Horkheimer on Lenin’s “Empiriocriticism” – Max Horkheimer’s 1928–29 reaction to Lenin’s epistemological polemic Materialism and Empiriocriticism

Michael Jekel

Platypus Review 98 | July-August 2017

This is the first translation from the German-language Platypus Review to appear in the English edition. The original can be found at <platypus1917.org/2016/10/19/horkheimer-uber-lenins-empiriokritizismus/>

Material Basis

AMONGST HIS MANUSCRIPTS Max Horkheimer left behind an essay, written in 1928 but unpublished during his lifetime, whose subject is Lenin's important work Materialism and Empiriocriticism, which had appeared in German translation the year before. The publication of Horkheimer’s response to Lenin was eventually undertaken by Horkheimer’s pupil and successor, Alfred Schmidt in 1985.[1] Schmidt’s editorial remarks reveal that Horkheimer's views on Lenin's epistemological polemic crystallized sometime in the Winter semester of 1928, when the already habilitated lecturer was teaching at the University of Frankfurt. The manuscript, which originally lacked a title, is contained in a notebook. This original version was then used as the basis for a 17-page typewritten copy (with Horkheimer’s own handwritten corrections). In addition, a separate 11-page typed manuscript, which seems to have served as the outline for a lecture given in the summer semester of 1928, has also been preserved.[2]

Horkheimer’s critical confrontation with Lenin's epistemological polemic takes place at a time when Horkheimer was just beginning to gain a firm foothold in academia. Born in 1895, he received his doctorate in 1922 with a work on Kant's antinomy of the teleological power of judgment. In 1925, he was habilitated with a work on Kant’s Critique of Judgment as the mediation between theoretical and practical philosophy. Both of these theses were supervised by the neo-Kantian philosopher Hans Cornelius, who held a professorship in Philosophy at the recently established University of Frankfurt. In Materialism and Empiriocriticism Lenin had directed a sharply worded polemic against Cornelius, dubbing him a “police sergeant in a professorial chair.”[3] As Horkheimer was an active research associate with Cornelius when he composed his thoughts on Lenin’s text, it would seem that in Frankfurt, there was an old bill with Lenin still open.

Horkheimer's Lenin manuscript of 1928–29 can be divided into three sections: In the first, Horkheimer lays out Materialism and Empiriocriticism’s argument against the Austrian physicist Ernst Mach. Following this reconstruction Horkheimer sets out a sharp critique of Lenin’s anti-Machean position. Finally, in the last and shortest section of the manuscript, Horkheimer makes clear that, despite the serious deficiencies of Lenin’s argumentation, he nonetheless takes Lenin’s philosophical concern seriously and that Materialism and Empiricocriticism is neither obsolete nor irrelevant.

