#MeToo and the millennial sex panic

David Faes

Platypus Review 111 | November 2018

IT IS BY NOW WELL ESTABLISHED that millennials are not having sex. Indeed, recent studies have revealed that millennials derogate the emotions evoked in love and lust, which they refer to disparagingly as “catching feelings.”[1] The widespread paranoia surrounding consent presumably only deepens such sentiments. Because victimhood has become the visa stamp of critical insight and political solidarity, women are encouraged to conform their experiences to those of a victim while sympathetic men are encouraged to counter-identify with perpetrators through the burden of a collective guilt. This engenders resentment against those whose experiences do not comply.[2]

The two-fold desire to love and to be loved that surrounds the discovery of a beloved is disfigured in monochromatic emulsion. Millennials distort the feelings around this desire, which André Breton illustrated as “being both trapped and giving thanks,”[3] by cutting the discovery of desire into two irreconcilable fears: Was I abused and just didn't realize it? Did I abuse someone and not realize it? Now, when millennials are confronted with the emotions surrounding desire, for which they already did not have the disposition, they further placate their anxieties with the screen-image of abuse. The childish identification with either the prey or the predator prematurely resolves what is still at play emotionally and moreover condemns the mutually transactional character of romance. Rather than recognizing romance as a social relation of mutual self-possession and exchange, millennials neatly divide men and women and project this division upon all eternity as if men only want sex and women only want relationships.

The bourgeois social relation of romantic love that brought Eros, sex, and kinship into relation with one another—and which Kant famously characterized as the mutual self-possession of each other’s sexual capacities—remains an achievement of human freedom. In past civilizations, these relations—Eros, sex, and kinship—were broadly unrelated. For instance, in feudalism romance, marriage, and sex coexisted, however extraneously. In romantic courtly love, knights maintained a platonic, unconsummated, love for their beloved in court. This form of romance coexisted with traditional marriage, marital sex, and courtesan purveyed extra-marital sex, all of which were unromantic. By contrast, in bourgeois romance, the creation of the beloved as a counterpart in mutual self-possession and exchange has brought about the equality of the sexes and the possibility for new kinds of erotic, kinship, and sexual relations, such as modern romantic homosexuality. On this basis, the pursuit of love, Eros, sex, and kinship have since become part and parcel of the free pursuit of happiness. As Juliet Mitchell once incisively put it, just as capitalism has historically been a precondition of socialism, bourgeois marital relations have equally been a precondition of sexual emancipation.[4]

In capitalism, which Marx defined in terms of a crisis of bourgeois society and its social relations, these new opportunities for love, Eros, sex, and kinship--which emerged alongside bourgeois society--are likewise in crisis. While the opportunities for these kinds of freedom continue to be reproduced they are simultaneously undermined. The crisis of this bourgeois social relation of romantic love is complex because of its various constituent relations of erotic, sexual, and kinship ties. Consequently, the contemporary focus on “sexual liberation,” and more specifically “sexuality,” is too narrow to grasp all the moving parts. Not least of all because there is no alternative: love cannot be free in an unfree society. All attempts to imagine the free unfolding of our sexual, erotic, and kinship capacities are marked by the present society from which they spring. The impulses of libertinism and puritanism in response to the crisis of bourgeois romance are both stamped by their opposite.

A relatively clear example of this problematic is the utopian socialists' demands for the abolition and overcoming of romance, sex, and the family. Socialists since Babeuf and Fourier understood bourgeois romance and marriage to entail the private ownership of a spouse and called to replace marriage with a free and shared sexual community. This demand is itself a one-sided exaggeration of the bourgeois form of romance in the sense that in bourgeois romance people were, for the first time, able to give their love freely to others. The socialists’ demand was for a more complete realization of this latent possibility. Marx recognized that the socialists' demands for the abolition of the family would amount to a general prostitution of the community that was already taking place under capitalism. The industrial revolution already on its own had abolished the distinction between the sexes, and between the members of the family, since women and children were, out of necessity, compelled to work. Marx compared the demand to abolish the family to the demand to abolish private property, a demand which would amount to a community of laborers and commonly owned capital that would merely universalize the proletariat's present condition.[5] Thus, for Marx, the workers’ demand for socialism, including calls to abolish the distinctions between the sexes and the family, was itself a high expression of capitalism. While the historical dynamic of capitalism elaborated new social relations and forms that outstripped the traditional kinship, erotic, and sexual bonds, it did so on a basis that undermined these emerging relations and forms.

