The case for a Marxist intersectionality: Class reductionism, chauvinism, and a critique of D. M. Faes on transgender liberation

Bennett Shoop

Platypus Review 116 | May 2019

IN A RECENT ARTICLE on the transgender liberation movement, D. M. Faes mobilizes a critique of the electoral strategies of the homo/transnormative political struggle. Faes’s critique reprimands the methods of LGBTQ+ activists on the Left for pursuing social change through “existing civic institutions and the Democratic Party.”[1] He claims that the effect of such a strategy is ultimately “the political miseducation of the youth they aim to enlist to such a cause.”[2] While I in no way support the primacy of electoral politics as an emancipatory strategy, I cannot help but disagree with this perspective for ignoring the fact that people suffering from oppression inevitably need to aim for reform in some cases in order to alleviate the pains of marginalization. Furthermore, Faes’s claim that “[s]ocialism…could not offer anything particular to any group or any particular creed; it could only offer the emancipation of all humanity”[3] is a class-reductionist oversimplification of the fight for socialism and revolution. In leveling this critique, I attempt to argue that not only is it important for socialist organizations to prioritize and center the struggles of those who are not oppressed merely on the basis of class, but that a failure to do so not only alienates marginalized groups from the general struggle for socialism and liberation but could lead to a monolithic, narrow, and chauvinistic socialist movement.

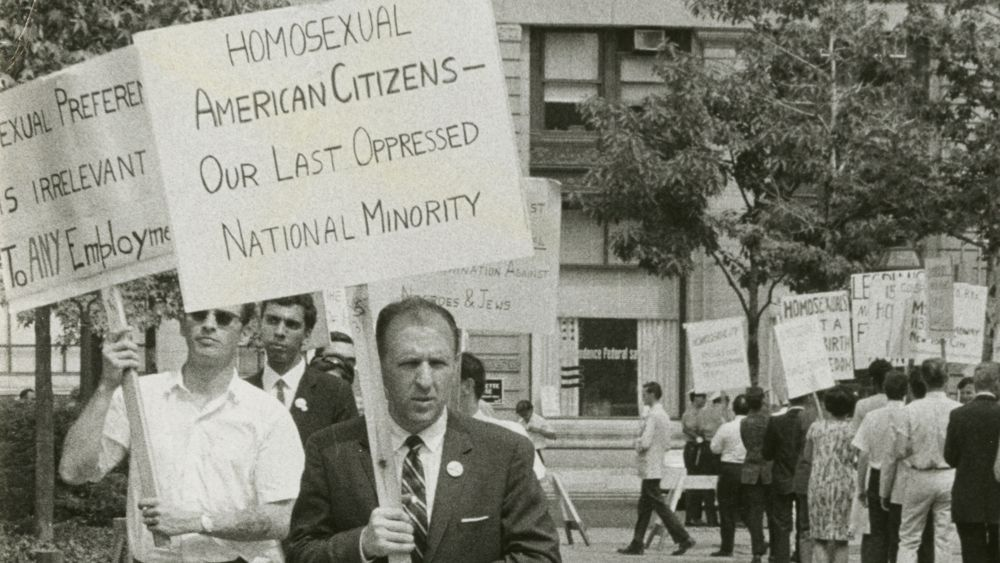

Firstly, Faes’s analysis of the modern LGBTQ+ liberation movement shows a misunderstanding of the history of the essential ties of LGBTQ+ liberation to larger socialist projects. One such example is the Mattachine Society, the first gay liberation organization to achieve some kind of widespread success and notoriety, which was founded on Marxist principles by former members of the Communist Party of the United States of America in the 1950s.[4] The founder, Harry Hay, was a communist, a teacher of Marxist theory, and the first person to declare that gay people are an oppressed minority.[5] Hay utilized Joseph Stalin’s theorization of the nation to declare that gay people constituted, not a nation, but a minority within America defined by several of the characteristics that Stalin had outlined as constituting a nation.[6] The CPUSA had similarly expanded Stalin’s theory to describe Black Americans as a minority group within a nation; Hay simply extended the Party’s resolution in the Mattachine Society to include gay and lesbian people.[7] While this organization was specifically designed to address the needs of gay people, this was not an example of “weakness in the pursuit of freedom…glossed over with the luster of identity” or of activists who “hold their beneficiaries politically hostage to the existing dynamics of the Democratic Party” as Faes charges the modern LGBTQ+ movement with.[8] This focus on gay identity was a necessity, based on the fact that one could not be gay in the CPUSA at the time. In an era full of the persecution of homosexuality as a result of its illegality, gay men and women could not simply ignore their specific oppressions in favor of the ultimate goal of socialism.[9] Furthermore, though their organization did focus specifically on gay liberation, they were committed to an understanding of the co-constitutive nature of all oppression under the causal oppression of capitalism[10] and sought to place the homosexual liberation movement within the broader socialist struggle.