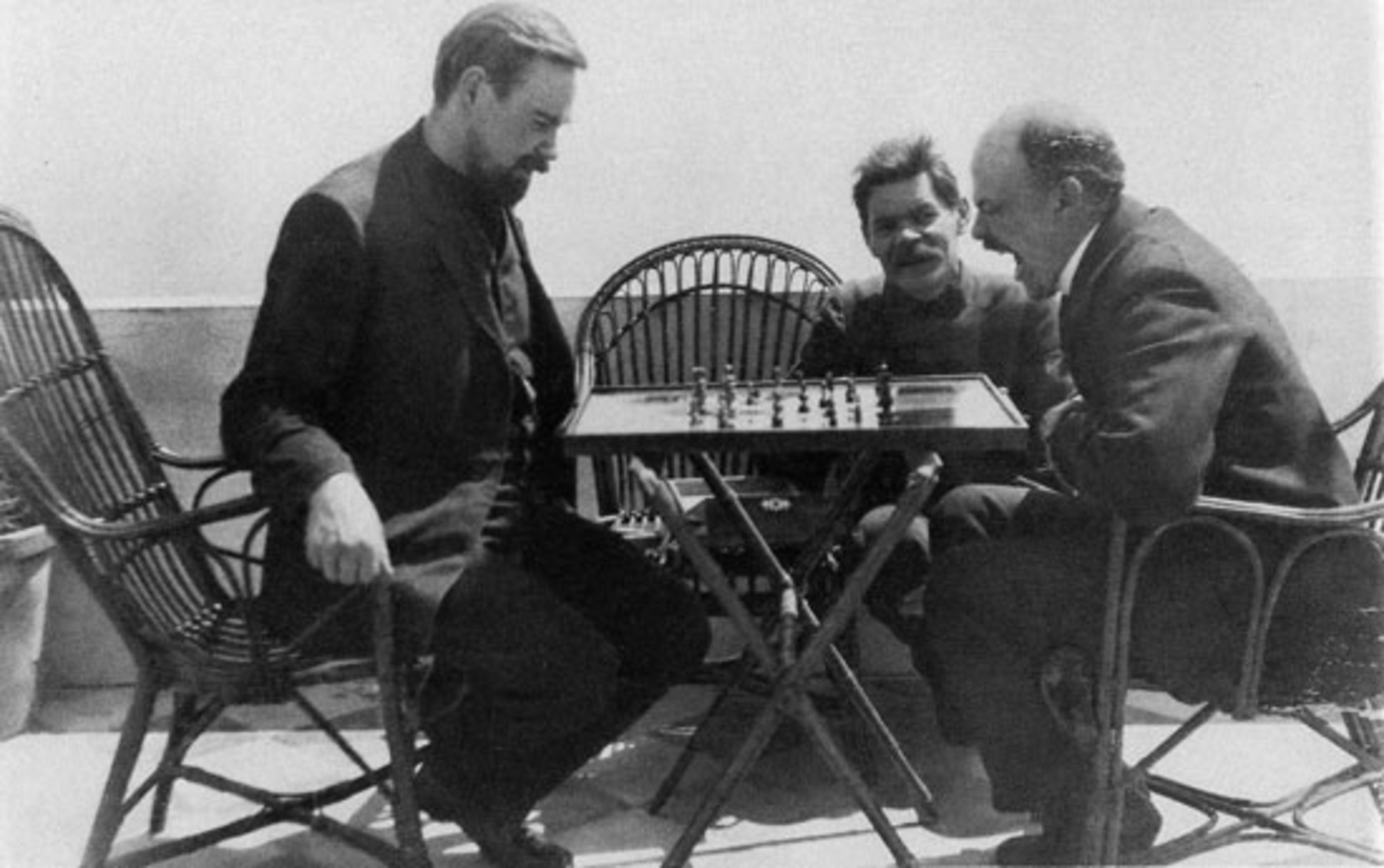

Lenin playing chess with Alexander Bogdanov, one of those who brought philosophical disputes into political debates within Russian Social Democracy thereby prompting Lenin to write Materialism and Empirio-Criticism. The photo was taken at Maxim Gorky's house in 1908.

Mirroring the Mirrored

The epistemological linchpin of Materialism and Empiriocriticism is found in the following central passage (also taken up by Horkheimer) from Engels' Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy: “Those who asserted the primacy of spirit to nature and, therefore, in the last instance, assumed world creation in some form or other... comprised the camp of idealism. The others, who regarded nature as primary, belong to the various schools of materialism.”[4] Horkheimer comments, “Nature, matter, objectivity are designations for the reality investigated by the positive sciences, the knowledge of which is provisional in the most advanced theories.”[5]

In the 1900s, the conception of matter underwent a fundamental change. The atom, as was said at the time, began to dissolve; waves and vibrations taking its place. Matter dematerialized. In his PhD thesis, published in 1962, Alfred Schmidt explains that “at the turn of the century… the ‘disappearance of matter’ and the future impossibility of a philosophical materialism [were] being mooted in connection with epoch-making discoveries in physics.”[6] It was against this mélange of ideologies of science that Lenin reacted, vigorously opposing any theoretical reformulation of Marxism, any renunciation of its materialistic basis.

In Materialism and Empiriocriticism, Lenin develops a perhaps unfamiliar, rather minimalist definition of matter with which he—in response to the apparent disappearance of matter in the new physics of the time—attempts to specify or open up the concept with a view to the more unconventional forms in which matters appears as well. The concept of matter, as Lenin philosophically conceives it, includes not only matter’s seemingly static forms of being, but also matter in its less tangible form of waves, oscillations, and energy. According to Lenin (in a passage both Horkheimer and Schmidt point to), “the sole 'property' of matter with whose recognition philosophical materialism is bound up,” is the “property of being an objective reality, of existing outside our mind.”[7]

