Understanding the Corbyn phenomenon: Context and prospects

Alec Burt

Platypus Review #91 | November 2016

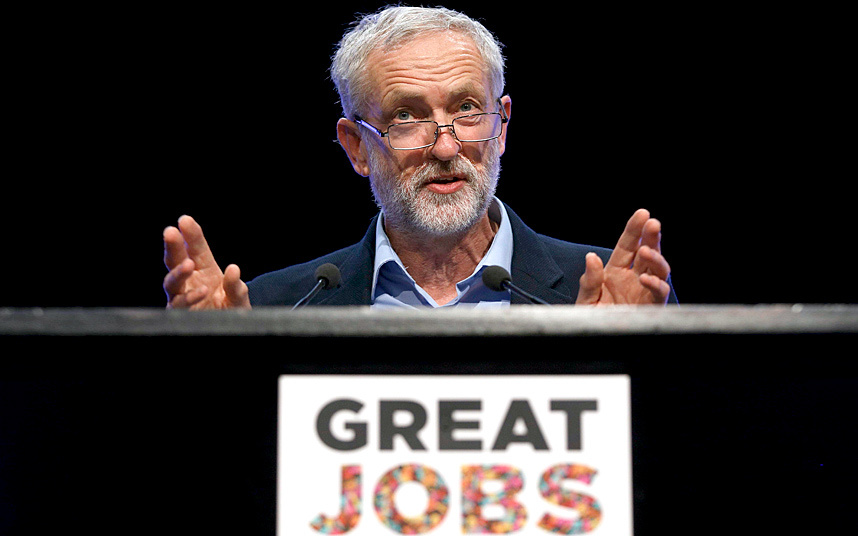

IN SEPTEMBER 2015, THE VETERAN RADICAL MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT Jeremy Corbyn defeated three other mainstream candidates to be elected leader of the UK Labour Party. He won over 250 thousand votes from members, registered supporters, and affiliated union members, 59 percent of the total. Corbyn was backed by most major unions, including Unite, the CWU, ASLEF, and UNISON.

During the first few months of Corbyn’s leadership, he enjoyed an uneasy peace with the 230 or so members of the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP, the collective organization of Labour’s members of the House of Commons), the vast majority of whom had little confidence in his leadership. This peace was shattered, however, in the wake of the shock result of the referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union held last June. In the turmoil that followed the leave vote, most of Corbyn’s Shadow Cabinet resigned and Labour MPs very publicly attacked their leader. These rebels were concerned by the prospect of an early general election, and convinced that Corbyn and his supporters had undermined the Remain Vote (despite Corbyn’s public support for staying in the EU).

Corbyn was challenged for the leadership by “soft left” MP Owen Smith. However, Smith’s campaign—despite being backed by the entire Labour establishment and all living former leaders—failed to persuade either the membership or the union leadership (with the exception of the GMB and USDAW). Corbyn was re-elected in September 2016 with an even larger mandate, securing 313 thousand votes and a majority of affiliated supporters, registered supporters, and members.

This essay attempts to place these results within an historical context and suggest how New Labour’s vapidity and the Financial Crisis facilitated this upset. As a recalcitrant Corbynista, I will offer my thoughts on how he can energize his leadership. In particular, I believe it is essential for him to move beyond the anti-austerity that catapulted him into the leadership, to form a more comprehensive programme for economic reform, one that we should articulate using aggressively populist rhetoric.

The historical context: Failure of the Labour Left

Since its foundation in 1900, the Labour Party has had a sizable leftist group. By “leftist”, I broadly mean those members and supporters who openly identified with being “on the left” of the Party, or were considered so by observers (for example, because they held policy positions that were considered “left-wing” by Party standards of the day, e.g. supporting unilateral nuclear disarmament).

Despite the left's regular conflicts with the rest of the Party, for nearly its whole history leftists have been excluded from the most senior positions, including the powerful post of “leader” (leaders are always either Prime Minister when the Party commands a majority in the House of Commons, or prospective Prime Minister when in opposition). Indeed, the history of the Labour left reads like a catalogue of failure.

