Marxism and feminism

Roxanne Baker, Judith Shapiro, and Sarah McDonald

Platypus Review 106 | May 2018

On February 17, 2018 the Platypus Affiliated Society hosted a discussion at its Fourth Annual European Conference at Goldsmith’s University on the subject of “Marxism and Feminism.” The event’s speakers were Roxanne Baker of the International Bolshevik Tendency; Judith Shapiro, Undergraduate Tutor at the London School of Economics; and Sarah McDonald of the Communist Party of Great Britain. The event was moderated by Erin Hagood of Platypus. What follows is an edited transcript of the translated discussion, an audio recording of which is available online at: archive.org/details/MarxismAndFeminism.

Opening remarks:

Roxanne Baker: There has always been a separation between feminism and Marxism and the fault lines between them do not really change as much as each new generation of activists tends to assume. The form differs, but the same fundamental patterns reassert themselves, because we are still operating within class society, more specifically within capitalist society. So, one hundred years after the Representation of the People Act, it is worth examining the courageous, groundbreaking feminism of Emily Pankhurst, even if it was separatist and elitist; and it is worth comparing that to the activity of her Communist daughter Sylvia, who focused more on working class women in the East End. The distance between these two counterposed approaches has varied during the last century, but the fundamental ideological divergence has remained.

The fight for women’s emancipation is inextricably tied up with the fight for human emancipation, that is, with the struggle to end class society and all the forms of social oppression that it generates. Of course, concrete struggles to address particular aspects of women’s oppression must be taken up today, but the victories won can only be partial and transitory as long as capital rules. The material basis for completely uprooting the cause of women’s suffering requires a revolutionary social transformation such as only can be accomplished by a mass revolutionary party based on a Marxist program and composed of revolutionary women and men, together in the same organization, committed to fight for all the exploited and oppressed.

It is important to clarify the real differences between Marxists and feminists, because many feminists believe that socialists regard women’s rights as something that we can wait until after the revolution to solve. But the revolutionary Left has always considered the fight for women’s freedom as fundamental to the struggle for a socialist future. The struggle against the special oppression of women and other oppressed groups—racial ethnic, sexual minorities—will be crucial to assembling the social forces necessary to challenge the control of what is, after all, a powerfully entrenched ruling class. Assembling such social forces is inconceivable without the active participation of half the population, obviously. But the converse is also true: To try to end women’s oppression without a class perspective, without a perspective on overturning capitalist tyranny, is not only counterproductive, but in the end always results in the betrayal of those who most need to be unshackled, the poorest and most oppressed women around the world. Feminism, even in its socialist–feminist manifestation, tends to prioritize female emancipation over all other questions, or at least to approach the problem of class divisions alongside gender divisions. This leads feminists to emphasize the autonomy of women’s organizations.

Our organization identifies with the tradition of the Russian Revolution and advocates for the creation, as a transitional organizational form, of a mass communist women’s movement focused on the revolutionary mobilization of women. This can only be done by actively addressing women’s particular concerns. To be effective, such organizations must exercise considerable autonomy in the sense of being able to decide how to allocate their forces and what priorities to pursue at a particular moment. But such autonomy exists within a division of labor and in coordination through a revolutionary party with other elements of a revolutionary movement. That is partly how they derive their power and education as well. So, Marxists struggle for women’s rights now, not just in a future communist society. The International Bolshevik Tendency (IBT) has a record of participation in united fronts around issues such as the defense of abortion rights, reproductive rights, childcare, healthcare, and housing. These disproportionately affect women, but are also of crucial interest to the whole working class.

The #MeToo campaign began with accusations against Hollywood heavyweight Harvey Weinstein, who seems pretty clearly to have been a serial abuser. This is a good example of where Marxists and feminists both overlap and diverge. The unwanted sexual advances, comments, moral condemnation, etc., that all women experience have a cumulative effect. They comprise a large component of our oppression under capitalism. The #MeToo campaign on social media has exposed how widespread this problem is, how normalized and culturally ingrained. Obviously, this needs to change. Where Marxists diverge is with respect to how this can be achieved. The deep structure of the social relations that condition all aspects of life in this society, including relations between men and women, cannot be fixed on an individual level. Nor can they be fixed by pitting women against men. Sexual harassment, sexual assault, and the inequalities between individual men and women reflect the economic and social oppression generated by a profound inequality of power, status, and economic resources. Women are at greater risk when other inequalities are present. While individual behavior can be modified and social pressure can be brought to bear (and has been brought to bear) to reduce the incidents of these abuses, the root of the problem cannot be addressed simply by reeducating men, but only through undoing the power disparities that come with capitalism.

The #MeToo campaign, which aims to empower women, focuses on the sexual indignities and criminal assaults that we have all suffered. But this campaign can easily play into the hands of those who want to deny our sexual agency or present sexual activity itself as a danger to women. Marxists and most feminists want to fight for a society where everyone is free to express their own sexuality, free of any sort of legal or economic compulsion, on a fully informed, consensual basis. And it is necessary to distinguish sufficiently across the vast spectrum of incidents, ranging from rape to unwanted comments on the street. Neither is acceptable, but these are actions of very different magnitudes, which deserve very different responses to, and consequences for, the perpetrator. The bourgeois justice system is notoriously bad at dealing with rape, but to respond to this by asserting that all accusations should be believed and made public, fosters a climate of trial-by-media, does not guarantee justice for the victims, and potentially destroys the lives and careers of the innocent. Disregarding the principles of due process and the presumption of innocence creates dangerous precedents for working women and men, particularly for those who dare to challenge the ruling class. For example, employers otherwise uninterested in the well-being of their female employees might be happy to level unsubstantiated charges against trade unions militants as a pretext for firing them. Certainly, such accusations have historically been used to target leftists and others considered dangerous or inconvenient. In the U.S., lynchings of black men were commonly justified by claims that they had sexually violated white women. Men who assault or rape women must, of course, suffer severe consequences, but the limited safeguards we have won to protect the innocent against arbitrary and capricious persecution by the state or by employers must be jealously protected.