The philosophical concept of matter is, therefore, not rigidly bound to the development of natural science. As Horkheimer explains, “The absolutization of individual phases of the scientific process of knowledge leads to static metaphysics, to the denial of the existence of truth, to relativistic agnosticism.”[8] According to the materialist view, every true theory, in spite of all errors and relative imperfections, has in a dialectical way an objective (if incomplete) share in the trans-subjective absolute truth “insofar as it is a necessary moment of progress in knowledge, for, through it, we produce not only appearance, but we get closer to an exact image of reality.”[9] Horkheimer later elaborates that every theory “is subject to correction through practice. This dialectical view distinguishes Lenin from those materialists who regard definite views on atomic structure, etc. as final.”[10] According to Horkheimer, Lenin sees scientific research “as an approximation to the adequate knowledge of the intersubjective reality transcending the consciousness of human beings… and as the only way to the realization of the only reality.”[11] Consequently, Ernst Mach according to Lenin is “a pure idealist, his philosophy essentially a mere reprint of Berkeley's. For Mach, our sensations are at the same time the elements of the material world. The natural things are connections of sensations, [even] the self itself is a relatively stable complex of memories, moods, feelings.”[12]

The doctrine of the Austrian physicist, on whom the Empiriocriticists in Russian revolutionary social-democracy (who mistook themselves for Marxists) were depending in their philosophical opposition against Lenin, Horkheimer further characterizes as follows: “For Mach, it is not the case that an identical reality is reflected in the consciousness of [different] people, that the different perceptions of several persons each correspond to a constant objective thing as the original; this view means for Mach as well as for his predecessor Berkeley a completely useless doubling of the world.”[13] Here perhaps it might be clear to what extent Ernst Mach can be regarded as a pioneer of positivistic, antirealist, and reality-constructivist theories of knowledge, even if these do not appear under the label of “Empiriocriticism” these days any longer. As Horkheimer characterizes such positions: “The ‘opposition of appearance and reality, of appearance and thing’ corresponds to inaccurate vulgar thought. What we know are not consciousness-transcending things, but, in the end, only our sensations and their functional relations… All our knowledge is related to our sensations. They are the ultimate facts themselves…”[14]

Horkheimer’s arbitration of the philosophical contest between Mach and Lenin sees Lenin triumphant, judging the case of Mach's theory of knowledge thus:

Engels' definition of idealism undoubtedly applies to this philosophy. Sensations and not nature are regarded as the primary thing, the world of material objects [is regarded] as a product of conceptual orders of the data at hand… Mach's thought corresponds precisely to the idealistic thesis of the original identity of thought and being, which Engels combats. Empiriocriticism therefore runs counter to the philosophical views of Marx and Engels.[15]

According to Lenin, Mach involves himself in insoluble contradictions. As soon as he pursues natural research as a physicist, he stands “like most naturalists, ‘instinctively on the standpoint of the materialist theory of knowledge,’” whereas “his philosophical principles” are to the contrary “the purest idealism.”[16] As an especially decisive argument against Mach, Horkheimer highlights the incompatibility of his epistemological doctrine with the objective reality of biological evolution and human history. With regard to this weakness in Mach's theory of knowledge, Horkheimer asks: “How can Mach admit the reality of human and natural history, when, according to him, ‘the entire course of time is bound only to the conditions of sensibility?’”[17] In this respect, Horkheimer arrives at a judgment straightforwardly adverse to Mach: “Lenin's conviction that the reality of history is not compatible with this doctrine points out, in fact, the weakest part of [Mach’s] philosophy.”[18]

Criticism of Criticism

The fact that Horkheimer agrees with Lenin on the central points of his polemic against Mach does not mean that he agrees with Lenin in every respect. Rather, Horkheimer proceeds to follow up his faithful rendering of Lenin’s criticism against Mach with a criticism against Lenin’s own epistemological premises in a choice of language no less harsh. Thus, Horkheimer holds Lenin’s conception of materialism to account—as far as its lack of epistemological sophistication is concerned—as naive and undialectical, and therefore hopelessly lagging behind what had already been achieved by Marx and Engels, and, indeed, by Feuerbach preceding them. Of course, Horkheimer is aware of the context within which Lenin's philosophical polemic fulfilled a tangible purpose in the inner-party political struggle over the orientation of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party:

The book is an application of selected formulations of Engels, tailored to the then prevailing party situation in Russia. It is the accidental work of a leader who vigorously calls the materialist word to mind and outlaws deviation. Again and again Lenin maintains the same propositions against ever new authors, without their supplying any new substantive basis: In the world there is nothing else but moving matter, and this matter moves in space and time. It is independent of our sensations, which themselves represent only the highest product of definitely organized matter. Our conceptions of reality are relative, but, ‘in their development, they are progressing in the direction of absolute truth, gradually approximating it.’[19]

Lenin had succeeded in convincing Horkheimer that Mach's theory of knowledge was indeed contrary to Marx and Engels's worldview, something unclear to the Russian Machists who considered themselves good Marxists. Still, Lenin fails to prove either that the materialistic view of the world is indeed correct, or that the idealist or Machean view is itself misguided. At least he does not establish this to the satisfaction of the Frankfurt critical theorist, schooled as he is in the theoretical lore of both Kant and Cornelius.