Given the popular perception of the government of Clement Attlee (1945-1951) amongst British socialists—see, for example, Ken Loach’s The Spirit of ’45, a eulogy masquerading as a documentary—this may come as a bit of a surprise. Despite the undisputed successes of Attlee’s reforming administration, he was no radical leftist, as Ralph Miliband asserted with his characteristic vigor in Parliamentary Socialism. Attlee’s government did nothing to seriously reform the power structures of pre-war Britain. Despite the dream of bringing the commanding heights of the economy into public ownership, many industries, such as sugar and insurance, were never nationalized despite plans to do so. Those industries that were nationalized, such as coal, continued to be run by the same people who had run them before the war. The offspring of the country’s elite continued to be educated in Public Schools (an idiosyncratic English term referring to elite private “high schools” such as Eton College and Harrow School, Attlee was himself a former Public School boy). The City of London and armed forces—those twin bulwarks of the establishment—were buoyed by Chancellor Hugh Gaitskell’s huge rearmament programme (1950-51), which was funded partly by cuts to the new National Health Service.

The left was forced further into retreat following Labour’s defeat in the 1951 general election. For the rest of the decade Aneurin Bevan and his supporters faced defeat after defeat at the hands of Hugh Gaitskell (leader 1955-1963), who by the early 60s had achieved the majority of his objectives without, according to Anthony Crossland, “conceding an inch.”[i]

Following Gaitskell’s premature death, Harold Wilson (leader 1963-1976, prime minister 1964-1970, 1974-1976) spent most of his premiership placating the Party’s various warring factions without ever fully committing to any side. For example, he was able to side-step the thorny issue of the Party’s position on Britain’s membership of the European Economic Community (a Conservative government had taken Britain into the group in 1973) by holding a referendum on the issue and allowing his cabinet to campaign on both sides (Roy Jenkins et al. for remain; Tony Benn et al. for leave).

Michael Foot (leader 1980-1983) and George Lansbury (leader 1932-1935) were seen as coming from the left of the Party (for example, Foot was a Bevanite in the 1950s, a lifelong supporter of unilateral disarmament, and had campaigned for Britain to leave the EEC during Wilson’s referendum). However, both men drew support from across the PLP, with many rightists seeing their respective leaderships as necessary concessions. It is telling that Foot threw his weight behind Denis Healey when Tony Benn famously challenged him for the Deputy Leadership in 1981. This contest, which Healey narrowly won partly thanks to the decision of Neil Kinnock (later leader, 1983-1992) and other “left wing” MPs to abstain, is traditionally seen as the turning point in the “battle for the Labour Party” in the early 80s. By 1984 Kinnock—himself of South Wales mining stock—was refusing to support the National Union of Mineworkers in its infamous dispute with Margaret Thatcher’s government.

By the mid-1990s the Left had ceased to be a meaningful force in Labour politics. By the 2000s, left-wing activists (in the anti-capitalist, anti-free trade, radical environmental, and anti-war movements) were rarely members of the Party. For example, the veteran campaigner Peter Tatchell, who had been a high-profile Labour parliamentary candidate in the 1980s, left the Party in 2000 and joined the Green Party in 2004.

Those who remained failed to make much impact. Left-wing MPs John McDonnell and Diane Abbott both failed comprehensively in their respective leadership bids in 2007 and 2010. Tim Bale’s account of Ed Miliband’s leadership published just before the 2015 General Election made no reference to Jeremy Corbyn.[ii] Following Miliband’s resignation, McDonnell told supporters the “best [they] could hope for is a couple of weeks of trying to get on the ballot paper [prospective leadership candidates require a minimum number of nominations from Labour MPs to stand].”[iii] Corbyn, with a degree of reluctance, agreed to stand as a left candidate to, in his words, offer members “a broader range of candidates.”[iv] Corbyn only scraped onto the ballot paper. He did not expect to win.

It is also important to remember that the trades union movement, with some exceptions, has pretty consistently come out against the left during times of open Party conflict. As when, for example, the Communist Party of Great Britain attempted to affiliate with the Party during the 1920s. Or when Benn challenged Healey in 1981, or the leadership risked an embarrassing defeat over Iraq at the 2002 Party Conference.

It is vital, then, for us to try to understand how Jeremy Corbyn’s apparently remarkable victory came about. How this quiet, bearded man in his late 60s, who had never held ministerial office, achieved what Tony Benn and Nye Bevan could not.

New Labour and the origins of the Corbynistas

It would be impossible for me to offer a comprehensive explanation; instead, I hope to identify important contributory factors. First, the New Labour government (1997-2010)—undoubtedly one of the most right-wing European governments ever to have claimed the mantle of social democracy— pursued many policies that alienated and angered left-leaning people across the country.