It is noteworthy that the mainstream media only began to take serious notice of sexual harassment in the workplace when it involved high-profile Hollywood celebrities. The constant, unrelenting sexual harassment of low-paid women in the service industry, for example, is of no great interest. But because women are at greater risk of sexual harassment and assault when other inequalities are present, we have to link them to the social basis. Successful bourgeois politicians such as Hillary Clinton, Theresa May, and Angela Merkel have shown how ultimately irrelevant gender is. Under their watch, nothing much changes for ordinary working women, unless it gets worse! They talk about women’s equality, but their actions serve and protect the status quo. The attempt to build female unity across class lines, as feminists tend to do, amounts to subordinating the interests of poor, black, and working-class women to those of the rich, ruling class women, who derive substantial benefits from the existing social order, regardless of what they may endure as women. The Marxist strategy of uniting all those exploited and oppressed by capitalism is the only way to lay the basis for a world free of social inequality and material want, and thus to realize the possibility that each woman or man pursue their own path and enjoy fulfilling personal lives. The pathology of sexual violence is at bottom a social problem that derives from a society that celebrates and rewards selfishness, possessiveness, and the ability to wield power over others. The only way that the full human potential for love (and for all other aspects of our lives) can be realized is through the creation of a rationally planned socialist economy that can provide secure access to the essentials of existence for all. Once the material basis for social egalitarianism is achieved, the daily brutalities experienced by women at every social level, but particularly by those on the lower rungs of the social ladder, will gradually become a thing of the past. Until then, the best we can do is to struggle against the inequities both great and small imposed by capitalism while actively seeking to construct a viable revolutionary movement capable of ending once and for all the horrors of class society.

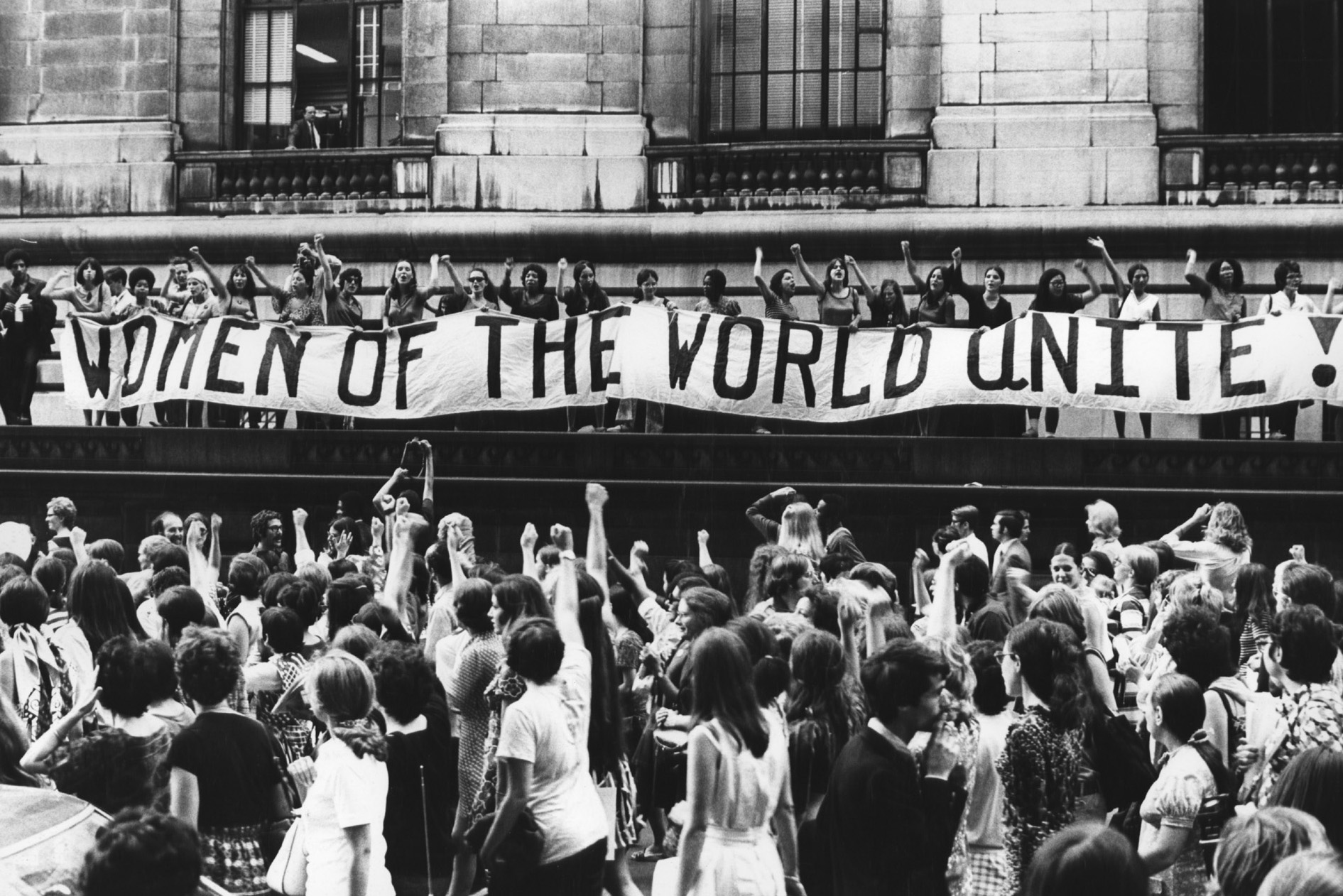

Women's Strike for Peace and Equality New York City August 26, 1970

Judith Shapiro: I was raised in the same tradition as the first speaker, who sees feminism and Marxism as distinct. And I did not get that from the Spartacist League (SL). I joined the SL because it accorded with my interest in women’s liberation and class struggle. So I share the view that it will take socialist emancipation to have women’s emancipation. (I do not like the word “emancipation,” notice the root there; the word “liberation” is better, in my view.) That said, it is unbelievable how much has been accomplished within the framework of bourgeois movements. Those of you who are not my age cannot imagine. I grew up in the 1950s and because of my parents—like a lot of New Leftists in the United States, I was a red-diaper baby—I knew exactly how bad it was, and not just for women. Everything was repressed.

Here are some things fascinate me: Why did it take years to invent a suitcase on wheels? Because it was not done to have suitcases on wheels. About rucksacks: I was the first person to wear one. I used to embarrass my students at Goldsmiths until they discovered they were trendy. I just did not want to carry my books the old way anymore! We have seen something similar with hemlines. These changes occur partly through the process of education and through the world getting richer. But it also partly happened due to politics. One of the things I am proudest of is that I was a molecular part of the founding of the women’s liberation movement in the United States. Someone in Belize is doing a PhD on the history of the American women’s movement. On the map she has developed there, I am in the upper left-hand corner, near Seattle.

