Abolition and the Left

Timmy Chau, Naomi Crane, CJ Meike, Andy Thayer

Platypus Review 156 | May 2023

On November 3, 2022, the Northwestern University chapter of the Platypus Affiliated Society hosted this panel. The panelists were Timmy Chau (director of the Prison + Neighborhood Arts/Education Project, co-founder of Dissenters), Naomi Crane (Socialist Workers Party (U.S.)), CJ Meike (Chicago Workers’ School, Center for Political Innovation), and Andy Thayer (Gay Liberation Network). D. M. Mathis of Platypus moderated the panel, the video of which is available online at <https://youtu.be/kQc9JOtajUY>. An edited transcript follows.

Introduction

Following the 2020 George Floyd protests, police and prison abolition became major demands on the Left. Yet, two years later, though the movement for abolition has seemingly waned, police and prisons remain. Why do police and prisons exist? How do police and prisons relate to capitalism historically? What kind of politics would be required to abolish police and prisons today? What was the potential of the George Floyd protests and what lessons have been learned since? What is the role of the Left in police and prison abolition?

Opening remarks

Andy Thayer: The first thing I’d like to say is that, to its eternal credit, Black Lives Matter (BLM) raised the issues of what to do about the state and its core components, the police and the prisons, on a mass scale for the first time in over a generation. That’s something we all owe an enormous debt to, but these questions were not original to the BLM movement. Actually, if you go back to Marx talking about the Paris Commune of 1871, he first talked about the need to abolish the state and the core of the state. Not coincidentally, Lenin talked about the same issues in August 1917 in reference to the revolutionary situation in Russia following the overthrow of the Tsar. It’s not an accident that those two earlier thinkers began formulating their ideas about the state, perfecting them if you will, in relation to these revolutionary events. To put it in crude terms, the state is a necessary vehicle of class rule. The core of the state is the police and the prisons. This is the mechanism by which inequality is maintained and augmented, and it’s no accident that policing in black and working-class neighborhoods takes on a very different flavor than in Streeterville. The idea that you can get rid of the nasty aspects of the state is frankly utopian.

I participated in a number of demonstrations organized by BLM activists. I can’t claim to be an expert on some of the leading thinkers — Mariame Kaba, et al., who were the intellectual core of that movement — but nonetheless, the idea of abolishing the police and prisons was popularized by that movement. That popularization sometimes took the form of “we need to have a revolution in this country to overthrow capitalism and the state,” and other aspects made it sound like, “we can get rid of the nasty aspects of the state this side of capitalism.” I don’t think that the leading thinkers in the BLM movement, the people that the core activists looked to, thought that, but it’s understandable that there was that ambiguity. The notion that we are going to get rid of the Chicago Police Department this side of capitalism by totally defunding it is utopian. But it was so important to have that conversation initiated, because in this city the police-per-capita ratio versus civilians is the third highest in the U.S. of any city over 50,000 people. That’s 650 cities, and we’re number three. Anyone who has lived in this town as long as I have will tell you that every mayoral candidate will say they’re going to hire more police, which is how we got to that awful situation. Obviously, we’ve got a huge problem with not just communal violence but with police violence, but that’s another discussion. As Marx, Lenin, and Engels put it, the state arises as a result of irreconcilable class contradictions, and the core of the state are the armed bodies of men, to enforce that inequality.

Much of the Left has never agreed with these questions even being raised by the BLM movement. Probably the biggest movement that we saw on the Left in the past few years besides BLM was the Bernie Sanders movement. This spread mightily the whole idea that you can take control of the existing state, or one of its political parties, and use that political party to take control of the state and turn the state into something nice, warm, and fuzzy. To anyone that looks around the world and at the history of the U.S., this government has never flinched from overthrowing other governments around the world at the slightest “provocation,” invading them, etc. This whole notion that you can take over one of their parties and take over the state, was a disservice to building a revolutionary movement. That said, it’s important to say that things can be won versus this awful state, as we’ve seen in some of these reforms, like ending the cash bail, that are under mighty assault in the state of Illinois. We shouldn’t just say, “we can’t get rid of the police this side of capitalism.” We can defund them considerably, since they represent some 40% of the city of Chicago’s operational budget. There are reforms that can be won, but we shouldn’t have any illusions that this is going to turn the state and its police into some warm and fuzzy creature.

In The State and Revolution (1917) — I flipped back through it when I was invited to do this panel because it raises the questions in clear form — Lenin says that so-called “democracy” is the optimal political form for capitalism, because it’s easier to persuade people to follow their roles in capitalism, producing wealth, etc, than using blunt force. It’s harder to get people to believe somewhat in the fact that the current system is legitimate when your police are repeatedly cracking heads. Unfortunately, that breeds lots of illusions in the Left, as we’ve said with the Bernie Sanders movement.

These are not new issues. The breath of fresh air is that the BLM movement raised them in a way that brought down on them the wrath of the Democratic and Republican Parties. If anything tells you that you’re doing the right thing, it’s when they both hate you that much.

Timmy Chau: On the question, “what are the prisons and police in relation to racial capitalism?” — As a young person who was politicized during the BLM movement around 2013–14, abolition was the hegemonic frame for a lot of young folks who were being politicized, particularly around issues of police brutality and mass incarceration. Abolition is recognizing the function of the state, specifically the role that the prisons and police play as the hands and arms of the state and capital in disappearing surplus populations. Not just disposing of folks, but also being the arm of domination and extra violence upon communities that have been deemed disposable and less than human, specifically in the U.S.

The state maintains the status quo. It’s the mediator of maintaining the status quo of class relations. Abolition is a vision, direction, political program, and a guidemap to working toward a stateless and classless society. As an organizer, it is a clearly strategic frame to focus on, and a target that unites many impacted communities that are feeling the brunt of capital and the state, the violence of the state. The strategy is to focus on trying to chip away and make less powerful institutions that are impacting people’s lives. There are folks in the abolitionist movement that are working on targeting the carceral state, policing, ICE[1] detention facilities — the mechanisms of state violence that are used to deal with folks that have been slipping through the cracks of the economy.

I saw the fliers “Abolition and the Left question mark,” and my response is “duh, yes.” Abolition is strategic because, through the work of many abolition leaders who have popularized that kind of framework, it’s not just a plan to transform material conditions, but is also getting at the insidious cultural, ideological foundation that enables the U.S.’s state and capital relations. Specifically because it’s forcing us — through transformative justice, restorative justice, and all these kinds of cultural frames and relational frameworks — to ask questions about how we deal with harm and who is deserving of access to life-affirming resources and the social wage, etc. It’s forcing us to ask those questions to counter the carceral, punitive disposability culture that is also connected to the U.S. empire culture of violence, militarism, disposing of less-than others.

For example, a lot of my comrades are locked up inside, dealing with life sentences. For many of them, abolition represents an opportunity to shift and change the dominant state structures that have rendered so many populations disposable and thrown away. The principles and values that undergird abolition also force us to transform the cultural values that enable the racial capitalist status quo in the U.S.

Abolition is a massive movement with multiple tendencies within it. There’s what I describe as revolutionary abolitionists, who believe that the U.S. state apparatus must be totally demolished. Others believe that not the whole state, but some parts of the state are redeemable and have served useful functions for society. There are more liberal factions in the abolitionist movement, who do more legal reform work.

