“A new world racing towards us”: An interview with Bill Ayers

Spencer A. Leonard

Platypus Review 62 | December 2013–January 2014

On October 28th, Spencer A. Leonard interviewed Bill Ayers, former member of Students for a Democratic Society and the Weather Underground and author of the memoirs Fugitive Days (2001) and Public Enemy(2013). What follows is an edited transcript of their conversation.

The Weather Underground symbol on the cover of Prairie Fire. About the letters to police and journalists that would accompany Weather Underground bombings in the 1970s, Ayers writes in Fugitive Days, “Each letter had a logo hand-drawn across the page–our trademark thick and colorful rainbow with a slash of angry lightning cutting through it. New morning, it signified, changing weather.” (235)

Spencer Leonard: In the 2008 “Afterword” to the first installment of your memoir Fugitive Days, you write, “I just saw a bumper sticker with a large colorful peace sign – all tie-dyed and psychedelic, so sixties – with an accompanying slogan: BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND. And on the radio John and Yoko implore us: ‘All we are saying is give peace a chance.’” And on this observation you comment simply, “Déjà vu all over again.” You then go on to say that, “in some ways the mythologizing of the 1960s is now a brake on progressive struggles.”[1]

The post-reelection, post-Occupy moment we now inhabit seems quite distant from 2008. Looking back, what about the post-9/11 period seemed to provoke the 60s déjà vu you speak of in the “Afterword”? How has the legacy of the 1960s, its “mythologization” as you put it, become an obstacle to the possible reconstitution of the left in the present?

Bill Ayers: One reason I wrote “Déjà vu all over again” relates to the notion of permanent war, the experience of “Here we go again!” where the issue of war, invasion and occupation is concerned. I mean it is just never ending. For people who like to think of themselves as peace loving, we are never without war. We are a warlike, highly militarized, deeply violent society. People hate hearing that, but it’s true. And we have never been able as a country to come to grips with the wars we’ve involved in. Because we make no honest accounting of them we continue to be mesmerized and mythologized right back into the next war. That is what I mean about déjà vu.

SL: One of the things I was trying to get at is the way the memory of the 60s lingers now in a way that perhaps the 30s didn’t linger for you. The heroic days of the Old Left, the 30s formed an immediate background for your generation, and ultimately the New Left had its reckoning with the Old Left: You came to terms with it at some level. So, why does this generation have to constantly look back to the 60s just as did those politicized in the 1980s and 1990s? What, if anything, does this tell us about the crisis we face?

BA: There is a great deal of mythologizing of “the 60s,” but for me “the sixties” is so much myth and symbol. Nobody I know lives by decades. Nobody looked at a clock or a watch on December 31st, 1969, and said, “Oh crap! It’s almost over!” Nobody did that then and nobody does that now.

If you look at any cut of the last hundred years, you see that the 1960s is really a continuation of the post-World War II period. There wouldn’t have been a Civil Rights movement without the struggles within the military and, later, the struggles of the returning Black GIs and so on. So we have to be careful about this idea of “the 60s.” When did it actually start? 1954, 1966? When did it end? 1978? Now? I remember a Newsweek story in 1968 that asked, is the 60s over? This was even before the Columbia Revolt, before the Tet Offensive, before Mexico City. So, this mythmaking is crazy. Young people are fed a steady diet of “In the 1960s the demonstrations were perfect, everyone agreed to oppose the war, racial justice was on the agenda, it was righteous struggle everyone engaged in, they had the greatest music and the best sex.” This ideology is poured into people to instill a sense of the inadequacy of the present. I can’t tell you the number of times people have said to me when I am speaking or doing a book reading, “Gosh, I was born in the wrong generation.” As if coming of age in the 60s was a guarantee of righteousness and ecstasy? It’s all marketing and that is not real. If want to get real about building a Left, we have to put the 60s in perspective and into a continuous line with today. That’s one thing.

That said, I don’t buy the generational way of talking of struggle. I don’t believe that my generation is the generation of the 60s. I am attuned to the present, ignited by the same passions and focused on the same commitments—peace, racial and economic justice, education as a great humanizing enterprise— that flared up inside and all around me 50 years ago. I still look uncomfortably at the world we are living in. This is perhaps something I think of as I get older, but everyone I saw in the street today from babies in carriages to old people with canes, everyone of us will be dead in 100 years. And aren’t we sharing the planet right now? I think it does not do us much good to say I was of that generation. I am not done. And so I choose to be of this generation.