One reason I do not like the label feminist is its association with a creepy kind of radicalism: this insane acting-out. Students come to me interested in the Wages for Housework movement. When that does not get enough attention, they form the English Collective of Prostitutes to act out. I would not try to reason with these protestors the way I would with you, because reasoning is not what they are doing. What they are doing is expressing themselves. It is expressive politics. There has been too much of that. It does not work terribly well.

We built the women’s liberation movement, and it made big changes: The very first abortion referendum was in the state of Washington. We had buttons with a coat hanger on them. We had a very active campaign and, in some ways, I regret that Roe v. Wade overtook it. Because if abortion rights had to be fought for everywhere, as opposed to relying on this Supreme Court ruling, the movements to defend abortion rights would be stronger. That does not mean I wish that the Court had ruled the other way. I just wish that it had not been so “from above.” At any rate, there was a great deal of progress made within the confines of bourgeois society. Women have abortion rights and do not have to panic about the possibility of getting pregnant, like my generation did when there was no legal abortion. Is that enough?—No.

We can have an intelligent conversation of what #MeToo represents and how we should relate to it. There’s a wonderful Saturday Night Live sketch you can catch on YouTube: Couples start to talk about #MeToo and, as soon as somebody does, they go “Oooh! Don’t do it, don’t do it!”[1] There is no way you can put a foot forward without saying something. Either you do not care about the rape victims or you do not care about due process. What we need is debate where we do not simply attack each other. We should turn the word “safe space” around to mean freedom to say what you want to say without being accused of reprehensible motives.

Intelligent political culture and discussion are things I feel strongly about, not least because I have spent most of my life since I left the SL worrying and thinking about the Soviet Union, and then Russia, which lacks this political culture. It is also possible sit in a room together where people just talk past each other. So I would encourage the audience not just to say what they came to say, but to address each other. Even if you are not rude to other people, but still ignore them, the discussion does not move forward.

My instinct is that #MeToo is getting to be a distraction because it is driving out all the other questions. But maybe I’m not right! I absolutely agree about the cumulative effect of harassment. We are not saying that one stray hand, one wolf whistle is unbearably terrible; the trouble is when you have to put up with that sort of thing every day. But I do not observe that as much anymore. It is not like it was even twenty years ago. One of the reasons people have come forward is that we all know what is wrong. So, then, we have to address other questions, which have to do with, how far are you responsible for the ethos of a previous generation? Which we have come up against, right? It is an exciting time, because there seems to be a new wave. I do not know what created it. Is there something that is happening now that women have achieved—in the advanced capitalist countries, certainly—all they can achieve legally, and now they want more? It deserves the title Third Wave.

It is an exciting and wonderful time. I do not love the word “feminist,” because it does not sit well with men. But I do not have an alternative. I read forty definitions last week, and there are about twenty I can agree with, all of which distill down to advocating for women’s equality. What I dislike is the idea that the first slice you take is women, which comes down to saying, “I would rather have a racist female than a male who believes in all the things I believe in—social justice, equality of races, and so on.” So, I have no other word than “feminism.” I think we need to take it over, give it our own meaning, and drive out the others. As for its relationship to Marxism—if Marxism is universal, then we would not have feminists talking to Marxists, because you would not have to distinguish between the two.