Certainly, since then there have been several reconfigurations of erotic, sexual, and familial ties within capitalism, for instance, the libertinism of the early-to-mid 20th century. The culture industry of that time encouraged sexual activity to the point that maintaining a “healthy sex life” became widely considered as a necessary aspect of personal hygiene. Adorno recognized that this social affirmation of sexuality undermined what sexuality had previously been, namely that which was socially unacceptable.[6] Consequently, the relationship between the emotional and erotic partial instincts that lead up to sexual consummation had become deprecated to prioritize the sterilization of the latter. Meanwhile, despite the widespread acceptance of dating, premarital sex, romantic films, sunbathing, and body culture, sexual taboos such as prostitution and homosexuality persisted in full force.

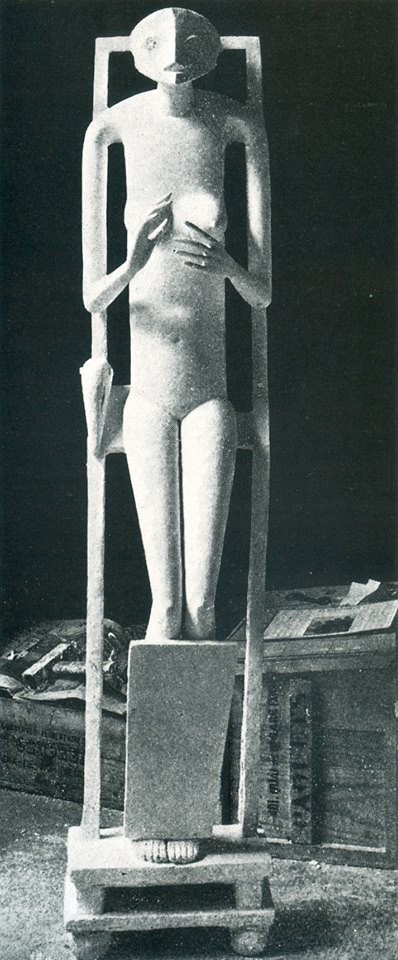

Alberto Giacometti Invisible Object (Hands Holding the Void) 1934, photograph by Dora Maar.

Conversely, while millennials exhibit preferences for sex without relationships, polyamory, queer transgenderism, and asexuality, they also exhibit a striking aversion to sex and the relations that surround it. It seems that millennials have inherited the impulses begotten by the New Left’s efforts for sexual emancipation, particularly the deployment of homosexuality as a means to free women of oppression by men. In a similar way, romantic relationships among millennials seem to be in the name of comradeship in the resistance. It is this barracks mentality, the grim and desperate homosexuality of the military unit, that motivates millennials to prioritize political opinion as the most important factor in choosing a sexual or romantic partner. That is to say, millennials, the majority of whom identify with Democrats, will only sleep with other Democrats. In such circumstances, the sex-starved youth have no choice but to comply. Moreover, the fear of diminishing opportunities in the labor market since the 2008 financial crisis and the concomitant panic around sexual consent have motivated most millennials to marry early, despite their worries that they are “settling.”

Certainly, millennials have created a subcultural alternative to married life in the form of online hook-up and dating apps. I say subculture because as of 2015 only 17% of millennials had ever used a dating app.[7] However, even this alternative resolution is marked by the barracks mentality and not only with respect to shared political opinions. The elaborate mechanisms around desire and consent—for instance, the assertion that verbal consent must be asked and given to even hold a beloved’s hand, or the convoluted identities based on sexual preferences—exhibit a puritanical anxiety around sex that can be administered through settings and preferences on dating and hook-up apps.