There’s a question here about what we can learn from the George Floyd uprisings and rebellions. They demonstrated just how weak the Left is in the U.S. We had days and weeks of sustained militant uprisings and insurrections across the state. Part of the role of the Left is to facilitate, support, and push those demands further, to build the capacity, networks, and resources that can sustain revolutionary ruptures for as long as possible. The Left should translate that into the most radical political demands that we can wrench out of the political decision makers wherever you are. You had cities that were ready to disband their entire police force within a week. Then activists and nonprofits came in, and those demands shifted quickly into more legislative demands, and once those revolutionary ruptures closed up, the status quo hopped back in, and abolition became a non-question again, regarding cutting budgets, etc. The Left in the U.S. has a long way to go to be able to make the most of when these conditions combust. The growing non-profitization of social-change work in the U.S. is unique. I have to do more international travel to understand the role of NGOs and nonprofits everywhere. But the way it does defang, water down, and co-opt these moments and ruptures was abundantly clear in the wake of the Goerge Floyd uprising.

Naomi Craine: The Socialist Workers Party (SWP) is building a party of the working class, not the Left. We start with the crises that are caused by the dictatorship of capital that we live under, which are not just the economic things, the inflation and the wages that don’t keep up with it, but also the moral and social crises — the breakdown of the family and of solidarity, the growing rates of suicide, drug and gambling addiction, mental illness, and the wars that capitalism inevitably produces. We start from the fact that the only road out is the working class and other exploited classes taking power. There’s no way to reform capitalism. To realize our potential, workers need to throw off the self-image that the rulers and their lackeys promote among us, that we can’t do anything. We need to see that the working class is the progressive class in society — the force capable of building a society that’s based on solidarity and not a dog-eat-dog race for profits. Friedrich Engels in 1847 said, “communism is not a doctrine but a movement, it proceeds not from principles but from facts.”[2] In other words, it’s not a set of ideas and ideology; it’s the line of march of a class, the working class, towards political power. The massive protests that we saw following the death of George Floyd reflected the widespread anger over police brutality and racism among working people of all skin colors. Especially significant was the scope of these protests: not just in the cities, but in small towns across the country. There are many workers and young people that took to the street for the first time in their lives.

These protests, however, were quickly undercut by those who carried out looting, burning stores, and so on. There was a whole layer of anarchists and some elements within the BLM organizations that organized or justified these kinds of anti-working-class actions. And there was a layer that increasingly prompted race-baiting, saying, “there is systemic racism and the problem is white people,” not “the problem is capitalism.” The system is capitalism. At the same time, the protests were channeled by liberals and much of the Left into various types of reformism in the form of saying, “we need to elect the Democrats because they are the lesser evil” — although the Democrats are the largest party of imperialism in the world today. They also did so through reformist slogans like “defund the police” or even “abolish the police.” The role of the cops and prisons in capitalist society is to protect and serve the interests of the ruling class. The capitalist state’s laws and the way they’re enforced are designed to keep workers in line and to brand a substantial layer of us as criminals, particularly those who are black or are from other oppressed nationalities.

At the same time — and this is of great concern to workers — capitalist society produces antisocial violence within working-class communities. In addition to the immediate consequences, this breeds fear and demoralization in the working class. It saps our confidence and tears at social solidarity. This in turn feeds more antisocial behavior and spreads the infection of the dog-eat-dog morality of capitalism, which comes straight from the top. Workers live in the real world with its contradictions. Campaigning in neighborhoods, I can’t tell you how many people told me about how they don’t like the cops. They will tell you all kinds of stories about themselves being profiled, facing abuse from the cops, and, at the same time, don’t support the idea of defunding the police or abolishing prisons. This is because they know it is better to live under the capitalist rule of law than what the immediate alternative, if you just got rid of it today, would be: the rule of gangs and vigilantes.

The SWP joins in fights against police brutality, frame-ups, abusive prison conditions, and the death penalty. We work to build support for these fights within the labor movement, which is important; it’s part of building working-class solidarity on the broadest level. But we have no illusions that the fundamental character of bourgeois so-called “justice” can be reformed. The Cuban Revolution provides the example of the road forward. When workers and peasants took power there in 1959, they didn’t try and reform the henchmen of the Batista dictatorship, nor did they drag them through the streets and lynch them. They said, “we’re not having vengeance,” which is important because of what that does to your solidarity, your own self. They disbanded the former cops and replaced them with tested veterans of the revolutionary struggle. They put the worst torturers in prison, and offered other jobs to the rest of them. The new police force was based on new class relations, where the government represents working people instead of attacking them.

To be in the strongest position to organize, the working class needs to jealously defend the Constitutional rights and protections that we have won over more than 250 years of class struggle. This includes freedom of speech, assembly and worship, freedom from unreasonable search and seizure, the right to trial by jury, the right to confront your accuser, and much more. Any violation of these protections, no matter who’s the target, will come back against the working class. Attacks on democratic and Constitutional rights come from both the Right and Left in bourgeois politics, but today they are especially being driven by the Left. I want to give a couple of examples. One is the trial of Derek Chauvin. We were among the hundreds of thousands that demanded he be prosecuted for killing George Floyd. The ruling class quickly, in the face of those protests, decided to cut their losses and throw a few of their beat cops under the bus. Once they decided to do that they used the same methods that they used when they wanted to go after one of us. They carried out a show-trial atmosphere; they refused to move the venue of the trial. There were prejudicial statements up to Joe Biden saying he should be convicted, prior to the jury making its verdict, and much more. Then they carried out double jeopardy: he was tried a second time for the same thing under federal charges after being sentenced to 22 years in prison. All of this weakens the working class and fighters against police violence and abuse of our rights. Another example: today there’s a big effort by the Democrats to get Trump at all costs, which includes ramping up investigations, using the FBI and trying to refurbish its image, which is tarnished among working people in general. But the FBI remains the political police of the ruling class. It has been and will be used principally against the working class and its vanguard — against the unions, against black-rights organizations, against working-class parties.

Over the last couple of years we’ve seen enough strikes and other struggles to confirm that the low point in working-class and labor resistance is behind us. Members of the SWP are part of fights against the bosses by the trade-union struggles in the bakery-workers union, the rail unions, and elsewhere. We work with fellow union members and others to strengthen the unions and use union power. It’s the only road to build a labor movement that fights in the interest of the whole working class, and a socialist revolution in the U.S. is inconceivable without organizing our class to fight to build unions and to use union power in the interests of working people around the world. The SWP and our candidates explain the need to build a labor party based on the unions, and to break with the Democrats, the Republicans, and all other capitalist parties like the Libertarians, Greens, etc. In campaigning in working-class neighborhoods, at factory gates, and elsewhere, we find a broad discussion taking place in the working class on the whole range of questions that we are facing today. The big debates and conflicts today are not between red states and blue states; they are at root class questions.

I want to end by recommending two books in particular. One is The Turn to Industry: Forging a Proletarian Party (2019) by Jack Barnes, who’s the national secretary of the SWP. It talks about what kind of a revolutionary working-class party needs to be built, drawing upon the experiences of the SWP over the last four decades. And the other is Malcolm X, Black Liberation, and the Road to Workers Power (2009), also by Barnes. This talks about how, in the last year of his life, Malcolm X became a revolutionary leader of the whole working class. How Malcolm X explained that there’s a clash coming between the oppressed and those who do the oppressing, but it’s not going to be based on the color of skin, as Elijah Muhammad has said, and as Malcolm X said in his time in the Nation of Islam. In one of the last interviews he gave, Malcolm said — he’s trying to wake his people up, and the interview asks, “what, to their oppression?” — and he says, “no, people know they are oppressed. To wake people up to their self worth, to their capacities, to their humanity.” And that’s what my party’s trying to do as well.

