Afghanistan: After 20 and 40 years

Chris Cutrone

Platypus Review 139 |September 2021

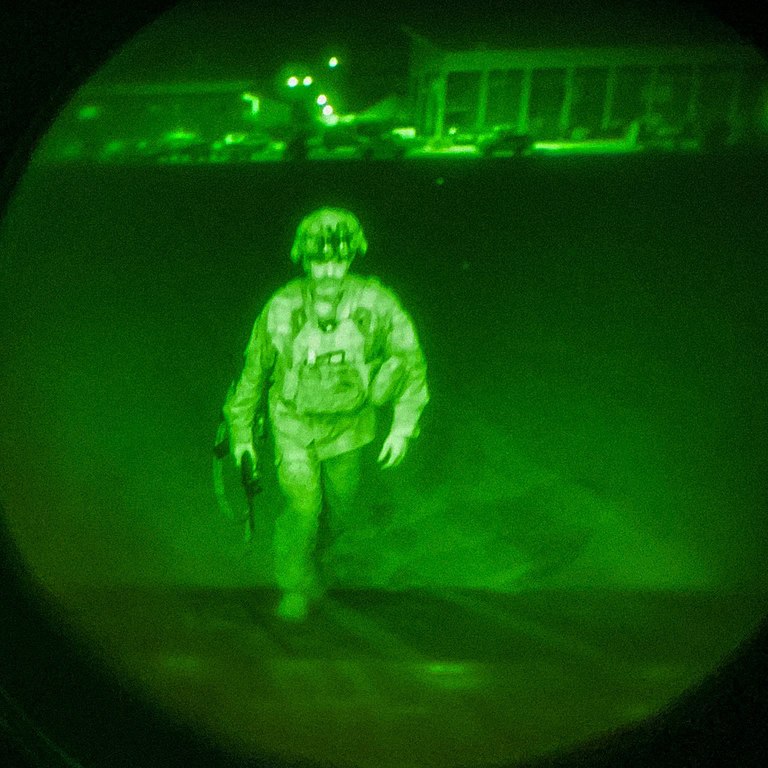

20 years

AFGHANISTAN WAS INTENDED BY THE U.S. in the 1980s to be the Soviet Union’s Vietnam War. But it is the United States today that is experiencing a second Fall of Saigon in Kabul. If the Great Recession was the historic crisis of neoliberalism, then the U.S. loss of Afghanistan to the return of the Taliban marks the definitive crisis and terminus of neoconservatism. John Bolton ran screaming bloody murder when fired by Donald Trump for resisting ending the Afghanistan war, but it is Joe Biden who now rules over the U.S. withdrawal. This is not some end to U.S. global hegemony — no more than Vietnam was.

Fred Halliday asked after the 9/11 terror attacks against the U.S., “Who is responsible?,” and answered that it was the U.S. itself, along with its allies Saudi Arabia, et al. — not in the literal sense of 9/11 Truthers, but rather in the profounder way that the U.S. nurtured radical Islamist terrorism in Afghanistan against the USSR and its local secular nationalist Afghan allies in the 1970s and 80s.[1] But the chickens coming home to roost were not Osama bin Laden’s al Qaeda but rather the Left itself. It was the legacy of the 20th-century Left whose price was to be paid now. There is an exacting cost to history.

The Millennial Left that was born in dissent from the 21st-century U.S.-led War on Terror has 20 years later seen a certain end to the endless wars that accompanied nearly all their conscious political lives. With its passing will come the dread and anxiety of a missing object for their fears. The problem is that they did not overcome the war in Afghanistan any more than the 1960s New Left generation stopped the Vietnam War. But they are liable to mistake historical transition for their own accomplishment. They never clarified what the war really meant and so will be confused now about its ending. Likely they will repress even awareness of this, as historical amnesia inevitably sets in. The roots for this are in the ways they were misled in their discontents from the start. The hopes and fears about the supposed decline of the U.S. are really the anxious dread of the long, slow disappearance of the Left. It means the foreclosing of hope yet again, as has happened successively several times since the 1960s: in the late 1970s; by Generation X in the 1980s–90s; and again by the Millennial Left in their experience from the 2000s–10s. The death of the Millennial Left has revealed its original stillborn character. It began with the anti-war movement, which ended promptly with Obama’s election at the end of the George W. Bush Administration. The logic of the anti-war movement — protesting Bush — led to an inevitable dead end.