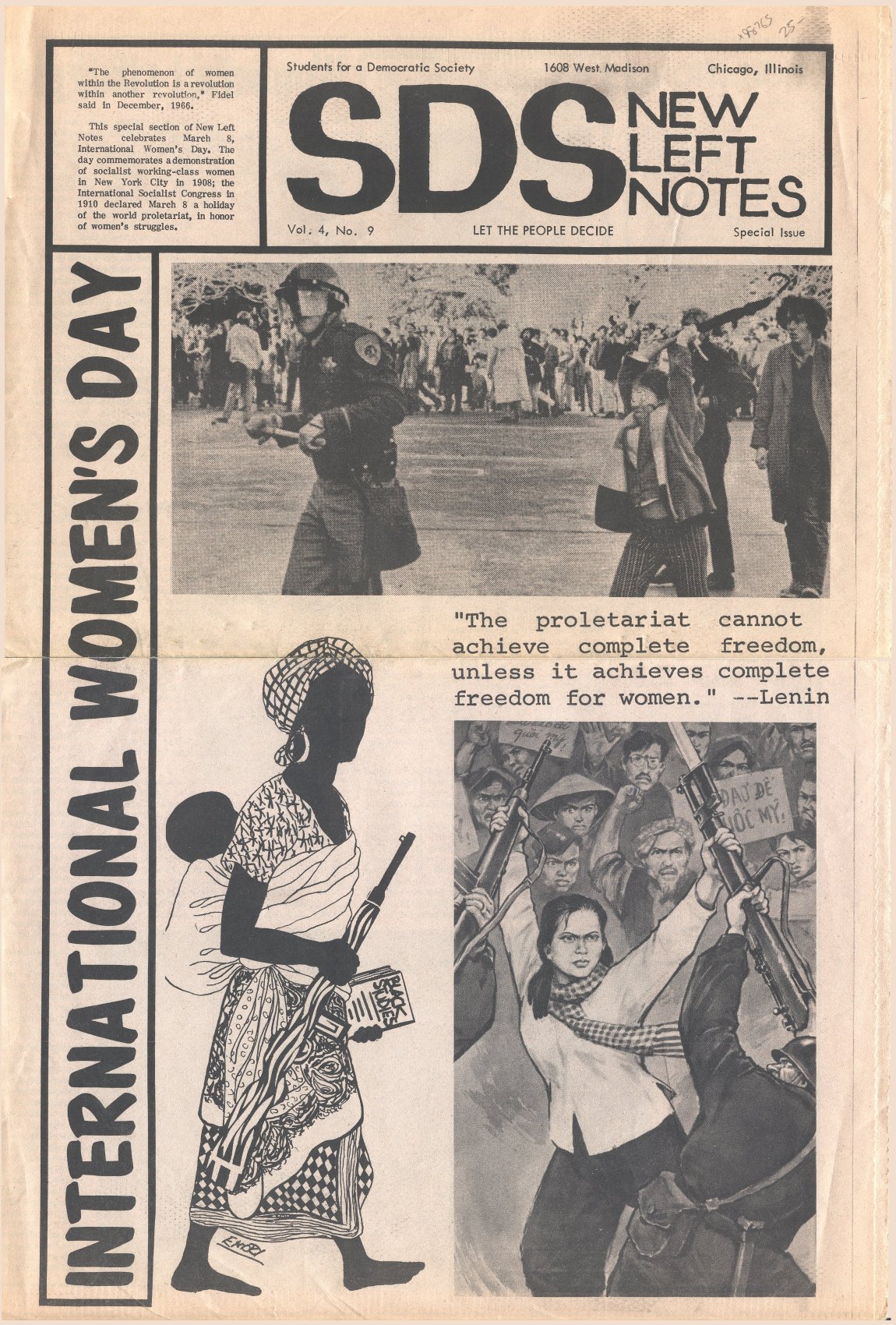

The cover of 1969 International Women's Day special number of "New Left Notes" (Volume 4, Number 9 - March 8, 1969)

Sarah McDonald: So, what is feminism? As a Marxist, I define myself in terms of class politics first. I agree with much of what Roxanne said. In fact, I expect there is not going to be much disagreement, except perhaps about some of the #MeToo stuff.

Women’s liberation, liberation of half the population, is not just something that is desirable. It is absolutely necessary. For me, that is part of the class struggle. It is part of the—and I do like the word emancipation—the emancipation of the whole of humanity. But, as I say, I view that from a class perspective first. Why? Because all of the other issues—whether it is gay liberation, women’s liberation, etc.—all can be resolved through the emancipation of the whole of humanity by the working class as an agent for overthrowing capitalist society. It is the biggest stakeholder in that, whereas the women’s movement cannot emancipate the whole of society. So, it goes that way around for me. This is not to say that you defer addressing women’s liberation until the other issues have been resolved. Rather, addressing these questions is fundamental to our movement. That said, there are massive differences between the UK and America, not to mention different countries in other parts of the world.

They say women’s work is never done, and it is true. Most of us work, whether in professional jobs working very long hours or in part-time jobs, often working multiple jobs. Many women have a second burden of doing housework, rearing children, doing most of the caring in the relationship, taking care of the elderly, etc. A lot of that burden falls upon women in western advanced capitalist societies, even more so in other societies. Judith spoke about the gains that have been made. It is important not to skip over that. And it is not just that I have got a rucksack that does not give me a bad back when I am carrying stuff around. It is also education, abortion rights, legal equality (whether that manifests itself financially or not), representation, even down to taking out a mortgage, or being able to order a full pint at the pub, which even in the 1970s women could not do. And there is plenty more that people can come up with.

Regarding hemlines, if you look at the way that we are told to look, the way we are told to dress, how we are criticized for dressing a certain way, the amount of makeup and time we are supposed to spend preening, pulling the hair out of your face, the amount of time that you spend on dieting and working out—all of these things conduce to a certain conformity, whether within white Western culture, Asian culture, African culture, or something else. So, yes, there have been massive gains, but it is not true that women are no longer criticized for their hemline.

Roxanne mentioned the centenary of the Direct Representation of the People Act in 1918. That is something worth having a conversation about, because the mainstream has really coopted it, turning it round into something it was not. I got annoyed with the BBC Radio Four day program as I was getting ready for work the other week, because they did not mention working class men getting the vote at all. There was a tiny point, “It was women of property over thirty.” So married, middle-class women over thirty got the vote—that was mentioned as an aside. And this was portrayed as something given by the establishment as part of Britain’s upward and onward trajectory towards progress, tolerance, democracy, and respect, and all that kind of thing. No mention of the Russian Revolution. No mention of the First World War. Why did working class men get the vote? Why did all working class men, universal male suffrage, happen at that point? It was a preventative measure. Why were not all women given the vote? Because the Labour Party would have gotten into power. Middle class women of property were less likely to vote Labour.

Now we have Theresa May, Nicola Sturgeon, and Ruth Davidson talking about safety for women in politics: Women ought not to receive abusive tweets and require a safe space. This is about creating the culture of victimhood. The suffragettes were brave women. They created social disturbances, committed acts of violence, and risked, even lost, their lives for the vote. Few on the Left so much as mention Sylvia Pankhurst, though she is the obvious heroine of the period: learned jiu jitsu, learned to fight off the police, organized the East End of London, established relationships with Moscow, and the rest. Somebody that fundamental is just written out of the story.

And there is another relevant date coming up: The eighth of March is Women’s Day, International Working Women’s Day. It will be all about Hillary Clinton and female CEOs. Yet, the holiday comes from a New York Machinists strike. And what happened on the International Women’s Day March in 1917? The Russian Revolution. As for Alexandra Kollontai, Clara Zetkin, and the rest, they are certainly not taught on Women’s Day. The establishment has made it their own.

As for #MeToo, there are massive differences between genuine abuse (rape, sexual assault, etc.) and a bad date, or someone saying the wrong thing, or simply trying it on a little bit. It demeans sexual assault to similarly equate these things. Then there is the cultivation of the culture of victimhood I spoke of before. The whole notion of safe spaces tends to make oneself a victim. Rather than standing up and fighting, you wrap yourself up in cotton wool.

What is fundamental is the question of power relations. If you are working in Hollywood and your producer says you have to sleep with him in order to get your next job, or to ever work again, that puts you in a tough position. If you can tell somebody fuck off, that is different.

I do not believe in wages for housework. In Vienna a few years ago I went to Karl Marx-Hof. They had collectivized the laundry, food preparation, housework, and childcare. It was all very smart, but it was also just collectivized domestic drudgery. It was all women doing these boring, menial tasks. Yes, it was made more bearable by being done collectively. But it did not emancipate.

I have often heard on the Left and in the feminist movement that women are more cooperative or even somehow inherently more progressive. You know Margaret Thatcher was progressive, because she was a woman! No, that is ridiculous. Women jurors, notoriously, in trials of rape cases are more likely to return a verdict against a woman victim, to say “she was drunk” or “she was wearing a short skirt.” Women do not have natural solidarity with other women. Token representation of women on corporate boards does not benefit women. So, yes, we should take advantage of opportunities to develop women. Especially on the Left we need to develop the women cadre that we have, recognizing the additional pressure that they might have in terms of work, childcare, and the rest. But there is no point in making a special effort to promote women. The question is, How do you create a culture where women are encouraged to speak, to read, to study, to build confidence, and the rest?