SL: Certainly, the last thing we need to do is to divide ourselves in those terms. But I am interested in the possible transmission of historical experience in such a way that allows history to be transformed.

BA: I think that there are things to discuss and things to learn from the experiences of, say, the 1968 upheaval. The one thing not to learn is that it was perfect and that everybody knew what to do. That is far from true. More generally, I would say that the large matters that still haunt our culture from the 60s are the Vietnam War and the Black Liberation Struggle. These are two critical issues unfolding, and being contested in that period and, in both cases, we have not come to terms with the meaning of what happened: What people tried to do, what they failed to do, and where that leaves us today. I write about this in Public Enemy: There has never been a truth and reconciliation process. I don’t mean some committee, and I don’t mean that we could reach an uncontested or untroubled end point. Still, we have yet to look into the Vietnam War and the opposition to it and ask: What is true about that experience? One obvious indication that we have never done that is that John McCain could run for President as a Vietnam War hero; in fact, John McCain is a war criminal. Yet nobody in the mainstream media ever challenged him. Nobody ever said, “Oh my God! You committed despicable acts of terrorism in a genocidal war.”

So, we have never had anything like a truth and reconciliation process. We have never gone on that quest together. We have never looked for the truth, we have never tried to dig for all the facts. And because we’ve never tried, Vietnam haunts us. What’s fascinating is that, if you go to Vietnam, it doesn’t haunt them. They are all done with their American war. It’s ancient history; they don’t need to worry about it so much. It’s no longer a reference point for them moving forward and backward, it casts no dark and murky shadow. But it does for us because we’ve never collectively faced it with open hearts and open minds. Frankly, you can say the same thing for the Black Freedom Movement. The dominant narrative is, “We won!” Now everything is post-racial: Obama stands at the end of the Selma Bridge. Martin Luther King had a dream, that dream has been realized, and we are all so much the better for it. It’s a lie. It is why people like Dick Cheney can sit down to the Martin Luther King breakfast without suffering indigestion or second thoughts. It is an insanity, but a collective insanity. We can’t see the ways in which the racial nightmare has transformed itself. White supremacy continues. It has never gone away. Since we don’t want and don’t know how to face that, we lie to ourselves and mythologize the struggles. This weakens our capacity to move forward in hopeful and deliberate and positive ways.

SL: Part of what I read out of your discussion of the déjà vu feeling of the recent antiwar movement is that the Left doesn’t really engage history in our time. For this reason, I want to address history’s seeming anemic and reeling condition occasioned by the deep crisis of the Left and to get at that by asking how your generation faced a somewhat comparable problem in the process of your becoming politicized. Certainly, the New Left had to confront much that rang false in the legacy it inherited in that you faced on the one hand, a triumphalist welfare statist liberalism that claimed to be gradually including within its promise all that stood outside it, and, on the other hand, the legacy of the Communist Party, which, in order to claim that, so to speak, history was proceeding according to plan a great deal had to be fudged or lied. You had perhaps more sympathy with the Communist Left than with the Liberal Left at certain points, but at all events the New Left waded into history despite those lies and distortions. So, it seems to me that this question of the Truth and Reconciliation about Vietnam is really tied into the question of reconstituting our Left in the world today. You’re suggesting that we are not really going to refashion the Left for our time until and unless we have generated a certain honesty about the past.