Though it could claim victory now more than a score years later, did the anti-war movement or the capitalist elections to which it was tied make a difference? Biden’s withdrawal is met with embarrassed (or at least perplexed) silence by the “anti-imperialist” Left, such as it remains.

Obama promised an end to the wars but continued them; Trump seemed bellicose but wound down the wars he inherited and was the peace President Obama promised to be; now it is Obama’s former Vice President Biden who is fulfilling Obama’s original promises, but with ambiguous results — and ambivalently for the Left. The unpopularity of the wars has played into Trumpist patriotism more successfully than into a Democrat anti-war electorate, despite or rather because of the Bernie Sanders campaign in 2016, some of whose voters turned out for Trump or at least failed to turn out for Hillary Clinton, the staunchly pro-war candidate. Samantha Power, Obama’s National Security Councilor, was proud to proclaim that the Obama Administration had to abandon its intention to change and instead yielded to the “wisdom of continuity in U.S. foreign policy,” warning that Trump was incapable of learning such a lesson. But, recalling Nixon’s “secret plan” to end the war in 1968 and Henry Kissinger’s Nobel Peace Prize in 1973, Trump fulfilled his promises — to the constant consternation of the Left.

The Millennial moment

As a generation the Millennials were raised on New Left pedagogy such as Howard Zinn’s People’s History of the United States (1980), which taught them that America was built on colonial violence, slavery and genocide. This led them to believe that the War on Terror was a continuation of this history. But this was fundamentally wrong about both the past and the present realities of American history, especially its unique and different role in world history, which Zinn and his cohort sought assiduously to deny as alleged pernicious “American exceptionalism” and nationalist chauvinism. It was a lie from the start.

Ward Churchill said that if Native Americans had been able to they would have conducted the 9/11 attacks to stop their historic devastation by colonists from Europe. But it’s unclear that 9/11 did anything at all to stop or even temper imperial capital’s domination of the Muslim world. Indeed, it led not only to the invasion and occupation of Afghanistan but wider military engagement in Iraq and beyond. — In any case the entire War on Terror stemming from 9/11 and beginning in Afghanistan was a self-inflicted wound the U.S. could afford to suffer. Don’t expect any fundamental changes in geopolitics to result from it.

Noam Chomsky said that the U.S. won the Vietnam War: Despite not preventing takeover by the Communists, the U.S. had nonetheless sent the message that opposition will be punished severely. No doubt the Taliban learned some bitter lessons from their toppling 20 years ago for harboring al Qaeda and — who knows? — might end up in due time like Vietnam today depending on the U.S. for protection against more immediately threatening neighbors. U.S power was not shaken in Vietnam but only honed.

Adolph Reed wrote of the U.S. military operation against the Taliban and al Qaeda in Afghanistan that, while the Left opposes imperialist adventures, the working class wouldn’t understand protesting against the war and so had to be limited to pressuring for police action and not a crusade.[2] A pious wish, to be sure.

Doug Henwood, Liza Featherstone and Christian Parenti invoked Theodor Adorno’s critique of the 1960s New Left to interrogate the Afghanistan anti-war movement’s unthinking “activistism.”[3] This was yet another concession to the supposed “good war,” as Obama called it by contrast with the Iraq war.

Moishe Postone wrote of the historical situation of “helplessness” in which the Left had found itself in the era of the War on Terror.[4] There was no significant Left in Iraq or Afghanistan — even if the American Left had cared to find it. Though writing primarily about the Iraq war, Postone’s insight into the hopelessness of the Left is perhaps best exemplified by Afghanistan.

RAWA, the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan, despaired of the U.S. invasion in 2001 and expressed the agony of suffering decades of horrific atrocities under both Soviet and subsequent Islamist rule that they anticipated would continue with American occupation.[5]

The Spartacist League wrote of the “senile dementia of post-Marxism” and condemned the Left in the 2000s for preferring the bourgeoisies of “Auschwitz and Algeria” (Germany and France) to that of (the Americans of) “Hiroshima and Vietnam.”[6] But they soon abandoned even this tenuous insight; they nevertheless called for the victory of the Taliban against “U.S. imperialism.”

40 years

A generation earlier, the Spartacists had declared “Hail Red Army!” for the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan, and said it represented the “Russia Question point-blank,” arguing that there was a “class line” at stake in the war. (Also, the “Women Question.”) — Was the legacy of the Russian Revolution in jeopardy there?

