Keeping the movement going: An interview with Gayle McLaughlin

William Lushbough

Platypus Review 103 | February 2018

Gayle McLaughlin served two four-year terms as the mayor of Richmond, California, first elected in 2006 and then reelected in 2010. She was first elected to city council in 2004 as a member of the Green Party and was again elected to the council in 2014 after finishing her second term as mayor. She is a co-founder of the Richmond Progressive Alliance, which enjoys a majority on the Richmond City Council. In 2017, Gayle announced her candidacy for Lieutenant Governor of California. The election will be held on November 6, 2018. What follows is an edited transcript of the interview conducted with McLaughlin by William Lushbough of the Platypus Affiliated Society on December 2, 2017, at her home in Richmond.

William Lushbough: In 2006 you were elected to the first of two four-year terms as the mayor of Richmond, California, the largest U.S. city to be led by a Green Party member. That made you one of the models for a successful local third-party campaign. What were some of the major challenges you faced running outside of the Democratic Party?

Gayle McLaughlin: The Democratic Party has never endorsed any of my campaigns. Now, local campaigns for City Council in California are non-partisan races, so I always make it clear that I am a member of the Green Party and of the Richmond Progressive Alliance (RPA), which is an organization that brings progressives together regardless of party affiliation or no-party affiliation. Richmond is a pretty Democratic city and I find that people resonate with my values; RPA values, it turns out, are the values of people all over Richmond and, I believe, beyond. So I made it clear that I was a member of the Green Party and stood for social justice, economic justice, ecological wisdom, grassroots democracy, etc. When you talk on a grassroots level to people, when you talk about the substance of your values, the party is easily set aside. Of course, the Greens that supported me were very pleased to embrace me, but it did not seem to interfere except for the endorsement process, which, I suppose, gets to the core of your question.

The Democratic Party would not and does not, to my knowledge, ever endorse a non-Democrat. The same goes for some of the building trade unions: in my first city council campaign, they said, “we never endorse Greens!” So there were obstacles in terms of getting endorsements. But, in terms of reaching the people, it just took a lot of grassroots work, going out to reach people. If anything it was Chevron’s interference that was the worst. They would send out misinformation and we had to really make it clear through an education campaign that we needed Chevron out of our city politics. “They have a big refinery in our city, they make billions of dollars, but democracy is for the people”—that was our message.

WL: Was Chevron part of the reason why you did not run as a Democrat?

GM: Chevron, just like all big corporations, will go with whoever will align with them. They can go with the Democrats, of course, or with Republicans, and if some independent lined up with their agenda, they would not have a problem with them either. For them, it is all their bottom line—who they can influence and manipulate.

WL: What originally made you decide to run as, specifically, a Green Party candidate for the mayor of Richmond? Why the Green Party?

GM: I joined the Green Party because their ten key values are values that I espouse. Also, they stated clearly that no corporate money should be in politics, which was very important to me. I have been an activist my whole adult life. Since I was a teenager, it has been clear to me that the big corporate-controlled parties were not representing the needs of people. They were not representing the needs of working families, the needs of oppressed populations. I started to align myself with other activists who were also looking for third-party alternatives. I never felt that someone being a registered Democrat constituted a barrier to dialogue.

So, when I ran for city council I was already a Green Party member. We had a local Richmond chapter. At first, we started out like a club of people who had Green values, but eventually we became an official group. I kept my registration as I ran for city council and mayor. The Green Party seemed to me at the time I registered to be gaining momentum. Ralph Nader had run on the Green Party ticket a couple of times. He had big rallies and that mass movement was something that I wanted to be a part of. It has always been linking up and helping to grow mass movements that has motivated my politics.

WL: So you just saw more promise engaging in that mass movement, rather than attempting to mount a change within the Democratic Party?

GM: Yeah I did, that is putting it well.

WL: Prior to your move to Richmond and your involvement in the RPA, you were involved in Chicago with the Committee In Solidarity with the People of El Salvador and also with the Chicago Rainbow Push Coalition. The question is: What informed your decision to shift from solidarity activism to municipal politics?