This resembles the offline sexual subcultures that emerged in the wake of the New Left in which members of the community are expected to excommunicate those who do not adhere to the expectations of the group. Certainly, this encourages blackmail and coercion in an effort to police oneself and others in the community – since, from their standpoint it would be better to err on the side of caution and act out against “the offender” than to substantiate the accusation in the first place. Such subcultural impulses are reminiscent of what Otto Fenichel had called the bi-phasic neurotic personality: behaving “alternately as though [one] were a naughty child and a strict punitive disciplinarian.”[8] The management of desire through these subcultural mechanisms attempts to assuage the anxieties and hostilities associated with dependency upon the beloved, the love for whom is felt as an intractable force, by promising to transform the narcissistic loss of the beloved—whether potential, actual or imagined--into the gain of removing the burden of autonomous responsibility and, not to mention, adding the additional masochistic gratification of self-deprecation. This reconciles millennials to their abdication of the free pursuit of happiness, exhibiting what Wilhelm Reich once called a “fear of freedom.”[9]

The existing, so-called “Left” is itself a subculture that is out of touch with whatever desire for or fear of freedom seems plausible among the masses today. That said, the Left has since 2006 put all their stock in the progressive millennials they helped to solidify as a constituent within the Democratic Party as part of their attempts at political education. The emergence of subcultural groups such as “Gays for Trump” and “Trannies for Trump” [sic] illustrates the bankruptcy of the contemporary Left. Trump appeals to people not as a subculture or particular interest, but rather in the interest of human individuals to freely pursue happiness—for example, he has said at his rallies that the LGBTQ community is an expression of American freedom. At the same time, the common leftist tropes that smack of paternalism about what kinds of sexual, kinship, and erotic activities are appropriate for women and LGBTQ people continue to persist in these Trumpist spheres.

The existing Left’s criticisms of the Democratic Party for its strategy regarding the Kavanaugh hearings amounts to a wish that the labor constituency within the Democratic Party could be more significant, just as the Left’s support amounts to a sop to the radical liberal progressive millennial Democrats. The Democrats have simply used existing sexual taboos as means to opportunistically win back suburban women from their support for Trump—a strategy which has only backfired. The Left in its opportunistic (“critical”) support for the Democrats reaffirms the existing sexual taboos rather than considering what it would mean to emancipate them. In this sense, the “Left” is simply a variant of the right. In such circumstances the task at hand would be to hold up the history of what the Left has been to reconsider what it can yet become, to hold ourselves steady as the sun sets on the millennial generation. | P

Alberto Giacometti Invisible Object (Hands Holding the Void) 1934, photograph by Dora Maar.

[1] Twenge, Jean M. Generation Me: Why Today's Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled—and More Miserable than Ever before. New York: Atria Paperback, 2014; Martinez, Gladys M., and Joyce C. Abma. ‘Sexual Activity, Contraceptive Use, and Childbearing of Teenagers Aged 15–19 in the United States’. NCHS Data Brief. National Center for Health Statistics, July 2015; Twenge, Jean M., Brittany Gentile, C. Nathan DeWall, Debbie Ma, Katharine Lacefield, and David R. Schurtz. ‘Birth Cohort Increases in Psychopathology among Young Americans, 1938–2007: A Cross-Temporal Meta-Analysis of the MMPI’. Clinical Psychology Review 30, no. 2 (1 March 2010): 145–54; Twenge, Jean M., Ryne A. Sherman, and Brooke E. Wells. ‘Sexual Inactivity During Young Adulthood Is More Common Among U.S. Millennials and IGen: Age, Period, and Cohort Effects on Having No Sexual Partners After Age 18’. Archives of Sexual Behavior 46, no. 2 (1 February 2017): 433–40.

[2] For instance, there has been resentment towards the Anti-#Metoo Manifesto, available in English translation at the following link: https://www.worldcrunch.com/opinion-analysis/full-translation-of-french-anti-metoo-manifesto-signed-by-catherine-deneuve

[3] Breton, André. Mad Love. Translated by Mary Ann. Caws. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988, p. 26.

[4] Juliet Mitchell, ‘Women: The Longest Revolution’, New Left Review, I, no. 40 (1966): 25.

[5] Marx, Karl. “Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844.” In K. Marx & F. Engels, Collected Works Vol. 3 (pp. 229–348). London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1959.

[6] Theodor W. Adorno, ‘Sexual Taboos and the Law Today’, in Critical Models: Interventions and Catchwords, trans. Henry W. Pickford, European Perspectives (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 71–88.

[7] ‘June 10-July 12, 2015 – Gaming, Jobs and Broadband’ (Pew Research Center, 9 April 2016), http://www.pewinternet.org/dataset/september-2014-march-2015-teens/.

[8] Fenichel, Otto. The Psychoanalytic Theory of Neurosis. London: Routledge, 1996, p. 291.

[9] Reich, Wilhelm. The Mass Psychology of Fascism. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1975.