But the USSR (as well as its Warsaw Pact Eastern European allies — also Yugoslavia) was not destroyed by the Mujahedeen nor by the U.S. under Reagan in the Second Cold War of the 1980s but by internal impasse and crisis which had become evident previously in the 1970s.

The Spartacists were painfully aware of the fragility of the bureaucracy in the USSR et al. and sought to challenge bureaucratic rule in the name of socialism by confronting the rulers in the USSR et al. with their own political claims to stand for socialism. It was an immanent critique of Stalinism according to its own values — and their evident self-contradictions.

In this sense the USSR’s military intervention in Afghanistan was an expression not of strength but rather weakness — vulnerability and susceptibility to failure and betrayal. One could perhaps make similar arguments about the U.S. in Afghanistan — or Vietnam — but this would stretch credulity and avoid the profound differences of the U.S. from the USSR’s overreach and political blunders. In either case there is not only tragedy but criminality. But any political estimations of culpability must judge the U.S. more criminal and the USSR more tragic in the balance. In any event the USSR’s crimes were really due to the crimes of the West — including the suppression or mere undermining of the struggle for socialism there.

What this raises is the old 20th-century Cold War divisions between the “First, Second and Third Worlds” — the capitalist core, the ostensibly “socialist” bloc and the postcolonial and other poor countries not strictly aligned with either of the first two. Whereas the Old Left (of Stalinism and Trotskyism alike) emphasized the plight of the Second World, the New Left (such as Maoism, decolonization/Third World Nationalist movements, etc.) emphasized the Third. But today — since the end of the Cold War in the 1980s — there are only the First and Third Worlds — and perhaps not even that distinction holds any longer — which changes the political and social framework of world-historical possibilities fundamentally.

“First Worldism”

The only potential cure for the plight of the Second and Third Worlds was socialist revolution in the First World. Second Worldists — Stalinists — avoided this truth, whereas Third Worldists forgot this entirely. But today the priority of the struggle for socialism in the First World has been made obvious by the failure of the separate struggles of both the Second and Third Worlds. — Notwithstanding China’s simultaneous status today as Third, Second and even First World in nature, i.e. as a global capitalist power that nevertheless remains inextricably dependent on others and contains deep poverty and which claims to be socialist and is ruled by ostensibly Marxist Communists. But there is no new Cold War between the U.S. and China nor is there an inter-imperialist rivalry between them: China is clearly a subordinate power to the U.S. in the global capitalist order no less than Europe and Russia are. And China will remain so for the foreseeable future. — But such considerations are actually secondary, and pose things in a backward way.

The future of socialism still hangs on the fortunes of its struggle in the U.S. — or lack thereof. This is the basic truth buried under a century following the failure of the original Marxist project in and after WWI.

So we continue to be haunted by the previous century’s concerns despite being clearly in a very different situation today. Especially the Left is oppressed by its own past as a nightmare weighing on the brain.

If the Spartacists were concerned about socialist betrayal, capitulation and liquidation to either the Soviet bureaucracy or to U.S. and other imperial capitalism, then ever since both the Soviet and U.S. invasions and occupations, the Left has been faced with the danger of capitulation to Islamism, whether of the Mujahedeen or Taliban. The roots for this were in the anti-war movement descended from the Vietnam War era and its “anti-imperialism” which led to Third Worldism.

The 1960s New Left protested against the Vietnam War. (Also, if to a lesser extent, against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia to stop the Prague Spring.) But by the time the USSR intervened in Afghanistan in 1979 to resolve a political crisis and stop reactionary Islamist insurgency against the friendly regime, the New Left mostly opposed the Soviet action, whether it be Trotskyists and social democrats such as the DSA Democratic Socialists of America out of anti-Stalinism or by Maoists against “Soviet imperialism.”

Analogizing Afghanistan to Vietnam in the imagination of the New Left was the picture of poor brown people attacked by white people wielding horrific mechanized armed forces. Even the helicopters terrorizing remote village countrysides from the air seemed to connect the wars in the popular as well as Left imagination. General Giap was still too modernist: Afghanistan was the first “postmodernist” war — the very definition of Donald Rumsfeld’s post-Vietnam “light warfare” doctrine — and remains so. It is fitting that after decades of facing IEDs it is Biden’s cadre of woke Democrats and militarists who have to entreat with the Taliban now — and will be happy to be permanently lost in translation. Trump spoke the Mullahs’ same sanctimonious Mafiosi language — if in Nixonian dialect — too fluently for comfort.