GM: I had been involved with more national and international issues—for instance, my anti-war work focused on stopping U.S. involvement in the war in El Salvador. When I moved to Richmond, as the super rallies for Ralph Nader started gaining momentum, it was clear to me that, as Bernie Sanders has recently emphasized, we need people to run at the local level, city council level, school-board level, and really to start shifting politics all over. I wanted to root myself in one place and get involved in local politics to be a part of the movement. So in Richmond we started having a dialogue among Richmond Greens and other progressives who eventually formed the RPA. We were doing some local politics already, but we were also doing anti-war work; we had participated in anti-war marches in San Francisco to oppose the occupation of Iraq. We had our hands in various levels of politics, local, state, and national, but our focus at a certain became the city’s many challenges: crime, poverty, and the health problems associated with the refinery. The city council was entirely in Chevron’s hands. We knew we had to make change. Of course, we always try to connect with the larger struggle. Richmond is not an island. We are a part of a country and a wider world, but we decided to root ourselves in the local struggle.

WL: You mentioned Chevron and your efforts to combat it. In 2013 you led the effort in the Richmond City Council to sue Chevron for the 2012 refinery fire. Going a little more broadly with that, how do you think the Left should approach the environmental crisis?

GM: What works first of all is community mobilizing. It is always the power of numbers that makes a difference. However, you also need people in decision-making positions. At all levels of government, you need progressives in office working side by side with the movement. In Richmond there was a time when Chevron representatives had a desk outside of the city manager's office. That is how dominant this big corporation was on our city hall. So, we had to break through, to make a crack in that system. We did that by mobilizing. We are grassroots organizers. We came together, put the party aside. By knocking on doors, making phone calls, going to community events, and having forums where we shared our views and the candidates were introduced. I was one candidate in 2004 and there was another one, Andrés Soto. We both had a chance to talk, but we also heard from community leaders and from the general public. So it was partially a matter of learning from the community what they were dealing with and partially educating the community about what we had done research on and what we had learned from dealing with the city council at that time, about how dominated our city was by Chevron. In the process, we had to break through a lot of misinformation: there was a lot of, “We need Chevron. Chevron pays the city so much in taxes.” So we had to say, “This is how much Chevron makes in profits operating in our city. This is how much asthma we have as a result. This is how over the years our community has gotten poorer.” Wealth inequality was something we were really clear on. So, that was how we broke through: by educating and learning from the community.