The instances are well-known—the introduction and subsequent raising of university student tuition fees, for example. When, in contrary to an earlier promise, the government pushed through a rise in tuition fees in 2003, Labour Students (a New Labour vanguard) lost control of the National Union of Students’ presidency for the first time in a generation. Kat Fletcher, now a key Corbyn supporter, won that vote. At the time she the NUS conference “I've been a member of the Labour Party for many moons—but I've been let down repeatedly. I'm interested in finding an alternative to New Labour.”[v]

One mistake outshone all others, however: Iraq. Looking back from 2010, Jackie Ashley concluded that after the Iraq war “the Party was broken, below the skin, and has never healed … [u]ncountable numbers of decent people, in constituency parties, think-tanks and public life, lost heart and turned away.”[vi]

Needless to say, Jeremy Corbyn, a former chair of the Stop the War Coalition, was active in many campaigns that sprang up in opposition to New Labour.

Disconnect with New Labour was about more than policy, however. New Labour’s spin-heavy and autocratic approach to government and Party management put off large numbers of supporters. Conference became a stage-managed week of sound bites, delegates were carefully vetted, votes planned in advance. MP selection—although nominally the responsibility of local members—was carefully managed so that candidates favored by the leadership were well positioned for success. In the run up to the 1997 General Election, Leeds North East constituency Labour Party (CLP) selected Liz Davies, associated with the left-wing Labour Briefing, as their candidate. Tony Blair was furious and the National Executive Committee (NEC) overruled the decision.[vii] The Party would later introduce a National Parliamentary Panel to vet potential candidates to ensure the Davies situation was not repeated.

This system could also function in reverse. When David Miliband was planning on leaving Tony Blair’s office, a Millbank (Millbank Tower, south of the Palace of Westminster, was site of the Party’s headquarters for much of this period, and the 1960s skyscraper became synonymous with the New Labour machine) official Margaret McDonagh was assigned the task of finding Miliband a House of Commons seat. Within a few months, David Clarke, MP for North Shields, had suddenly announced his retirement and Miliband was selected for the seat despite having few connections with the area. After the election Clarke was elevated to the peerage, a common conciliation to MPs who were asked to step aside by New Labour mandarins.

The rationale for the system of selection was explained by New Labour apparatchik David Gardener, “[w]e are a broad church. But we also want candidates we can rely on to sustain Labour in power.”[viii] Andrew Lawnsley explained that “[i]n the Blairite conception of parliamentary democracy the role of New Labour MPs [was] to sustain the Government.”[ix] New Labour was willing to tolerate the likes of Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell addressing anti-war rallies as vivid reminders of the dark past New Labour had emerged from, but nothing more.

The effect of these changes was to drive many members—uninspired by New Labour’s heavy reliance on business marketing techniques, and no longer convinced that they could have any real impact on decisions—out of the Party. During the New Labour years the Party hemorrhaged support. Between 1997 and 2006 the Party lost half its membership. Lewis Minkin concluded that many of these left because of perceived lack of influence (e.g. in policy making or candidate selection).[x]

Those who remained agitated for change. I myself was briefly involved in one such campaign when my university Labour Club, along with ten others, voted to disaffiliate from Labour Students (LS) . Many of us had long been campaigning for democratic changes in how the organization was run—in particular greater use of “One member, one vote”. We felt the previous delegate-based system rendered LS little more than an oligarchy, tightly controlled by a small Blairite clique. After the LS leadership blocked moves to debate a change in the voting system at the conference in 2014, we decided to disaffiliate.[xi]

It is worth noting, of course, that New Labour could always count on a degree of backing while it was able to win elections and, in the words of Liz Kendall, Owen Smith et al., “put our principles into action.” However, following the defeats in 2010 and 2015, when millions of “safe” Labour voters abandoned the party for UKIP and the SNP, radical supporters became increasingly unconvinced even by this argument.

Corbyn and anti-austerity

There was one factor, however, that really changed the game: “austerity”. In his recent analysis of the origins of the Eurozone crisis, Yanis Varoufakis noted how Europe’s social democrats embraced neoliberalism and financialization and in return were “lulled into a haze of mythological faith, ... where a mystery goose would lay increasing quantities of golden eggs from which the welfare state, which remained the sole surviving connection with their conscience, could be financed.”[xii] Nowhere was this truer than in Britain, where—in return for, in the words of Tariq Ali, continuing “Thatcherism by the same means”[xiii]—the New Labour government was permitted a share of the City’s ballooning profits to fund badly-needed investment in Britain’s welfare state.