Responses:

RB: It sounded like what you were saying, Judith, was that the Marxist Left risks underestimating the progress already made by the women’s liberation movement. That was not my intention. I can appreciate that you have lived through great changes and you can really feel the difference. We certainly should not underestimate it. That is why it is so important to fight for reforms that make a difference to our lives now. But we best preserve the gains of the past by understanding that we have to change the framework.

I am a teacher at a fairly liberal school in the public sector. And even there, it is remarkable the conversations that I have with both students and teachers. The attitudes can be astounding. We still have conversations about skirt lengths, young girls wearing jewelry, and whatever. It can get pretty 1950s. So things have changed, but they have not in some ways as well.

I would be interested to hear what you think about the publication “Women and Revolution,” Judith. This was a useful educational tool for me that the SL produced. Some of the work they did was really important. Excellent work was done by Marxist revolutionaries intersecting the feminist Left, recruiting feminists, and trying to bridge the gap. They could do that because they had the most coherent framework, as opposed to the non-Marxist nonsense about wages for housework and stuff like that, the radical acting-out stuff, which still exists in various forms. So, yes, we have to move things forward within the confines of bourgeois society. Essentially, I think we agree but your emphasis is different there.

About #MeToo, I am a teacher surrounded by a lot of women. But when I talk to friends who work in corporate settings, the blatant sexism, harassment, even assaults that they face can be just sickening. If you ask the question, Why is the MeToo campaign happening? Partly it is to distract from the chaos of American society in particular and from the unraveling of the fabric of capitalist society in general, from the conditions of the working class worsening everyday in such a serious way. #MeToo gives people something to focus on.

I just want to end on one thing, which is Hillary Clinton. It might be a bit unfair to say this because Laurie Penny is not here. I would be interested to get her reply, perhaps in writing afterward. She very clearly supported Hillary Clinton in the presidential election and, for me, that is the logical conclusion of her socialist–feminist politics. It really came down to the fact that Hillary Clinton is a woman. It is a question of feminism vs. socialism. It is easy to hate Trump, but we also need to ask what sort of world we would be living in right now if Hillary Clinton were president. The fact that she is a woman that talks a bit left on female issues makes her more dangerous. It distracts from her very dangerous politics.

JS: My students tell me that Goldman Sachs has at their entryway a giant mural dedicated to the forthcoming eighth of March. I want it back, though that is not the right attitude. If we are really serious about the role of the working class, this is because it has the ability to act collectively that others do not. It alone can bring about the emancipation of everyone. But there is a tension between the idea of democracy that most people in this room share and the view that the working class is going to do the dictating—the view held, for instance, by the Avakianites.

In my day, when we used to go to Left meetings across the country, a bunch of us got into a car. We would take turns driving and helping to keep the driver awake. And we invented a thing called drivers’ democracy. Drivers’ democracy was a deliberate spoof on proletarian democracy. Drivers’ democracy meant only the driver got to decide if we smoked or not, if we stopped to pee or not, and, crucially, where we stopped, which matters if you are female, as Simone de Beauvoir noted. They have not yet invented something that will make us equal in the woods.

The point is not a woman’s right to wear a rucksack. People did not have a right to look unseemly. That was the thing. We had forces in society that were much more oppressive. And it is not entirely healthy that those bounds got broken, but mostly it was.

We can talk about the history of International Women’s Day, but we should not try to take it back. It is our job to be the frontrunners, rather than the sole owners, of socialist values. And even though there is no near prospect of socialism, these ideals are what drive us forward. International Women’s Day should be for everybody, including men, and not confined to being proletarian. Just remind people where it came from, like many other good things.

SM: I am going to start with a ridiculous anecdote on skirt lengths, because it is always a good place to start. A friend of mine—a male friend, mind—worked in an all-girls school. They had kilts and they had a very specific length that the kilt needed to be. The distance between the sock and the kilt needed to be just so. So there came a point where teachers went around in the corridor to check the length of the distance between the sock and the bottom of the skirt. This carried on to the point where it became difficult for the staff. So all the girls were expected to carry a piece of cardboard the length of the distance between the skirt and the socks. It became a punishable offense not only not to have the right length between the skirt and the socks, but also to be found walking the corridors without your bit of cardboard!

Less so on the Left, but within the wider society Hillary Clinton would have been seen as progressive. After all, Hillary Clinton is a woman and she is not Trump. If you look at her record in the Middle East and much else besides, the idea that Hillary Clinton would have been some sort of paragon of virtue is ridiculous. Still, I know a lot of female friends, particularly female friends from North America, that have this opinion.

On the question of the eighth of March, for me it is about the idea that you are suggesting to people that you do not have to fight for anything, because we are on this trajectory towards a progressive, tolerant, and democratic society. It is the establishment’s cooptation of the women’s question that bothers me. International Women’s Day was part of a fight. It was part of a struggle about the emancipation of men, too, and trying to end the war—people’s husbands and sons were being slaughtered. It was not just for women. So it is not just about, “This is ours and we want it back.” It is about acknowledging history.

The idea that the women’s question is not a question for men is wrong. If we are going to liberate the whole of humanity, it is not just women that need to address women’s liberation. If we are going to change sexist attitudes, that involves educating men as well. More often than not, men are the perpetrators of sexual assault, but men are occasionally victims of sexual assault. Boys are often victims. These conversations cannot happen without men. Educating men in the movement is something that we need collectively.

Q & A

A few years ago, we published an essay in thePlatypus Review entitled “Gender and the New Man,” written by Bini Adamczak. The thesis is that the concept of the New Man had a universal male character; that, even if the goal is to emancipate all of humanity, women would have to become like men. Progress would take place through the masculinization of women. What do you think about this thesis? It is not uncommon within some non-Marxist, feminist tendencies.

SM: Do women behave, or are they expected to behave, more like men? Sometimes. People are a product of their environment in different conditions. In the workplace, certain behaviors may get you promoted, while others will not. Certain things are seen as being very male. When I am assertive, I am perceived as “aggressive.” But when a man’s assertive, he is perceived as exercising leadership. But, of course, it is not so binary. There is a lot of crossover and a lot of conditioning in the way that people are expected to behave in different circumstances as well. Boys in certain circumstances will be expected to be macho. In others, they may be expected to be involved in theater or music. It depends on the cultural environment.