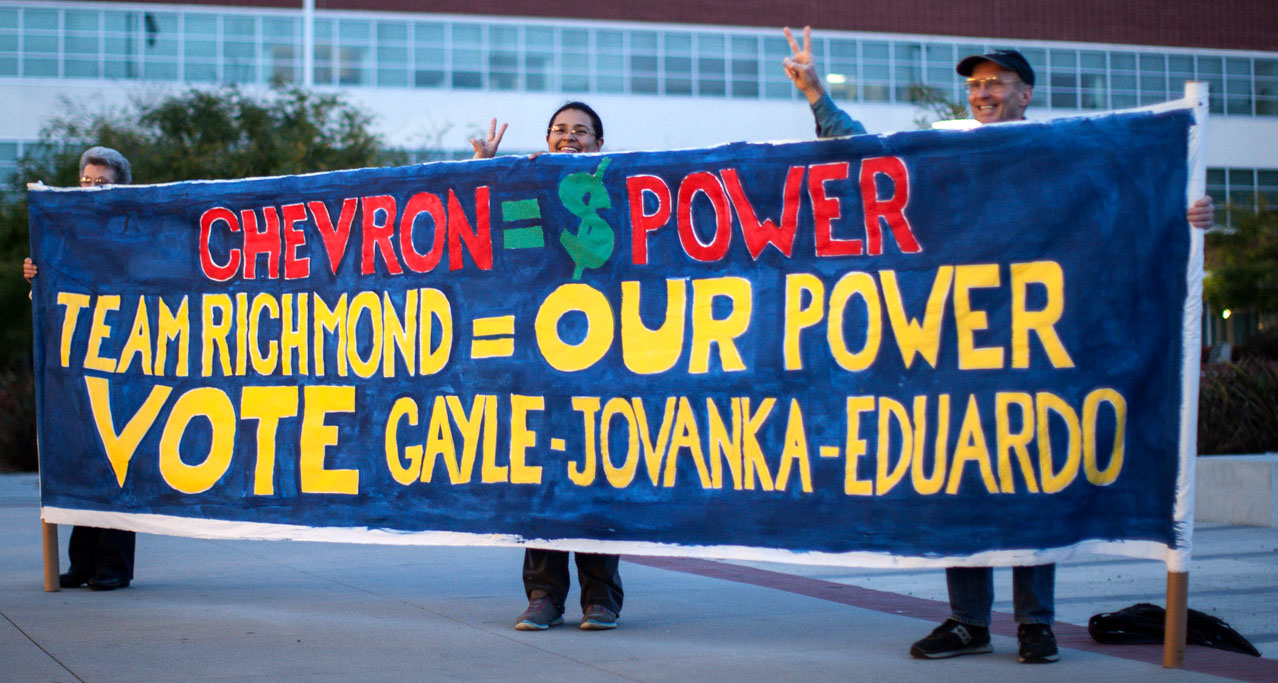

Richmond’s mayor Gayle McLaughlin and city council members Jovanka Beckles and Eduardo Martinez are all members of the anti-Chevron Richmond Progressive Alliance. (Photo by Martin Totland)

WL: What has not worked in your experience?

GM: Before the RPA came about there were lots of good activists—Fighting Against Chevron, the West Country Toxic Coalition, Communities for a Better Environment—all organizations we continue to work with. But they had no allies sitting on the city council, so they could only do so much. They would raise issues, saying, “We need Chevron to reduce its pollution.” And they did make some progress, but, by the time the RPA was forming, they were running up against obstacles. There were also challenges with non-profits because Chevron throws out little bits of money to city non-profits, by which they buy their silence. Chevron often uses the faces of the staff of non-profits in their newsletters. They buy up billboards and they put up the face of local non-profits saying, “We think Chevron is doing good work.” In reality, of course, the sums they throw to non-profits are nowhere near what they should be paying in fair taxation. We have made great progress in that, by the way. We got one hundred and fifty million in additional taxes from Chevron in the time I was mayor, but it is still not enough. But when you get more in taxation from big corporations, government—good government—can help the community. Good government can give grants to non-profits that are also doing good work. So we made the case: “Yeah, they give some money to non-profits. That is good. We are okay with that, but we are not okay with the fact that non-profits are thereby silenced. We want the truth to be told!” We would rather them pay more in taxes and go distribute the needed services from City Hall.

WL: Steve Early’s book Refinery Town sheds light on the economic transformation that gripped Richmond in the late 60s to early 70s. Richmond also seems to have been a hotbed of New Left radicalism in the late 60s. Early points out that the 1973 Shell Oil refinery strike was supported by the Bay Area Students for a Democratic Society and the Oil Chemical Atomic Workers led by labor environmentalist Tony Mazzocchi. So how did this earlier history inform the RPA later on?

GM: In the 60s there was a lot happening. I was not in the Bay Area at the time, but I know some of this history. In Richmond the Black Panthers had a chapter and ran a breakfast program that helped to dispense food to kids in local elementary schools. Of course, there was also union work around oil companies. But we in the RPA were not particularly reaching back to the 1960s. We all came from different struggles and many of us had an activist history in other countries. We all had a union support in our history and we all understood the importance and leadership role that unions have played and should continue to play. But at the time we were forming the Alliance, we mainly just saw the decline of the city. We knew there was good activism in the past, but we also knew there was growing poverty and crime. It is not just Richmond, of course. Urban environments everywhere in this period saw a decline of neighborhoods, especially people-of-color neighborhoods, and a rise in crime. We wanted to really turn that downward spiral around, and to start the trajectory spiraling up in terms of communities’ health, wellbeing, and happiness. These big corporations are the opposition. Chevron was our big “one percenter” in Richmond. So, there were grassroots organizations even as Richmond started going downhill. We stood on the shoulders of the many who went before, but we did form this independent organization and did something that no other organization in Richmond had done: run people for office without corporate money who would stand side by side with, and be organizers themselves within, the movement. That was unique: To have elected officials, corporate-free elected officials, be organizers as well. It is not like you get elected and join some elite class of elected officials. No, you still have to build and organize with the community, the movement in general.

WL: To piggyback on that point on the RPA being both activists and officeholders: Since the 2016 election the RPA has held a supermajority on the city council. What have been the biggest hurdles to implementing your program within a municipal government?