BA: I think that’s true. Political honesty about the past is needed. It is not a question about getting the right answer but of engaging collectively in a quest, one that will include lots of complexity and contradictions. At least we will have it out in the open. Look at South Africa, a society that tried very hard to face its past. Did it come out pure, good, and perfect? Is there one single story? No, there is not. It didn’t accomplish everything it set out to accomplish, but there is something in that model that is very compelling to me. It is true that when I was a young person first coming to politics out of a very privileged background, my comrades and I waded into history. There were critical things going on just then. Most compelling was the mass upheaval from below, the Black Freedom Movement. It defined the moral landscape and the political moment. We didn’t choose that. We didn’t initiate or organize it. We didn’t get to define that, but we found ourselves within it trying to work our way out. I’ll never forget that the Old Left, many people on the Old Left, including Michael Harrington, Irving Howe, and many Communists, looked at the sit-ins and the Freedom Riders and said, “Ugh, those guys are a bunch of action freaks. They have no ideology! Don’t pay much attention to them.” But to us, who were young and ready to go, that was a kind of primal mistake. You are looking at the Paris Commune and saying, “Ah, stupid, just a bunch of action freaks.” (Students Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and others were setting the terms and the agenda. The fact that the organized Left at the time couldn’t see it or couldn’t come to terms with it struck us as fatal. So we created groups like Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). What was the SDS? It was a group that said, we must dive into the wreckage, engage in the activism and find out who we are and where we stand by joining the struggle. We had two guiding principles: One was align yourselves with the most oppressed; the second was learn what to do by acting on the world not by sitting in the armchair and thinking about the world, which we thought Michael Harrington was doing. No, we had to act on the world; we were impatient. We could not stand the Kennedys and the Democratic Party. We were impatient with the socialist left and absolutely flabbergasted by the Communist Left. We didn’t want to be Communists in that sense. So we called ourselves small “c” communists and created what we called the New Left. The New Left had the great strength of not being weighed down by the chains of the communist experience of the twentieth century, but its great weakness was its unwillingness or inability to learn from history. That was a contradiction. Both were true: We didn’t feel the weight of that history, nor could we learn from that history and that was fatal also.

SL: Let me ask about ideology, because, of course, eventually (beginning in the late 1960s) the New Left had its confrontation with Marxism and the legacy of the Old Left. For instance, speaking of the early formation of the Weather Underground in Fugitive Days, you mention someone you term CW, someone who “found the movement through his involvement with a tight little leftist sect he’d joined as a teenager.” Because of this background, you continue, “CW had something of a ‘head start’ in relation to the rest of you. He knew how to win debates inside those dark and suffocating halls, and he had mysterious friends he could call on who knew Marx and Lenin and Mao, chapter and verse” [165]. In what ways did the Weather Underground represent a form of left sectarianism in the 1970s comparable to other sects coming out of the Revolutionary Youth Movement (RYM) such as Klonsky and the others? What is missing from a Todd Gitlin-style of critique, an anti-ideology critique, which considers both of the dominant factions of SDS in 1969, Progressive Labor and RYM, to have somehow “imported” ideology into SDS? How does this distort something, however fraught and uncomfortable, about the “radicalization” of the New Left in the late 1960s and 1970s?

BA: I refer to Todd Gitlin, who was a friend of mine, as the self-appointed CEO of The Sixties Incorporated, the worst iteration of the mythologizing of that period. Gitlin is the person who sees all the “mistakes” with 20/20 hindsight, and can dissect every experience and illuminate each circumstance. To me, it is a fool’s errand. It also is an inauthentic search for a true history.

My sense of what happened is that, as I said a minute ago, we started off in the early mid-60s devoted to learning through action and to developing our ideology through action. We hoped to refine our principles through acting in the world. The Civil Rights and anti-war movements took us a long way. But then we reached the crisis beyond which it became difficult to know how to move forward.

We had done everything we knew to do, and still we couldn’t end the war. We couldn’t even stop other wars from starting. Our simplest and most straightforward goal was mysteriously beyond our ability to accomplish. That was the immediate source of the crisis and that in turn led us to wonder: How can we better understand what is going on?

At that point, we turned to study, trying to learn more. I spent a summer in a tutorial with Stanley Aronowitz to discover how Marx might help us figure out where we were. This was a complicated moment for me.

While it is true that there was for many at least a return to Marxism in the late 1960s, it is also true that we always had Socialists and Communists in the Civil Rights movement, the Black Freedom movement, in SNCC, and in SDS. Our position on that in the early mid-60s was pretty much: So what? The anti-communists like Michael Harrington were trying to tell us to be careful. In SDS we had an open conversation in which we decided that if the Communists party tried to join us we would subvert them. We’d force them to get over their conservative hang-ups. We were a little arrogant and a little crazy, but we were also serious. And our view was, in effect, why should we debase our movement by placing ideology-tests on it from the outset. We said let the people decide. And, certainly, we were not going to exclude people from the bottom of society on such grounds, since we knew that such people would prove indispensable in transforming society.

So, we began with the notion that experience is the best teacher for the Left, but in the end we came back to ideology. I think it was a necessary step. Ideology is both needed and dangerous. It is dangerous because it always has limits. It is needed because without it you are always floating along in a bubble of experience and you can’t understand how one thing links to another. We were fortunate to have people like CW who knew what they were talking about and were steeped in it. But it is also true that for a time we became quite dogmatic in our ideology. If I learned one thing in my long life, it’s that sectarianism can imprison one in a well-lit cell of one’s own creation. It definitely was a problem for us.

