuitable in a later period. After losing their mass base in universities, they sought a sphere of activity in the Sanrizuka movement, which was gaining momentum in opposition to the construction of the new airport Narita, and in various small anti-discrimination movements, and eventually this developed into an extreme situation where members of opposing organizations were killing each other.

The extremity of actions taken by the New Left can be explained by the narrowness of their social base. Having only a specific foundation of politically radicalized students (particularly male students), the New Left shared the same fate; namely, their temporary rise and rapid fall. When even radicalized students went to work for private companies, they quickly adapted to harsh management climates and generally became conservative. Due to the extremity of the gap between relatively liberal universities and the overly totalitarian order of large private companies, the student rebellions at universities in the 1960s and 70s ultimately did not lead to the liberalization of society as a whole, and ended in a bloody internal conflict between extreme sects.

The JCP also sought an organizational base among the universities that had become radicalized in the 1960s and 70s, but for the JCP this was just one of many social bases, and so they did not excessively adapt to their radical sentiments. The JCP’s main social base was still the social periphery, which consisted of people of all ages and sexes from various classes, and the majority of them were non-violent and oriented towards steady grassroots activities. Therefore, even after the students at the universities became generally conservative, it was still possible to maintain organizational foundations based on these peripheral strata.

Another major difference between the New Left and the JCP related to political intergenerational continuation. The New Left, which relied solely on the radicalism of a particular group at a particular time, was unable to pass on the politics of their generation to their children. In contrast, the JCP placed importance on intergenerational succession, and as part of this objective, they published a large number of diverse cultural contributions (ranging from sports and music to entertainment, novels, and manga) in their newspapers, and edited them so that they could be enjoyed by children as well as adults, and by women as well as men. In particular, the weekly newspaper Sunday Akahata (Akahata Nichiyō-ban), which was first published by the JCP in 1959, was designed to be enjoyable not only for supporters of the Party, but also for a wide range of the general public that was made up of people of all ages. The circulation of this paper steadily increased, reaching over 3 million copies in the 1970s.

※ ※ ※

As we have seen, the JCP has expanded and maintained its organization by relying on its broad and diverse peripheral strata rather than on core workers belonging to large private and public enterprises, or on radicalized students at universities. However, even these strata had inevitable limits.

The wave of young workers who poured into the cities from the countryside came to a standstill in the second half of the 1970s, due to the shift to low growth in the Japanese economy triggered by the oil shock of 1973 and the large-scale public works policies pursued by the LDP government in rural areas. The number of local government employees also began to decline from the 80s onwards due to austerity and neoliberal policies. Numbers of workers in small factories and the self-employed also followed the same course of decline in the context of low economic growth and neoliberalism. As the incomes of middle-class workers increased during the period of high growth, they began to buy detached houses and condominiums in the suburbs, and traditional local communities began to decline. Furthermore, the younger generation gradually integrated into the dominant bourgeois culture through television and popular magazines. (The internet in the 21st century further integrated the younger generation into the dominant bourgeois culture.) In this way, the peripheral classes and strata on which the JCP was based clearly began to stagnate or decline.

The decline in the Party’s organizational strength is most clearly shown in the change in the number of copies of its official newspapers (a daily publication and a weekly). It reached a peak of around 3.5 million copies in 1980, butbegan to gradually decline, falling below 2 million in 2000 and finally below 1 million from 2019.