Another such example is the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), whose work was also dedicated to the larger socialist project. In the “Statement of Purpose” of the Los Angeles GLF branch, they state: “[w]e are in total opposition to America’s white racism, to poverty, hunger…we oppose the rich getting richer, the poor getting poorer, and are in total opposition to wars of aggression and imperialism, whoever pursues them.”[11] Here, again, is an example of an LGBTQ+ liberation organization whose principles are founded on the socialist cause and who seek to form a popular movement for the general struggle against oppression. Faes’s frankly ahistorical condemnation of the LGBTQ+ movement as a movement in opposition to the principles and tactics of the Left is a misplaced and alienating claim. If his goal is to unite different groups in the general struggle for socialism, then his tactics are greatly ineffective. Looking beyond his oversight of the rich history of communist-aligned LGBTQ+ liberation movements, his language is outdated and offensive to many people in the trans community, namely the terms “transvestite” and “transvestism.” If socialists are to truly create a unified and broad movement, we must make it a primary concern to address the needs of different marginalized communities; hence the need for what could be called a Marxist intersectionality.

As has been seen in dozens and dozens of cases historically, the white/male left (while often not without good intentions) has repeatedly alienated and marginalized people of color, women, LGBTQ+ people, and others by their sole focus on class struggle and their relegation of anti-racist, anti-sexist, etc. struggles to the margins of socialist organizing. In her collection of interviews with the Combahee River Collective, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor details that in many of the founding women’s stories, their alienation from the white/male left was the primary reason they had to form their own organization. One of the founding members, Demita Frazier, recalls the ostracizing of her specific needs as a Black, working class, lesbian woman in socialist movements. She explains that she “had investigated the Youth Socialist Alliance (YSA), but it was too white, and too problematic on other levels.”[12] Furthermore, she explains that she “never ever…would join an organization that did not have a feminist and a Black feminist analysis.”[13] Another founding member named Beverly Smith explains that a lot of people’s perception of socialism is that “if someone’s a socialist, it’s only about economics. It’s only about work. It’s only about material conditions. It’s only about capitalism. And it’s often only about men.”[14] These women, however, were all self-identified Marxists and unequivocally believed in the struggle for socialism. If they felt so alienated by the white and male chauvinism on the Left, then that is an issue that needs to be addressed by socialist organizers, not by those who have been alienated. Another example of this alienation is provided by Marxist feminist scholar and activist Silvia Federici, who discusses the way in which the white/male left consistently denigrated not just the Wages for Housework movement that she was involved in, but also women’s anti-capitalist struggle and socialist feminism generally.[15] Instead of critiquing the fracturing of women, people of color, and LGBTQ+ people away from the general socialist struggle, perhaps the problem should be rephrased as “how can we as socialists appeal to different marginalized communities and encourage them to engage in socialist politics?”

While many Marxists have critiqued the usage of intersectionality in liberal frameworks and its use in mainstream and non-Marxist political organizing, the term, as initially envisioned, still has a lot to offer in answering this question. The previously mentioned Combahee River Collective is often credited with applying intersectionality before the official term was coined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in the 1990s. The Combahee River Collective defined their political outlook as “struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and [seeing] as our particular task the development of integrated analysis based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking.”[16] This is by no means whatsoever a position incompatible with Marxism. In fact, their position is directly an elaboration of Marx, but with one key intervention. They state that “[a]lthough we are in essential agreement with Marx’s theory…we know that his analysis must be extended further in order for us to understand our specific economic situation as Black women.”[17] This idea would become a foundational principle within Black Marxist feminism, because they were “not convinced…that a socialist revolution that is not also a feminist and antiracist revolution will guarantee our liberation.”[18] This critique of Marx is not a rejection of his ideas, of socialism, or of the root of racism, sexism, etc. being found in capitalism, but is the important intervention that Marx’s theories must be elaborated upon to understand the different features of different experiences of oppression that happen under a racist, sexist, and homophobic capitalist society.