However, as Varoufakis also notes, when tax revenues from the financial services industry disappeared in the wake of the Financial Crisis, and governments felt compelled to bail out failing banks, Europe's social democrats “did not have the mental tools, or the moral values, with which … to subject the collapsing system to critical scrutiny … [they were] ready to … bow their heads to the bankers’ demands for bailouts to be purchased at the price of self-defeating austerity for the weakest.”[xiv] Put simply, the whole raison d'etre of Europe’s new generation of social democrats vanished with the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008, but by then none of them knew anything different.

The 2015 Labour manifesto promised to match the Conservative fiscal plans. Even then, in the wake of Labour’s defeat, potential candidates for the leadership attempted to outdo each other in abandoning the few progressive elements of that manifesto. By embracing frankly savage austerity, the mainstream of the PLP dealt itself a fatal blow. Members—many of whom may have experienced the reality of austerity firsthand or witnessed its effects on families, friends, or colleagues—were simply unprepared to support a leadership candidate promising more of the same.

Reading the debates from last year’s campaign and before, the word “austerity” appears again and again. For example, Green Party's 2015 Party election broadcast featured four actors (representing the four main Party leaders) singing “It's sweeter when we all agree / A Party political harmony … Austerity! / Austerity! / Austerity! / Austerity!” A search of “austerity” produces 17,700 results on the New Statesman website. Jeremy Corbyn himself acknowledged in an interview with Red Pepper magazine that “[t]he whole basis of the [2015] campaign was anti-austerity.”[xv]

In particular, anti-austerity was crucial in persuading union bosses to support a leftist candidate. One of the first suggestions that an upset might be in the offing during the summer of 2015 was when UNISON, which represents over one million public sector workers, decided to endorse Corbyn. As the New Statesman noted at the time “[t]he development is still something of a shock within Labour circles, ... Unison is … regarded as representing the centre of the Labour Party. ‘ one MP once remarked to me: public sector, soft-left, not antagonistic towards the New Labour era but not nostalgic for it either.”[xvi]

UNISON’s members were furious at facing, not only, the pressure of working in organizations that were being asked to find huge savings, but also at being subjected to years of pay freezes. Freezes that Labour endorsed in the years before the 2015 General Election. The union’s General Secretary argued at the time “Jeremy Corbyn’s message has resonated with public sector workers who have suffered years of pay freezes and redundancies.”[xvii]

Even the language of the debate played a part. Paul ‘t Hart wrote in 1993 that “[t]he most important instrument of crisis management is language. Those who are able to define what the crisis is all about also hold the key to defining the appropriate strategies for [its] resolution.”[xviii] The rhetoric employed during the fiscal or “austerity” crisis severely disadvantaged the “moderates” in the Party. The left has successfully used the term “austerity” to draw a stark dividing line between those who were apologists for the modern capitalist system and those, like Corbyn, who were not.

Corbyn’s leadership so far

So where does this leave Jeremy Corbyn? His future prospects are mixed. Having spent years as a backbench MP, Corbyn has found it difficult to adapt to the realities of running a major political party. At times the leadership has seemed paralyzed by a mixture of paranoia, inexperience and confusion—decisions going unmade, shadow ministers left without direction, media messages bungled.

Naturally, Corbyn has faced and will continue to face huge obstacles. There have been Labour MPs who have undermined him at every turn, some individuals have never missed an opportunity to parade across the TV screens filled with faux outrage at the latest artificial drama. Of those 172 who voted no confidence in Corbyn’s leadership at the beginning of the summer, many will find it impossible to admit they were wrong and openly reconcile themselves to a very different kind of Labour Party.

The media, including the Guardian, has been at best apprehensive and at worst actively hostile, towards Corbyn, more than happy to spread negative rumors or dwell with glee on any and all mistakes.

It is, of course, unfair, but wholly predictable under the circumstances. Someone as radical and anti-establishment as Corbyn is inevitably going to face significant opposition. The ruling class will not surrender the gains they have made under neoliberalism easily.