SL: I want to ask about Vietnam in relation to anti-imperialism in the present. I interviewed a former comrade of yours, Mark Rudd, on this show some years ago. At that time, Rudd, drawing upon arguments made earlier by Noam Chomsky, made the striking claim that in an important political sense the U.S. won the war in Vietnam. He drew from this the conclusion that the Weather Underground was somehow proved wrong. As he said,

Our group—which became Weatherman but which at the time of the split was known as Revolutionary Youth Movement I, adhering to what was called the Weatherman paper—thought that Che’s strategy was a prediction of the future, which was to “create two, three, many Vietnams.” We expected many more military defeats for U.S. imperialism in the later part of the 20th century. We did not understand there was only one Vietnam, which hardly mattered because the Vietnam War was not globally strategic…. [while it is true that] the United States was defeated militarily and forced to end its occupation of South Vietnam…, Vietnam never served as a model for any other revolution… [The American warmakers’] only goal was to defeat a revolution that could serve as a model for others. After the United States completely destroyed North and South Vietnam…, it could no longer serve as a model.[2]

In the late 60s and early 70s one slogan was “Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh, the NLF is gonna win!” Taking seriously Rudd (or, rather, Chomsky’s) argument that the U.S. accomplished its war aims in Vietnam, and given the collapse of the left internationally a slogan like that seems utterly untenable in the present. It seems dubious to claim that American imperialism is inevitably going to be defeated by the rising tide of revolution. Certainly, the Left today cannot say that with the kind of conviction it could in the 1960s.

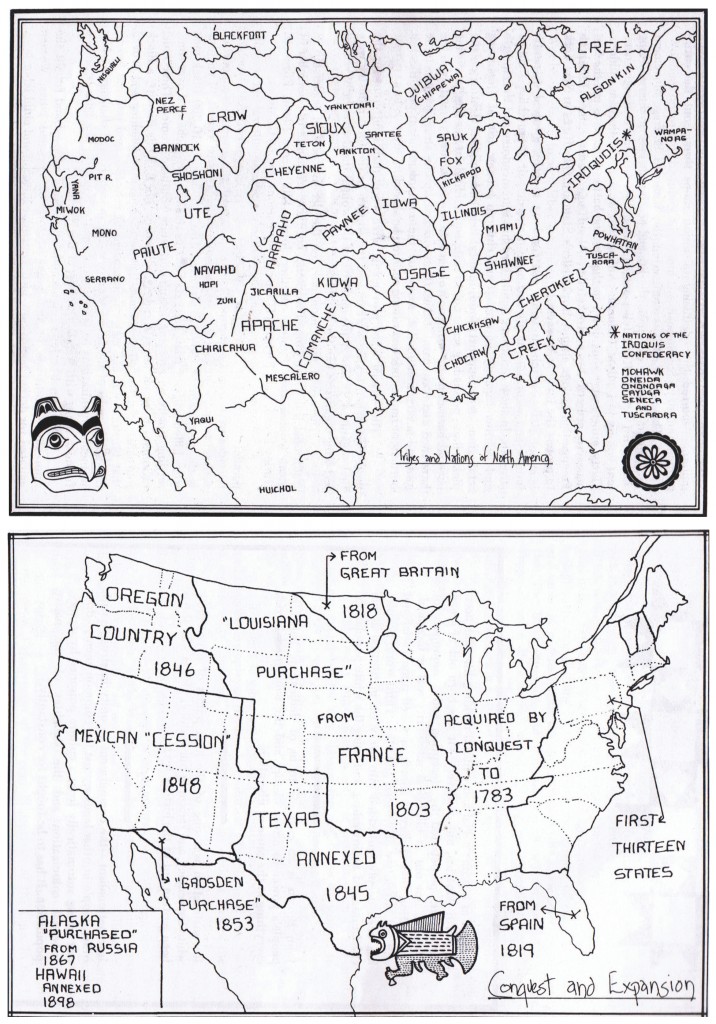

Tribes and Nations Conquer and Expand: This pair hand-drawn images illustrating the supersession and displacement of Native American peoples by an expansive capitalist settler colonialism appear on opposite pages of the Weather Underground’s 1974 “Political Statement,” Prairie Fire.

BA: I think you’re right. There are some very good reasons why that is true. We can see it in the wars the American imperialists are involved in now.