Furthermore, intersectionality as framework is not at all in opposition to the Marxist frameworks of dialectical and historical materialism. Vladimir Ilyich Lenin defines dialectical materialism as “the doctrine of developments in its fullest and deepest forms, free of one-sidedness—the doctrine of the relativity of human knowledge, which provides us with a reflection of eternally developing matter.”[19] Lenin’s definition, his understanding of the importance of relativity and of the all-encompassing possibilities of dialectical materialism is echoed by intersectionality scholars. Patricia Hill Collins and Sirma Bilge assert that “[i]ntersectionality is a way of understanding and analyzing the complexity in the world, in people, and in human experience” and that it is an “analytical tool that sheds light on the complexity of people’s lives within an equally complex social structure.”[20] Intersectionality illustrates that “the events and conditions of social and political life…[are] not shaped by any one factor. Rather…many factors that [work] together in diverse and mutually influencing ways.”[21] They then describe that intersectionality has “six core ideas that appear and reappear when people use intersectionality as an analytic tool: inequality, relationality, power, social context, complexity, and social justice.”[22] These are not only all things that can, and should, be taken into account within the framework of dialectical and historical materialism, but also things that can, and should, be core ideas of any Marxist analysis. While the particularity of terms like social justice versus socialism/liberation might be contested, the main idea behind intersectionality as a tool for structural analysis and critique (as it was intended) is very much a helpful tool for Marxists. Black feminist theory, from which intersectionality originates, is not a reformist, counterrevolutionary ideology like bourgeois, white feminism, but a primarily anti-capitalist theory, and Barbara Smith even makes sure to emphasize that “[a]nticapitalism is what gives it the sharpness, the edge, the thoroughness, the revolutionary potential.”[23] This Black feminist theory of intersectionality is not, then, as some have charged, a counterrevolutionary dilution of Marxism, but provides an important advancement in the ability of Marxist theory to understand the specific material conditions for differently marginalized groups. As the Combahee River Collective’s statement argues, “[i]f Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.”[24] This is not just identity politics, either. This is the understanding that not only are Black women multiply oppressed by capitalism, racism, sexism, etc., but that within any system of oppression, Black women are at the bottom of the hierarchy and hence experience the harshest material conditions of class oppression, of racism, of sexism. This understanding also illustrates that Black women are in need of specific attention to their issues by socialist organizing, and that the theory of intersectionality proves that all sorts of differently marginalized groups experience oppression under capitalism in different ways, and therefore should not be accused of identity politics or divisive sentiments when they point out the particularities of their struggles against capitalism.

So, in returning to a critique of Faes’s arguments, I think the importance of not relegating identity-based oppressions to an afterthought of socialist organizing creates a necessity for incorporating an intersectional framework into Marxism. Not only do Faes’s arguments read as homophobic and transphobic, but also misunderstand the necessary concessions to reformism that some groups are forced to take to improve their material conditions, because it lacks this intersectional analysis. In some cases, in order to prevent the literal deaths of actual human people, compromises on purity and principles must be made. One such example is that socialists sometimes have to make use of electoral politics in order to alleviate material suffering. Faes’s rejection of this necessity, which he calls “[t]he hard-Left’s calls to “queer” the existing Left to build a broad movement to pressure the Democratic Party” that “coalesce with the academic navel gazing inspired by Judith Butler…provide students with an anesthetic in that they avoid what was once historically possible and obscure their own lowered horizons,”[25] is a fundamental misunderstanding of the importance of reform within a broader network of socialist organizing. As Lenin explains in “Left-Wing” Communism, an Infantile Disorder:

[T]he Bolsheviks could not have preserved (let alone strengthened, developed and reinforced) the sound core of the revolutionary party of the proletariat in 1908-14 had they not strenuously fought for the viewpoint that it is obligatory to combine legal and illegal forms of struggle, that it is obligatory to participate even in the most reactionary parliament.[26]This quote, while often unfairly used as an argument for democratic socialism and fundamentally reformist ideologies, highlights the importance that reform has when coupled with other forms of non-electoral, revolutionary struggle. But, as Faes essentially condemns the whole of the LGBTQ+ movement in the 21st century to this reformist method (which, as he mostly ignores, can save lives), he is seemingly unaware of the LGBTQ+ organizations and activists engaged in revolutionary and radical struggles such as No Justice No Pride. Just as importantly, his attacks on the LGBTQ+ movement, equating it almost totally with the tactics of the Human Rights Campaign and other both homonormative and homonationalist organizations, should instead be leveled at the current socialist landscape for not appealing to the LGBTQ+ communities that he correctly points out are marginalized by these mainstream, neoliberal LGBTQ+ rights organizations and their appeals to the state. It is not the duty of the oppressed to just be magically educated, but rather it is the role of socialist organizations to agitate within oppressed communities, raise class consciousness, and illustrate why socialism should be the goal of these communities’ movements for liberation.