Horkheimer criticizes Lenin for making the same mistake as Mach and his followers, namely, that they juxtapose their own inadequately justified abstract dogmatic views to the ungrounded dogmatic, abstract views of their opponent, instead of resolutely taking up an elevated position, overlooking any such competing dogmatic views from elevated heights. Horkheimer: “The mere opposition of one's own abstract beliefs to individual views of Mach is little in keeping with the Hegelian sentence otherwise theorized by Plekhanov and Lenin: ‘there is no abstract truth, the truth is always concrete.’”[20] Lenin, however, finds himself in a situation in which he is directly taking part in a contemporary philosophical scuffle in which he is personally striving to preserve himself and to prevail with his view, whereas Horkheimer looks back from a much less dangerous vantage point of historical distance at blows exchanged a long time ago.

If we are to try to defend Lenin against Horkheimer's accusation of dialectical shortcoming, then a comparison of Materialism and Empiriocriticism with Engels' Anti-Dühring might be further illuminating. When we compare the task that Lenin faces with that of Engels against the vulgar-Marxist demagogue Dühring, it is evident that Engels was chiefly concerned with struggling against an opponent who, though considering himself a materialist, nonetheless entirely distorts materialism due to his ignorance of dialectics. For this reason, Engels “laid the emphasis […] rather on dialectical materialism than on dialectical materialism.” He “insisted rather on historical materialism than on historical materialism.”[21] For Engels, then, this was all about the defense of dialectical materialism against a vulgar-materialist opponent. Lenin, by contrast, faces a completely different challenge: Materialism is declared superfluous by the philosophical opponent; Marxism is therefore to be purified of it. Dialectics is therefore not an ideological battleground in this dispute, which is why it remains in the background unscathed. The East German Marxist literary theorist Werner Krauss explains:

The danger of idealistic temptations was greater in Lenin's time than in the time of Marx and Engels. The founders of socialism had, above all, to enforce their dialectical method against the prevailing vulgar materialism. During Lenin's time, the reactionary bourgeoisie had broadly re-established the connection with pre-Hegelian idealism. This led to the need expressed by Lenin to emphasize dialectical materialism more than dialectical materialism.[22]

Critical Aufhebung

Although Horkheimer, with his objections in the critical middle section, cannot find anything good to say about the argumentation of Materialism and Empiriocriticism, at the conclusion of his manuscript he arrives by a surprising twist at an overall assessment that is unexpectedly Lenin-friendly, at least as regards the function and motivation of Lenin's epistemological work. After Horkheimer has delivered many of the objections to be expected from somebody educated within the neo-Kantian community of professional philosophers, he performs a radical turn, transgressing the limits of academic, purely ‘inner-philosophical’ philosophizing, thereby opening up a perspective on extra-philosophical contexts and how they determine the reciprocal relationship between social reality and philosophical practice. While he continues to defend Mach, he does so chiefly in the view that during the interwar period the latter’s doctrines were already largely “exiled from the universities,” a phenomenon largely connected to the imminent disappearance of the “positivistic remnants in the petite bourgeoisie” associated with Mach. Therefore, Horkheimer concludes, the “most important and current sense of the book… is not at all the substantive arguments against Mach”[23] (for “Machism” can already be regarded as defeated). Instead, Horkheimer takes up Lenin’s combative impulse in order to wield it, not against Mach himself, but now in a sense towards a materialist critique of the idealistic reversion to philosophical mystification and metaphysics that was coming to increasingly dominate the philosophical institutions of his time. “The philosophy of the present phase of imperialism” is criticized by Horkheimer for its “pantheistic ontology” and “pseudo-practicality” quite contrary to Mach's scientism and nominalism.[24]