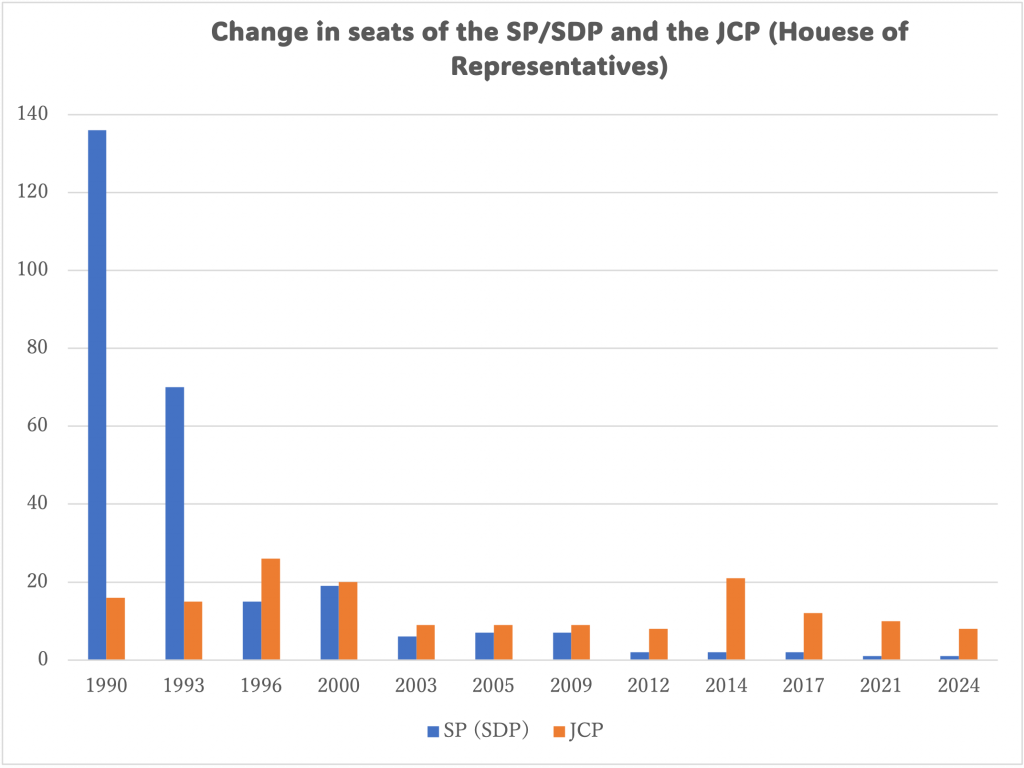

Nevertheless, because the organizational core of the JCP, primarily composed of younger generations acquired in the 1960s and 70s, existed on a scale of several hundred thousand members, the Party has managed to retain a certain political foothold even today, despite experiencing organizational stagnation in the 1980s and 90s and a decline in the 21st century. This stands in contrast to the JSP (now the Social Democratic Party), which is in a state of near-total political collapse.

However, the younger generation that was organized into the Party primarily in the 1960s and 70s (the so-called Baby Boomers and its slightly younger generation) has now become fully elderly amid the overall decline in birth rates and the aging of the Japanese population. Neither Fuwa Tetsuzō, who succeeded Miyamoto Kenji, nor Shii Kazuo, who succeeded Fuwa, were able to devise a new strategy that would enable the Party to make a new organizational advance in Japan’s long declining era. Now, in this situation, the Shii leadership (most recently Tamura Tomoko) pursues the organizational expansion policy of the Miyamoto era again, even though the social conditions that formed the basis for its success have already disappeared. This holding strategy will not succeed.

In the West, too, the labor movement has been pushed back by neoliberalism, but, compared to Japan, traditional labor unions are still going strong, and the Western Left is still able to rely on them. Furthermore, since the 1960s, the emergence of a large number of highly educated people, their general liberalization, and their rise to socially dominant positions provided the Western Left with a new social base (although this also brought about another serious problem of the Western Left becoming elitist and distancing itself from the masses). However, as mentioned earlier, core workers in Japan are overly conservative, and the traditional labor-union movement is extremely collaborative and conservative, so it does not form the basis of the Left. On the other hand, it is true that a mass of highly educated people has emerged in Japan, but this social class is small here compared to the West, and in general they have not become very liberal (or if they are liberal, it’s neoliberal), so they have not become a new basis for the Left.[8]

The above factors have led to the current situation in which the traditionally conservative ruling party, the LDP, remains strong despite the severe circumstances of Japan’s long-term economic decline and the increasing impoverishment of workers, while the liberal and workers’ opposition parties remain remarkably weak.