What we witnessed in Vietnam was a peasant revolution, an actual revolution. This is hard to imagine today: A bottom-up mass revolution, where social relations are actually made to change. That revolution was not going to be defeated by military invasion, however massive.

In the mid-1960s, we recognized that the US was picking up the threads of the French adventure. The reason we chanted “Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh” is because we were supporting an actual revolutionary movement. That’s not the case in Iraq, or in Libya or in Syria. So we are in a different moment. That this would be so was impossible to see at the time, without benefit of hindsight.

If you think back to the early 20th century, all progressive people were energized and taken down a very long road by the Russian Revolution. The idea then was that the revolutionary agent to transform every society and every social relationship was the industrial working class. That’s what the Communists latched on to, for quite sensible reasons. By the time we were coming of age, the Vietnam War and, more generally, the anti-colonial struggles that burst forth at the end of World War II led us to believe, just as fervently as the communists had once believed in the proletariat, that the engine of revolution, the engine of total transformation of the world was the Third World Liberation movements fighting against Empire. We saw these movements as cutting off the tentacles of empire. When we were writing Prairie Fire we could see it quite vividly: The empire was in terminal collapse, in Vietnam, Cuba, Chile, Angola, Mozambique, South Africa, and Mexico together with the Southwestern United States and, eventually, in the Blackbelt of the United States. Now that all seems kind of fantastical right now, but that was the project we instinctively at first, and then ideologically, attached ourselves to. The Black Freedom movement to us was an anti-imperialist uprising inside the borders of the US. The greatness of Malcolm X, part of the reason he stands out as such an extraordinary thinker, is because he recognized that the Black Liberation movement was not simply a civil rights movement, a movement for the rights of a minority inside the United States, but it was a world majority movement. Malcolm saw the Civil Rights movement as the Third World project expressing itself inside the borders of the United States. This, to us at the time, was an energizing and exciting and wonderful thing. It seems untenable to think that way now and for a lot of the same reasons why the model of the Russian Revolution went up in flames. The model of the Third World Revolution being the “engine of History” has also reached a kind of end point. It was subverted from within by corruption, repression, and deceit. Certainly, nobody can quite imagine “Two, three, many Vietnams!” as a strategy today.

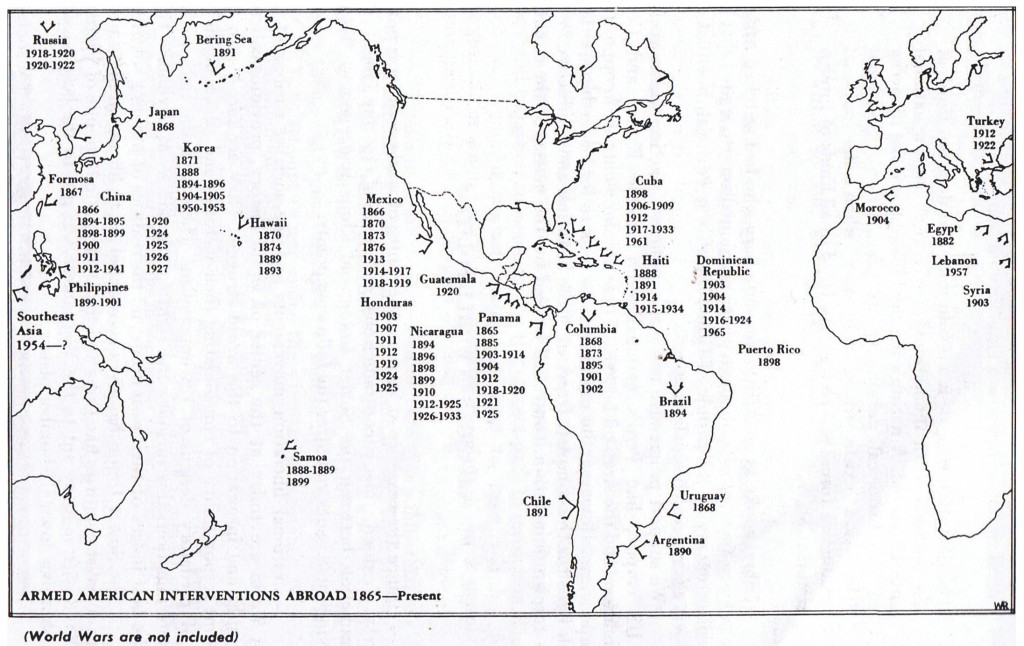

Another cartographic image from Prairie Fire illustrating the Weather Underground’s understanding of the growth and extent of American imperialism. This image shows how after having conquered the continent (see image above) the United States after 1865 proceeded to project its power through armed interventions abroad. Of particular concern is the item on the map listed simply as “Southeast Asia, 1954-?”

