Book Review: Doug Henwood, My Turn: Hillary Targets the Presidency

New York: OR Books, 2016.

Gregor Baszak

Platypus Review #83 | February 2016

“My two cents’ worth—and I think it is the two cents’ worth of everybody who worked for the Clinton Administration health care reform effort of 1993–1994—is that Hillary Rodham Clinton needs to be kept very far away from the White House for the rest of her life… Perhaps she will make a good senator. But there is no reason to think that she would be anything but an abysmal president.” With this epigraph, a quote by Brad DeLong, former Undersecretary of the Treasury during Bill Clinton's first term, Doug Henwood opens his short but effective takedown of Hillary Clinton: My Turn: Hillary Targets the Presidency. According to Henwood, DeLong has since then deleted the archives of the blog on which he had originally posted this warning and has refused to respond to Henwood's inquiry on whether he still believes it. The suggestion is: one wouldn't want to lose a Clinton's favor if one wants to have a shot at one of the lucrative Special Government Employee positions that Hillary apparently handed out unlike anyone before her as Secretary of State, most often to old associates who had proven uncompromisingly loyal to either of the Clintons. In turn these associates are able to exploit their status for their personal benefit (72 et seq.).

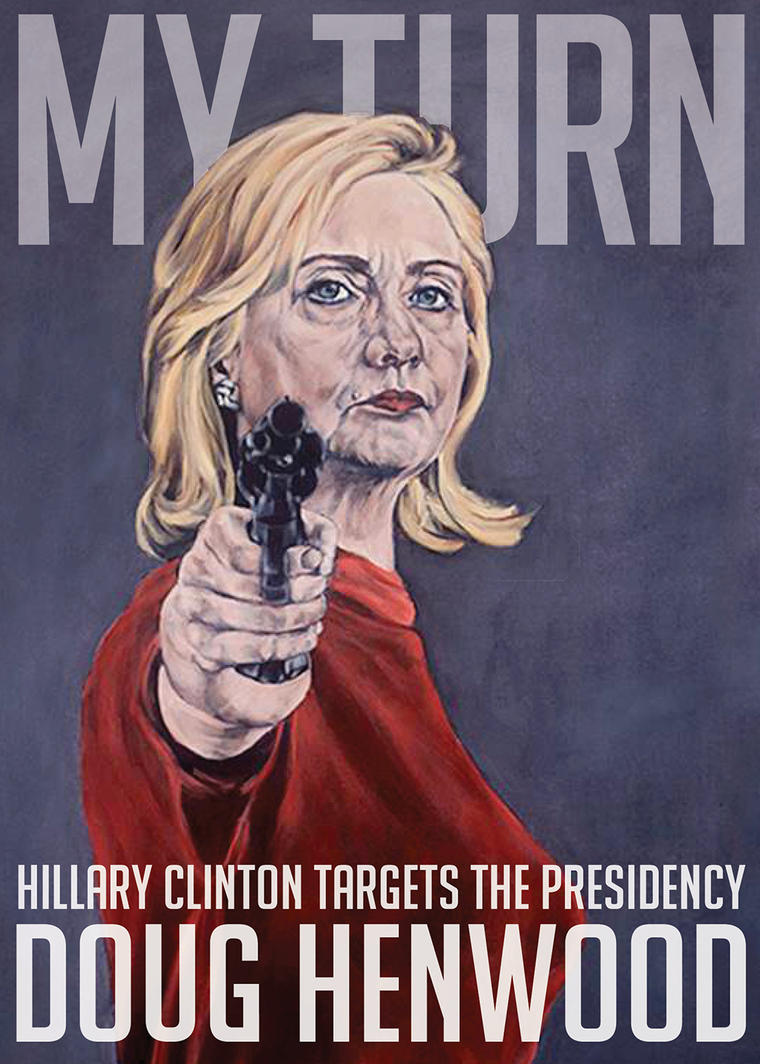

Cover of Doug Henwood’s My Turn

Politics as a personal racket—no one has perfected this science better than the Clintons, a power couple that decided very early in their political careers on what they deemed “The Journey,” that eight years of Bill's presidency would inevitably be followed by eight years of Hillary (39–40). Since their origins in a petit-bourgeois suburban community in Illinois (Hillary), and a working-poor family in Arkansas (Bill), the Clintons' stints in politics, in “philanthropy,” and on the generously compensated speaking circuit have allowed them to amass significant fortunes: Bill is now “the 10th-richest of our presidents, with a net worth of $55 million . . . But Hillary wasn't just sitting around baking cookies: she's worth $32 million” (96).