Horkheimer’s intellectual engagement with Lenin probably serves well to illuminate the path of Horkheimer’s gradual development from the Cornelius pupil to the critical theorist. Through his study of Lenin, the still relatively young junior lecturer felt himself strengthened in his impulse to no longer pursue philosophy in a pretended sphere of “social relationlessness” and professional isolation, but instead to understand philosophy “in the context of the social whole, in which it develops, out of which its contents originate, and in which it works.”[25] By introducing this critical change in perspective, Horkheimer sweeps aside the weight of his previous philosophical objections to Materialism and Empiriocriticism with, so to speak, a single wave of his hand. Certainly one can try to challenge the work of the philosophical outsider Lenin on various technical and professional grounds. But what this misses, however, is Materialism and Empiriocriticism’s capacity, despite the specificity of the context in which it was written, to provoke the critical reader to lift the philosophical blinkers from his eyes and to resist letting himself be so easily misled in the field of the philosophy of science.

First of all, Horkheimer tries to make good on the issue that he feels Lenin fails to carry through to its final consequences: Instead of countering the anti-realist theory of Ernst Mach directly, he makes an attempt to explain in an indirect way its ideological function under the social conditions of its time. As Alfred Schmidt points out, what Horkheimer finds missing “in the Russian revolutionary’s book [is] the application of historical materialism to the critical analysis of the Machian doctrines.” For this reason Horkheimer takes recourse at the end of his lecture (in this way grounding his critique of Lenin directly on Marx and Engels) “to the famous sentences of the German Ideology,”[26] according to which “the production of ideas, of conceptions, of consciousness, is… directly interwoven with the material activity and the material intercourse of men” and that even “the phantoms formed in the human brain are… necessarily, sublimates of their material life-process, which is empirically verifiable and bound to material premises.”[27]

Being determines consciousness: This is certainly also true for the epistemological phantoms in the field of Empiriocriticism. The task outlined by Marx and Engels, applied to the challenge of the teachings of Mach, Horkheimer formulates as follows:

It would have been necessary… to show how the social reality of Austria around the turn of the century could lead to the petty bourgeois philosophy of Mach…, what kind of social situation is expressed in such a philosophy… In this way, Lenin could have perhaps found out that this [idealist] epistemological theory, which relocates the criterion for all knowledge in the sensations of the individual subject and identifies the world with the consciousness of the citizen, necessarily corresponds to a more self-assured petite bourgeoisie—one that believes in greater chances of advancement in his society and has a more unbroken faith in the possibility of the individual’s progressing out of his class—than can be the case in later times of the stable domination of trusts.[28]

Under the conditions of “the stable domination of trusts” in the period around 1928, with the imminent National Socialist catastrophe beginning to loom in the late phase of the Weimar Republic, Machism hardly presented a serious challenge and had long since forfeited its intellectual appeal to the bourgeois camp. For, the “times when every individual subject could appear as a builder and critic of his own world are over. Kant and Mach are fought philosophically with the same categories as Marxism and appear as [stuck in the] nineteenth century.”[29] Further, “today’s social practice shows other characteristics than the capitalism of 1908, and with it the dominant metaphysical ideas have become different as well. Lenin had himself predicted [in Materialism and Empiriocriticism] that the ‘infatuation for empirio-criticism and “physical” idealism’” would rapidly blow over.[30] At the same time, however, Horkheimer maintains that, despite all the philosophical deficiencies and complaints, we are dealing here with a book that is still significant for his own time. For what still remains problematic in a way that has not changed is “the general function of ideology as such in class society. So far as the book is concerned with this function in its generality, it is by no means obsolete, despite any technical ignorance and the way it comes through as opportunistic in its style and layout.”[31]

Schmidt ultimately arrives at the conclusion that Horkheimer's engagement with Materialism and Empiriocriticism represents “a significant stage of his philosophical self-understanding.”[32] And, indeed, this seems to be evident from the final sentence of Horkheimer's manuscript on Lenin: “As long as the conversation remains ‘philosophical,’ the present metaphysics is as little comprehended as any earlier one. Critical seriousness begins with the barbaric transgression into economics and politics, and Lenin's book points in this direction. He took philosophy seriously.”[33] This conclusion might perhaps be interpreted as an indication that Horkheimer's path of emancipation—from various idealistic, positivist, and neo-Kantian predecessors, through his Machean dissertation advisor Cornelius (himself polemically combatted and berated by Lenin)—may be regarded as definitive. As an indication of Lenin's continued influence on Horkheimer, Schmidt also mentions a passage from the 1933 essay “Materialism and Metaphysics”: “The real meaning [of Materialism] is the exact opposite of any attempt to absolutize particular scientific doctrines… Materialism is not tied down to a set conception of matter; no authority has a say on what matter is except natural science as it moves forward.”[34]