The JCP has a stronger organizational foundation compared to liberal opposition parties, but its supporter base is extremely narrow. On the other hand, the liberal parties have much broader supporter bases than the JCP but suffer from weak organizational structures. Therefore, for a time, an electoral cooperation strategy between the liberal opposition parties and the JCP was pursued in an attempt to compensate for each other’s weaknesses. However, this ultimately failed. This was because the organizational strength of the JCP had already waned, and opposition candidates jointly endorsed by the parties failed to gain organizational support from the JCP great enough to outweigh lost public support as a result of having cooperated with the JCP.

Meanwhile, the once-powerful LDP has been on a gradual decline since the assassination of its charismatic leader, Abe Shinzō, in 2022 by a disillusioned young man.[9] As a result, the JCP, the liberal opposition parties, and the conservative ruling party are all currently in a state of chaotic uncertainty. In these circumstances, there is a good chance that Right-wing populist parties will rise to prominence, just as they have in Europe.[10] At the moment, this is still only in its embryonic stages in Japan. However, if the major conservative and liberal parties continue to decline, who knows what might happen?

The JCP must make a concerted effort to organize people in a progressive direction who are left behind by the major parties: the huge number of non-regular workers, non-elite women, poor farmers, small shopkeepers, and non-elite immigrant workers. These people are far more dispersed, far more isolated, and far more difficult to organize than the younger generation who moved collectively from rural areas to cities for employment in Japan’s high-speed economic growth period. However, these are precisely the people who, if left unattended, could be absorbed into Right-wing populism, but also who, if the Left finds the right means and methods to engage with them, could become the driving force for a new progressive social change. |P

[1] See “JCP history book, ‘100 Years of the Japanese Communist Party’ published,” Japan Press Weekly (July 26 2023), <https://www.japan-press.co.jp/s/news/?id=14771>.

[2] The overall picture of the Party’s 100-year history as seen by the party leadership is outlined in a speech by Shii Kazuo (then Party Chair), “Talking About the 100-Year History and Program of the Japanese Communist Party: Commemorative speech on the 100th Anniversary of the founding of the JCP” (September 17, 2022), <https://www.jcp.or.jp/english/jcpcc/blog/2022/09/jcp100-year.html>.

[3] 連合国軍最高司令官総司令部. General Douglas MacArthur held the title of Supreme Commander, beginning on August 14, 1945.

[4] The Red Purge (レッドパージ) was carried out by the Japanese government and private corporations with the encouragement of the SCAP; tens of thousands of alleged members and supporters were removed from their jobs.

[5] The JSP (日本社会党) was founded in 1945 by members of pre-war proletarian parties, including the Shakai Taishūtō (Socialist Mass Party); it dissolved in 1996 to become the Social Democratic Party (社会民主党).

[6] The LDP (自由民主党) was founded in 1955 through a merger of the Liberal Party and the Japan Democratic Party.

[7] Minsei (日本民主青年同盟) was founded in 1923.

[8] See Morita Seiya, “Japan’s 2021 general election and its crisis of democracy,” Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal (January 21, 2022), <https://links.org.au/japans-2021-general-election-and-its-crisis-democracy>.

[9] See Morita Seiya, “When the chickens came home to roost: Behind the assassination of Shinzo Abe,” Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal (July 23, 2022), <http://links.org.au/chickens-came-home-roost-assassination-shinzo-abe>.

[10] See Morita Seiya, “Right-wing populism and historical fascism: Traverso’s new book on postfascism,” Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal (July 18, 2021), <http://links.org.au/right-wing-populism-historical-fascism-traverso-postfascism>.