RB: I hear this discussion quite a lot in non-Marxist circles. I work with quite a lot of feminists. There is a disproportionate number in the English Department at my school. I have a colleague that people have called brash and aggressive. She explained to me that she quite consciously changes her behavior to be more like a man. To get something done, she will adopt a more masculine style. For example, if she wants to shut down a group of sexist boys she is teaching, she will adopt a certain style to gain herself some respect and then, as she builds a relationship, her style might soften a bit. Now, a hardcore feminist might say, “No, men need to be more like women. They need to use more tag questions, to be more open, to leave more space, to not interrupt, and so on.” This is also true. We can carry on having these conversations, but they refer to cultural problems. We need to change the conditions in which we live in order to see, for instance, what the potential for maximized communication would even be. So while these can be important conversations, they can get bogged down and prove distracting, as well.

Judith, when you talk about gains for women, isn’t this largely with respect to women in imperialist countries? The capitalist system in the imperialist countries has been quite willing to give some rights and concessions to women and gay people.

JS: I do not share this easy schema of oppressed and oppressor countries. Even though I do not consider myself a Marxist, I believe that your view is not Marxist, either. The notion that people mobilize so that the imperialists can grant them things is not plausible. The reality is that for various reasons, some women in Africa have long had more of the kinds of rights that we tend to speak of, yet that did not, and does not make them emancipated. I will give you a puzzle: In China, there is no doubt that up until 1978, women enjoyed greater equality than we have, with respect to certain measures: wage equality, access to jobs, etc. On the other hand, when the reforms started under Deng Xiaoping, there was an enormous increase in wealth in China, during which women became worse off, relative to men. I taught a class in August in Beijing and I put it to the students, which would you rather be: starving equally during the Great Leap Forward famine, or very unequal now, with better life chances? That is the level on which we need to look at things. “Imperialist nations are this, and the oppressed nations are that…” This does not correspond to the reality of what happens between countries, which is much more complex. Look at what happened to women in the Soviet Union, with its many ups and downs. It does not fit any simple schema of “imperialist country” vs. “oppressed country.”

One of the first things that you said, Roxanne, was that these mainstream political figures such as Theresa May, Sturgeon, and Merkel, have shown how irrelevant gender is. I thought that was quite an interesting comment, especially with what you were just saying about being masculine. Do you think gender could collapse? How do trans people fit in to this discussion?

RB: What I mean when I say that gender is irrelevant is that for these women, their political program is the ultimate thing that determines their actions. They happen to be women. Gender is not irrelevant in our lives, particularly as it becomes a part of our identity. If it is a part of our identity, that in itself can become political. So the oppression of trans women, for example, is a particular experience that is different to a cis-gendered woman. These things should be dealt with very explicitly. If we manage to change the social conditions, who knows how these things will all fit together. Maybe gender will break down. I do think that will happen, really. I think it is going to be mind-boggling, how we think about such things after we have broken out of the capitalist framework. But to go back to the original point, when I said it was irrelevant, I was really talking about how this is an example where class is most important.

SM: I disagree. Gender roles, I think, will break down, but I do not think that gender itself will break down. Most people identify with the gender they were assigned at birth. Not to be dismissive of people being trans, but I think it likely that this will continue to be true, in general. Women will probably still be the ones actually bearing children, as well. However, the roles of child rearing, along with how work is organized in society in general, will change.

JS: What is it going to be like? I do not know. I think we can look at the direction of change to get a clue. For example, women and men, on average, appear to have different spatial perception, as measured by IQ tests. What is fascinating, though, is that this gap is closing. So the question is not, “Is there a difference?” but, “How is it changing?” This also tells us something about whether it is nature or nurture.

The title of this panel is “Marxism and Feminism,” and the relationship between these two has often been thought of in terms of a supposed distinction between the “main” contradiction between workers and capitalists, as opposed to “secondary contradictions,” such as the women’s question, and migrants, and so on. This has led “post-Marxist” theoreticians, like Ernesto Laclau or Chantal Mouffe, to rail against “Marxist economism.” However, this supposed distinction between principal and secondary contradictions isnot Marxist, but rather a sign of the Stalinist, reformist decay of Marxism itself. Because really, revolutionary Marxism and women’s emancipation would need each other, the one towards the other, in at least three different ways. First of all, strategically, if you want to fight a successful class struggle, you need solidarity among male and female workers. (Also, female workers, along with black or migrant workers, are often more radical than white male workers.) Then, of course, you need to collectivize the economy in order to collectivize housework, provide childcare, and so on. And finally, in order to fight against sexist stereotypes, you will also need to expropriate the media industry which constantly produces, or at least contributes to reproducing, all these stereotypes. So, if you have a situation like the one in 1968, where the supposedly Communist Party in France (PCF) only fights for a 30% wage increase, then this is not at all Marxist. It is a question of a thoroughly reformist, degenerated Stalinist party that reifies the relationship between the workers and capitalists. I think all these so-called secondary questions are intrinsically linked to the struggle against capitalism. It is all one.

RB: More so than treating women’s liberation as “secondary,” in a very layered sense, Stalinism is the negation of women’s rights, often quite explicitly. The PCF’s role in 1968 was to contain the pre-revolutionary situation. Looking at the history of the Bolsheviks is quite useful in order to see how the question of women’s liberation fits into the struggle for human emancipation. Lenin in particular was very forward-thinking. He knew how necessary it was to create organizations that mobilized women, educated women, and drew women into the workforce. This was in the context of pre-1917 Russia, where women were much less educated. We do have different problems in Britain in 2018. But one of the problems we still have is that very few women are in the movement. How do we draw people in? Transitional organizations are one possibility. It is not about treating women’s liberation as a secondary question; rather, it is a strategic question, in the sense that we cannot have revolution without it. The line I am trying to draw is that what feminists do not understand is that at the bottom of it all is class; if we do not start with that perspective, we will always be going around in circles. Feminists usually acknowledge that it is a structural problem, but they are not willing to challenge that structure.