Consequently, to stand a chance of electoral success, a radical opposition leader has to be a ruthlessly efficient political operator. There can be little room for error in the face of an establishment onslaught. Luckily there are some positive indications that Corbyn is beginning to settle into the leadership role, certainly his conference speech this year was a noted improvement on the previous year.

Suggestions from a recalcitrant Corbynista: Clever of head, crude of mouth

So what should be Corbyn’s strategy going forward? I would make four broad suggestions: seek to further democratize the Party but without engaging in “open warfare”; actively marginalize surviving traditional far-left organizations; develop a radical, innovative, and intelligent policy programme; and learn to articulate that programme using aggressively populist language.

Corbyn has hundreds of thousands of loyal supporters within the Party. Moves to further democratize the Party machine (by, for example, increasing the power of conference) will inevitably lead to the gradual evolution of Labour from “clique-en-masse” to a powerful socialist movement controlled by its members.

We should, however, resist the temptation to take out our anger on “right-wing” Labour MPs by moving to deselect them (see James Marshall’s recent piece in the Weekly Worker ).[xix] There is a reason why many of the right of the Party have been mentioning deselection repeatedly in the media; they are itching for a fight, for a chance to show “the trots for what they really are”. Instead Corbyn’s approach to the PLP should be “divide and rule”, bringing the soft left into the fold, isolating the “core group negative” and starving them of oxygen.

Greater democracy—by, for example, utilizing electronic voting to bypass the stuffy atmosphere of local meetings—also has the added benefit of aiding in my next suggestion: marginalizing traditional far-left organizations. Something exemplified by a recent row in Momentum (a pro-Corbyn pressure group). The Alliance for Workers’ Liberty (AWL) and other organizations were furious when the movement’s leadership decided to introduce an all member electronic voting system for its conference in January. Far-left organizations like the AWL know that a traditional system of branch meetings, delegates, block votes, central committees etc., allows small but disciplined groups of activists to take control of much larger organizations such as Momentum.

In The Road to Wigan Pier George Orwell bemoaned “the horrible—the really disquieting—prevalence of cranks wherever Socialists are gathered together.”[xx] On a broader level, we cannot let this new movement, which has engaged so many people previously uninterested in organized politics, be hijacked by the “cranks” of the AWL or Socialist Workers’ Party (SWP). Not only have these groups failed to demonstrate that they are capable of achieving any meaningful political success, they also regularly court controversy and in doing so risk discrediting Corbyn’s Labour Party.

Take, for example, the SWP, which has thrown its “weight” behind Corbyn, happily distributing placards at his rallies. The SWP’s leadership destroyed what little reputation their movement still enjoyed by their unjust and offensive handling of a series of rape allegations in 2013. It is not clear if this “Party” has achieved anything in its forty year history, apart from widespread and justified contempt. Certainly, its electoral performance has been laughable. It is part of the Trade Union and Socialist Coalition, one of whose candidates managed to get zero votes (he could have voted for himself) in a Kent local government election in 2015. We have no need for such people.

As noted above, Corbyn’s anti-austerity message allowed him to galvanize support from across the left. It would, however, be a mistake to think that we can use the same message to win a general election or that anti-austerity can form the basis of a truly radical economic programme. Unfortunately Corbynomics remains primarily concerned with building an adequately funded and comprehensive welfare state. Important though this objective is, we cannot limit our ambitions to returning to pre-2010 spending levels. You cannot tax and spend your way to a fundamental realignment of the relationship between capital and labour. Marshall is right to heap disdain on the editor of the Morning Star Ben Chacko whose “sights are set on ‘saving an A&E or a youth club.’ That he does so in the name of Marxist politics and creating a mass movement on the scale of the Chartists shows an inability to grasp even the A in the ABC of communism.”[xxi]

The first step is to clearly define what our key economic aims are, at least in the medium term. Some examples of these aims might be: stability, a greater equality in the distribution of wealth and income, employees having a far more important role in the running of businesses (e.g. economic democratization ), labour-saving technologies benefiting the workforce as a whole instead of just capital, and economic growth that is both environmentally and economically sustainable.

The second step would be to be open-minded about how to achieve these aims. With state ownership of industry and state planning now so widely discredited (and understandably so) we cannot afford to be exclusive. There is value to be found in the “Varieties of Capitalism” school that so influenced Ed Miliband, the Keynesian ideas of Joseph Stiglitz and Paul Krugman, Yanis Varoufakis’s plans for global monetary reform, and the more radical market socialism of the likes of Richard Wolff.