GM: There have been a lot of challenges. Chevron has opposed us at every juncture. Our elections are flooded with Chevron money. For instance, in 2014 they spent three and a half million dollars to defeat me and two other progressives running for city council. We all won and all the Chevron-funded candidates lost. During election season their money was a big challenge that we have had to overcome. We had to reach out to people and tell them to read the small print on the mailers: “funded by Chevron.” Also, once I got into office, it was very hard. I would be sitting in these closed sessions with people I did not agree with. In open sessions at least the community would be there so I felt less isolated. People would come to city council meetings, speak at the public podium, and give the progressive viewpoint that I gave from the dais. But it was still hard. We lost many votes, but we also won many votes by mobilizing the community. For example, there was a resolution that I brought when I was in first year as a city council member to have the right state department oversight on some toxic land in Richmond. We needed a comprehensive cleanup of this Superfund site with its nasty brew of toxins left over by then-departed heavy industries. I brought the resolution forward; though I knew the other city council members were not going to listen to me. They wanted to build on that land even though it was not properly cleaned up. So, we organized the community. There were 35 speakers who came and held up signs “protect our health,” “no development until it is comprehensively cleaned up,” and others. It put pressure on the other council members and they ended up voting for my resolution. That is how we made progress when we were in a minority. In later years there would be one more RPA person joining me, then two more. But we were always in a minority, so always aware that the voice of the community had to enter that council chamber directly as well as through us.

Now we have a supermajority, but we still have movement-building going on. And we want people in the council chambers because that is what democracy is all about. You cannot just have elected officials, even if they are wonderful and corporate-free, making decisions in isolation from the community. Every individual brings their own personal insight and experience and that impacts the overall dialogue and the ultimate decision. We still have a very active community and, of course, we have the votes on the city council, but we still put pressure on the other two non-RPA councilors to wake up and see that we have to go in the progressive direction, if we are really going to move our city further. The city has already transformed quite amazingly from what it used to be, but we have to keep up the pressure and keep the transformation going.

WL: On keeping that transformation going, I am wondering if there have been political limits to that, and if those limits prompted the lieutenant governor campaign?

GM: What prompted me to run this statewide race is that, after November 2016, when we got two more RPA members elected to the council—which gave us five-out-of-seven corporate-free members on the council—we found that people all over the Bay Area, all over California, and even throughout the nation were asking us, “How did you do it? How did you transform the politics? How did you make the phenomenal changes you made in Richmond?” We reduced homicide by 75%. We raised the minimum wage to $15 per hour. We passed the first new rent control law in California in 30 years. We joined a community choice energy program where 85% of our residents get their electricity from cleaner, greener, and cheaper sources of energy. “So, how did you do all of this?” people asked. I started giving presentations sharing the RPA model. Of course, every community has their own issues and their own style of organizing, but we feel we have a lot of tools that people can use. At a certain point it became clear to some of us in the RPA that running a statewide race would give a larger stage to the message of building progressive alliances. So I decided to run for lieutenant governor as an organizing project to encourage progressive alliances to be built all over California. Already something like seven or eight of them have emerged. I am running to win and, hopefully, when I win, I will keep the organizing going and network the alliances and all the Our Revolution (OR) groups. I have already received 26 local California OR group endorsements. The idea is to build a statewide movement, network these local groups together, and we will have that power to address our statewide issues. So, that is what prompted me to run for lieutenant governor.

The challenges and limitations that remain on the city council in Richmond is that Mayor Tom Butt has grown further away from the RPA and become very market-oriented. For instance, he is very much opposed to rent control. We do not think he has much of a following anymore. Previously, he was somewhat allied to us and that is how he got to be mayor.

WL: You have said before at the Howard Zinn Book Fair that you would consider this campaign a success as long as it established more progressive alliances throughout California, teaching different cities the tools that you have used to do what you have done and also to bolster the OR movement. Who do you see as potentially building these political efforts from the ground up?

GM: There are so many great progressives leaders up and down California. It has been just really inspiring to be traveling and meeting so many progressive groups coming together in coalition, in San Diego, Los Angeles, South Bay, San Jose, the North Coast, and San Francisco. What Bernie did in 2016 was really to move the progressive movement forward. We often say in the RPA “he moved us forward 30 years.” We have been working really hard in various areas, but now we had this person connecting us all, making the case for our progressive values nationwide. People got a big boost with Bernie. My role as a candidate, the role of my campaign, has been to keep that movement going and spread the word about the RPA. Bernie said “we have to have progressive elected officials at all levels of government” and people heard that. More and more people are stepping up to run as corporate-free candidates on the local level, for state assembly, etc. Now the term we coined, “corporate-free,” has become very common.

WL: I noticed that you reached out to the East Bay Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) for an endorsement.[i] I am wondering why did you want their endorsement for your lieutenant governor campaign? What kind alliance do you envision with that organization which seems to be different demographically than the RPA, where it is more so younger activists in their early 30s while the RPA is more seasoned older activists?