SM: I take slight issue with the notion that minorities and oppressed groups are more radicalized in general. I do not think that is historically true. It may be true in certain cases, at certain times. Just look at the Left. Look at this room, even: There are more women in it than most Left meetings would have, probably, but it is still nowhere near 50% women. With respect to race—again, look around the room. That is reflected in the Left much more widely. It is not necessarily true that, the more disenfranchised you are, the more radical you are.

JS: I agree. The question of oppressed groups and their degree of radicalism is an empirical question rather than a theoretical one. We have to look and see. Most types of oppression do cause people to act in response, but the kind of response can be, for instance, internalizing the oppression as norms.

What does Marxism have to offer to women,today? What is the problem that Marxism has to address? Is it just about labor and wages, or is it something more?

RB: Well, I still think Marxism offers the only way out. If we want to change the world, we need a coherent method to do that. Specifically, I think we need to build a revolutionary party on a Leninist model. That alone will not do it, but it is the necessary starting point. Exactly how such a party would organize itself… We do not have a mass revolutionary workers’ party in this country. We do not have one that has a coherent Marxist program, anywhere, at the moment. But for me, that does not mean that the necessary starting point has changed.

Judith, you have suggested that we are putting too much emphasis on Marxism, and are failing to recognize the gains that have already happened. But it is not just about that. You talked about making feminism and Marxism universal, rather than clashing. But they do clash. They want something very different. We should recognize that feminism can play a reactionary role.

SM: I generally agree with what you have said. But if we ask, “What does Marxism offer women…” Well, what does Marxism offer men?—It offers you a Saturday afternoon at Goldsmiths! It offers you paper sales, you know? What does it offer any of us today? Education. And hopefully, this is a part of a process of how we get to where we are going. And it offers emancipation for all of humanity.

JS: On this question of what Marxism has to offer, I do not think it can be answered in the abstract. It is one of the reasons I do not see myself as a Marxist. I think some of the questions that have been raised—that are very real in people’s lives—are the first thing to address. Wanting to engage in those does not make you a reformist.

I’m a comrade of Roxanne’s, from the IBT. I am a Marxist, which means I am not a feminist. I often get shocked reactions to that. A lot of Marxists call themselves Marxist-feminists; it is like they do not want to offend anyone. But I think this ideological difference is very important, as Roxanne’s explained.

The SL that Judith supported in the 1970s is not the SL we may know today. It was a revolutionary Marxist organization then; it is one that the IBT claims as part of our heritage. The SL was taking notice of the women’s liberation movement in a way that a lot of the Left was not doing. But they were unambiguously clear that they were not feminists, they were Marxists. However, women’s liberation is a project of Marxism, and Marxism is about the emancipation, or the liberation, of everyone, of all the oppressed.

I also think that, in the 1970s, the women’s movement as a whole was more left-wing than what we see today. A lot of the early issues were about really concrete demands that would change women’s lives, like childcare and abortion rights, and those of us that came after have benefited from all those things. But by the 1980s probably, that had already regressed, and the feminism that I came across was about the representation of women in media. It was about pornography. It was about ideas of women. Partly that was because some of the earlier demands had already been achieved, but it was also a kind of right-wing tilt, as the more radical days of the 1970s had slipped away, and society as a whole was moving to the right. We see that with the emphasis today on sexual violence, which is certainly a problem. But sexual violence is very much tied up with these economical points, with society as a whole.

As a young, white woman in an imperialist country, I did not feel particularly oppressed. I kind of knew I was one of the lucky ones. Then, I had a baby, and then another baby. And I began to notice a lot of things about the structures that exist even in our relatively privileged society—the way in which my partner and I were channeled into roles. As soon as you have a child, the whole structure of the family within capitalism starts to limit your choices. That is why I am not a feminist. I am a Marxist because we have to get rid of these structures, or we will not make gains—or any gains we do achieve, we will lose again.

JS: I would not assume that anybody in this room considers the SL relevant. It is worth discussing how it may have had good ideas, but I do not think it was everrevolutionary. On the question of not feeling oppressed, I think that is common among younger women. It is one reason that the women’s liberation movement, by and large, was not started within the student movement, but by slightly older women.

What are the political demands the socialist party in the 21st century would have to take up, acknowledging the changes of the 20th century? What are the most basic concerns of the socialist movement, now? What do we demand? Take #MeToo, for instance. What does #MeToo offer for women today—and how could Marxism take up #MeToo? Because #MeToo is a cultural discontent in the present, in the 21st century. What does it mean that it is happening now? Could that be taken up in a revolutionary way?

JS: That is a critical question, though I am not sure I have an answer. I do think ignoring #MeToo or saying it is a distraction will not get you anywhere. How do we move that forward and use it to illustrate, Where is this all coming from? As I mentioned before, internalizing that you are inferior is an important factor. That is part of what women’s liberation did that was different—people actually began to see how they behaved according to the stereotypes. Then you also have to see who actually has the power, and what the power is: You starve, or do not starve; you get a job, or do not get a job; and all these different ways we behave. Explaining that in terms of people’s lives is a very powerful part of women’s liberation. I do not like to use the word “Marxism,” but I know when I act that I am not a free agent, completely. I have a degree of agency. But there is a degree in which I am formed by everything around me.

SM: I would agree with a lot of that, actually. I am critical of the #MeToo phenomenon, but what we can do with it is ask where it is a question of power relations and where it is not. It is about agency. Are you in a position where it is going to determine your future? Are you in a position to fight back? And I do not think it is just for women’s rights or #MeToo, but different forms of oppression. If you are in a weaker situation in terms of power relations, you become stronger by fighting together. That is one reason why we should avoid creating a victim culture in which you are not allowed to say or do anything. Women do not need to be protected and wrapped up; women should be educated and empowered, and producing intelligent responses to these problems, from a position of strength. I think that that is something that the Left can work toward offering. The Left has come a long way from just treating women as funny-shaped workers.

RB: More than anything else, “Marxist feminism” has offered me quite a lot of confusion. Marxist feminists have been great campaigners for women’s rights, but in terms of theory, I do not think they give us anything different.

So what are the concrete concerns for women, today? Casual part-time work in very low paying industries. Unionizing, educating women, and drawing women in from their isolation. There are many ways that we can push to socialize domestic chores within a capitalist framework; free childcare is a major one.