CJ Meike: In this moment of emerging multipolarity, a period that promises — we shall see with what sincerity — not one hegemonic power on the world stage with its vassal clients and puppet regimes, but multiple powers without any one being dominant. We are beginning to see with some clarity the trajectory of political and economic development of U.S. foreign and domestic policy. This policy can be accounted for in two words: aggression and reaction. Aggression, in that U.S. imperialism, like a beast in a prolonged death spiral, is lashing out in all directions, attacking not only countries that dare to step outside of its so-called rules-based international order — Russia and China first and foremost, even little Haiti — but in due time, also its own domestic working class that will seek to free itself from increasingly repressive conditions and declining standards of living. Reaction, in that this lashing out is a product of the need to hold back historical development. It is the insistence that the so-called “end of history” has not itself ended. Abroad, increasingly sovereign states will become subject once again to the pole of history towards socialism. At home, the working class is feeling the effects of living in an empire in decline. The time will soon come when they will look to the likes of us for ideological clarity to explain their declining state and the way out of it. The imperialist bourgeoisie and their state lackeys will, of course, seek to prevent this union of the working class and the politics that offer it salvation, by rolling back workers’ hard-won liberal rights, and to quote Georgi Dimitrov, by instituting an open terrorist dictatorship, the most reactionary, chauvinist, and imperialist elements of finance capital — fascism, in a word.

This is the context in which we must analyze all questions. The question today is about police, prisons, and the slogans demanding the abolition of both, particularly in the context of the 2020 protest movement commonly known as the George Floyd or BLM protests. I ask the listener, even before going into the classical Marxist theory of the state, if such slogans as “abolish the police” or “abolish prisons” fit into the plans of the bourgeoisie in the trajectory I’ve outlined, and I’m not alone in outlining. The answer clearly is a resounding no. We shall look first to Lenin, perhaps the foremost of Marxist theorist-practitioners. This is a good starting point for most inquiries. In The State and Revolution, Lenin begins the section “Special Bodies of Armed Men, Prisons, etc.” with a quote from Engels describing the origins of the state as a necessary product of the division of human society into classes. This following quote summarizes the historical materialist understanding of the state and its repressive institutions:

“This special, public power is necessary because a self-acting armed organization of the population has become impossible since the split into classes . . . This public power exists in every state; it consists not merely of armed men but also of material adjuncts, prisons, and institutions of coercion of all kinds, of which gentile [clan] society knew nothing.”[3]

What Engels is pointing out is that class society demands class rule — dictatorship of the class of exploiters over the class of exploited — and that as soon as this new form of politics and economy arose out of primitive society, there also arose institutions required to force the exploited class to submit to these antagonistic conditions. At the most general level, we and countless generations of our ancestors have lived under these conditions since the origins of class society. Lenin goes on to point us to another line of Engels: “‘It [the public power] grows stronger, however, in proportion as class antagonisms within the state become more acute.’”[4]

To think these lines of Engels were written not in 2022, but in 1891 when the state was still quite primitive in relation to that which weighs on our shoulders today! As another example, we can look to the police states of post-Soviet Eastern Europe that would put any exaggerated notions of the Stasi of the GDR to shame.

Class struggle is presently awakening and will reach higher and higher levels. While it is possible that the ruling class will offer concessions, illusions, and magic tricks of all kinds, it is impossible that they will disarm themselves just before this upcoming period of class struggle and possibly class war. On the contrary, and to the great surprise of those advocating these slogans — yet no surprise to materialists — imperialists will increase, not decrease, levels of state repression. Lenin, by resurfacing these words of Engels, is pointing us to the fact that not only are these institutions of repression — police and prisons — central aspects of class rule, but that they are inseparable from class rule. The only way that these can be abolished in substance and not just in name is the abolition of class society, their material foundation — communism, the highest stage of socialism. This is the only materialist form of abolitionism. Even when the proletariat has seized power, these repressive apparati — similar though not identical to police and prisons — will need to be created under the proletarian state in order to serve the interests of the proletariat, that class which was once exploited, over those of the bourgeoisie, that class which once exploited. In the practice of past and present socialist countries, such coercive institutions have been reformulated to serve the working class. Marx also pointed to the need of such despotic inroads on the rights of property. To argue for the abolition of these instruments of class rule is not only a pious wish that the bourgeoisie disarm themselves, but also the treasonous folly of advocating the proletariat yield to a counterrevolution by doing the same. I remind those advocating these slogans that the National Guard, a reserve force of the U.S. Army, was deployed during the BLM protests in Chicago. Even if the police is abolished, Chicago is essentially already occupied by the U.S. Army reserve forces, with somewhere between six to eight armories scattered throughout the city and the suburbs. The path of escalation is police, then the National Guard, then the Army proper. We therefore think in terms of Lenin’s special bodies of armed men, a more inclusive category.

I’ve also been directed by a member of my organization to mention short-sighted and hypocritical tactics of portions of the Left, who cheerlead such institutions in the state so long as they’re repressing their supposed political enemies — think January 6 — but become abolitionists when they speak about their pet causes.

Finally, slogans like “abolish the police” and “abolish prisons” are the opposite of materialist. They are idealist, not rooted in material conditions. They fail to account for the necessity of special bodies of armed men and the institutions of coercion in class society. They do not account for the historical trajectory of U.S. imperial decline. In the final analysis, they confound and mislead more than they clarify, and have no potential to be realized. I suggest those of us aspiring to be Marxists discard these slogans immediately and study the repressive institutions of the state through a dialectical materialist worldview, whence correct slogans can be derived.

Responses

AT: The U.S. spends as much on its military as the next 10 biggest powers. Who here in this audience supports defunding the military? Most of you. What’s the difference then in terms of demanding defunding the police, especially in this city when they’ve got 40% of the operational budget? There was an article in the Chicago Tribune today about the billions that the city is spending on defending these crooked cops. Frankly, I get more than just a little bit upset when it’s posed as a reformist demand and that it would be replaced by rules of gangs and vigilantes. Ronald Watts is responsible for 250 wrongful convictions and people serving decades — Reynaldo Guevara served 35 years of wrongful convictions. I work at a law office. I'm not an attorney nor representing them here, but I will tell you, I’m sick and tired of writing these press releases about these overfunded cops getting off the hook over and over again and nothing ever happening to them. It’s a systemic problem, not just an issue of a few bad apples. It starts right at the fifth floor of City Hall, and that is the core of our state here in this country. You look around the world and listen to the politicians talking about needing to have peaceful relations here in the U.S. That’s all built on exporting violence to Central America, the so-called Third World, right now Ukraine, and any number of other areas of the world. At the core of this state is violence. I totally agree with Timmy — anything that we can do to lessen the power of the state, short of overthrowing it, is important.

When Lenin was writing The State and Revolution, his main argument was with people in his own party who thought that they could coexist with the then Provisional Government, which was so much better than the Tsarist dictatorship. But he made the point that revolutionary institutions could not coexist — in this case, the workers councils, the soviets — with the capitalist government. One or the other needed to win out at the end. It was part of his argument for the overthrow of that Provisional Government by violent means, because that’s the only way that the other side will give up its means of violence — police, prisons, etc.

In terms of saying that the BLM movement was primarily undercut by violence, I can only remember a phrase I heard at a demonstration I participated in. One guy said, “your Michigan Avenue looks like ours now,” which really encapsulated the decades of violence that’s been committed. We’ve already had gangs and vigilantes in this town, and I’m no fan of private gangs, but let’s be clear about what the relations are, particularly in say, K-Town on the West Side, where the police are another gang.

I liked what Timmy said about the role of NGOs. I’ve seen over the decades that the NGOs are not only funded by the state in large part, they are an arm of the state. I’ve seen them defang and lessen the impact of any number of social struggles. Frankly, for those of us who wish for a revolutionary transformation of U.S. society, they are going to be one of our biggest impediments. Previous mass movements in this country, going back to the 1930s, didn’t have that dead weight of all these NGOs. You started to see them in the 1960–70s. It was a conscious policy of Nixon and LBJ to fund these NGOs to try to control the process of reform that they saw as necessary.