So, instead of accusing marginalized people who experience the debilitating effects of class oppression, racism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, etc. of division, reformism, and counterrevolutionary ideologies, the task should be to make sure that socialists and their organizations are adequately equipped to address the needs of particular communities. These communities are what constitute large portions of the working class, of revolutionary potential, and therefore their education and liberation must be central goals of socialist revolution. As Lenin said to Clara Zetkin:

Mobilization of the female masses, carried out with a clear understanding of principles and on a firm organizational basis, is a vital question for the Communist Parties and their victories. But let us not deceive ourselves. Our national sections still lack the proper understanding of this question. They adopt a passive, wait-and-see attitude when it comes to creating a mass movement of working women under communist leadership. They do not realize that developing and leading such a mass movement is an important part of all Party activity, as much as half of all the Party work. Their occasional recognition of the need and value of a purposeful, strong and numerous communist women’s movement is but platonic lip-service rather than a steady concern and task of the Party.

They regard agitation and propaganda among women and the task of rousing and revolutionizing them as of secondary importance, as the job of just the women-Communists. None but the latter are rebuked because the matter does not move ahead more quickly and strongly. This is wrong, fundamentally wrong! It is outright separatism.[27]

This statement still applies today, but not

just to the “woman question.” This strategy should encompass appeals on behalf

of socialism to communities of color, the LGBTQ+ community, immigrant

communities, people with disabilities, etc. If socialists cannot rouse these

communities to join behind the rallying cry of socialism, revolution, and the

eventual realization of a classless, communist society, then our goal is

already lost. The struggle for socialism is the struggle for liberation, not

just for those oppressed only by class exploitation, but also for those

oppressed by racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and all other symptoms of

the system of capitalism; it is our duty to ensure that ending these systems

intentionally and directing our efforts to alleviating their symptoms in the

process is a primary function of socialist organizations. | P

[1] D. M. Faes, “Transgender liberation? A movement whose time has passed,” Platypus Review 111 (November 2018). Accessed April 8, 2019. Available from: <https://platypus1917.org/2018/11/02/transgender-liberation-a-movement-whose-time-has-passed>

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] The Party for Socialism and Liberation, “The Marxist Understanding of the Roots of LGBTQ Oppression,” Liberation School (June 2015). Accessed April 8, 2019. Available from: <https://liberationschool.org/the-marxist-understanding-of-the-roots-of-lgbtq-oppression/>

[5] Harry Hay, Radically Gay: Gay Liberation in the Words of its Founder, ed. Will Roscoe (Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press, 1996), 37.

[6] Ibid., 43.

[7] Ibid., 42-43.

[8] Faes, “Transgender liberation?”

[9] Hay, Radically Gay, 37.

[10] Ibid., 43.

[11] Ibid., 176-7.

[12] Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective (Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books, 2017), 118.

[13] Ibid., 130.

[14] Ibid., 101.

[15] Silvia Federici and Nicole Cox, “Counter-Planning from the Kitchen,” in Silvia Federici, Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle (Oakland, California: PM Press, 2012), 28-29.

[16] Taylor, How We Get Free, 15.

[17] Ibid., 20.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, 1987. “The Three Sources and Three Component Parts of Marxism,” in Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, Introduction to Marx, Engels, Marxism (New York, New York: International Publishers, 1987), 42.

[20] Patricia Hill Collins and Sirma Bilge, “What is Intersectionality?,” in Patricia Hill Collins and Sirma Bilge, Intersectionality (Malden, Massachusetts: Polity Press, 2016), 25.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Taylor, How We Get Free, 69.

[24] Ibid., 22-23.

[25] Faes, “Transgender Liberation?”.

[26] Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, “Left-Wing” Communism, an Infantile Disorder (New York, New York: International Publishers, 1940), 21.

[27] Clara Zetkin, “My Recollections of Lenin,” in Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, The Emancipation of Women (New York, New York: International Publishers, 2011), 114.