Anything that comes up, we can potentially intersect as Marxists, and that is what we need to do. One of our jobs is to bring in the big picture, because that is what feminists and others do not do. The #MeToo campaign will probably be a passing thing. In years to come, people will not necessarily remember it. So how do we try and offer a coherent worldview that offers a way out? Individuals posting on social media might raise awareness for a few weeks, but it is not going to accomplish much more that that. We can raise awareness and consciousness in a much deeper way.

Even as we might try to address #MeToo as Marxists, part of the desire behind it seems to be about just getting rid of Trump and bringing back the Democrats. Or, perhaps, getting Oprah to be the next president….

Right, #MeToo is propaganda by the political leadership of the bourgeoisie, in response to Trump. So what do Marxists have to offer? Well, they can offer a critique. They can try to show what it is: The political leadership of bourgeois women instrumentalizing women’s sexual trauma for their own interests. I do not think Marxists should reconcile the irreconcilable and say, “We can just be part of #MeToo.” I think what we can do for women is say, “Look, these women are treating your sexuality as something to be protected, not enjoyed; they are tapping into your trauma to instrumentalize you, to get you to vote for this particular party.”

RB: There has been a real lack of commentary in that direction. It is hard to put your finger on it, but the more you look at it, there is this attempt to bring back a nice veneer for the Democratic Party. There was a real anti-Trump political agenda attached to #MeToo that has not really been talked about, and because he is such an easy enemy, it is easier to stomach a “lesser evil.”

JS: I did not think I would be defending #MeToo, but I do not think it is a conspiracy of the bourgeoisie. Moreover, I do not think conspiratorial thinking has much to do with Marxism. Things unfold a particular way, and then we explain them as if the ruling class had a committee meeting in Washington and planned it out, exactly as it happened. That’s not how things work.

What do you make of the New Left claim, which was shared by the feminists at the time, that the personal is political? There have been many changes in terms of norms and expectations, when it comes to personal relations. To what extent has that been liberatory, and to what extent has it traced new forms of oppression?

JS: I never really understood “The personal is political.” Sometimes it was used to talk about individuals’ behavior. Insofar as I saw it on the New Left, the slogan had an unpleasant aspect, to my mind. It seemed to go along with the practice of “self-criticism” in Stalinist and Maoist tendencies. This “self-criticism” ran like a red thread, as far as I know, through the whole Soviet period. People have told me about how they foolishly decided to defend Nicaragua, in defiance of the party line, on the Moscow State University campus in 1978. Afterward, they had to “do a self-criticism.” It is a horrible and demeaning thing to see. That was one direction people went with the idea that the personal is political.

RB: I agree with Judith, but there is a more positive understanding of “the personal is political.” There is the small and the big. I demand the highest consciousness from my comrades—a higher consciousness than what I demand from a random person. At the same time, we should all challenge sexism, regardless of where it comes from. However, if we only focus on the personal, it becomes depoliticized.

Ultimately, it is about power relations. Most sensible people can distinguish between these things. Sometimes things get messy; we need to listen to women, but we need to give everything due process as well. Again, I think that #MeToo has become something of a distraction. Or, at least, it misses out on the role of the state, the role of bosses, which is what we would bring up as Marxists.

This applies in the case of Julian Assange, as well. The point about Assange is that, whether he committed the alleged crimes or not, he was never going to get a fair trial, because he was the founder of WikiLeaks. He was being targeted because of that. He was going to be put into prison for the rest of his life without a fair trial. It does not take a Marxist to tell you that, either. There are plenty of feminists who recognized that for what it was. But a lot of the Left had major illusions in the State. It is a typical example where we can distinguish the analysis of a Marxist and a non-Marxist in terms of how the role of the state is understood. What was the state’s intention? How will it be carried out? Look at someone like Chelsea Manning. That is how people who challenge the state are treated, and we should not be under any illusions about that.

SM: Regarding the personal and the political, I would mention that organizations do have a responsibility to their membership. On the British left, look at the scandal with the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), regarding allegations that a party official committed sexual assault. You cannot have a “trial by mates” in such a situation.

I think you have all alluded to the benefits of the sexual revolution of the 1960s. Did that simply represent progress for women? Or does the sexual revolution have a more ambiguous character—particularly in light of recent history, up to and including #MeToo? Did the sexual revolution ever really happen? Has counterrevolution drawn back on the gains?

JS: I sometimes like to raise the idea that, because everybody is liberated, women are hit on more often, because they are obviously available. That’s a provocation. I do not think that the empirical evidence necessarily shows that. There has been more sexuality, though apparently that is now on the ebb. That might not be a bad thing, in some sense. Perhaps the hyper-sexuality of everyday life is a problem?—To be clear, I do think sexual liberation has been a plus for women, overall. On balance. But there is a downside to everything—right?

SM: Overall, there was definitely a net gain. We can look at very specific things, like the pill, for instance. But we must keep in mind the cultural level as well as the economic basis of society. When the struggle declines, alternatives to working class politics pop up. This happened in the 1970s, into the late 1970s and beyond. Initially, when women’s liberation was more radical, more revolutionary, it was tied up with revolutionary change in society in general. When that petered out, the more reactionary forms of feminism began to grow. So, it is partly about ebbing and flowing, and perhaps there has been a net gain—but what does that really mean? #MeToo is a reflection of our poor cultural level and the state we are in. Everyone is like, “How could Trump end up in the White House?” You need to look at the big picture. Things ebb and flow, but I do not think it is necessarily in a positive direction, in that sense.

Right now, it seems that we demand from the government programs, services, protections, and so on, especially for women and children. In the 1960s, the New Left was critical of the welfare state, which was seen as authoritarian. Later, in the 1970s and the 1980s, people from that same cohort became vocal defenders of it. What is the relation between the New Left and the welfare state? How does the struggle for women’s liberation figure into that?

SM: Things have different manifestations over time, but at the moment, a lot of the Left relates to the welfare state in a very reformist way. In part, this is a natural extension of the Left’s relationship to the Labor Party. Jeremy Corbyn is perhaps a sign that we are starting to wake up a little bit. But—this is what we think of as progress? It really shows the paucity of our cultural level and our consciousness. Corbyn is not really that left-wing, but he became this figure everyone is looking up to. This is a sign of how backwards everything has become. There is no alternative. There is no revolutionary alternative.| P

Transcribed by Tamas Vilaghy

Saturday Night Live, “Dinner Discussion,” YouTube video, 4:25, 27 Jan 2018, Season 43, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=evWiz6WRbCA.