GM: The RPA steering committee is very young. We have a 28-person steering committee: It has a majority of people of color, a majority of women, and a majority of people under forty. The progressive mindset of diversity was always a very much a part of our agenda. But still we can use more millennials.

DSA is very youth-driven. They have grown especially since the Bernie campaign. Bernie made the term “socialist” much more common and much more acceptable throughout our nation. I have always had the socialist mindset and I think the whole anti-corporate struggle is a struggle against capitalism and the harm that it causes. So reaching out to DSA was important. They are a part, a very strong part, of our movement for change. I was very excited to get the endorsement of East Bay DSA, San Francisco DSA, and Peninsula DSA. I hope to receive the Los Angles DSA endorsement as well.

WL: Regarding the issues that you are fighting for or the problems you are fighting against, what do you see as the root? Do you see it as capitalism or greed? What is it for you?

GM: When it comes to small businesses, small-time capitalism, many are just barely making it. As a candidate I take no corporate money or even small business money; that is where I draw the line. I only receive small donations from individuals. But we do see the small business community as a good element for our communities and the same is true even of other, bigger businesses that are being responsible. But capitalism has allowed mega-corporations to create enormous wealth and income inequality. If we can work together we can regulate corporations and ultimately build the kind of socialist society that we all, including future generations, can thrive in.

WL: Going back to the Our Revolution (OR) political action organization that grew out of the Bernie Sanders campaign, based on your history on running outside the Democratic Party, I am wondering if you worry about this organization moving voters back into that party?

GM: The national OR, based in Washington D.C., is one thing, and then there are all the local chapters. We have been in touch with the national group as well as all the local groups. I find that the national group is being clear: We have heard it from Nina Turner that their endorsement process has been and will be based not on party but on progressive values, i.e. on whether or not the local OR's support the candidates. So the national OR has yet to endorse for the lieutenant governor race, but I have more local OR endorsements than any candidate in the nation with 26 California OR endorsements. So I hope that is meaningful to the national OR and they will endorse me.

As for leading people back into the Democratic Party, the way I approach it is that a lot of the OR folks are in the Democratic Party but they fight the good fight within it. I consider myself an independent Berniecrat, but there are, of course, the Democratic Party Berniecrats and I support them because they are fighting a good fight. They really want to take control of the party away from the corporate Democrats. So I say, “Go for it! If you win (and I hope you do), it really will not be the same party anymore. It will be something totally new, because for decades the Democratic Party have been corporate controlled.” So I am staying on the outside. I am connecting Green Party, Peace and Freedom Party, those with no party affiliation, and progressive Democrats. But I understand people feel a strong momentum and want to do all they can to change the Democratic Party and that is a good thing too.

WL: Many political movements on the Right make appeals that are similar to progressive and social democratic movements. For instance, President Donald Trump ran his campaign promising to create more jobs, to make healthcare more affordable, and to end political corruption. In what ways do groups like OR and RPA distinguish themselves to the voter from right-wing movements that make similar pleas?

GM: When we talk about an independent political movement we have to say an independent progressive political movement. What Donald Trump and the right-wingers are promoting is that they are going to change politics, but we know otherwise. We have to bring out the hypocrisy and the lack of moral foundation of Donald Trump and his people, the bad policies that they are putting out, and how those policies will impact your average working middle class person, the unemployed, struggling families, and the homeless. The people that have followed Donald Trump have been really bamboozled. The average Trump supporter does not understand where he is leading us.

We should not be afraid of engaging with Trump’s supporters and sharing the truth about where we are at as a society and the catastrophic freefall that this president is bringing the whole world into. These are dire times. We should reach out to average people, regardless of where they have been or how they have been manipulated in the past: That will be part of the change. We have to break through the false notions some people have about how things are going to change. He has to say to them, “Hey, it is not an easy struggle we are in, but each of us has a role and together there is a joy in this struggle.” Because solidarity with one another brings us closer as human beings and gives us joy in making change together. That us how it will be done, not by looking towards a false leader like Donald Trump.|P

[i]“As a nascent organization, we should be flattered that Gayle McLaughlin and Jovanka Beckles would reach out to us for an endorsement. Such a request speaks volumes about the work we've done since November or longer in the case of our seasoned members.” Herrera Cuevas, Antonio. Orr, William. 'Until Our Members Have Agency, EBDSA Should Not Endorse'. Available online at: http://www.eastbaydsa.org/resources-endorsements-until-members-have-agency-ebdsa-should-not-endorse