As the book's title suggests, Hillary's claim to the throne comes out of a sense of personal entitlement, and that she has not much more to say in her favor than “she has experience, she's a woman, and it's her turn” (14). Henwood notes that Hillary's own political career has been harmless at best, resulting in just minor achievements as Senator from New York (53) and as Secretary of State (65). As a matter of fact, the latter title seems to have been handed to Hillary purely as a gesture of peace after the contested 2008 primaries and has come with little responsibility—the majority of major foreign policy decisions were instead made by a circle of close Obama associates in the Oval Office. (( See also: Daniel De Luce, “Hagel: The White House Tried to ‘Destroy’ Me,” Foreign Policy, Dec. 18, 2015, <http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/12/18/hagel-the-white-house-tried-to-destroy-me/>. )) At worst, Hillary's political career has been continuously one of personal enrichment and shady public-private deals cut with the help of her husband, on the edge of illegality (32). Furthermore, she helped to slash welfare (42–3) and advocated for the 1994 crime bill that caused “the incarceration boom that she now says she's against” (120) during Bill’s presidency, (( See also: Gregor Baszak, “Marxism through the back door: An interview with Cedric Johnson,” Platypus Review 79, Sept. 2015, <http://platypus1917.org/2015/09/01/marxism-back-door-interview-cedric-johnson/>; and John P. Walters, “Rand Paul Attacks Hillary Clinton on Criminal Justice for African Americans,” Weekly Standard, May 19, 2015, <http://www.weeklystandard.com/rand-paul-attacks-hillary-clinton-on-criminal-justice-for-african-americans/article/950424>. )) and assisted in expanding “U.S. imperial ambitions” as Secretary of State (77).

Interestingly and fortunately, however, Henwood extends his criticism beyond Hillary Clinton. He begins the book by echoing Sarah Palin's absolutely fair ridicule of the empty rhetoric of “hope” and “change” that had brought the Chicago Democratic machine politician Barack Obama to the presidency in 2008. According to Henwood, Obama's presidency can be summarized as in many ways as bad as that of his predecessor, George W. Bush (13), and in some other ways—such as Obama's cutting funds for Bush's much-praised federal anti-HIV efforts (109)—worse than it. Drawing on Walter Benn Michaels, Henwood refers to Obama's brand of politics as “the left wing of neoliberalism” (14): in either case, “you get rule by a moneyed elite, but the left variety is more attentive to optics” (84). In other words, in terms of economics and foreign policy there is not much difference between the Democrats and the Republicans, but the former certainly care more about positioning themselves as liberal in terms of social issues such as gay rights. (( Cf. Chris Cutrone, “The Sandernistas: The final triumph of the 1980s,” Platypus Review 82, Dec. 2015, <http://platypus1917.org/2015/12/17/sandernistas-final-triumph-1980s/>; but see also Yasmin Nair, “Gay Marriage IS a Conservative Cause,” YasminNair.net, Feb. 26, 2013, <http://www.yasminnair.net/content/gay-marriage-conservative-cause>. )) As liberal outlets such as Salon and Slate have rallied firmly around Hillary so far, and in their cute and starry-eyed way have begun to admire the candidate's ostensible “left” turn, Henwood finally concludes that this “is further proof that Democrats, especially liberal Democrats, are the cheapest dates around—throw them a few rhetorical bones, regardless of your record, and they're yours to take home and bed” (119).