Reaching back to an earlier time, Fred Halliday said that Afghanistan represented the 1930s Spanish Civil War of the modern era, taking the side of the USSR and its allies, while his fellow New Left Review editor and the original “Street Fighting Man” of the 1960s, Tariq Ali, dissented and condemned the Soviets in Afghanistan, despite being a member of a Trotskyist tendency that supported them, however critically. Twenty years later, Ali condemned the U.S. as well for its military intervention in Afghanistan. At least Ali was consistent in his superior Muslim-Brahmin South Asian “solidarity.”

All this expressed the exhaustion and confusion of the New Left by the late 1970s. It still expresses the confusion and exhaustion of the Left today. What is confusing are the partial truths the Left expresses.

The Left is perhaps the most naively credulous audience — permanently stricken with the ugly naiveté of adolescence — gullible for any shameless political propaganda, and slapped upside the head so hard and so often by reality as to never quite stop reeling from one capitalist political crisis to the next. This has been true since the 1930s, when Stalin’s Soviet Union could never decide which way was up — or down — between FDR, Hitler and Churchill. But at least Stalin knew a “useful idiot” when he saw one.

Today there are nothing but idiots. — We are all useless idiots.

Present reality

If militaries are always stuck “fighting the last war” then what of the Left — since they never fought through anything to completion to begin with? At least today’s hashtag “activism” — by contrast with what Adorno in the 1960s called “pseudo-activity” in “pseudo-reality” — has the decency to never leave the bedroom and not bothering to pretend on the streets — even when it is on the street, its head is permanently checked-out online in a fever-dream mercifully shared by few. The Left is stuck in an imaginary past.

But there is nonetheless a reality — however remote or inconsequential for the Left. And that reality has changed between 1981 (1991) and 2021. But one such reality is that of unbroken U.S. rule geopolitically.

What was the Soviet goal in Afghanistan in the 1980s? To preserve its influence and prop up a rare ally in an area of strategic concern in the Cold War standoff with not only the U.S. but also the latter’s ally in Communist China.

What was the U.S. goal in Afghanistan in the 2000s–10s? To keep a lid on simmering geopolitical rivalries in a fragile hot-spot of regional conflict. Today as in 2001, Afghanistan is a zone of disorder that, as such, threatens its neighbors Russia, India, Pakistan, China, and Iran, all of whom have a hand in the war of the last 20 — or 40 — years that will not be fully settled but only exacerbated by the current Taliban takeover, which is likely to be temporary. — As of this writing, ISIS is already bucking the Taliban and setting off terror attacks, desperately attempting to draw the U.S. back into Afghanistan.

Perhaps China can help keep Pakistan’s favorite in power in Afghanistan as opposed to India and Russia — perhaps not. One thing is certain: The U.S. served as well as checked all of them in Afghanistan and was thus both welcome and unwelcome there to all. The U.S. will be missed.

Biden is right — as was Trump — that the U.S. has no national interest and never did in Afghanistan — but only an international one. Bill Clinton was happy to leave the Taliban alone in the 1990s. So would have George W. Bush if it hadn’t been for 9/11 which proved to be a very costly fit of absence of mind for the Taliban.

As with Vietnam, Afghanistan and the greater Muslim world was made to pay a steep price for slighting let alone defying the U.S. to any extent whatsoever. The message was heard — and it has been heeded.

The future belongs not to al Qaeda or ISIS but perhaps to the Taliban, which are not so different from Wahhabist Saudi Arabia. — The Islamic Republic of Iran would be more tolerable to the region and hence to the world if it were Sunni and not Shia. But accidents of history have ways of correcting themselves.

Trump was right to step out of Syria and let the chips fall as they may between Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Iran, balanced as they are against each other, and seeking to parlay this into a gesture of opening to Iran, perhaps even prying the latter away from Russia in the process. He sought to repeat this détente in Afghanistan, leveraging it to keep all regional geopolitical competitors beholden to the U.S. as an essential third party in the process. — The danger with Biden is that he will squander the negotiating position of trilateralism and turn American withdrawal into a gaping hole into which more than Afghanistan might collapse. But that void — the absence of socialism that is capitalism — has been there for a long time: The world was not stable before 9/11, and indeed was not as stable when the U.S. inaugurated its global rule after WWII as has been misremembered by the Boomers and their children.