I was a proud participant, as were many people in the room here who are old enough to remember, in the big 2003 demonstrations against the then impending Iraq War. The New York Times had a phrase saying this is now the new superpower. I tried looking it up and couldn’t find it, but it was like, “these are the biggest mass demonstrations that the world has ever seen.” Those of us who were part of that demonstration took over Lake Shore Drive. But at the end of the day, the fuckers slaughtered countless Iraqis, Afghans, and others. We had a mass mobilization, which is good for getting people involved in politics, but mass sentiment alone is not enough to do the job. We saw with the BLM movement — which was seen as the largest demonstrations to date in this country — mass sentiment, particularly amongst youth of all races, but again, it was not enough to overthrow the state. We should look to defunding the military and police as goals — goals that we are not going to be able to achieve short of overthrow of the violent state, which will not allow itself to be peacefully voted away. But they’re goals that we can achieve, real gains. It’s pretty funny: the best mayoral candidate that you’ve got in the current election is the one saying he’s going to freeze the budget of the police — this budget that’s already way up here. In the last mayoral election, all of the candidates — even the best of them — said they were going to increase the funding of the police. Small progress there, but we need to not lose track of who the biggest gang is in the city of Chicago.

TC: I do work in prisons and anti-war work. One of our specific goals has been to make the domestic and international connections of abolition. It’s not a coincidence that the police budget locally could be overlaid on the military budget nationally. It’s not a coincidence that we exported the prison system in Iraq after the war started. We’re literally exporting the prison-industrial complex around the world through empire. Abolition is a frame to make those connections. Abolition domestically, tackling the police in prison here, is a part of an anti-imperialist struggle more broadly.

On the NGO thing, I’ve spent too much time reading military manuals. It’s not new — these are the tactics of going into communities of colonized and warring populations. That’s one of the first tactics: we’ll meet your needs to maintain control, but only as long as we’re the ones controlling the type of resources that you’re getting — a limited infrastructure in a war-torn situation. Their new counterinsurgency tactics are continually being deployed domestically as well as internationally.

I work in Stateville, in Joliet, Illinois. This is predominantly white, working class in certain pockets, but most of the jobs of the city are workers at the prison. In the prison, there’s a mural with a prison guard in half Orange Crush uniform, which the guards wear when there’s a riot inside the prison, and half military outfit. Not only do these theoretically-materially connect certain parts of the same empire, but Sheriff Tom Dart in Cook County just said he’s going down south to recruit veterans because you can’t find workers in Cook County Jail.

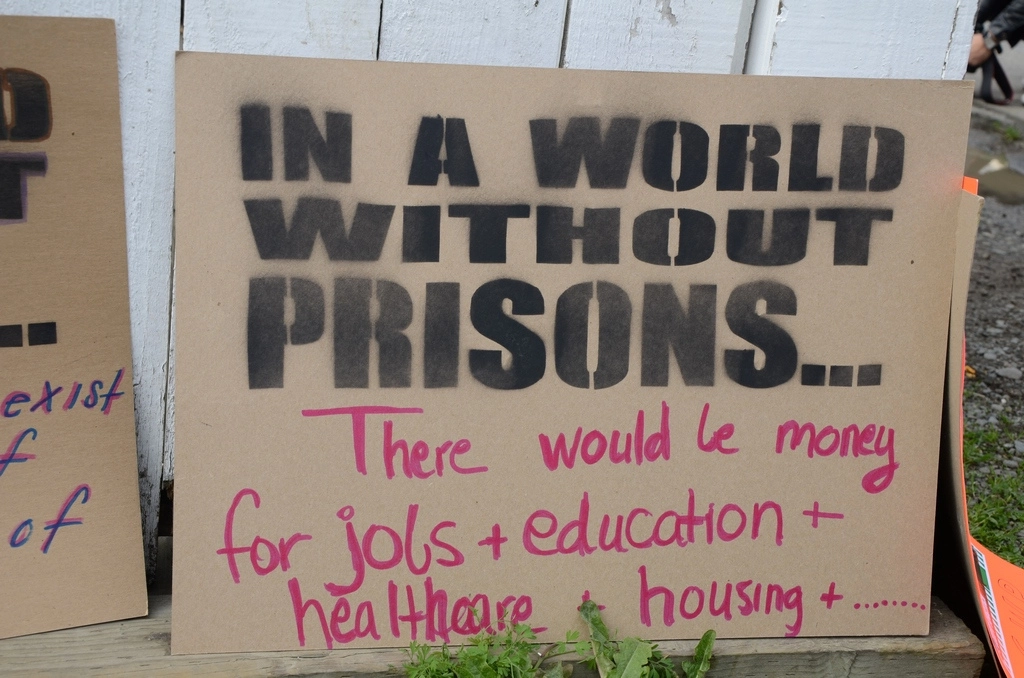

Abolition is a generative politics. It is not just a disruptive one, which I hate having to go on the defensive to say, because there’s much for us to destroy. Abolition is about building the world that makes prisons and policing obsolete. Part of that is communities having everything they need to thrive, and where a culture and systems of containment, disposability, and domination become obsolete. We don’t need them because of communism, everybody’s needs being met — food, housing, healthcare. That is all a part of what it means to be an abolitionist and work toward an abolitionist horizon.

I strongly caution us from focusing on the looting and the role of anarchists in the George Floyd uprisings as the reason for their failure. Whether or not you believe or disagree with that stance, to be talking about that in the context of particularly poor black and brown communities is unprincipled and not the primary contradiction that we should be focusing on. If anything, it’s the same language that the state is using to justify more policing. I’m saying this as an anarchist who was targeted by the state for taking militant direct action against corporations. That same talking point was used by the state to criminalize me and a bunch of my comrades and political collaborators.

If we are on the same page that we need some united front across tendencies, the working class and different classes, we’ve got to stay clear on who the main enemies are and not throw each other under the bus, especially when that’s going to end up risking further criminalization and expanding the state. Also, we’ve got to dump the vanguard talk. There’s people going to be looking to us as organizers and seeking revolutionary horizons. We need to be collaborating, learning, and seeing the needs of communities and sensibilities that are already being demonstrated within the uprisings and reflecting those back and facilitating deeper collective understanding of what needs to happen. It’s not that we’re going to save people. That’s just not going to work, and it ends up, depending on the racial makeup of who the vanguard is, replicating the same racist hierarchies and disparities of power post-revolution.

I encourage folks to do some reading around racial capitalism. Race is always a modality in which capital is lived. There have been theorists that have pushed us past “we can’t talk about making it about race when it’s about class” — it’s always both.

NC: Yes, there’s a connection between the armed bodies of men that the state uses militarily and domestically. But what do you replace them with? How do you get rid of them? We say not one penny, not one person for the imperialist war machine. At the same time, the founding program of our party in 1938 says, “disarmament,” but who’s going to disarm whom? The ruling class is not going to give up their arms. They need to be disarmed, but there’s no abstract slogan of disarmament. What’s needed is to replace the class dictatorship of the capitalists and the armed bodies of men with a workers’ and farmers’ government led by the working class.

The example of the Cuban Revolution is valuable. The rebel army fought to overthrow the Batista dictatorship. They forged a cadre of disciplined workers and peasants. They didn’t have vengeance. Those attitudes extended to after taking power, when they disbanded the police, the military, all the repressive forces of the old regime and created new institutions of class rule of the majority. They were based on the cadres that had gone through that.