SL: In Fugitive Days you mention at a couple of points your encounters and affinities with anarchists. Nowadays, Marxism has very largely vanished as an ideology on the left, while anarchism seems to carry on. For instance, it was in the forefront of both the anti-globalization movement of a dozen-plus years ago as well as, of course, the more recent Occupy movement. As you note in Public Enemy, you and your wife and comrade of many years, Bernardine Dohrn, found yourselves at the recent protests against NATO and the G-8 Summit in Chicago “drifting over to the Black Bloc” because, as you say, “you liked their militancy.” You note their slogan at that march was the “most unifying” (though perhaps less than clarifying politically): “Shit’s Fucked Up.” Do you see the Weather Underground as a historical precursor to contemporary militant anarchism? If we allow that the legacy of, say, the Weather Underground is somehow visible in black bloc anarchism, what is distinctive about both that this comparison might lose sight of? Certainly one can’t imagine the Weather Underground could ever raise a slogan that politically vague.

BA: I like its vagueness in part because of its harmony and inclusiveness. Who can’t join in under the slogan “Shit’s Fucked Up”? Whether you can’t pay your student loans, your healthcare is a mess, your cousin got deployed in an imperial war, your uncle’s doing life in Statesville, or you can’t get a job, shit is definitely fucked up!

More seriously, I can’t judge whether the Weather Underground was a precursor of today’s anarchists, but I will say we thought of ourselves as influenced by Marx, but as also anarchistic in both style and to some extent in substance. We traced our thinking not just to Marx but to Proudhon, Bakunin and others. We learned from the Wobblies. Certainly, we thought of ourselves as homegrown as apple or as cherry pie, as H. Rap Brown said. We didn’t think of ourselves as importing anything.

Of course, the question might be: Is Marx relevant? Of course he is. You cannot understand the crises buffeting imperialism without reading Marx. So, Marx should be read. I participated in Occupy, Actually I participated in a dozen different cities and at Occupy I found myself enormously drawn to the Marxists, just as I was drawn to the Black Bloc.

Occupy had a different temperament and a different culture everywhere I went. So, in Chicago, it was just a street corner. In Detroit, it was almost like a homeless center. In Boston, it was a giant expanded public library just as you would expect. At these different Occupy sites I was asked again and again to do a workshop on theCommunist Manifesto. That strikes me as not odd at all. Here are these anarchists. They are action freaks doing their thing. But there is not a single action in the history of the world in the last hundred years of a progressive nature in which people didn’t reach for the Communist Manifesto. These anarchists want to understand what’s going on, and there’s no place better to study the Communist Manifesto than in an occupation or a sit-in or a demonstration.

SL: In reply to repeated calls for you to disavow your past, you have said that you would be willing to answer any and all questions, to account even apologize for any mistakes you may have made, if only others, prosecutors of the Vietnam War, would do the same. You claim that such a Truth and Reconciliation Committee on Vietnam would in some sense allow for history to be exorcised of certain specters haunting the present. But in what sense is such a reckoning possible? And haven’t we had hundreds, even thousands of books and films about the Sixties and the Vietnam War, never mind how many academic discussions? Robert McNamara even (sort of) apologized! So, I’m interested what exactly does our existing public sphere discussion fail to accomplish as regards historical “truth and reconciliation”?

BA: It’s not simply a matter of having a lot of opinions and treatises and perspectives on the table—a truth and reconciliation process requires a critical mass of people committing themselves to a dialogue in which they face one another without masks, listening with the possibility of being changed and speaking with the possibility of being heard. This can happen sometimes under a compelling moral leadership, sometimes in concert with organized and recognized authority, often in the noise of the crisis or the blast of the whirlwind. It happens when enough folks find it necessary to do something in the hope of becoming unstuck—not true here, not now, and not yet. But someday, possibly. History of course is in continual creation and recreation, not just what happened, but what is said to have happened and what all the happenings mean. There are no neat boundaries here, but a flow and a contested space. We are all actors and narrators and meaning-makers, and as the crisis deepens here we may see an urgency to go on that quest together. Truth and reconciliation—not an end-point, but an exciting and immense journey.