Unfortunately, Henwood doesn't extend his criticism of the Democratic Party as such much further than that. He instead ends the book on promising criticism of such movements and social media campaigns as Occupy and Black Lives Matter. The latter Henwood takes as “characteristic of so much dissent today: more about self-affirmation and healing than about taking power” (135). However, what the organizational form of an actual attempt at seizing power by the Left should be, he leaves unanswered. Perhaps intentionally so: as Henwood acknowledges from the outset, Hillary isn't “The Problem,” but rather “a symptom of a deep sickness in the American political system,” which he then traces back to Constitutional checks on popular power, the two-party system, and the influence of elites in politics and the economy (19). Thus, he admits, his book on the presidential candidate Clinton at the same time is meant as a warning against exaggerating the “political importance of presidential elections” (20). But all this leaves him with is the vague argument that “anyone who wants a seriously better politics in this country has to start from the bottom and work their way up” (21). This is also why Henwood hesitates to make a full endorsement for the sort of politics Bernie Sanders represents. “If, by some freakish accident, Sanders ever got elected,” Henwood writes, “the established order would crush him. We'll never find salvation, or even decency, from above” (21). Such a statement is more a platitude than trenchant political analysis, since it poses politics as a simple conflict between those “above” and those “below.”

Hopeless or not, however, Henwood sees such a more genuinely left challenge and thus possibility in the candidacy of Bernie Sanders, irrespective of his qualifiers that Sanders' foreign policy—especially his stance on Israel—is problematic (118), and that he is less a socialist than a social democrat (119). For Henwood, the Sanders campaign proved “a jolt of life” for a primary season that would have been otherwise no race at all (140). (( Cf. Joseph M. Schwartz, “Bernie Sanders Can Help Revitalize the American Labor Movement,” In These Times, Sept. 9, 2015, <http://inthesetimes.com/working/entry/18388/bernie-sanders-unions-labor-movement>. )) Predictably, though, the major unions have already backed Clinton, certainly so as not to alienate the party establishment in the future. The AFL-CIO, SEIU, etc. place themselves at the mercy of a party whose own pro-union commitments are a remnant of the New Deal coalition. These commitments, however, have diminished drastically over the last few decades, not only under Clinton's reign, but much earlier, under the Carter administration. (( See Judith Stein, Pivotal Decade: How the United States Traded Factories for Finance in the Seventies (New Haven: Yale UP, 2010). ))

This is perhaps why underlying the Left's support of Sanders is a hope to return to the seeming strength of the American labor movement in the immediate post–WWII era. Why this would be a triumph for the Left is unclear, though. The major unions were deeply embedded in the Democratic Party's Cold War liberalism, and played more the role of a racket reaching for its cut from the national surplus product than many leftists would have it. (( Cf. Max Horkheimer, “On the Sociology of Class Relations” (1943), Nonsite, Jan. 11, 2016, <http://nonsite.org/the-tank/max-horkheimer-and-the-sociology-of-class-relations>. )) The excitement for Sanders, therefore, looks misplaced and is reminiscent of earlier proxy candidates that the American Left placed its hopes on, for instance the young Communist movement's uncritical support for the populist Republican senator Robert La Follette. In reaction, Leon Trotsky warned in 1924 of “the political dissolution of the party in the petty bourgeoisie,” losing its distinct character as a party for international socialism. “After all,” Trotsky concluded, “opportunism expresses itself not only in moods of gradualism but also in political impatience: it frequently seeks to reap where it has not sown, to realize successes which do not correspond to its influence.” (( The First Five Years of the Communist International. Vol. 1. (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1972), p. 13. )) The Communist movement soon after submitted to President Franklin Roosevelt's anti-cyclical investment measures, which he distinctly presented as an attempt at limiting the reach of more radical challenges to the status quo of American society. (( See his 1932 acceptance speech at the Democratic Party convention: <https://fdrlibrary.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/1932.pdf>. ))

On the whole, then, the book misses a great opportunity: to understand Hillary as a symptom to be sure, but less as one characteristic of a centuries-old American political order, and instead as one of the demise of the American Left in the 20th century—its liquidation into the Democratic Party. It might have been the journalistic “jolt of life” this primary season needed, but which My Turn ultimately didn't become. Rather, it is a useful compilation of facts and figures showing that the label “lesser evil” doesn't apply when it comes to Hillary Rodham Clinton—she “needs to be kept very far away from the White House” indeed. But the Left appears to be on the path back into the arms of the Democratic machine once again. Perhaps this calls for a book that instead stresses that the Left must be kept very far away from the Democrats. |P