Sometimes when there’s big protests around police brutality, the cops — here, in New York, Minneapolis, and other cities — will pull back from policing the working-class neighborhoods. They’ll say, “let them kill each other, and we’ll show them that we’re needed.” You see a spike in all kinds of antisocial things that have a devastating effect on individuals and communities. I’m not arguing for having more policing of communities, but I’m talking about the reality that exists within capitalist society. There’s workers and others who become declassed and lumpenized. That’s a lot of what the gangs do. The violence of the gangs is an extension of the violence of the ruling class. I work on the railroad — they’re slashing jobs and making conditions much more dangerous, both for the workers and for anybody who lives near railroad tracks. They will do actuary of what it will cost them in settlement payouts to cut corners on safety. All of these big companies do this. But we start changing our nature as human beings as we start organizing together. When you see big social movements, that’s when you see decline in street violence. At the height of the Civil Rights Movement or the big union battles in the 1930s, you had a decline in that kind of thing. Yes, the cops act as a gang. But when many workers hear “defund the police”, they say, “no” — and it’s for good reasons. It’s got to be a question of, what kind of movement do we build, and what builds confidence?

On the question of the looting, I went up to Kenosha a couple days after the cops shot Jacob Blake there. You’ve seen a massive immediate response in the community against this outrage of shooting this unarmed black man. But then you also saw the reaction — a lot of the shops were still smoldering. I was there in the afternoon on the third day before the events where Kyle Rittenhouse shot the three people there. Talking to people in the park and neighborhoods, a lot of workers who wanted to go out and protest the police brutality were dissuaded from joining a fight, and a lot of people were sympathetic to protesting against what the police had done. If you start burning down the stores and the gas stations, it does undercut the struggle, and it’s not an effective form of fight. It is important for us to discuss this; it’s not throwing each other under the bus.

CM: To build off that, what kind of class alliance does the U.S. need? Naomi said earlier,

“workers and farmers,” but perhaps there’s a role for the petty bourgeoisie. I don’t think that’s how you make friends with the petty bourgeoisie — looting, burning.

Looking at these mass movements — what would traditionally be called spontaneous movements — there is a problem of leadership. To a great extent, the Left today tails. It follows, but it doesn’t develop the consciousness or expand the demands of whatever mass movement arises. That’s partially why we keep going in these spirals without getting anywhere. Someone else mentioned anti-Iraq War demonstrations in 2003. It’s a question of leadership. I made a point of saying there were 15 people in my organization, so we’re not near that by any means. But the leadership needs to have this revolutionary theory. There can be no revolutionary movement without revolutionary theory, Lenin tells us. The workers on their own can only develop a relatively low level of consciousness. In dialogue with the advanced section — the vanguard — we can develop and elevate workers’ consciousness. We take workers where they are, but then we want to develop them to be more conscious, and we want the most advanced to have a greater theoretical understanding of the way the world works. I can’t stress that enough. The working class will revolt, but the question is, will it do anything? The first thing to do is develop theoretical understanding within a group of people so that they can become leaders. The goal is to create a party.

The way one of our co-panelists puts abolitionism — I wonder why we need a new term if essentially it’s communism. Why not just say communism?

TC: On the claim that looting wasn’t effective — whether or not you agree with it morally — the ruling class was scared and ready to concede some elements of reformist policy. That was my metric, and by those standards it was the most effective moment of expression of political power against the ruling elite I’ve experienced in my life. You had entire city councils ready to disband their police forces and fund other social services. That was one of the main reasons I stayed in community organizing: the experience of the uprisings and the potential of what that could mean if we were able to learn, sustain, build deeper networks, and practice better rhythms of sustainability and resourcing local communities. What if we were able to sustain militant confrontations with the state and capital in the ways that were demonstrated and exemplified throughout that summer of the uprisings? That’s the goal. It was the most effective moment, if we’re understanding effectiveness as actual wins and as a chipping away of the status quo.

Q & A

All four panelists are grounding the question of policing — where policing originates, what policing functions for — in the state and capitalism more generally. One discourse that generated, certainly before BLM but especially through BLM, is the particularity of policing with regard to race. It serves to oppress black people distinctively from the rest of the population. What are the panelists’ conceptions of policing with regard to race, how it’s distinctive or not, and what would that mean for the Left in terms of our conception of how to grapple with policing in an emancipatory movement?

TC: It comes back to my point about racial capitalism as a lens to understand the state and capital. It’s not capitalism as something separate from racism; these are systems that are working together. The entire U.S. state apparatus was founded and produced in the context of transatlantic slavery and indigenous genocide. The understanding of who is human and who isn’t is a material reality that informs all the systems that are produced from that ideological understanding. You can’t talk about capitalism without talking about anti-black racism in the context of the U.S. The statistics are used to police and dispose of communities that have been deemed disposable.

CM: The particular oppression of black people under capitalism is a divide-and-rule strategy. It’s not separate from capitalism; it’s not something that runs parallel to it. It is capitalism, and it’s a strategy employed by the ruling class. On indigenous genocide, it’s not a question of who’s human and who’s not human. Speaking in terms of “humanity” is liberal, but also vague. It doesn’t really matter who’s human and who isn’t. We’re all human, and everyone recognizes that. It’s a matter of class interests, and so it’s a question of not being in the class. Indigenous genocide is an American form of primitive accumulation. You can see that in class terms rather than, say, not liking indigenous people or thinking that if we measure their head this way their cranium is somehow smaller. It’s not racism at the root of it; it’s primitive accumulation. It’s class interests.

NC: U.S. capitalism was built not just on slavery. U.S. history is unique, compared to Europe, in that it never went through a period of feudalism. It was capitalist from the beginning, including the form that chattel slavery took in the U.S. The racist ideology was promoted and created in order to justify chattel slavery, but it was also based on exploited labor — North and South — in a black skin and in a white skin. The origins of policing in the U.S. came out of guarding capitalist property. In the North it came out of the night watchman for the factories, and in the South it came out of the slave patrols. It’s been an anti-working-class institution of class rule from the beginning, as are the rest of the institutions of class society. Yes, there is no way you can make revolutionary change in the U.S. without it involving the fight against racist discrimination and its legacies.

But it’s also not accurate to say that American capitalism is based on racism, that racism is the dominant thing. It’s class rule, and racism is one of the parts of it. They are completely intertwined, as is the fight to get rid of them. The working class taking power is what will open the door to finally being able to get rid of racism and the other forms of oppression — the oppression of women, which dates back much further, to the beginnings of class society, etc. Obviously that doesn’t mean that you don’t fight against every manifestation of these things as they are today. That’s part of mobilizing the forces that can lead to the working class taking power and overthrowing the dictatorship of capital. If you look at the statistics on people killed by the police, the majority are caucasian, but they’re disproportionately black and of other oppressed nationalities. Both things are true. The violence of the cops is an anti-working-class violence, but, as in every other aspect of society, things — unemployment, housing conditions etc. — come down disproportionately hard on those who are the most oppressed and exploited, which in the U.S. are those who are black, and at various other times, those of other oppressed nationalities.

AT: I was at a meeting last night where at one point we recounted the many, many broken promises of our current mayor. It was quite a list, but one of the big ones that she actually has made some moves to do something about was to do some modest modicum of funding for the south and west sides, the so-called “INVEST South/West.” Compared to all the other broken promises — from reopening mental health clinics to electinga school board — this is the one she’s actually done a tiny little bit about. You can attribute that directly to the fact that the violence and deprivation, which has been endemic for decades has finally hit Streeterville, finally hit the Magnificent Mile. That’s why INVEST South/West is going on right now.