The bottom line is that of course none of this has anything to do with the Left or socialism but is just the realpolitik of capitalism.

Post-Millennial future

The Left, in living for so long under the shadow of the Cold War and Vietnam, cannot acknowledge let alone recognize properly that the U.S. is not the source but only the central — and indispensable — actor in the politics of global capitalism. Anti-Americanism is a sham. The U.S. has to balance Europe, Russia and China as well as India, the rest of Asia, the Middle East and Latin America — as well as increasingly Africa — in the more or less global chaos of world capitalism. It is an unenviable task. And it is one that Obama and Biden were happy to leave to the professional bureaucrats and Trump was foolish enough to try his hand at cooling — for which he was roundly condemned for threatening to inflame.

The mythology of the anti-war movement going back to Vietnam, that unpopular wars rejuvenate the Left, has been dealt a blow by Afghanistan: Does defeat or failure of U.S. imperialist adventures radicalize politics in a Left-wing direction? — What is it the Left wanted that it seems to have gotten now, however belatedly?

Trump drew down the Forever Wars and started no new ones. Wars as always in capitalism are the result not so much of design but of miscalculated risks in political gambles. Trump’s was perhaps the safest of them all in that he jealously guarded the cache of U.S. power, both soft and hard — but he couldn’t horde it but only leverage it on credit, as he had done his entire business career. Now the American brand is tarnished — but was already so when Trump acquired it. Will it be bankrupted? Not really. The U.S. of all things in global capitalism really is “too big to fail.”

Trump was good at turning bankruptcy into leverage against his creditors and perhaps was trying to do the same with U.S. policy in his Presidency. So what was the U.S. policy such that it could be claimed to have failed and in danger of going bankrupt? That is the essential question posed by Afghanistan. But first it is important to spell out what it is not: It is not that of the U.S. as a national power as against others.

Neither a new Cold War nor a new inter-imperialist war is likely, despite what the Left in its nihilism might want. Such desire is just an empty abdication of the task of socialism in the U.S. — now as before.

There is no real rivalry that the U.S. faces or even any actual challenges to its hegemonic role: No one desires let alone could possibly play the part of the U.S. in the latter’s absence. Not the death metal white tribes in the Epcot Center of Europe, nor the eternal Steppenwolves of the Golden Horde, nor the Yellow Peril of Communist-trained pandas in the 2,000-year Mandate of Heaven.

But we are living in capitalism not the Khanate. Afghanistan is no longer the “graveyard of empires” but just someplace best avoided by sensible people and left by the wayside on the Silk Road (today, the Belt and Road Initiative) of history. There are other such places — many (for instance the Congo) — whose only difference is that one doesn’t hear their names. The American and Soviet mistake was not to forget but rather to ever learn it. (The afterimage of Roxana and her scorned scion fading in the distance,) Afghanistan will fall back now into its rightful oblivion in the dust of Alexandrian Bactria. |P

Further reading:

Chris Cutrone, “Iraq and the election: The fog of anti-war politics,” Platypus Review (October 2008), available online at: <https://platypus1917.org/2008/10/01/iraq-and-the-election-the-fog-of-anti-war-politics/>.

Cutrone, “Internationalism fails,” PR 60 (October 2013), at: <https://platypus1917.org/2013/10/01/internationalism-fails/>.

Cutrone, “1914 in the history of Marxism,” PR 66 (May 2014), at: <https://platypus1917.org/2014/05/06/1914-history-marxism/>.

[1] Available online at: <https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/who-is-responsible-interview-with-fred-halliday/>.

[2] Reported in Rick Perlstein, “Left Falls Apart as Center Holds,” Observer, October 22, 2001, online at: <https://observer.com/2001/10/left-falls-apart-as-center-holds/>.

[3] At: <https://www.leftbusinessobserver.com/Action.html>.

[4] “History and helplessness,” Public Culture 18.1 (Winter 2006), 93-110, online at: <https://read.dukeupress.edu/public-culture/article-abstract/18/1/93/31815/History-and-Helplessness-Mass-Mobilization-and/>.

[5] See statement of October 11, 2001, online at: <http://www..rawa.org/us-strikes.htm>.

[6] Spartacist 59 (Spring 2006), online at: <https://spartacist.org/english/esp/59/empire.html>.