We should not be scared of articulating this radical intelligent programme with a degree of crudeness, however. Our message to the UK population must be unashamedly populist, learning from the successes (and failures) of our comrades in Latin America, Greece and elsewhere. We should seek to, in the words of Yannis Stavrakakis, use a “popular-democratic egalitarian grammar,” where “the people” are our “nodal point”. We should present ourselves as uniquely placed to “voice [the people’s] grievances and demands.” The image of Britain we must conjure is, to paraphrase Benjamin Disraeli and his unlikely reincarnation Ed Miliband, of “two nations”: “the establishment, the power bloc versus the underdog, the people.”[xxii] The ascetic, quietly-spoken and modestly-dressed Corbyn is well suited to such a rhetoric.

Either we on the left take up the arms of populism, or we risk leaving them at the disposal of a right-wing demagogue, someone in the shape of Nigel Farage or Donald Trump.

Hopes for the future

Enrique Oltuski — an anti-Batista, but also anti-Castro political activist in pre-revolutionary Cuba—remarked upon meeting Ernesto “Che” Guevera that “[i]n spite of everything … one can’t help admiring him. He knows what he wants better than we do. And he lives entirely for it.”[xxiii] Although, Jeremy Corbyn is, of course, not really comparable to Che Guevera (he has a far greater respect for human rights for example!), there is nonetheless something about this quote that reminds me of Corbyn. He has a clarity of vision, an unwillingness to ignore the barbarism of modern capitalism and war that I have a huge respect for.

A remarkable collection of forces have coalesced to put him in Labour’s driving seat. The onus is now on Corbyn, his team, and supporters to grasp this opportunity with both hands and exploit it for all its worth. Whether Corbyn’s leadership heralds a paradigm shift in British politics or ends up being the last hurrah of a dying leftist movement remains to be seen. I so wish it to be the former, but we shall have to wait and see.|P

[i] Quoted in Keith Laybourn, A century of Labour: A history of the Labour Party, (Stroud: Sutton, 2000), 104

[ii] Tim Bale, Five year mission: The Labour Party under Ed Miliband, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015)

[iii] John McDonnell quoted in The Corbyn Story, aired 13 July (London: BBC Radio 4, 2016), radio broadcast

[iv] Quoted in Joos Couvee, “Corbyn set to run for Labour leadership”, Islington Tribune, 3 Jun, 2015

[v] Quoted in Sam Caldwell, “Labour loses its grip as NUS joins the awkward squad”, Socialist Worker, 10 Apr 2004

[vi] Jackie Ashley, “here lies New Labour—the party that died in Iraq”, The Guardian, 31 Jan 2010

[vii] Jonathan Foster & Patricia Wynn Davies, “Labour may be sued for dropping left-winger”, The Independent, 28 Sept 1995

[viii] Quoted in Lewis Minkin, The Blair Supremacy (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014), 394

[ix] Ibid, 428

[x] Ibid, 718

[xi] See “11 University Labour Clubs threaten to disaffiliate from Labour Students over OMOV”, Labour List, 20 Feb 2014

[xii] Yanis Varoufakis, And the weak must suffer what they must, (New York City: Nation Press, 2016), 214

[xiii] Tariq Ali, The Extreme Centre, (London: Verso, 2015), 20

[xiv] Varoufakis, And the weak must suffer what they must, 214-215

[xv] Quoted in Hilary Wainwright and Leo Panitch, “An interview with Jeremy Corbyn”, Red Pepper, Dec 2015

[xvi] Quoted in Stephen Bush, “Why has Labour’s “swing voter” endorsed Jeremy Corbyn?”, New Statesman, 29 July 2015

[xvii] Quoted in Nicholas Watt, “Unison endorses Jeremy Corbyn for Labour leadership”, The Guardian, 29 July 2015

[xviii] Paul ’t Hart, “Symbols, rituals and power: The lost dimensions of crisis management”, Journal of contingencies and crisis management, 41

[xix] James Marshall, “How to win”, Weekly worker, 29 Sept 2016

[xx] George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier, (1937)

[xxi] Ibid

[xxii] Yannis Stavrakakis, “Populism in power: Syriza’s challenge to Europe”, Juncture, (2015)

[xxiii] Quoted in Jon Lee Anderon, Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life (London: Bantam, 1997), 356