On this idea of getting rid of the police, if there’s a mass movement, let’s look at what happens during the context of mass movements. Not just in this country, but around the world. When there is a general strike, the first thing that happens is that people begin to say “the state is temporarily not working in our town of, say, Minneapolis / St. Paul circa 1934, and we’re going to have to start organizing medical care, food distribution, and yes, we’ll have to organize groups of trusted people to make sure that there isn’t violence.” You see that over and over again in mass uprisings. It’s not like if you get rid of the police nothing happens. You saw this in limited areas in terms of the BLM movement, in sections of the south and west sides where mutual aid was inaugurated, often by people with few resources. You saw that with the Black Panther survival programs. This isn’t the idea that this is going to be the be-all and end-all, but it was a step in terms of beginning to form that dual power that we saw in full flower in the period between the February Revolution in Russia 1917 and the October Revolution. It was an inherently unstable situation — in Iran it was the shoras, in Chile they had their councils. You have these different forms of self-organization that are not imposed from on high by someone who’s studied revolutionary movements around the world. It’s not proclaimed; it’s earned. It’s earned by being part of the struggle and learning from that struggle, learning more from the struggle itself than any teaching that someone with gray hairs like me might do.

I moved to Chicago recently from Minneapolis and went through that whole experience. It is striking that, yes, the majority of the city council in Minneapolis proclaimed that they were for getting rid of the police, but any serious person never believed that was going to happen, because the ruling class will have their police. In the initial days of the upsurge after George Floyd’s killing, the majority of my coworkers at Walmart were participating in the actions. I have to agree with Naomi: what undercut that participation was the violence that was taking place by those who were burning down property and carrying out other kinds of provocative things. It became difficult to get more broad participation.

I’m happy that a number of panelists pointed to The State and Revolution. Lenin points out that Marxists do share something with anarchists: they are ultimately for the abolition of the state, but they have a sharp difference over how we get to that. Can it simply be abolished or does the working class have to organize itself to constitute itself as a state in order to consolidate the power of workers and peasants? When you come to power, the bourgeoisie and the capitalists don’t go away. I like that there are sharp differences on this panel, but there is civil conversation. Naomi pointed to the Cuban Revolution, but if you look at the Russian Revolution and the fight that Lenin led, including inside the Bolshevik Party, for all power to the soviets — what were the soviets? The soviets were a government, a state of workers and peasants that had come into being through the course of struggle. It was the replacement for the rule of the capitalists. It wasn’t spontaneous either; it was led, just as the 1934 strikes in Minneapolis. How do we build the kind of movement that is able to challenge the capitalists for power and replace their power? We have to make a revolution, but it’s not a question of abolition; it's a question of us organizing ourselves to take hold of the state.

TC: On organizing to take over the state, we need to be clear about material conditions in the U.S. We’re a massive country, and struggling locally is going to look different state by state. There’s not going to be a simple blueprint saying, “this is the moment, the workers are organized, now’s our chance.” It’s going to look messy and chaotic, because the culture in the U.S. is uniquely hyper-capitalist and white supremacist. We’re dealing with a lot, and we’re so vast in terms of land, resources, and political makeup of infrastructure that folks need to start mapping out. As conditions sharpen in different regions, it’s going to look different in the city of Chicago versus downstate, versus in the South versus on the west coast as resources and climate change worsen. I’ve read The State and Revolution. I read a lot of Marxist theorists and anarchist theorists. I encourage folks to read anarchist theory on planning around direct action and structure and organization, particularly around decentralized networks of resource distribution, and places where there are no resources and there are vacuums of power.

This sounds like a postmortem of the whole movement to abolish policing. Do you see it this way? Or do you see this as the first act? If so, where do we go from here? The spontaneity of those demonstrations was remarkable. No one predicted it. Even during these demonstrations, the murders throughout the country continued. The difference is that they were publicized. They were on the nightly news, which is a feature that hadn’t really occurred in my lifetime. I remember Rodney King in 1992 and the eruption there.

NC: Capitalist society is going to generate all kinds of protests and actions in response to things. Look at what’s going on in Iran today. A couple months ago the so-called “morality police” murdered this young woman for supposedly not wearing her headscarf right, and it sparked a resurgence of protests that had been happening for the last several years that intertwine with a number of questions: of women’s rights, of the oppressed nations within Iran, especially opposition to the military adventures of the regime in Iran. The protests at this point, despite the government repression, don’t show any sign of ending. At the same time, until there’s the kind of leadership built — which will partly be built in the course of the struggle — that can actually replace the regime in Iran with workers’ power, there will be ups and downs. You don’t just have continued protests, and then all of a sudden you’re going to have the working class in power without developing some kind of leadership. There will be more protests in the U.S. in response to police abuses and other things. There’ll be big labor battles that’ll unfold because of what the bosses are pushing. The biggest thing that you gain in any of them is broadening out solidarity, interconnections between workers in struggle, and learning from the different experiences. Debating these questions is extremely important. What was striking to me, in terms of the scope of the U.S., was how many protests were in tiny towns and rural areas. It was a response that had to do with not simply the outrage that people felt when they saw that video of Chauvin on top of Floyd, but the whole range of what’s been happening: experiences with the cops but also more broadly with the bosses, and other things working people are facing. We’ll see more things like that.

AT: Whenever I want to depress myself, I think about the immense power of the state. It’s mind boggling. Just the nuclear modernization program of President Obama is up to two or three trillion dollars right now. You think of not just the prisons that were mentioned here, but the vast array of numerous forms of policing, the NSA, the things talked about by Edward Snowden in terms of the resources that are poured into ensuring the savage inequalities in this country. Then you think about how atomized this society is, more so out in places like the suburbs. Probably the only other societies that approach the atomization of Americans from each other might be in China or Russia — not coincidentally, being major powers themselves.

On the other hand, it wasn’t just George Floyd, it was Tamir Rice in 2014. I saw a number of the organizers because I knew they were talking to families of the deceased. You could see the PTSD in their eyes. It’s difficult, in those circumstances of violence and oppression, to continue on, but I’m convinced that many of those people will be back when there is another upsurge. One of the values of political organization is that it sustains people like us during the lower times. We read, we study, so we understand that we are part of not just one movement but a grand sweep of history and how people in different circumstances have not only managed to persist, but achieve gains. You think of what was done in the Great Depression in this country in circumstances that we can only begin to imagine: the deprivation, the lack of social programs. And yet people who were literally starving created the mass union movement.

I remember, during the height of the pandemic, just thinking, “they keep on patting on the back all these healthcare workers and so-called ‘essential workers.’ People are going to come back and say, ‘okay, now it’s our fucking turn.’” We’ve already begun to see that in places that none of us predicted: Starbucks, Amazon, etc. It’s got a long way to go, given the utter devastation of the union movement in this country, but that’s the beginnings of the sort of solidarity that we saw at the heart of the BLM movement, where activists were helping each other out. There were of course all sorts of divisions and infighting in that movement as there are in every social movement. Any reading of the Civil Rights Movement of the early 1960s shows it wasn’t all hunky-dory, everyone skipping off to the promised land. There were bitter fights and all sorts of sectarianism and nastiness. But there’s also a lot of human kindness for each other and selfless solidarity that we saw in places like Iran in 1979, with the oil workers going out on strike and the massive women’s movement of that era. The principled folks will be back. Those who went onto develop careers — good riddance to them. But the vast majority of people in this country continue to be screwed, especially black and other oppressed people. The system can’t help but create its own gravediggers.