Those who are somewhat familiar with Materialism and Empiriocriticism may perhaps see this idea to have its roots in Lenin's minimalistic philosophical definition of the concept of matter. Lenin’s idea seems to have had a lasting effect, since Horkheimer’s engagement with Lenin’s epistemological theory also continues in his later works, even if in an implicit manner, and in a way not immediately recognizable at first glance. As Schmidt says, it persists in a way “which is to be deciphered by the connoisseur.”[35] Thus, whoever wants to really understand Horkheimer and Critical Theory would do well to first take a close look at Lenin's book Materialism and Empiriocriticism.|P

Translated by Clint Montgomery

[1] Alfred Schmidt, “Editorische Vorbemerkung” [“Editorial Introduction”] to Max Horkheimer, “Über Lenins Materialismus und Empiriokritizismus,” in Max Horkheimer: Gesammelte Schriften, Vol. 11 (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Verlag, 1987), 171.

[2] Max Horkheimer, “Lenin, Empiriokritizismus,” typescript available online at <http://sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/horkheimer/content/pageview/6553849>.

[3] V. I. Lenin, Materialism and Empirio-Criticism: Critical Comments on a Reactionary Philosophy [1908], in Collected Works, Vol. 14 (Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1962), 219, also available at <https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1908/mec/four4.htm>.

[4] Friedrich Engels, Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy [1886], cited in Horkheimer, “Über Lenins Materialismus und Empiriokritizismus,” 176.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Alfred Schmidt, The Concept of Nature in Marx, trans. Ben Fowkes (London: Verso, 2014), 63–4.

[7] Lenin, Materialism and Empirio-Criticism, cited in Horkheimer, “Über Lenins Materialismus und Empiriokritizismus,” 176.

[8] Horkheimer, “Über Lenins Materialismus und Empiriokritizismus,” 176.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid., 176–7.

[11] Ibid., 177.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid., 177–8.

[15] Ibid. 178.

[16] Ibid., 179.

[17] Ibid., 180.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid., 183.

[20] Ibid., 184.

[21] Lenin, Materialism and Empirio-Criticism, 329, also available at <www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1908/mec/six2.htm>.

[22] Werner Krauss, “Das Ende der Bürgerlichen Philosophie,” in Literaturtheorie, Philosophie und Politik, ed. M. Naumann (Berlin: Aufbau-Verlag, 1984), 505.

[23] Horkheimer, “Über Lenins Materialismus und Empiriokritizismus,” 186.

[24] Ibid, 186.

[25] Ibid, 187.

[26] Alfred Schmidt, “Unter welchen Aspekten Horkheimer Lenins Streitschrift gegen den ‘machistischen’ Revisionismus beurteilt,” in Max Horkheimer: Gesammelte Schriften, Vol. 11 (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Verlag, 1987), 424.

[27] Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, The German Ideology, cited in Horkheimer, “Lenin, Empiriokritizismus.”

[28] Horkheimer, “Lenin, Empiriokritizismus,” cited in Schmidt, “Lenin’s Streitschrift,” 425.

[29] Horkheimer, “Über Lenins Materialismus und Empiriokritizismus,” 186.

[30] Ibid., 187.

[31] Ibid., 187.

[32] Schmidt, “Lenin’s Streitschrift,” 425.

[33] Horkheimer, “Über Lenins Materialismus und Empiriokritizismus,” 188.

[34] Max Horkheimer, “Materialism and Metaphysics,” in Critical Theory: Selected Essays, trans. Matthew J. O’Connell and others (New York: Continuum, 1999), 35.

[35] Schmidt, “Editorische Vorbemerkung,” 172. Even while living in America, Horkheimer knew how to place a barely hidden reference to Materialism and Empiriocriticism in his English work Eclipse of Reason: “[T]he schools that call themselves empiriocriticism [!] or logical empiricism prove to be true varieties of old sensualistic empiricism. What has been consistently maintained with regard to empiricism by thinkers so antagonistic in their opinions as Plato and Leibniz, De Maistre, Emerson, and Lenin [!!], holds for its modern followers” [Eclipse of Reason [1947] (New York: Continuum, 1974), 78].