SL: Again—on this question of coming to terms with the past—it seems to me that when you were first politicized in the mid-1960s, you were then wading into a history scarred by innumerable defeats and betrayals. There was much that was “irreconcilable” in the postwar world. History was already pretty “dishonest” then, it seems to me. And I don’t just mean that the right conventionally understood and controlled the narrative, but that the history of the left was perhaps the deepest problem your generation faced. Does not the present inherit that problematic history, too? A history that the New Left can be said to have only partially come to terms with?

BA: Yes, surely. So there’s a lot of work to do.

SL: Much of Public Enemy is taken up with the 2008 Presidential campaign and the way in which you were dragged into that as a supposed “domestic terrorist” with whom Barack Obama had at one time “palled around.” You describe the outcome of that election, Obama’s victory as marking something of the end of an epoch. Presumably you meant by that that the epoch that began with the civil rights movement had, in some sense, come to an end, even if racism persists. However, unlike the time in which you were first politicized, in this new epoch, for the rising generation, there isn’t really an “Old Left” to react against: The New Left is the only “old left” this generation knows and that past has itself become quite opaque, as I think your comments here about the Sixties industry suggest. What prospects do you see for the overcoming of the legacy of the New Left in the way that is needed to constitute a left adequate to these new, and in many ways unprecedented times? While, as you point out, there have in the past always been lulls in leftist activity—how do we view the exhaustion of both the Old and New Left with nothing yet emerging capable of taking their place? Is this unprecedented in your view?

BA: When I say that Obama’s victory represents a shift, what I mean is that his election is a blow against white supremacy, not a fatal blow to be sure, but a blow nonetheless. That said, a lot of people make a lot of mistaken assumptions about Obama. But what this liberal disappointment with Obama misunderstands is that he always was (and always said he was) a moderate, middle-of-the-road, pragmatic politician. The Right said, “No he’s a secret-Muslim-closet-socialist palling around with terrorists.” The Left said in effect, “He’s winking at me!” But he wasn’t winking.

I think we spend too much time worrying about the Presidency and Congress, sites of power we have little or no access to. What we ought to be doing is spending our time focusing on the sites of power we have ready and absolute access to: The street, the workplace, the school, the community, the classroom, the neighborhood. That’s where we ought to go. As for what comes next I have no idea. There are always mountain times and valley times in any social movement. Incidentally, nobody living at the end of feudalism could see that feudalism was ending. Everybody saw its decline, but nobody could predict the institutions that would take the place of feudalism. Nobody could really map out capitalism. So, we ought to be somewhat humble about what’s coming. Is a new world coming? Absolutely, without a doubt it is racing towards us. Is imperialism in decline? Fatal decline. The terrifying thing about U.S. imperialism being in decline is that I don’t have any confidence that Chinese imperialism will improve anything. Still, in our moment now the U.S. remains the dominant political, cultural, and economic power. Its military grip is unprecedented and unrivaled. Thus, we are in a very difficult, very treacherous situation. Our job is as always to open our eyes to reality. Ideology can help with that but it can also blind us. That’s why we have to be careful as we move along. We need to open our eyes to the reality around us and make concrete analyses of concrete conditions. We need to act on whatever the known demands of us. In my view, we should be fighting for more peace, more global justice, and more democracy at every level. We should fight for racial justice and an end to mass incarceration. These are movements that can link up and can be built into mass movements with transformative power. I don’t know exactly what direction that will take. I could not have predicted Occupy the moment before it happened, though the day after it happened it seemed utterly inevitable. As for Occupy being a failure. In what ways was it a failure? Do you really think a tent city can overthrow the state? I don’t think so. It did succeed in changing the conversation in dramatic and unprecedented ways. Occupy gives me confidence that new things are on the horizon. At the same time, we can be sure that the change that is coming isn’t necessarily for the better. We could have slave camps, nuclear war, and a lot worse. That’s why it is up to us to get up, open our eyes, and get busy.|P

Transcribed by Miguel Angel Rodriguez

[1]. William Ayers, Fugitive Days: A Memoir of an Antiwar Activist (Boston: Beacon Press, 2009), 309-10.

[2]. Spencer A. Leonard and Atiya Khan, “You Don’t Need a Marxist to Know Which Way the Wind Blows: An Interview with Mark Rudd” Platypus Review 24 (June 2010).