TC: On whether it is a dead movement or a first stage, we gotta decide. That’s a question for us. The ideas of abolition — the political values and strategy — were all intentionally co-developed with organizers and theorists. You can trace the lineage of prison abolitionism as a set of ideas developed over time through thinkers like Ruthie Gilmore and Dylan Rodríguez. Likewise, you can trace critical resistance’s lineage as a formation on the west coast. If anything, these lineages are symptomatic of how far we can popularize radical demands and ideas and how they can spark when they resonate with a mass sensibility, tendency, or experience. When these ruptures happen, the status quo, in terms of ideology and culture, gets mushy. That’s our opportunity to popularize and collectively raise the elements of our understanding. We have to deepen our understanding further as conflict arises. Part of that is understanding police violence as militarism — as domestic iterations of militarism and low-intensity warfare — and that we’re up against massive propaganda machines. We talk about the U.S. military industrial complex and Psychological Operations division’s dedication to propaganda. Why are there so many local newspapers and publications that are so popular when the only thing they cover is crime? It’s because they have entire agencies and corporate businesses that are popularizing these narratives of crime, punishment, and disposability. We have to have forces, communications operations, and propaganda work to combat and counter that.

A lot of the tensions in the conversation about abolition are playing themselves out similarly in the world right now. In the context of the Left, of which we are part, some want to abolish the police, or the carceral state, because, from a Marxist perspective, special bodies of armed men constitute the capitalist state. Lenin’s TheState and Revolution was brought up, in which the state is not considered neutral. Rather, it’s in the service of the bourgeoisie, capital, etc. Another contemporary Leftist argument is that of carceral capitalism, which is viewed as the Reagan neoliberal era coming into its own. This leads to the disproportionate incarceration of black people, particularly young black men, and thus carceral capitalism is something that needs to be fought against specifically. Those are the two contexts for that argument. Comrades CJ and Naomi raised the good point that abolitionists don’t take into consideration the regular working class today, who may be disproportionate victims of incarceration. It was helpfully pointed out that because crime disproportionately affects working-class communities, they’re the most ardent defenders of law and order. If one were trying to reconstitute a mass Leftist politics nowadays, one would alienate them by saying, “abolish the police.” This conflict is refracted within mainstream politics in the issue of electoral constituencies within the Democratic Party and how different communities will vote in upcoming elections. Can the Democratic Party still have the working class vote for them, or will the working class become increasingly Republican? The question is not, “how do you distinguish yourself from a Democrat?” The more productive question regards the issue of consonance of disagreements within the Left and within the Democratic Party at large. Is this merely a coincidence? If it's not, what is the historical depth and extent of this consonance?

CM: I don't know what I can say about electoral constituencies within the Democratic Party, but it seems like the old questions of reform or revolution and materialism or idealism, which go as far back as our tradition.

TC: You can look at that and ask, “why is it that the communities most disproportionately harmed by these systems and structures still support some of these structures?” And you can look at that from a perspective of, “what's wrong with the working class?” Or you can look at how deeply entrenched the divestment of communities is and how there are so few options. We are not the Left of Brazil. We do not have the social structures and infrastructure to support communities, where they can live better than they do under the mediocre U.S. state. It’s an indictment of the Left more broadly, of our capacity to support and meet the needs of our communities, and not so much an indictment of the working class.

We should not speak in generalizations about different communities — that’s just unscientific. Because I know lots of people that are experienced and against the police, I can try to assess that through generational lenses. You can assess that by looking at how consciousness is being shaped by culture. The point is that reality needs to be contested, that people are forced in an abusive position to rely on the state. It is our job to try to meet those needs ourselves such that people are not forced to rely on a violent apparatus and system. That’s why abolition is so important, specifically because of all the other tendencies that came out in addition to it. If we’re trying to make the prisons obsolete, we also have to come up with frameworks — interpersonal, relational, social frameworks — on how to address harm in our communities. I’ve been a part of several community-accountability processes, where we’re trying to navigate these practical questions so that we can deal with harm without relying on the culture of disposability and violence of the state. We have to be able to do that work; otherwise, it’s an uphill battle.

NC: I’ll make a comment about the Democratic Party. It’s in crisis, as is the Republican Party, because none of them have any answers to the problems that face us. None of them can solve the basic underlying problems of the capitalist system. A good chunk of the Left is in the Democratic Party, and the Left wing of the Democratic Party is pushing identity politics — that everything revolves around identity constituencies — which is tearing up the Democrats. It’s a poison within the working-class movement to be defining everybody by their identity as opposed to talking about classes and building class solidarity, etc. One of the other things that especially the Left wing of the Democratic Party promotes today is a dependence on the capitalist state, e.g., forms of welfare. I’ll give you a concrete example: in Illinois, one of the points that’s going to be on the ballot is Amendment 1, which is put forward as a workers’ rights amendment. We’re taking a position of not voting for or against it, because it does absolutely nothing. Rights aren’t given to us by the state; we fight for and win them. This reinforces a dependence on the state and the Democratic Party to protect our rights as opposed to us fighting and organizing. What we need as opposed to dependency and welfare is a fight, especially led by the labor movement, for jobs. There’s lots of people out of work. They say unemployment numbers are very low, but the reality is that there’s a smaller percentage of people working than there has been in a long time. Many of the jobs that do exist necessitate crazy overtime or schedules that make it impossible to spend time with family. That’s what a lot of labor battles have been fought over, and it’s at the heart of the issues in the rail-contract negotiations. These kinds of fights — for jobs, to shorten the workweek with no cut in pay, to spread work around and take it out of the boss’s profits, the fight for cost-of-living raises — these things that help to strengthen the working class are what we have to fight for.

AT: On disagreements on the Left regarding abolition — first you have to ask, “who is the Left?” If we’re talking about organized Left party formations of one sort or another, unfortunately we’re irrelevant at this point in this country of 300+ million people. I wish it were different, but that’s the sad truth. The issue of how working-class people feel about policing is not just racial; it's not just class-based; it's also generational. A common experience in the city of Chicago — I see this from all these wrongful conviction cases: cops will pick up a young person in one neighborhood, and if they don’t get what they want from them, they drop them off in another gang’s territory. They let the gang wars do their fight for them, basically subcontracting the violence in that respect. They get people from rival gangs to testify against each other about stuff so they can “solve the murders.” This is so common in the Reynaldo Guevara cases. “Hero cop solves dozens of murders,” and now we’re finding out, after decades of wrongful convictions, that they never caught anyone who did the murders.

I watched a good PBS documentary over and over again about the fall of Reconstruction. People probably know the history in broad outlines, about how the Republicans were the party against slavery and had a modicum of support for black people. The moment the Panic of 1873 hit, the Republicans, who had been in power for decades as the party against racist oppression, cut loose black Americans and fed them to the wolves. The ensuing decades from the 1870s to the 1920s were probably the worst decades of racist violence in history, even worse than the period following the Civil War. The Democrats, who have proclaimed that they are for working-class people and have been riding on their coattails for decades, are getting their comeuppance right now with the Republican Party falsely claiming that they're the party for the common people. The moment that the economy hits the skids, you have an eruption of racist violence, and you have the growth of Proud Boys-type groups, etc. Whoever wins on November 8 and in coming years, we’re going to have an ugly time, because both parties have shown themselves to be bankrupt in terms of meeting the needs of working-class people, and it’s clearly been a ticket to power to play on racism, nativism, and anti-LGBTQ bigotry. The Republicans are surging right now, and the Democrats have no one to blame but themselves, because they have sold out working-class people for so many decades, beginning with the neoliberalism of Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton.

I’ll repeat the end of the question. The discussion of abolition’s tensions across racial lines is being posed against tensions across class lines. You also see an analogue in the discussions amongst electoral constituencies in the Democratic Party, and also the Republicans. Is it merely a coincidence at this moment in 2022 that the same tensions are playing out amongst the Left and also amongst the Democrats in their electoral constituencies? How far back in history might this similarity in tensions go? CJ came the closest to addressing this when he pointed to Rosa Luxemburg’s “Reform or Revolution” (1900), but maybe there are different moments from the 20th century that come to your minds as a precedence for the moment of consonance between tensions within the Democrats and those on the Left.

Moderator: By coincidence, do you mean divisions over race versus class within the Left and within the Democratic Party?

Yes.

AT: Class is the identity that never speaks its name, but then you have Leftists who dismiss the thoroughly race-driven narrative that so much of our country was built on in terms of the extirpation of Native Americans, and slavery, which played a pivotal role in the development of American capitalism. Every time I think that identity politics has run its course because you have a Clarence Thomas or whatever, someone comes up and says that race is irrelevant to the development of American capitalism. Here we go again: let’s play a part in the divide and conquer! Capitalism’s main goal is to make money and to do it by any means necessary. Race has clearly been pivotal to dividing American workers, going back to the steel strikes in the early part of the last century. It’s been the albatross on the working class in the U.S. South, and to diminish racism as a powerful force buttressing American capitalism is just foolish. The early Socialist Party in the U.S. was a disaster area for that. Eugene V. Debs, for all his many merits, was the one that said that the Socialist Party has got nothing special to offer black people. It was only the intervention of the Third International in the early American Communist Party that began to turn some of that around.

TC: I’m not sure. If you don’t understand reparations as a communist measure, then I’m not interested in that platform. If you don’t understand this as a part of your analysis of racial capitalism and the importance of resource distribution in this country, that’s where we have issues. We have to understand how these things are integrated and also how the state and capital will try to mess with that and take advantage of these different ideas to pit us against each other.

NC: I’ll just make another plug for Barnes’s Malcolm X. It’s got a wonderful section on what you were just alluding to: what the Bolshevik Revolution taught about the place of the national question and how intertwined the fight against national oppression is with the fight of the working class for power with a concrete application to the U.S. It connects to the biggest national question in the U.S., which is the oppression of African Americans, although the national question comes up in different forms all over the world. A lot of the Left is within the Democratic Party, and a lot of the debates on the Left play out in one form or another there, e.g., Bernie Sanders. Bernie Sanders and the Democratic Socialists of America are deep into the Democratic Party and have the idea, which is harmful to the working class, that you can somehow turn the Democratic Party into something that it’s not.

CM: If you asked me that question four more times, I still wouldn’t get it, so I'll leave it there.

Given this current moment of democratic backsliding in the U.S. and the rapid polarization of the Right, how do you feel that affects our efforts in regards to socialist revolution and abolition?

Rather than keeping your eye on the Democratic Party and the Left groups within it, it’s more important to keep your eye on what the working class is doing. There’s no strike wave in this country right now, but there are some important labor struggles. During the pandemic there was a wave of nurses’ strikes, despite the fact that they were painted as evil people with reactions like, “how could you strike when there's a COVID pandemic?” One of the nurses’ slogans was, “they called us heroes, and they treat us like zeros.” They demanded wage increases, better hours, and a better proportion of nurses to patients for safety’s sake. Today, there are 1,100 underground coal miners in Alabama on strike. If you look at them, you'll get a better picture of what the possibilities are, because it’s true: imperialism is strong, and nuclear weapons could destroy us if they are driven to that. Now we give workers a chance at taking political power. The same thing goes with George Floyd: there was no dual power at any point during the protests. There was dual power for a couple of years in Cuba, where the rebel army set up 400 schools and medical clinics in the mountains and areas that they controlled. That is the kind of thing that we have to look forward to. And in the meanwhile, yes, we’ll see a lot of workers’s solidarity.

Timmy, I’m interested in your work with children and how that has shaped up. I also wanted to point out that all four of you have an idealistic mindset; you all — we all have hope for the future. That’s why I wanted to ask the question about kids and how that works.

TC: On backsliding and the rise of the Right, we’re already seeing re-entrenchment of the neoliberal status quo, expansion of the carceral apparatus, liberals supporting further criminalization, policing, and imprisonment. We have to resist that and call out the neoliberal status quo as white supremacist fascism. It looks different than January 6, as one moment in time. That needs to be militantly called out and opposed. I have not worked organizing unions, but I do have lots of comrades and friends who have — mostly people of color. I have heard stories about racism within the labor movement of the Left. As the Right has increased, I’ve seen segments of the Left trying to make appeals to racism: “but they’re workers” as opposed to, “Yes, class is happening right now, and this is risking further white supremacy and deepening racism and needs to be militantly called out.”

To the question around youth, I work with a lot of young people and they give me the most hope in terms of where folks are at politically, engaging in ideological struggle with one another. Because of the development of the internet and social media, access to political education — it’s like we’re in a cyclone in terms of the political education happening among young people, which has scary threats but also amazing possibilities. That gives me hope and more energy to fight climate change, because we messed that up. I’m saying “we” as in, so many generations of people.

AT: In response to the question about Democratic Party backsliding, and the effect on building not just socialism but our movements in general, we’ve been down this road many times before in this time of year during the election cycle. What we’re seeing this year is, “you’ve got January 6 and Proud Boys? We’re all you’ve got. There’s no place else to go.” That’s the Democratic Party response: “We’re gonna give you the same old shit that we’ve been giving for the last several decades, or you can have the Proud Boys. That’s your choice.” I wonder why the electorate is not super enthused within the Democratic base right now, and why they’re losing out to the Republicans who are motivated to “Make America Great Again” or whatever the fuck they call it. To the extent that the Left depends on the Democrats, we weaken ourselves.

By “democratic backsliding” I meant the push of the Republican Party towards authoritarianism and potentially getting rid of our democracy.

AT: The Democrats frankly screw working class people decade after decade. There’s a great book called The Fall of Wisconsin[5] which I strongly recommend; I picked it up on a lark a few years ago. It’s about the decades’ worth of Democratic Party promises to unions and others about how, “we’re gonna do something about the failings of the family farm,” blah blah blah. “We’re gonna do something about the loss of union jobs, we’re going to end NAFTA, we’re gonna bring in card check” — all promises the Democrats have been making for decades. The statements of union activists saying, “my own members, who generally would support me and respect me, see what these yahoos do when they get into office or stay in office, and they get betrayed over and over again.” If the choice is between the pre-Trump status quo and the Proud Boys yahoos, it’s scary. What’s happening to the Voting Rights Act right now? The destruction of one of the central pillars of the early 1960s Civil Rights Movement. There has been a decades-long war on all the gains of the late 60s and 70s. In the Supreme Court — if you think the last term wasn’t bad enough — not only do we have that, we have something called 303 Creative v. Elanus, which, if the court gets its way — and it seems very probable that they will — will say that LGBTQ people will not have equal access to public accommodations. LGBTQ people are not a protected class in the Supreme Court’s rulings so far, but if you take away equal access to public accommodations for one group, it’s a risk for all groups. That was another big pillar of the Civil Rights Movement. You look at how we got this court: it was none other than Senator Biden who oversaw the hearings that slammed Anita Hill and brought us Clarence Thomas. This is a bipartisan attack on working-class living standards, and every time the Democrats thought they were gonna lose an election they moved to the Right. That was Bill Clinton’s approach: ending welfare as we know it, bringing in the Defense of Marriage Act, etc. They voted for the Hyde Amendment, limiting abortion rights for poor and black women. This is something that they have acceded to continually, moving the whole train of American politics to the Right over the past four decades, to the point where now the Republicans, so as to distinguish themselves, go even further to the Right, flirting with neo-fascism. But it has been a bipartisan move. In every single election cycle over the last half century the terms of the debate have moved further to the Right, and the Democrats have been part of that. It’s scary what’s happening in terms of election denialists and voting rights being under the gun, but the Democrats aren’t going to save us from this. That’s the sad reality.